Award received by author: 2011 Hudson Prize for Fiction; One of author’s occupations: programming director for the Bowery Poetry Club and Howl Arts; Number of poetry collections author has written: two; Non-literary publication in which author has published work: Mathematics Magazine; Representative sentence: “As I went, the city drew in close, the slate and marble streets merged with the overcast sky and the reflectionless windows and the mobs in their faded uniforms, but my focus remained on the spots of red, each mark maintaining its perfect round shape, glistening, and refusing to be absorbed into the ground.”

Imagine a trail of blood: bright crimson drops stretched to either side of you across a vast backdrop of gray (gray pavement, gray city, gray institutional life). At one end is a man—bleeding and stunned, walking hopelessly, unable to explain himself or speak. At the other end, where the trail began, lies an answer, perhaps; approach it, though, and the man recedes, becomes a point, and eventually, his face burned into your memory, a fiction to be tracked in your mind.

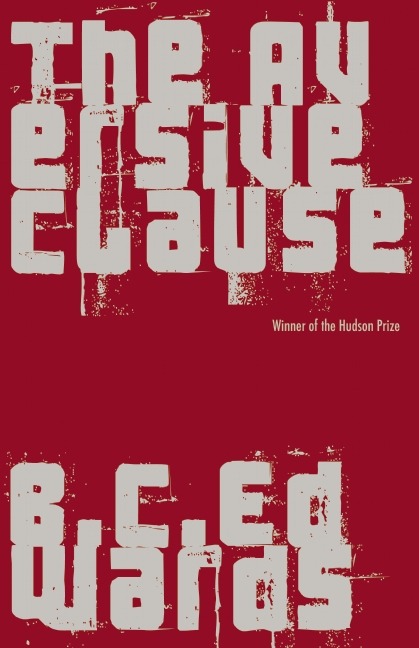

This is a bare-bones rundown of the eerie tale “Spots,” a scenario that perfectly captures the strange welding of the real and the fabricated in B. C. Edwards’ fine collection The Aversive Clause. The oblique and the imaginary are the author’s road to truth, while the purportedly real can seem, by turns, dream-filtered and insubstantial or emotionally dead. It’s through shifting, dubious vantage points that we catch wisps of being: the twinge of loss when everything is accounted for, say, or that peculiar sensation of standing outside of life, looking in.

“As I was walking down the street that afternoon I crossed paths with a man with blood pouring down his face,” the narrator begins. Losing the man in the crowd, he moves on, late for an urgent job interview. (The passersby, thoughts on their “obligations,” are silent.) It’s along the way, as he notes bloodspots trailing in the direction he’s headed, that the societal forces at work come to light for us: a looming police state and caste system, the narrator’s joblessness, his family’s dwindling tickets for rations. With his worn shoes, his “unironed and oil-stained” gray shirt, the narrator dangles perilously above his world’s lowest tier. And whether it’s the gloomy gray color scheme or the crowd’s inhuman silence, we quickly sense that this world is off-kilter, a place where apparitions might bob up like subconscious terrors, where bloodspots are the only objective evidence of the bleeder’s reality.

In the scene that follows, the narrative fabric grows more gossamer as a second story takes over. At the interviewer’s office, we meet the embodiment of brute authority: an official who smiles and laughs, all the while making it perfectly obvious he’ll break the narrator for the slightest misstep. Launching into a story—both to justify his lateness and distract the officer’s attention from his class—the narrator embellishes his encounter and journey. Describing himself offering aid to the bleeding man, a woman shouting for help, then the bloodspots he hounds down an alley, he keeps the interviewer entranced. All of life’s ingredients are present in this desperately mimetic fiction—everything the real world snuffed out. With its portrait of resolve, its hyperdetailing (as he walks farther, the spots’ edges grow firmer, “imperceptibly crusting over”), its evocation of lost fellow feeling, we can’t help but ask alongside the interviewer: “What happened then?”

In fact, for the official—caught in narrative’s spell, seemingly impressed by its power—the story is interesting only as long as it’s dramatic. He demands a perfect performance, one in which the narrator’s shabby mien and low class are offset by listener wonderment. The anecdote is a test of character—a fact of which the narrator is keenly aware, his voice “clear and unwavering” as he tries to remake himself, through the story, as a compassionate citizen and a stickler for detail. The only way to justify his lateness, apparently, is by constructing a seamless mask—one that imparts decisiveness, gusto, and blind submission. In other words, the narrator must tailor his story to his audience, reflecting its desires and values while keeping his flaws submerged.

Ironically for readers, though, it’s while proving himself through falsehood that his true skill and spirit shine through. Allowed inside his mind, we catch his story’s subtleties. Once he begins his apology (after recalling, internally, “the desperate look which peered back at me from the mirror most mornings”), his cool demeanor jars against our sense of him—yet, knowing his motive for lying, we root for him in his artifice. Seeing beneath the mask, we intuit the truths in his story; key details, such as the spots and his threadbare shoes, morph and repeat so often they come to feel emblematic, stand-ins for his adversity. Such objects pile up lies on one level, peel them away on another. For the interviewer they bolster the illusion of the story, while for us they heighten suspense by widening the gulf between surface and subtext, assertive mask and inner unraveling. But eventually the gulf drops away: the narrator seems gripped by his tale, closing in on the wounded man’s mental state, voicing their shared psychic pain. And as he reflects the world through the bleeder’s eyes, his own place in it comes into cruel, vivid focus.

Struggling against roles and masks, many of the characters in The Aversive Clause seem locked in their own private realms—talking through hissing, watery-voiced phone lines, experiencing life in parallel dreams or media. Masks held in place, imagination becomes a bridge between subjective territories, a means to uncover what’s been lost. What the teller in “Spots” finds at the end of the trail triggers an event that’s also an indictment—of a society that condones masks and labels, injustice, routine alienation. Fiction is the daily reality that these characters navigate, but the ending suggests that for those who won’t or can’t renounce their human failings, the truth, eventually, will out.

In the way of good fantasy then, Edwards’ stories—like Magritte’s canvas opening out on cloud-daubed blue—access the supercharged Real. His narratives are self-contained, insisting on their own weird realities, while feeding off the ailments of our own. Death-happy newsmen, love-racked zombies, doppelgängers hired by advertisers to draw a crowd’s attention—once fleshed out, such far-out premises are imbued with a sad humanity. Like a trail of blood, each wrests us away from ourselves toward the inner life of another. And even when that mystery seems unknowable, we continue to be led by its pull.