Alexandros of Antioch, Venus de Milo, 150-125 BCE

We’re pleased to present a series of excerpts from Jane Ursula Harris’ forthcoming book, After: The Role of the Copy in Modern and Contemporary Art. Harris’ survey assembles key examples of the copy from the onset of modernism to the present, and explores the copy’s relationship to the western canon. The following is the first of a two part exploration on the history and influence of the Venus de Milo.

See Part II, and On Jasper Johns.

On Venus de Milo (Part I)

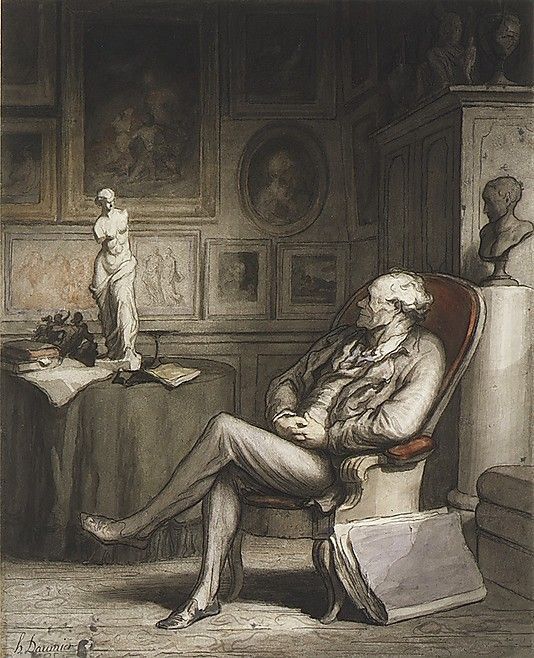

The story of the Venus de Milo’s acquisition and provenance is essential to her stardom, and art-historically speaking, she is a star. From Honoré Daumier and Salvador Dali to Niki de Saint Phalle and Andres Serrano, countless artists have paid homage to the ancient work.

But the Venus de Milo didn’t always seem destined for fame. For ages she lay in a heap of ruins on the island of Milos, and might have languished there forever if a local farmer hadn’t discovered her in 1820. He hid his find from the Turks who ruled Milos at the time, but authorities found him out, and seized the broken statue. This too could have been the end of her story, had Comte de Marcellus (1795-1865), secretary to the French embassy in Constantinople, not intervened, immediately understanding the value of such a monumental work.

Five years earlier, in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat and exile, France had been forced to cede the celebrated Medici Venus and Apollo Belvedere back to the Vatican. Marcellus knew his monarch would be eager to acquire the work, as a result, and soon arranged for the purchase of the Venus de Milo. He presented the larger-than-life statue, relatively intact for an ancient work of art, to Louis XVIII the following year. It sold for 1,000 francs (about $20,000) , together with the plinth it stood on, and fragments of its missing left arm.

In addition to France’s desire to rebuild its treasure trove of antiquities, the Neoclassical period (1770-1820) that was still flourishing at the time helped motivate the acquisition. For in a pivotal, perhaps willful mistake, the statue was immediately presumed to be an authentic classical work, and installed in the classical wing of the Louvre.

The misattribution remains key to the legacy of the Venus de Milo. Had her true author been known, she likely would’ve been locked away in the museum’s archive, if not sold off. Hellenistic art had by then been denigrated by Renaissance scholars who re-conceived it in anti-classical terms, finding in its expressive, experimental form, and emotional content a provocative realism that defied everything their era stood for: modesty, intellect, and equanimity.

It helped that the Venus de Milo possessed several classical attributes. Her strong profile, short upper lip, and smooth features, for example, were in keeping with Classical figural conventions, as was the continuous line connecting her nose and forehead. The partially-draped figure with its attenuated silhouette – which the Regency fashion of the day imitated with its empire bust-line – also recalled classical sculptures of Aphrodite, and her Roman counterpart, Venus. Yet despite all these classical identifiers, the Venus de Milo flaunted a definitive Hellenistic influence in her provocatively low-slung drapery, high waist line, and curve-enhancing contrapposto—far more sensual and exaggerated than classical ideals allowed.

Praxiletes, Aphrodite of Cnidus, 360-330 BCE.

By the late 19th century speculations about the statue’s original pose, including what the Venus might have held—a shield, an apple, a spindle, a mirror—or been enacting, were rampant. The mystery captivated many at a time when nascent archeological studies ushered in a romantic fascination with ruins. As a ruin itself, the Venus de Milo embodied this fascination, functioning as a paradoxical symbol of disfigurement and beauty. The concurrent obsession with Greek mythology enhanced the desire to determine the work’s true nature, but efforts to reconstruct its gestures and limbs were resisted, and the puzzle remained.

Honoré Daumier, L’amateur. Pen and ink, wash, watercolor, lithographic crayon, and gouache over black chalk on wove paper, 17 ¼ x 14 in. (43.8 x 35.5cm), ca. 1860-65.

The resulting ambiguity led some classical historians to repress the Venus de Milo’s carnal appeal, undercutting the work’s sensuality with intellectual claims. Historian L. R. Darnel, for example, proclaimed in 1896 that she was “free from human weakness or passion…with an earnestness lofty and self-contained, almost cold” , and Rodin called her “voluptuousness regulated by restraint.”

Such purifying tendencies also had their abject counterparts. As Helen King, professor of Classics at the University of Reading suggests: “It is significant that Leopold von Sacher-Masoch chose to call his novel celebrating masochism, Venus im Pelz (Venus in Furs, 1870), while in 1884, under the pseudonym ‘Rachilde’, Marguerite Eymery, who sometimes dressed as a man, published her Monsieur Venus, the story of a woman who uses the parts of her dead lover to create a male Venus.”

Rachilde, like Sacher-Masoch, represented the fin de siecle movement of Symbolism, which thrived on dark, heretical interpretations of classical and biblical themes. Her proto-feminist twist on the Pygmalion myth exemplified the Symbolist approach, if through a uniquely female perspective.

Symbolists were hostile to modern bourgeois culture, and the materialism and naturalism that dominated the arts (Realism, and Impressionism, namely). They aimed to “depict not the thing but the effect it produces”, and as Jean Moréas declared in his manifesto in Le Figaro, their enemies were “plain meanings, declamations, false sentimentality and matter-of-fact description”. To this end, eccentric visions and provocative fantasies reimagined mythological subjects through a subjective lens.

The emergence of psychoanalysis and the theories of J. M. Charcot, greatly impacted the Symbolists. Charcot’s exploration of myth, dreams, and the language of the unconscious not only justified their escapist flights of fancy, but shaped their desire to suggest meaning beyond form. The emphasis on the morbid, perverse, erotic, and melancholy also helped engender its penchant for altered states of perception, evidenced in its attraction to the occult.

Charcot’s theory of hysteria, which, by equating women with pathological impulses, helped pit notions of the eternal feminine (woman as virtue) against those of the femme fatale (woman as unbridled desire), must have influenced the Symbolists’ relation to the Venus de Milo. For in this goddess of love, whose hybrid style conjoined two competing value systems—the rationality of classicism, and the sensuality of Hellenism—fin-de-siècle artists found a symbol of conflict onto which they could project the anxieties and tensions of their age. Hence, Sacher-Masoch imagines her as a “beautiful despot”, a mistress who whips her mortal lover to ensure his devotion, thus transforming herself from a paragon of beauty into the femme fatale. Both of them are defiled by their union yet born anew by the pleasure it subtends, signifying the uneasy, if inextricable, relationship between modernism and female sexuality that would become one of its defining themes. “Drawings of the Venus and a wide range of interpretations from a spectrum of nineteenth-century artists within a few decades of the statue’s discovery point not only to the continuing fascination for the antique in the modern world, but also for the female figure, characteristic of the late nineteenth-century vanguard of art.”

Nowhere is this defining relationship between modernism and female sexuality more evident than in the work of Surrealists who, indebted to the Symbolists, similarly fetishized the Venus de Milo in psychosexual terms. Through their fantastical projections, and conflations of the feminine with the unconscious (and the “marvelous” revelations it contained), the canonical work exemplified the essence of the uncanny; the dissolution of the real.

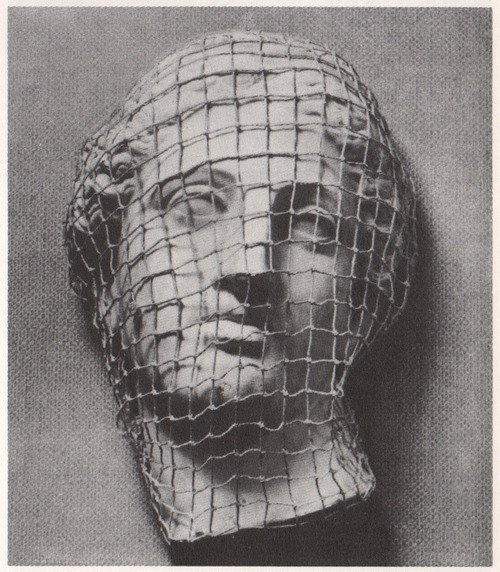

Man Ray, Venus Restored (head), 1937.

In his seminal study, Greek Mythologies: Antiquity and Surrealism, 2012, Dimitrios Yatromanolakis theorizes that archaeological discoveries of ancient Greece in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries helped shape this perception, and the Surrealist enterprise in general.

Yatromanolakis’ view implies that the Venus de Milo’s appeal as classical muse, mythological subject, and hybrid form, must be taken together with its evocation of ruins (both aesthetic and ideological). Certainly her broken, ruinous state echoed the wartime traumas and economic upheavals Surrealists witnessed in the 1920s-1940s. Their rebuke of the rational, like the Dadaists before them, was forged from these experiences and observations. The movement’s celebration of dreams, madness, and ecstasy was a form of insurrection, accordingly.

Yet for its largely male practitioners, the Venus de Milo was ultimately reduced to: “a ready-made surrealist woman: pre-amputated and designed for pleasure, [she was] literally a dream come true.” This notion of a surrogate female engineered by (male) desire recalls the Surrealist fascination with female automata, and its real-world proxy; the mannequin. The latter too was heralded for its ability to elicit the uncanny, and the revelations of the “marvelous”. André Breton’s Manifesto of 1924 connects it as such to ruins: “The marvelous is not the same in every period of history: it partakes in some obscure way of a sort of general revelation only the fragments of which come down to us: they are the romantic ruins, the modern mannequin, or any other symbol capable of affecting the human sensibility for a period of time.”

The mannequin was a ubiquitous symbol of 1920s consumer culture, and a modern benchmark of beauty akin to the Venus de Milo, against whom the proportions of real women were often measured. As a mass produced feminine ideal, she was easily modified to Surrealist aims. The famous 1938 “International Exhibition of Surrealism” showcased several examples, with department store mannequins fantastically reconfigured by Man Ray, Jean Arp, Andre Masson, and Salvador Dali, among others. Most conjured a sense of defilement and restraint in their use of fishnet, bird cages, masks, and collars to bind, gag, and blind them. Mostly nude, each was positioned at a fictitious street corner in an installation that alluded to the dark alleys and avenues of Paris like rue Saint-Martin where prostitutes roamed.

René Magritte did not participate, but he was the first Surrealist to adopt the Venus de Milo in his work. The statue appears in his painting, The Flying Statue, 1927, standing amidst a cluster of architectural elements writ large, her right side and back pressed against by empty frames. A extension of paintings like The Birth of the Idol, 1926, and Lights, 1926, which featured mannequin-like parts, it treated the female body as fragment, and built affinities between animate and inanimate forms.

Rene Magritte, The Flying Statue (La statue volante), 1927.

Not long after, Magritte appropriated the Venus de Milo as a readymade when he altered a plaster tourist copy whose miniature form reduced the classical masterpiece to a domestic tchotchke. The resulting work, The Copper Handcuffs, 1931, created a frisson between her paradigmatic beauty as a classical ideal, and her broken, mutilated state. Magritte achieved this by painting sections of the statue in a Renaissance palette while abstractly delineating its form. The head was painted white; the torso in a coppery flesh tone (copper being the metal that traditionally corresponds to Venus); and the drapery in a midnight blue that merges with the black painted base at the back.

The most significant alteration, however, lay in Magritte’s painting of the arm stumps in black to suggest recent amputation. Recalling the abject, double-jointed dolls of Hans Bellmer, also produced in the mid-1930s, The Copper Handcuffs evinces a similar, if more subtle sense of violation by recasting the statue’s damage as pain.

Magritte went on to paint three additional versions (1931-1936), and in a 1936 letter to Breton, he compared the work to concurrent sculptures he’d been working on: “This object is reminiscent of the masks on which I painted the sky or a forest,” he wrote, referring to his use of cheap plaster cast masks, specifically the death masks of Napoleon and Pascal, once ubiquitously mass-produced as well.

As a Surrealist less swayed by the power of dreams and the unconscious, Magritte sought to expose the mysteries of the ordinary, observable world instead, creating poetic associations between the expected and strange. The artist’s transformations of the death masks and goddess statues not only subverted popular conflations of the classical with the kitsch, but gave them what he called “an unexpected life”. When Magritte decided to realize a bronze sculpture series of The Copper Handcuffs (1967), the same year he died, he encapsulated this intent as an effort to “restore to what is known that which is absolutely unknown and unknowable.”

Rene Magritte, The Copper Handcuffs, 1931.

Man Ray was another Surrealist who made use of the ubiquitous plaster reproductions of the Venus de Milo found throughout Paris. In Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age, 2003, Julie Wosk argues his relationship to the iconic statue was shaped by Pymaglion-esque fantasies of the erotic female sculpture come to life, which his Rayogramme, Electricite, 1931, anticipates. Electricite depicts two overlaid photographs of his lover Lee Miller’s headless and armless nude torso, one seeming to emerge from the other. A series of diagonal wavy lines evocative of electrical currents bisect the frame, and animate the action. According to Wosk, Man Ray’s fascination with “fragmented and disembodied female figures may have been fed by [Lee] Miller’s appearance in Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet [1930], in which casts of classical sculpture, including the Venus de Milo, seemed alive and had the heads of living persons. During the 1930s, Man Ray continued to produce photographs of stone female figures coupled with living models.”

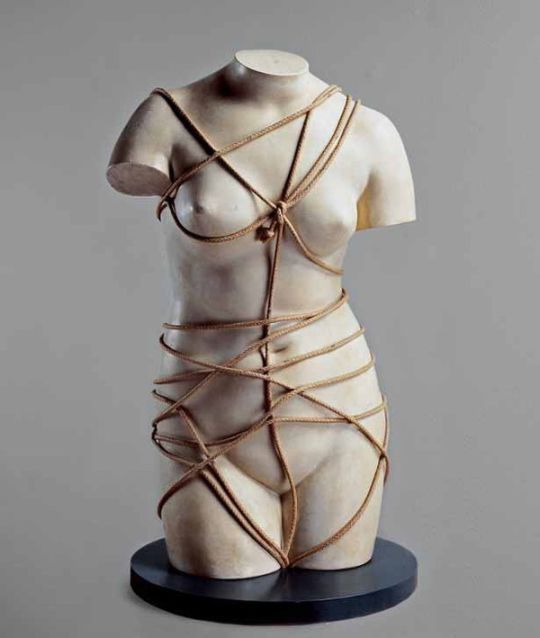

The latter, a photomontage series created between 1931 and 1936, irreverently poked fun at the so-called paragon of classical beauty, but as with Magritte, Man Ray’s most poignant appropriation was a provocatively altered readymade, Venus Restored, 1936. The aptly titled work undercut the culture’s fetish-like reverence for antiquity in addition to courting Pygmalion fantasies. Lopping off the head and legs of a plaster copy, and tying the mutilated figure with heavy rope, Man Ray served her up like a masochistic offering to the masses. Man Ray’s desire to undermine her status as romantic ruin sought to liberate the Venus from the repressive sexual norms that circumscribed her reception.

Man Ray, Venus Restored, 1936.

More than any other Surrealist, however, it was Salvador Dali who would rescue the Venus de Milo from potential obscurity, the infamous eccentric returning again and again to her provocative image for over thirty years. Her “stupid expression,” he argued, made her “the quintessential beauty”, and like his beloved wife Gala, she became a lifelong muse. That the artist’s first sculpture was a terra-cotta copy of the Venus de Milo attests to this preoccupation, its creation, according to Dali, engendering “an unknown and delicious erotic joy.”

Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936, is Dali’s earliest, and most renowned example. It features a half-size plaster copy that, in a play on the woman-as-vessel trope, turns her into a literal chest of drawers. After painting the plaster white to mimic the surface of marble, and marking the places where he wanted the drawers to be, Dali paid a cabinetmaker recommended by Marcel Duchamp to construct the work. Six apertures were cut into the goddess’s forehead, breasts, abdomen, and bent left knee, each outfitted with a half-open moveable drawer and a knob covered in white mink fur.

Salvador Dali, Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936.

The body-as-cabinet metaphor materialized in the work’s uncanny juxtapositions of hard and soft, open and closed, embodied the unconscious as that which reveals and conceals our deepest desires. To this effect, the half-open doors lure viewers to penetrate their shadows and their silky knobs beg to be caressed. Transposing art’s traditional mandate to “look but don’t touch” into such sexual terms, Dali taunts us with the appeal of the forbidden.

Though the work was made on the eve of the Spanish Civil War, after the assassination of his friend, the poet Federico Garcia Lorca, its allusions to the impermanence of flesh, and the irrationality of order, were described by Dali in apolitical terms: “The only difference between the immortal Greece and contemporary times is Sigmund Freud, who discovered that the human body, purely platonic at the Greek epoch, nowadays is full of secret drawers that only [the] psychoanalysis is capable to open.”

Dali’s painting, Le Cabinet anthropomorphique, 1936, and his drawing, The City of Drawers, 1936, made at the same time, also depicted the Venus de Milo as a cabinet with drawers, her figure however made much more muscular and voluptuous. In both, her head is bowed so that her long hair cascades down into the top drawer. What is obscured tantalizes. The artist’s contribution to the 1939 World’s Fair, the Dream of Venus Pavilion, expanded upon the cabinet reference, inviting viewers to experience the Goddess of love’s dreams and enter her mind in an installation “filled with nude women, mermaids, melting clocks, and underwater dreamscapes.”

Salvador Dali, The Anthropomorphic Cabinet, 1936.

As with Man Ray, Dali underwent the production of a bronze edition of his 1936 sculpture in the early 1960s, a series cast with eight moveable drawers, and rendered in a green and black patina. It was not fully realized until 1988. By then, Dali had left Surrealism behind, long at odds with the movement’s politics, and bored with its mandates. His attention had instead turned toward his interests in science and religion, which drew heavily on Renaissance precedents. His renewed passion for the Venus de Milo within that context produced many variations over the next 25 years, including a 1973 hologram portrait of the musician Alice Cooper, where the iconic statue forms a microphone.

One late example from 1988 depicts a watery blue Venus cast from glass paste with five knob-less silver drawers. In this 17-inch version, Dali achieves a material discord akin to his 1936 original, juxtaposing shiny, cold metal with a liquid translucence. In addition to the soft-hard dialectic, a quintessential Dali motif, the late Venus works also manifest the artist’s interest in the idea of displacement, literal and psychological, which he often explored through humor and sex. In the painted plaster bust, Otorhinological [sic] Head of Venus, 1964, for example, Dali switched the goddess’s nose with her ear, the former projecting from her serene face like a bad sexual pun (the ear in Freudian symbolism was associated with female genitalia, and fertilization in general).

In what is perhaps Dali’s most complicated engagement with the canonical work, The Hallucinogenic Toreador, 1969-70, the Venus becomes a spectacle of self-replication, evoking female automata. Moving in a gentle arc from the left side of the monumental painting to the right, each iteration appears to grow larger and sharper as it moves forward in pictorial space. Enclosed at the top by a de Chirico-esque arcade, the assembly-line emerges from the dream-like haze of a painted white scrim into the saturated light of full consciousness, suggesting revelation and realization simultaneously.

The two largest Venus figures in the foreground create an image of a bullfighter between them; the left breast of one articulates his nose, her abdomen his chin, and the skirt of the other Venus evokes a red cape, etc. The double image supposedly first appeared to Dali when he bought a box of coloring pencils that featured the image of the Venus de Milo on the box, and he saw in it a face.

The optical illusion of the toreador, symbol of death and glorified violence, like the vanquished bull in the lower left quadrant, lying in a pool of its blood, provides a marked contrast to the graceful visage of the classical Venus. Images of Dali as a child in a sailor’s suit, the bust of Voltaire, life-sized flies, the peasant woman from Jean-François Millet’s The Angelus (1859), and a portrait of his beloved Gala, who looks down disapprovingly at the young Dali from the top of the arcade, add to the iconographic discord, as do the exploding molecules that delineate the toreador’s right shoulder.

For some scholars, the dizzying amalgam can be understood in psychoanalytic terms, as “representations of extreme, complementary fantasies: the phallic, devouring mother in the presence of the sacrificial gorged bull or the stunned child, and, in the same pictorial or psychic space, numerous references to [this mother’s] ‘castration.’” Such an analysis implies both Gala and the Venus as the mother figure, and encourages biographical interpretations that lead to speculation: Does the toreador represent the artist, childhood memories, the role of fate, his love for Gala, the battle between civility and instinct, or all of the above?

The enigmatic, disconcerting affect of the complex composition is intentional, and reflects Dali’s application of his infamous paranoid-critical technique, which he defined as a “spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena.”

Dali’s simulation of paranoia sought to destabilize reality and identity alike, his use of optical illusions, and illogical juxtapositions enacting what he believed to be the universal language of the subconscious: “The subconscious has a symbolic language that is truly a universal language,” he said, “for it speaks with the vocabulary of the great vital constants, sexual instinct, feeling of death, physical notion of the enigma of space—these vital constants are universally echoed in every human. To understand an aesthetic picture, training in the appreciation is necessary, cultural and intellectual preparation. For Surrealism the only requisite is a receptive and intuitive human being.” While that universal language may affirm little more than our own apprehensive projections, the painting’s reproduction of the Venus de Milo within the threatening atmosphere of a bullring, and her conflation with a toreador, certainly conveys the power of the unconscious to destroy expectations, and liberate fantasy.