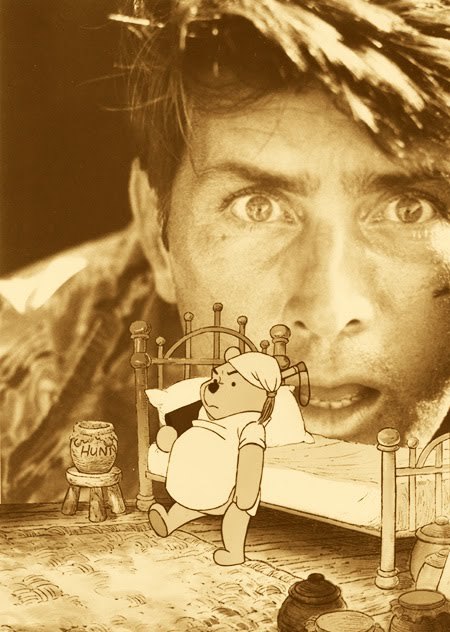

Todd Graham grew up in the small town of Peterborough, Ontario in the 1970s, where he spent his formative years warping his mind with MAD, National Lampoon, and Heavy Metal magazines. In 1987, while a film student at Ontario College of Art and Design, Graham faced a fast-approaching deadline for a class project. He had to produce a short film, and quick, so ran with a goofy whim. Inspired by an off-the-cuff joke involving a stuffed Tigger doll, he laid some clips from the Apocalypse Now soundtrack over scenes from Disney’s Winnie the Pooh and vice-versa.

The resulting short, Apocalypse Pooh, was akin to watching The Wizard of Oz while listening to Dark Side of the Moon, but funnier. A number of people in the latter half of the 20th century—the Situationists, bands like The Residents and Negativland, and filmmaker Craig Baldwin among others—had manipulated existing images and soundtracks as a means of cultural critique long before Graham, but his film was somehow different. Apocalypse Pooh was strangely and accidentally profound. By blending two seemingly incongruous preexisting sources, Graham made something completely new, if only because the two sources worked together so frighteningly and unexpectedly well. After the film was shown to his class, friends began requesting it at underground Ontario screenings. Bootleg copies started to make the rounds internationally among collectors of strange films. Apocalypse Pooh was included in a number of traveling animation festivals, began popping up on VHS anthologies of weird shorts, and was analyzed in serious film journals.

As Apocalypse Pooh quietly wormed its way through underground culture, Graham, unaware that all this was happening, continued making similar experimental films in which he combined Peanuts cartoons and Blue Velvet, and Babar and The Elephant Man. The unfortunate thing is, justifiably fearing a letter from Disney’s legal department concerning certain copyright issues, Graham left his name off Apocalypse Pooh, and so was never recognized as the film’s director until much later. At least that’s how the legend goes.

“This is a popular misconception,” says Graham, now 50 and living in Toronto. “I did have a title card with my name—T. Graham—on the original tape, as well as the original title of the piece which was Homeformat as I was mimicking the structure of a commercial VHS release of the day. It’s correct that Disney’s legal team was at its most tenacious during this time. They were suing nursery schools for painting unlicensed murals until someone pointed out that it was, more importantly, brainwashing future consume-eteers. I heard third-hand that somebody who worked at Disney Canada brought [Apocalypse Pooh] in to their office back in the day but they felt it was obscure enough not to worry about.”

“Anybody who wanted to track me down could,” he further clarified. “Especially once the internet coagulated. I got a very surprising phone call in 1999 from the Whitney Museum looking to include Apocalypse Pooh and Blue Peanuts in a millennial retrospective of film and video. It was only anonymous on some traded tapes and compilations that chopped off the beginning. When it appeared first on iFilm and then YouTube in 2006, I contacted the people who posted it and asked them to attach my name and contact info.”

In the later 80s and early 90s Graham moved on to live action shorts, though most still included cartoon elements. Good Grief Cancer Boy! (1990), for instance, the first of a planned trilogy of foreign film parodies, has been described as “a post reunification Nihilist allegory of the tensions between the immigrant worker population of Germany and the natives who still long for Heimat. When foreign bullies cajole a young German man into trying to kick an American football. Hilarity ensues.”

“Each was to be created as though they came out of a distinct foreign film culture,” graham says of the trilogy. “The idea was (and it still holds true today) that Canadians only prize art from outside of Canada, so I would trick them into embracing my work. The first film was mimicking the New German Cinema, particularly of Herzog and Fassbinder. ‘Good Grief! Krebsjunge! was shot on 16mm in 1990 but it would have been expensive and arduous to finish with sub-titles etc., so I didn’t end up finishing it until twenty years later. It’s basically Charlie Brown as Nietzsche’s Übermensch.”

“The second film was shot in Super 8 and aligned with the style of the French New Wave by way of Jerry Lewis’s infamously unreleased The Day The Clown Cried. It’s called The Happy Clown of Death (Le Clown Joyeux de la Mort) and was going to be silent with a classical soundtrack. But it’s too boring, so I have been working on adding in a fake DVD commentary that will have a supplementary storyline. The final film of the trilogy will be a POV digital short called Office Dog, but I still haven’t shot it yet. It’s going to be kind of an Asian action pastiche. Part John Woo, part Takashi Miike, but from the perspective of a put-upon dog who works in an office. I do intend to finish these.”

About ten years ago, after what he describes as “a kind of positive midlife crisis,” Graham, who has a wife, a family, and a good job, decided to try his hand at becoming a stand-up comic.

“I was always a big fan of stand-up, even from grade school in the 70s, especially Steve Martin, who inspired my meta-performance in Grade 7 where I did a presentation on the history of comedy, complete with live rim shots. It went over pretty well, but didn’t win over any of my tormenters. Contrary to the old comedian origins trope about winning over bullies with laughs. I did a couple stand-up sets at school assemblies as a senior and then drunkenly tried to recycle the same dumb jokes at a super PC art school cabaret which cemented the idea that I should just make films where I could distance myself if necessary. I’d make drunken threats to do stand-up for the next decade or so but didn’t actually do anything about it.”

After taking a couple comedy classes at a local community college, Graham finally started working the clubs, and over the past eight years or so has become an increasingly familiar presence on the Canadian comedy scene.

Graham delivers his jokes in an uncomfortable straight-faced stammer punctuated by silent pauses that can go on, well, let’s just say for politeness sake “way too long.” But it’s those pauses that make it work, having the effect of not only making the eventual punchlines that much more unexpected, but even making the set-ups themselves much funnier than they might normally be. (“So I picked up a Hitler album the other day…”)

“It evolved like anything,” Graham says of his delivery. “I used to frantically pace back and forth, barely acknowledging the audience. A comic I admired, the hilarious Mark Forward, told me to cut it out and just stand there. I tried that and then slowed down my delivery to accommodate my natural stammer. I think it needs to be fairly authentic or you would be Larry The Cable Guy, a hollow cartoon… stuffed with money. “

Even as he receives more widespread recognition as a comedian, that first short keeps following him around.

Almost three decades after it was first pieced together as a class project, Graham’s Apocalypse Pooh has since gone on to be considered not just a classic, but recognized as the first widely distributed modern example of a mashup. It would be an inspiration to countless artists, musicians and culture jammers down the line, many of whom would make a great deal of money off his idea, and many of whom likely wouldn’t know what a VHS tape was if it was handed to them. Take a look online and it can seem like combining preexisting music and video to create something new and ironic has become the dominant creative outlet of the 21st century. Graham, for his part, remains fairly philosophical about his role as the man who started it all.

“The mashup approach has always appealed to me because it’s how I think. It’s just how my brain is wired, which some consider a talent and some call a learning disability. I’m just getting to reading the Malcolm Gladwell book The Outliers, and find it pretty interesting—especially about recognizing opportunity. For instance, I wasn’t savvy enough to post Apocalypse Pooh on YouTube myself. It was a stranger who did it. But back in analog days I worked in the mail room which gave me the ability to send copies of it out to lots of art galleries and magazines. I never heard back from many places, but found out years later that it had spread around a fair bit. Any influence it may have had came out of that.”