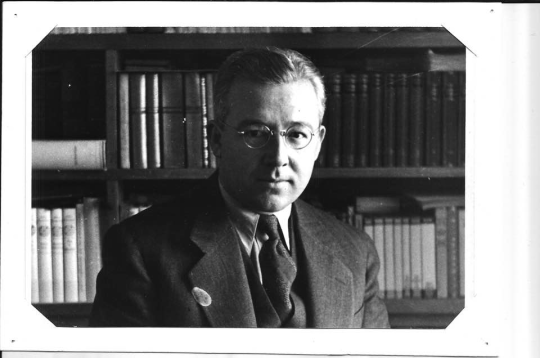

A self-portrait by Sabahattin Ali.

Kaya Genç on Sabahattin Ali’s Madonna in a Fur Coat

In 1938, at the height of Turkey’s single-party rule, three of the country’s four great writers were in jail. Two of them, the poet Nazım Hikmet and the novelist Orhan Kemal shared the same cell at Bursa Prison. They wrote poems and stories, translated and reviewed fellow authors’ works, and engaged in lengthy correspondence with the novelist Kemal Tahir, who was serving a fifteen-year sentence in another prison in Anatolia. They all agreed on the brilliance of the writings of their fellow author Sabahattin Ali, a thirty-one-year-old novelist and short story writer, who had done time at Sinop Fortress Prison (where most communist sympathizers were locked up) in the early 1930s. Ali had been imprisoned after lampooning several leading republicans in a poem he recited to a group of friends. After his release in 1933, Ali was forced to compose a poem full of praise for the same figures, so as to be allowed to teach at a state school in Konya, the Anatolian city where Rumi composed Mathnawi in the thirteenth century.

Hikmet considered Sabahattin Ali the leading Turkish fiction writer of the age. His first novel, Yusuf from Kuyucak, ridiculed the statist argument that there were no classes in the young Turkish republic; Ali saw signs of a class society everywhere, however passionately Turkey’s rulers denied its existence. Ali’s 1943 novel, Madonna in a Fur Coat, recently published in English for the first time by Penguin Classics, is also about noticing these things in New Turkey.

Madonna in a Fur Coat tells a story with a frame that some find even more interesting than the actual story. The main story follows a young, fragile Turkish man’s love for a charismatic German artist. The narrator of the frame story, meanwhile, is an unnamed twenty-five-old banker. The narrator is introduced to us after he loses his modest post in a bank (“I am still not sure why, they said it was to reduce costs”). Like Sabahattin Ali, he is a dreamy young man in love with books and is considered a failure by people whose cruelties towards the less fortunate he never fails to see.

Early in the book, as the narrator wanders among different ministries and companies in New Turkey’s capital, Ankara, to look for work, he sees numerous episodes of class division. While watching workers march alongside the façade of the People’s House, an official building of the republican regime, the narrator comes across an old classmate, Hamdi, now a successful businessman, who invites him to his house. With a few masterly brush strokes, Ali draws a portrait of New Turkey’s model middle-class family: modern, childless, efficient, and condescending. The middle-class life comes alive as he describes his friend’s home: “On the wall were photographs of relatives and film stars; on the bookshelf that clearly belonged to the wife, there sat a number of cheap novels and fashion magazines.” Hamdi offers our narrator a job, and the book transitions to the main narrative, beginning sometime after the narrator starts work at Hamdi’s firm.

Sabahattin Ali (2nd from right) in Berlin with a group of fellow Turkish students

In a letter to Ali dated May 1943, Hikmet confessed to have “both loved and resented” the novel. He found fault with Madonna’s frame narrative technique and disliked the main story. But Hikmet loved this section. “The first part of the novel is excellent,” he wrote. “The development of this part, its analysis of the true face of a little bourgeois family, could expand further and so one can’t help but say: while moving from this first part to the second, this very original, perfect introduction and the opportunities it provides, have been wasted… While reading it, by which I mean the sections before the Berlin part, I marveled at your realism.”

The second part of the novel focuses on Raif Efendi, the German translator at Hamdi’s firm, who shares an office with the narrator. Raif is an older, quiet man, and Hamdi interprets his reluctant demeanor as a sign of weakness. A comradeship is born between the shy narrator and the shy interpreter, both oppressed by the conventions of middle-class life.

Raif Efendi lives in a large two-story house with his extended family, who constantly exploit him to satisfy their endless commercial thirst. Through Raif, we get a nightmarish presentation of modern Turkey’s new, soulless generation. He also is constantly sick from work, with a common cold. “Now and again, Raif Efendi would fall ill and absent himself from the office,” the narrator notes, shortly after introducing him to us. But in the following weeks, Raif develops a fatal case of pneumonia. One day in February he does not show up at the office and the narrator learns that the sickly interpreter is taken to his home: he runs a fever and also complains of a stomach ache. There, our narrator comforts him. The night before his death, Raif Efendi allows him to read his accounts of his adventures in his twenties, when he lived in Berlin.

Sabahattin Ali went to Berlin in 1928, after winning a scholarship offered by the Turkish government. He spent two years there, fell in love with an artist, and after his return told friends that he could never forget her. Raif Efendi’s youthful years strongly resemble Ali’s: Raif Efendi is a confused young man who doesn’t know quite what he wants from life. He is twenty-three, confused about how he should spend the rest of his twenties. He seems alienated from society around him: his father, who is disappointed that Raif spends his youth daydreaming and reading novels, tells him: “Honestly, you should have been born a girl!” Young Raif’s greatest pleasure in life is to sit alone beside the river and let his thoughts “waft away”; he tries to be a writer but is scared to express what he refers to as his “true self”: “No matter what I had bottled up inside me, I was absurdly anxious about letting it out, and so my adventures in writing ended.” He starts painting, studying at Istanbul’s Academy of Fine Arts, believing that painting involved “no risk of revealing anything personal.” But he becomes paranoid. If his works “exposed any personal particularity” he goes to extreme lengths to hide it. When his friends or teachers recognize him in the works, he gasps: “like a naked woman caught in an intimate moment, [I] rush away blushing.”

Unlike the narrator, Raif constantly overlooks things. He’s modest, too shy to pursue his desires; because of his reluctance, Raif risks not finding what he wants from life at all—his dreaminess is how he resists engaging with the world. Ultimately, however, it’s his weaknesses that make him such a fragile and sympathetic character. He’s given a chance to explore his identity when his father sends him off to Berlin, where Raif is expected to learn about the soap business (“scented soaps in particular”). Europe has long been the home of Raif Efendi’s fondest childhood dreams; he has grown up reading books by Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, and Michel Zevaco. He spends the year taking German lessons three times a week, frequenting museums, and reading the Russians in translation. Convinced that the German soap makers see no ambition in him (“they…did not wish to waste their time”), he stops going to the factory altogether.

Berlin turns out to be a disappointment. “In the end, this was just another city. The streets were a bit wider, and much cleaner, and the inhabitants were blonder… I had yet to learn that nothing in this world can ever match the marvels that we conjure up in our own minds.” His favorite Berlin place is the Nationalgalerie, where he comes across a striking painting: Selbstportrat by the twenty-five-year-old Maria Puder. The young artist had painted herself in the manner of Andrea del Sarto’s Mother Mary in Madonna delle Arpie. Her “strange, formidable, haughty and almost wide expression” is striking to Raif, and he’s magnetically drawn to “this pale face, this dark brown hair, this dark brow, these dark eyes that spoke of eternal anguish and resolve.” She echoes all the women that had fascinated Raif in books; he sees the protagonists of Turkish classics as well as Cleopatra and “Muhammad’s mother, Amine Hatun, of whom I had dreamed while listening to the Mevlit prayers.”

Although Berlin fails to excite Raif Efendi at first, he becomes more enthusiastic after realizing that this young artist may be wandering the streets of Berlin like him. She is: Raif comes across her one day in the museum, when she sits next to him on the bench across from the painting. Raif fails to notice she is the subject of the painting, though; his attention is directed elsewhere: “her skirt was short and her legs uncommonly shapely… Throwing one leg over the other, she revealed her leg well above the knee. I realized then that I was blushing—yet again.”

Sabahattin Ali wrote the novel in four months, from November 1940 to February 1941, while serving in the Turkish military. It was originally published in the Turkish newspaper Hakikat, where it was serialized in forty-eight parts. Readers of Hakikat found the novel weird; the serialization was a failure. The book version appeared in 1943, at a time when German influence was making itself increasingly felt in Turkey: racist clubs were becoming popular throughout the country; suspected communists, Ali included, were being watched by MIT, Turkey’s intelligence agency. In 1940, a magazine article denounced Sabahattin Ali as an effeminate degenerate. Ali was accused of poisoning Turkish youth with his novels and short stories and was characterized as a slavish, cowardly man of impure blood.

In April 1948, after being denied a passport, Sabahattin Ali attempted to enter Bulgaria illegally, walking the border with Ali Ertekin, a migrant from Yugoslavia. Two months later, his body was found near the border city of Edirne (Ertekin would confess to the murder years later). By the time Ali’s death was announced, Orhan Kemal had been released from prison. Just a few years later, the Democrat Party won Turkey’s first freely held elections. A few weeks after that, Nazım Hikmet and Kemal Tahir were also released—Hikmet escaped to the USSR via Romania and was stripped of his nationality by the ruling Democrat Party. Tahir stayed in Turkey, where he became famous for his mixture of Marxism and Ottomanism.

Since its first publication, Madonna has sold more than seven hundred thousand copies. In March 2016, Turkish Librarians Association announced its most borrowed books of the year: Madonna topped the list. It was also the best-selling Turkish novel of 2015. In the 2000s, Ali gained a reputation as the greatest prose writer of 1930s and 1940s Turkish literature: critics and readers finally seemed to agree with Hikmet. Nowadays Madonna in a Fur Coat can be found in Turkey’s supermarkets, where it is sold alongside detergent and toothpaste.

Madonna in a Fur Coat, by Sabahattin Ali, was published in English for the first time by Penguin Classics in May, translated by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe; the paperback version will be out in March 2017.