Translations from the French by Mitchell Abidor

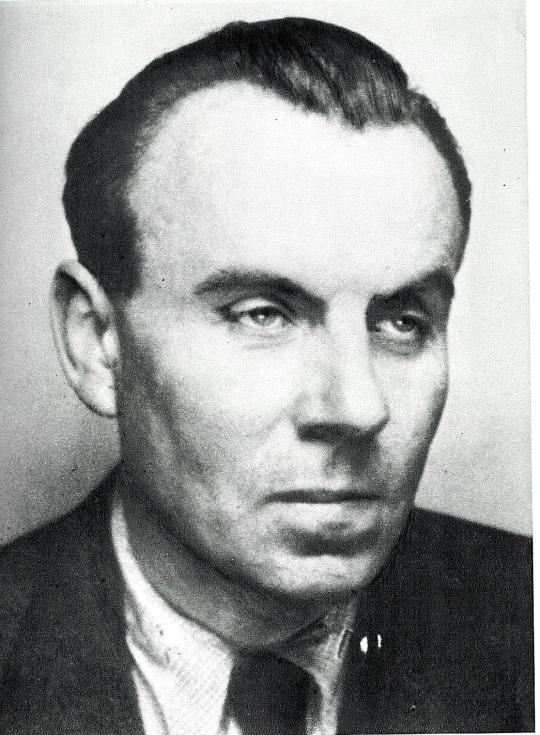

At the time of his death in 1961, French novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline remained an extraordinarily controversial and contradictory figure. He had been a cavalryman in World War I who collaborated with the Vichy government during the French Occupation and was later found guilty of treason. He was a physician who treated the poor in some of the worst slums in Paris, yet who was also a virulent racist and anti-Semite. He was a disillusioned humanist who turned misanthropist after seeing a world overrun with stupid human brutality. He spread myths about himself, and publicly attacked those who repeated them as truth. He loved the ballet, he loved animals, and was during his lifetime perhaps the most singularly despised man in France—a role he accepted and performed with undeniable gusto. Some said he was the embodiment of evil, others that he was merely and utterly insane.

He was also one of the most important and influential writers of the 20th century. He smashed forms and rewrote the conventions of what constituted proper style and storytelling. Without Céline’s bitter, sprawling, phantasmagoric black comedies, there would have likely been no Henry Miller, no Beat movement, no Jean Genet, no Kurt Vonnegut, Nathaniel West, Hubert Selby, Thomas Pynchon, William Gaddis, or a thousand others.

So then the question becomes, given Céline’s undisputed literary importance, why does so much of his work remain unavailable?

In 2009, fifty-five years after its original French publication, Normance, the last of Céline’s twelve novels to be translated into English, was finally released for the first time. Mea Culpa, an attack on communism written after a brief visit to Russia in 1936, was translated and released in the States in 1938 but never reprinted. In 2012, a small Quebecois publisher released a limited edition of three notorious pamphlets (some would call them “screeds” or “rants”) written by Céline between 1937 and 1941. It was expressly forbidden to sell or ship the book outside of Canada. Apart from the novels and two minor works (a play and a collection of ballets), none of Céline’s other writings are available in English. The amount of untranslated material is staggering—thousands of pages worth of essays, speeches, and correspondence.

Yes, Céline was an unpleasant fellow with some mighty harsh and unpopular ideas, but I’m hardpressed to think of another writer of similar stature, no matter how loathsome we may find his or her opinions, whose work has been so effectively quashed. Contrary to general perception, it’s not that these works have been banned. They haven’t been, at least not in any official manner. People are simply afraid of them, it seems, in a way they fear few other writers. People who have never read Céline call him a Nazi and dismiss the novels on that basis, often insisting, in fact, no one should read him. Academics treat him as if he will quite literally leap from the pages to inject poison into the minds of those who dare open his books. Publishers are apparently afraid of the repercussions of being associated with such a monster.

Funny thing is, over time the shrill, hair-pulling paranoia surrounding Céline has come to resemble a mere reflection of the ignorantly superstitious world against which he aimed so much invective. (On the fiftieth anniversary of his death in 2011, the French Culture Minister struck Céline’s name from the list of the five hundred most important French cultural icons because he was a nasty person.) It’s a situation that would have come as no surprise to the author of Journey to the End of the Night.

In 1934, after being approached by noted art historian Élie Faure to denounce the recent fascist riots in France, Céline wrote the following, excerpted from a previously untranslated letter:

… I absolutely refuse to line up on this side or that. I am an anarchist to the tip of my toes. I always was one and I will never be anything else. Everyone has spit on me, from Izvestia to the official Nazis, M. de Regnier, Comœdia, Stavisky, president Dullin, all of them in almost the same exact terms have declared me unacceptable, unspeakable. I haven’t done this on purpose, but it’s a fact. I’m fine with this, because I’m in the right. Every political system is an enterprise of hypocritical narcissism which consists in projecting the personal ignominy of its adherents onto a system or onto “others.” I admit that I live quite well; I proclaim loudly, emotionally, and strongly all of man’s common disgustingness, on the right and the left. I will never be forgiven for this. Since the death of the priests the world is nothing but demagoguery, shit is constantly flattered, and responsibility is rejected through ideological and verbal artifice.

There is no more contrition; there is nothing but chants of revolt and hope. But hope for what? That shit will start smelling good?

The ironic thing is that until 1937, with two masterpieces behind him (Journey and Death on the Installment Plan), Céline was considered a national treasure. Critics and readers alike hailed him as a revolutionary literary genius. They loved the shattered flow of his dark and hopeless poetry, his absurd humor, and his unrelenting, all-purpose misanthropy. In the novels he revealed himself as a non-denominational despiser of mankind, which he presented as a teeming mob of idiotic, cruel, drooling buffoons. He hated the French and the Germans alike, as well as the English, the communists, the Jews, the Jesuits, the generals and the foot soldiers, the rich and the poor. No one escaped his wrath, and everyone loved him for it.

But then in 1937 he published Bagatelles Pour une Massacre (Trifles for a Massacre), a pamphlet in which he ostensibly urged France to stay out of the inevitable war to come, as the results would be devastating. There was, however, a bit more going on in the screed as well, as the following excerpt reveals:

The only serious thing right now for any great man, scholarly writer, filmmaker, financier, industrialist, politician (and I mean the most absolutely serious thing) is to inconvenience the Jews. The Jews our masters, here, there, in Russia, in England, in America, everywhere!… Act like a clown, a rebel, someone daring, someone anti-bourgeois, the enragé righter of wrongs…The Jew doesn’t give a damn! Divertissements!… Babble! But don’t touch on the Jewish question or else he’ll burn your ass… Stiff as a board, they’ll have you croak in one way or another…The Jew is king of the gold of the bank and of justice…Through a straw man or directly. He owns everything…Press… Theater… Radio… The Chamber of Deputies… the Senate… Police… here and there… The great discoverers of Bolshevik tyranny emit a thousand eagle shrieks…that’s understandable. They beat their breasts till they bleed and yet they never never discern the swarming of the Yids, never track things back to the world-wide conspiracy…Strange blindness… (In the same way that in studying Hollywood, its secrets, its intentions, its masters, its cosmic racket, its fantastic bazaar of international stupefaction, Hériat nowhere sees the essential, the capital work of Jewish imperialism).

For pages on end he heaped bile on the Jews, accusing them of being behind the coming war, as well as every other war and evil known to man. He attacked the communists and Nazis as well, but few seemed to notice. The pamphlet sold 75,000 copies before being banned in 1939. When it was republished two years later, it became one of France’s top-selling books during the Occupation. But among critics, intellectuals, and the Left, the pamphlet was proof Céline was no longer a genial misanthrope like that quaint Mark Twain, or a slapstick existentialist like Samuel Beckett who would come later. He was pointing fingers, and worse—he seemed serious. It just wasn’t funny anymore.

Almost overnight, Céline’s literary reputation collapsed, which always struck me as more than a little ironic and baffling, considering that in historical terms France had long been held as one of the most anti-Semitic nations in Europe. It confirmed and exacerbated his disgust for humanity, and fed his anti-Semitic paranoia. Instead of being contrite, he used that burning disgust to publish two more pamphlets, L’École des Cadavres (TheSchool for Corpses) in 1938, and Les Beaux Draps (The Fine Mess) in 1941. In the latter, he examined Germany’s defeat of the French, and one has to wonder if the almost gleefully bitter tone doesn’t hint at a big Fuck You to his countrymen. After all, not only had the French population refused to heed his warning to stay out of the war—they went so far as to turn on him for even making such a suggestion. (It’s worth noting that until his death, Céline would insist that he was the last true French patriot.)

The German presence vexes them? Well what about the Jewish presence?

More Jews than ever on the streets; more Jews than ever in the press; more Jews than ever in the courtrooms; more Jews than ever at the Sorbonne; more Jews than ever in medicine; more Jews than ever in the theater, the opera, at the Français, in industry, in the banks. Paris and France more than ever handed over to the Freemasons and the Jews, more insolent than ever. More Lodges working backstage and more actively than ever. All of them more determined than ever to never surrender an inch of their farms, of their privilege to white slavery through war and peace up until the final jolt of the last confused native. And the French are quite content, perfectly in agreement, enthusiastic.

Such stupidity is beyond man. So fantastic a stupor reveals a death instinct, a gravitational pull towards the mass grave, a mutilating perversion that nothing could explain if not that the time has arrived, that the devil has captured us, that destiny has been fulfilled.

Needless to say, this did not help him reclaim his earlier popularity, and his overwhelming hatred of his countrymen only deepened. In later years (especially following the war when he was convicted of treason in absentia and facing the gallows) he would insist he wasn’t a collaborator during the Occupation—specifically that he had never written for the collaborationist papers. While technically true, he never wrote articles for them and was never paid, he did supply these papers with numerous letters to the editor, which were of course published in their entirety. The following, excerpted from a letter written shortly after the release of Les Beaux Draps, was submitted to Au Pilori, one of the more militant of the collaborationist publications.

…All of French public opinion is philo-Semitic and increasingly so! (We ate so well under the Mandel government). Who would dare swim against such a current? No one. Public schools (so Masonic) once and for all gave the French their hereditary enemy: Germany. The issue has been decided. The French never change their ideas. They are immutable and will die that way. They’re sickly and will never grow up. They are no longer of the age or have the taste for variations. They would rather die than think; they would prefer death to the abandoning of a prejudice. Who (they think) are the surest enemies of the krauts? It’s the Jews? Well then, five hundred times: Long Live the Jews!

Propaganda? Explanations? Demonstrations? Idle chatter? Zero! Everything is finished. The play is over. Wasted money, wasted time.

In order to re-create France it would have had to be entirely reconstructed on a racist-communitarian basis. We are ever farther away from this ideal, from this fantastic design. The lark has remained valiant and joyful; it still flies into the heavens, but the Gauls no longer hear it. Tied to, towed behind the Jews’ asses, kneaded in their shit up to their hearts, they find this to be adorable.

Three months earlier, once again revealing his contradictory (or perhaps merely anarchist) nature, Céline lobbied to spare the life of a French sailor who was scheduled for execution after claiming he sabotaged a German phone line. The efforts failed and the sailor was hanged. Afterward, Céline wrote the following to Dr. Augustin Tuset, a physician who had likewise fought to save the sailor.

And here we have an example of morality—There is no doubt that if this unfortunate had been a Jew he would have come out fine. It doesn’t matter what Jew: wandering disgusting showman. Why? Because all of Jewry would have immediately cast fire and flames, Mgr Duparc first among them, and all of Christianity of the Finistère and elsewhere would have taken up the cause of the little Jew—Countless petitions would have been covered in less than a week – The Krauts would have been so bothered that they would have released their prey. But an Aryan! In reality no one gives a damn – neither Jews nor Aryans give a damn. The proof is that they were ready to sacrifice two or three million more to defeat Germany, to begin 1914 all over again. Who is ready to sacrifice three million Jews? No one! And especially not the Pope.

The Aryan is a dog, fit only to kill. This is what all the Jews think, and the Aryans, too. In the case in question – imagine a Jew! All of Brittany would go into a trance; Rome the Lodges, Vichy, New York, the world. It’s the crime of crimes! For an Aryan? Weak protests lacking in faith and conviction, numberless [sic, read: few in number], sporadic, abnormal, dragged by the hair, rare—The fate of the Aryans is to die in the most normal of fashions: for the Jews.

(Worth noting here is that by the time of this letter numerous anti-Jewish laws had been enacted by the Vichy government across France. Jewish residents had been stripped of their citizenship, and several concentration camps had already been established.)

Despite the evidence of the above letters, Céline’s apparently monomaniacal hatred of the Jews was not quite as exclusive as it might seem. As seen in an excerpt from a 1942 letter to another collaborationist paper, he still had plenty of hatred left over for other groups as well.

…Count on me to throw the Jews, the Jesuits, the Freemasons, the synarchists, the priests, the English, the Protestants, the lukewarm, the soft, the vaguely anti-Semitic all in the same bottomless boat in the waters off Nantes. For me all these people are hanging on to this rotten civilization and must disappear. For us, racism for at least a few centuries.

In 1944 Céline returned to fiction with Guignol’s Band, but would not publish again for several years—not until after his self-imposed exile and a stretch in a Copenhagen prison awaiting extradition back to France to face his sentence. Once he began releasing novels regularly in the 1950s, the unflinching, hilarious misanthropy and nihilism of his earlier work was as harsh as ever (if not more so). Missing was the scalding, specifically antisemitic venom of the pamphlets and letters written during the Occupation. That never leaked into the novels except in a very broad and general manner. In his correspondence and statements to the press, however, he made it perfectly clear his attitudes had not changed, and he adamantly refused to apologize for anything he had said or written.

As despicable and loathsome a character as he presented himself to be (quite consciously and spitefully, I tend to believe), his final trilogy of novels—translated as Castle to Castle, North, and Rigadoon—may well be the most brilliant thing he ever wrote. He completed Rigadoon the day before he died, and shortly after finishing the novel he wrote one final letter, this one to his publisher, Gaston Gallimard:

My dear editor and friend,

I think it’ll be time we bind each other by another contract for my next novel, “rigodon”… in the same terms as the preceding one except for the sum—1500 new francs instead of 1000—otherwise I’m going to rent a tractor and smash in the NRF and sabotage all the baccalaureate exams! And I mean what I say!

Many, if not most readers will react to the few brief, unpublished letters and excerpts above with repugnant horror, and some will see them as proof of why such things should remain unavailable, hidden, tucked into a shadowed corner, forgotten (though writers may empathize with that last one). It’s easier not to think about those things that make us uncomfortable. But in spite of how ugly the contents and the sentiments behind them, there’s little denying that they’re still beautifully written (as much as the term “beautiful” could ever apply to Céline’s prose).

For those who would still deign to tell us what is proper and improper, what we can and cannot read for our own good, consider that since its original English publication, Mein Kampf has never been out of print. You can pluck a copy of the Turner Diaries off the shelf at Barnes & Noble. Goebbels Diaries and even that godawful novel of his are available, as are The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Céline at least wrote well, and these documents are of great historic and literary value—if only as a glimpse into the psychology of an important and complex artist. Consider also that we live in an age in which cable television is awash in fetishistic documentaries about the Holocaust and serial killers, where you can go online and watch videos of people eating shit or torturing animals, yet it’s Louis-Ferdinand Céline—in the grave for over fifty years—who frightens us. Somehow I believe the very notion would give him a chuckle. And then he would blame the Jews.