A group of Native Americans approach Alcatraz Island with the aim of reclaiming it from the U.S. government in 1969. (Ralph Crane/Getty)

In March of 1963, Alcatraz Prison in San Francisco Bay was closed down, and the few prisoners who still remained were transferred to other facilities. As per standard operating procedure, the following year the island, which housed the former penitentiary, was declared surplus federal property. According to the Treaty of Fort Laramie, signed in 1868 between the federal government and the Lakota Indians, all retired or abandoned federal lands were to revert back to the native peoples from whom they had been stolen. Apart from the members of a group calling itself Indians of All Tribes, or IOAT, very few people seemed to remember this.

Although a handful of Native American activists made attempts to reclaim the island in the years after it was declared surplus property, nobody paid much attention. Then in November of 1969, eighty-nine members of IOAT took up residence on the barren and rocky island, declaring it their own in an effort to call attention to the shabby treatment Native Americans had received at the hands of the U.S. Government. The occupation lasted some nineteen months, until June of 1971, and received a great deal of publicity.

The Alcatraz occupation was just one of several actions undertaken around the same time by what was known as the Red Power Movement, though most of it was concentrated on the West Coast. The targets of the assorted occupations were, without fail, either government office buildings (like the Department of Indian Affairs) or historic sites with a darkly ironic significance to Native Americans (like Wounded Knee and Mount Rushmore).

On the East Coast, Ellis Island ceased operations as an immigrant checkpoint and detention center in 1954. It, too, was soon declared surplus federal property. Over the next decade the island moldered; its neglected and unattended buildings fell into ruin. Then in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson linked the island together with the Statue of Liberty, placing it under the stewardship of the National Parks Service. The declaration didn’t help much. Although several plans for revamping Ellis Island were drafted, most were shelved as there were simply too many other things going on at the time. The only thing that changed was the arrival of a single Parks Department security guard, who was supposed to patrol the island a few hours every day.

Noting this situation, inspired by the events on Alcatraz, and frustrated by the lack of Red Power activity on the East Coast (where arguably Native Americans had it far worse than those on the West Coast), thirty-eight members representing over a dozen local tribes decided to occupy the island themselves to call attention to their plight and forward a few demands.

Like Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills, Ellis Island was an appropriately ironic target, as from a Native American perspective it essentially represented a welcoming gateway for the foreign invaders who stole the country from them. As symbols go, it would be much more powerful than Alcatraz, as soon as most Americans were reminded what Ellis Island was.

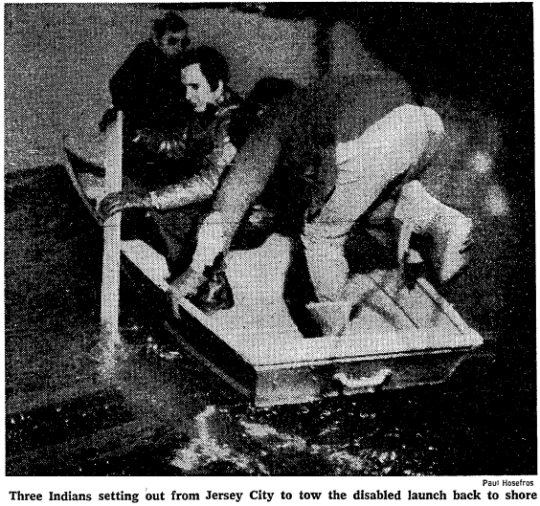

At about 5:30 on the morning of March 13th, 1970, the protesters gathered on the docks in Jersey City. As the rest waited on shore, eight activists, the first wave of the planned occupation force, climbed into a boat and headed for the island. A press release was sent to the media announcing the action, and soon local news broadcasts were reporting the protesters had landed on the island.

Unfortunately, they hadn’t. The boat’s engine had stalled thanks to a leaky gas line, and those first eight would-be occupiers were left adrift in the channel. Meanwhile, the National Parks Service, who only learned what was happening on Ellis Island thanks to those news broadcasts, got in touch with the Coast Guard, who sent out two patrol boats to safeguard the island’s perimeter, and that was pretty much that. No arrests were made, as no one actually landed on the island.

Afterward, John White Fox, a Shoshone Indian from Wyoming who helped plan and organize the attempted occupation, held a news conference in which he demanded a Native American cultural center be created on the island. He also demanded an end to pollution. He was about as successful as the occupation itself.

Even before the attempted Red Power occupation, Dr. Thomas W. Matthew, the nation’s first black neurosurgeon and chairman of the National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization, or NEGRO for short, was already in talks with President Nixon to let his group move onto Ellis Island. He proposed his group would repair and refurbish the buildings for use as home to a self-sufficient black community. The island would also offer rehab facilities for drug addicts. Matthew’s NEGRO had received a good deal of national press in the late 60s for its assorted venture capital endeavors, and despite the socially conscious plan he’d laid out for Nixon, his ultimate goal was to transform Ellis Island into a decidedly for-profit spawning ground for young black entrepreneurs.

Although Nixon never officially signed off on the plan, a few months after the abortive Native American occupation, Matthew and a few dozen supporters snuck onto the island and set up shop as if he had. A few weeks later, with no interference from the Coast Guard or Parks Service, everyone just assumed he had the right to be there and let him be.

Matthew and his group did some minor work toward rehabilitating the island, making assorted small repairs on a couple of the buildings and clearing away some brush, but conditions remained primitive, and the numbers on the island began dwindling quickly. The winter took a further toll on the occupiers, and by the autumn of 1971, the tiny handful remaining gave up and went home. In 1974, representatives of the National Parks Service would report it seemed Matthew and NEGRO had done little if anything to make improvements to the island. In 1973 Matthew himself, who had a checkered criminal history (mostly for assorted financial improprieties) was convicted on federal Medicaid fraud charges. He would insist to the end he had done little wrong, and was the target of a character assassination plot spearheaded by the Nixon administration.

Only a few weeks after the last of Matthew’s supporters vacated the island, still a third group of disenfranchised Americans took their fight across the channel to an even more symbolic (and easily defensible) site. If you have a beef with what you see as the federal governments failure to promote the blessings of liberty, where else can you go?

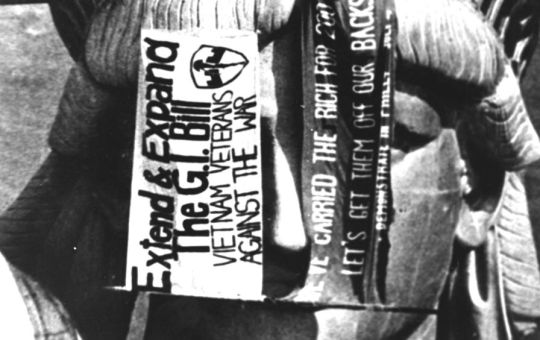

On December 26th, 1971, the same day similar protests and occupations were held around the country, fifteen members of Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) occupied and barricaded themselves inside the Statue of Liberty in order to protest America’s continued efforts in the war in Southeast Asia. Occupiers flew an American flag upside down from the statue’s crown and posted a note on the door directed at President Nixon, stating they would leave when he provided a specific date on which American efforts in Vietnam would cease.

While most of the other similar protests around the country that day lasted only a few hours, the VVAW occupation of the statue went on for two days. When a court order was delivered insisting they vacate the premises, they did so peacefully. Unlike the Native American and African American efforts, the VVAW protest was not only high-profile, the protesters themselves received a good deal of public support for their actions and intent.

Vietnam Veterans Against the War in 1976. (Courtesy of VVAW Inc)

The Statue of Liberty occupation was considered such a success another group of VVAW protesters returned and occupied it yet again on June 6th, 1976, this time to call attention to the plight of Vietnam vets following the end of the war. But the mood of the nation had changed, and sympathy was harder to come by. They were all quickly arrested by Parks Department police.

In 1977, a group of Iranian activists briefly took control of the statue in order to protest the Shah’s long and bloody record of human rights violations, as well as the US government’s continued support of the Shah’s regime. A few months after the Iranians were booted out, 29 members of the New York Committee to Free the Puerto Rican Nationalist Prisoners infiltrated the statue and hung a Puerto Rican flag from the crown. Among other things, they demanded Puerto Rican independence, immediate pardons for all political prisoners being held in Puerto Rico, and an immediate end to all discrimination against Puerto Ricans in the United States. After eight hours, the Parks police stormed the building and arrested them.

Perhaps noting that however peaceful they had all been, six occupations (or attempted occupations) over a seven year span was a bit excessive, in 1981 the National Parks Service finally got down to fundraising in earnest to regain legitimate control of both Ellis and Liberty Islands. The plan was to transform Ellis Island into a tourist attraction and refurbish the Statue of Liberty (including improved security measures) before its 1986 centennial. A cleaned up and revitalized Ellis Island, complete with museums, historic reconstructions, and several gift shops, officially opened to tourists in 1990. No one has tried to occupy it since, and now that it’s back in business as a National Monument, Native Americans no longer have any claim on it.