If you were able to spend 2016 immersed completely in the world of books, I genuinely envy you. As for myself, I think asking for words on paper to make up for the general horribleness of so much of the rest of lived experience might be putting too much pressure on them. It takes great concentration to impose sense on horizontal lines of text when sense seems to be seeping out all around you. And even if you manage, for an afternoon, to forget about reality in the space of two covers, you’ll look up from the last page and remember that reality has not forgotten about you. And so what, to quote Missing Persons, are words for when no one listens anymore? The answer depends on what you’re reading. At the end of the day, books are the only available technology capable of transmitting our dreams to one another as repackaged realnesses, each one an option for what another life might look like, a satellite porthole onto the orbital planetoids known as other people. Below are fifteen model worlds worth aspiring to and what they offer is not escape from the present, but a novel interface with it. The world of books is our world.

—JW McCormack

The Revolutionaries Try Again by Mauro Javier Cardenas (Coffee House Press)

The best book of the year and the reason this list exists is also proof that James Joyce is alive and well and splitting his time between Ecuador and the Bay Area. The revolutionaries of the title are a collection of ex-students, devastated by their fractious adulthoods, who reunite to take advantage of their home country’s vulnerable government. The opening image of a lighting bolt striking a pay phone is the ideal set-up for the following series of collisions between English and Spanish, thought and expression, the social and the personal, prose and poetry, finding wholeness in fragmentation until the reader is completely attuned to a style as perfectly realized as it is unique in all fiction. The Revolutionaries Try Again is such a wonder of composition that its very existence is an argument for literary consciousness as ongoing experiment.

The Babysitter At Rest by Jen George (Dorothy, a publishing project)

This collection of art brut short stories is a primer on what it feels like to be young and desperate, even if the stories themselves move between surreal encounters with phantom lovers and pornographic phantasmagorias set in schools and hospitals, where the institutional air acquires a certain porousness. Every young writer reckons on some level with the contemporary atmosphere of minimal employment, isolating education, the impossibility of privacy and the ubiquity of etiquette; George’s method is to pump everything full of helium until the ridiculousness of it all is laid giddily bare.

Private Citizens by Tony Tulathimutte (William Morrow)

Quite simply, a book it seems just about everyone would like to find in the glove box of a rental, stuffed into a time capsule or dog-eared in a bus station. Devious is the mind that fails to identify with this lucid novel of contemporary Americana, which follows four millennials through the post-University wilderness of protests, start-ups, and web porn. For all its force as painfully-recognizable panorama, Private Citizens is also a savvy rejoinder to the treatment this latest, shat-upon generation has received from their elders; Tulathimutte initially assigns each of his leads a type, daring us to mistake them for updated Breakfast Club cartoons, only to delve into their deeply-rooted pathologies, romantic misfires and the panicked sojourns into degradation that pass for day jobs. The result is a lively set of misadventures populated with a cast possessed of a rare humanity, acquired at enormous cost.

The Mirror Thief by Martin Seay (Melville House)

Less on-the-surface experimental than some of titles on this list, Mirror Thief is the year’s best hefty, character-driven novel-qua-novel, with chase scenes, mysterious strangers and spies whose intrigues span roughly four hundred years. We begin in 2003 with an Iraq War veteran tracking a mysterious gambler through a Las Vegas casino, then cut to West Coast beatniks on the verge of a mid-century mystery whose true nature is disclosed in Sixteenth-Century Venice. Erudite and action-packed, Seay’s novel is a yarn for all time that stacks up handsomely beside the likes of Jorge Luis Borges or Robert Louis Stevenson.

Dating Tips for the Unemployed by Iris Smyles (Mariner Books)

The title isn’t just a cuteness, this is a practical book for impractical people. In this chronicle of one woman’s navigation through the creeping normalnesses of 21st century life, you will find helpful tips like “Never date someone more or less miserable than you,” translations of party talk, and ideas for board games amid advertisements for home courses in snake handling, dream interpretation guides, and a novelization of Weekend at Bernie’s 2. And yet, there’s so much more than novelty at the heart of Dating Tips, which is ultimately a classical reckoning with modern love and a sure way to turn a disappointing day around or find solitary delight while fully clothed.

Trysting by Emmanuelle Pagano, tr. by Jennifer Higgins and Sophie Lewis (Two Lines Press)

Pagano’s first book in English contrasts different vignettes, none of them related by scene or character. Like the books of Marguerite Duras or Maggie Nelson, each fragment builds upon the other, managing to paint a picture of every single stage of being in love. These vignettes range from a couple of sentences to about a page, and reveal love in all its guises. A woman is woken from her sleep every night by her partner coming to bed. A man searches for his lover for years, only to find her featured in a documentary, still beautiful, though filthy. Another woman spends her life plucking hairs from her husband’s back. These moments are dazzling in their personal specificity, and together they create a universal experience of love, one in which you can simultaneously witness every relationship you have ever had, those you have witnessed from the sidelines, and all those loves you have only imagined and have been lost from their very conception.

Memoirs of a Polar Bear by Yoko Tawada, tr. Susan Bernofsky (New Directions)

The story of one writer’s Eastern Bloc beginnings and the struggle of two generations of her progeny and, yes, they are polar bears. What could have been frivolous in the hands of another writer acquires poise and implication, as German-language writer Tawada is deadly serious on the subject of the daily toil of the circus, labor movements, interspecies love and the thrill of invention. Central to the story are the intricate routines that the polar bears enact before their big top audiences, which seems an argument for insisting on one’s own peculiarity in the shadow of strict accord.

The Vegetarian by Han King, tr. Deborah Smith (Hogarth)

A novel of male domination, starvation and madness, The Vegetarian is a nightmare in three parts. First there is Yeong-Hye’s husband, who responds to her decision to give up meat with violence, then there is Yeong-Hye’s video artist brother in law, who enlists her in a pornographic fantasy, and finally Yeong-Hye’s embattled sister. The clipped tone is studiously unsentimental, the frailty of the characters beautifully rendered, as though weakness and insanity were themselves a rebuff to society’s emphasis on strength and unity. This is a pitch black book—I’m pleasantly surprised by its popularity—and one that makes Lars Van Trier look like Frank Capra. The most salient critique on structural power to appear in years.

Madeleine E. by Gabriel Blackwell (Outpost19)

A unique, curvilinear collage of texts found and imagined, Madeleine E., circles Hitchcockian themes of doubled identity and filmic consciousness, alighting on everything from Slavok Zizek and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Crack-Up” to Francois Truffaut and Kim Novak along the way. It’s also a biography-in-fragments that fingers the cracks in its own composition and emerges with a unique form that’s neither quite fiction, essay, or film critique but partakes of the pleasures of all three. Blackwell takes his cues from David Markus in his configuration of a mind by annotation of its influences, but pushes the envelope of the medium even more by suggesting that a person is that imposter we glimpse between the scenes.

Infidels by Abdellah Taïa, tr. Alison L. Strayer (Seven Stories Press)

The latest from prolific writer/filmmaker Taïa is the story of young Jallal who grows up in the Morocco underworld under the tutelage of his mother, Slima, who is both a prostitute and a saintly mystic. In alternating, largely dialogue-driven chapters, mother and son navigate the cruelty of their surroundings through a mélange of Arab pop music, Marilyn Monroe, and the promise of heaven. Jallal eventually falls in love with Mouad, a Belgian convert to militant Islam whose secrets lead Jallal and Slima both to salvation and destruction. Revolutionary for both in terms of content and the circumstances of its composition (homosexuality is a crime in Morocco), Infidels is a much larger on the inside than its slim page count would seem to suggest.

Gesell Dome by Guillermo Saccomanno, tr. Andrea G. Labinger (Open Letter)

The seedy double life of an Argentinian resort town is depicted in snaking storylines in this noir masterpiece, which reads not unlike Twin Peaks by way of Roberto Bolaño. Opening with the outbreak of a kindergarten sex scandal and getting darker from there, Gesell Dome shows us a criminal government, a captive press, and an economy based on blackmail and fear mongering. For all its strength as a microcosm of failed statehood, it is the characters who make this 600+ page book a speedy read, including a cursed painter, a Pilates-obsessed crime wife, a supposed Nazi diaspora and a monster lurking in the forest. What more could you want?

John Aubrey, My Own Life by Ruth Scurr (NYRB Classics)

A towering whatsit of a book, John Aubrey, My Own Life is a biography of Aubrey—a founding English eccentric and collector who pioneered the form in his portraits of eminent friends—which takes the form of a diary by the writer himself, each entry traceable to a primary document, be it a letter, bulletin, or Aubrey’s own work in the natural sciences. This allows Scurr to channel her research into a full-scale recreation of Aubrey’s life and times that is as vivid a rendering of Cromwellian London as seems possible. Imagination and scholarship, as well as supplementary drawings, arrange the past into an elegant mosaic that also manages to overflow the boundaries of what a book can be.

Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett (Riverhead Books)

Pond is a quiet book. A woman goes to live in a cottage in rural Ireland, and nothing much happens, yet everything is strange. In Bennett’s work, you experience the defamiliarization of eating bananas for breakfast. The narrator wants to throw away her freshly-cooked stir fry into the garbage. The banalities not only work but become something strange and full of wonder. Bennett’s writing is steeped in Lydia Davis and has the wit and bleakness of Beckett. Outside the narrator’s cottage the Irish countryside reflects and reifies her loneliness. Over the course of the novel-in-stories, the narrator comes gently undone.

The Knack of Doing by Jeremy Davies (David R. Godine & Black Sparrow)

What do Kurt Vonnegut, sad white people, the Rosenbergs’ executioner, and a hypercube all have in common? I don’t know. But Jeremy Davies does. The stories in this collection run the gamut of Davies’ incredible and hyperliterate imagination, and are a reminder that being playful is of great importance to our humanity. Reader beware, these stories are a deadly serious labryinth of fun.

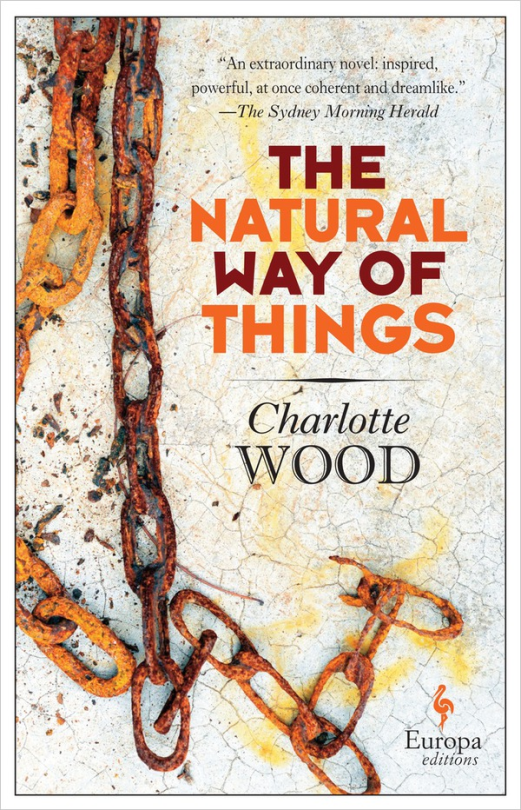

The Natural Way of Things by Charlotte Wood (Europa Editions)

A group of girls are captured and imprisoned deep in the Australian desert, as punishment for unruly behavior and their sexuality. Gradually we learn that they have all been involved with powerful men in some way, and are now forgotten by the company that’s imprisoned them, the playthings of their ever-more deranged jailers. Exploring what it means to hunt and be hunted, this book is vicious and prescient and astonishingly visceral. The Natural Way Of Things resonates with you long after you’ve read the final pages. A Handmaid’s Tale for end times, this is an important book about contemporary femininity.