All photographs by the author.

1.

There are roughly ten blocks between the theater where David Bowie watched rehearsals for Lazarus, and the studio where he recorded Blackstar. In his last years, we both lived between them, on opposite sides of Houston Street.

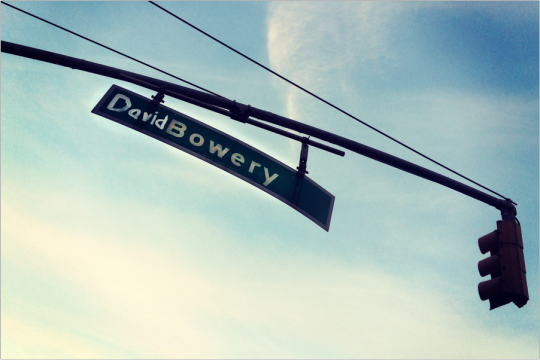

My side is the Bowery, known in real estate speak as NoHo (North of Houston). On the street where I live—a two-block stretch of 3rd Street known as Great Jones—is a chandeliered butcher shop occupying the spot where Basquiat worked, and died, of a heroin overdose. Twenty years before his time, Charlie Mingus’ heroin-addicted presence on this corridor is said to have birthed the term jonesing.

I’ve passed a decade in Brooklyn, but never before now lived in Manhattan and love being a downtown kid, stepping through the door and onto crowded streets, passing CBGBs—now a skinny pants boutique I’ve never entered—on my way to buy groceries, or borrowing books from a library branch housed in the one-time factory of Hawley & Hoops’ Chocolate Candy Cigars—that Bowie lived above, in a modern penthouse perched atop the turn of the century brick building.

For twenty-four months, barring the occasional trip to Central Park, I’ve lived below 14th Street and in this time Bowie loitered here too, sipping La Colombe’s double macchiato, fetching chicken and watercress sandwiches at Olive’s, or dinner supplies at Dean & DeLuca. One day I’d catch him on the street, I figured, hailing a cab or taking out the recycling in his flat cap and sunglasses, and when I did my well-worn New Yorker discretion would be jettisoned as I tried, and likely failed, not to cry.

I didn’t, of course, know that for most of the time we were neighbors David Bowie was dying. Today I walk the familiar stretch of blocks to his building, eyes tearing, I tell myself, from the frigid, bone-dry air. At the front entrance, a group of fans stand gutted, surrounded by news trucks, generators, vulturing reporters.

A growing pile of daisies, tulips, roses, daffodils leans against the wall, along with a few photographs, a pair of silver glitter heels, a Jesus candle with Ziggy Stardust face. Tucked here and there are handwritten notes: Look out your window, I can see his light and We are all stardust and Hot tramp, we love you so.

Everyone here, news crew aside, feels known somehow, the mood is gentle, polite, quiet. Too quiet, I realize, when someone plays “Life On Mars?” from a tinny smartphone speaker. As the closing strings swell, a woman turns to me to say through tears, “I love this song!” All I can do is nod, “I know!” and take comfort among fellow kooks.

A pair behind me wonders aloud about a “world without Bowie,” and while I know what they mean—the way some people feel like a force and invincible—you could argue we’ve been living in such a world for a long while. David Jones-ing.

2.

Three days earlier, on the night of Bowie’s 69th birthday, I danced in my kitchen to the foppish, falsetto, “‘Tis a Pity She Was a Whore,” delighting in his rude lyrics and wild whooping. Later at a dinner hosted for the birthday of a friend, I commented on Bowie’s continuing fixation upon mortality, but also his energy, sly humor, return to form, exclaiming, not tentatively, “Bowie’s back!”

I was thrilled he’d finally slipped the ghost of what he called, “my Phil Collins years.” In one of the endless interviews now flooding my screen in text and video, he explains, “I was performing in front of these huge stadium crowds and at that time I was thinking ‘what are these people doing here? Why did they come to see me? They should be seeing Phil Collins.’ And then that came back at me and I thought, ‘What am I doing here?’ It’s a certain kind of mainstream that I’m just not comfortable in.”

Like the divisiveness of fat and skinny Elvis, there were those of us who fancied ourselves glittering, androgynous, apocalyptic half-beast hustlers who bought drugs, watched bands and jumped in the river holding hands, and there were others, contentedly jazzin’ for Blue Jean.

When, in your Golden Years, your mentor of not only music but all things relevant—art, clothes, books, films—enters his Phil Collins Years, suddenly high-kicking in Reeboks and staring in Pepsi commercials, how not to feel betrayed?

I took it personally, coining the unforgiving term David Bowie Syndrome. As a burgeoning artist, I feared (a scaled-back version of) his creative arc with my whole heart—reaching the greatness of Bowie’s 1970s only to follow it up with Let’s Dance. To say nothing of Tin Machine. Like many old-school fans, I’d stopped tuning in to modern Bowie to keep my vintage Bowie flame flickering.

In my most youthfully caustic moment, I joked that Bowie’s personal Oblique Strategies deck—that famous stack of cards, creative prompts such as Ask your body, Abandon normal instruments, and Courage! allegedly used when Bowie and Brian Eno recorded Low and Heroes—should be made up of cards that all read, simply: Call Eno.

Unfair, untrue. Kindly allow this counterpoint mea culpa admission: I secretly love the ham-fisted, cringtastic video for Dancing in the Street.

3.

On the third day after Bowie’s death I step outside, wondering if I’ll still hear his presence hum. Just feet from my front door I’m greeted by his face gracing one of two large posters advertising Blackstar. Well hey there, Mr. Jones.

They’re wet with wheat paste and like a teenage fangirl I consider stealing one, but then notice a smaller poster hung next to them, featuring the Sesame Street characters peering out joyously, encouraging me to attend an event entitled… Let’s Dance!

I accept Bowie’s cosmic joke, had it coming I suppose, and briskly hoof it to Union Square where at the farmer’s market I find apples, apple cider, cider doughnuts and not much else. My gloveless fingertips smart as I pocket change and consider the possibility that the visitation was an invitation to dance through the sorrow. A bit maudlin perhaps, but then, so was Bowie.

When I return home the Blackstar posters are gone. In under an hour someone has pasted them over with clothing and gym ads—leaving all the posters on either side for the length of the street untouched. Like Steppenwolf’s Magic Theater, the message—whatever it was—had appeared and just as quickly vanished.

My feet walk me to Bowie’s memorial, which has exploded in a heap of bouquets, black bobbing Prettiest Star balloons, cha-cha lines of platform heels, disco balls, eye shadow, quarts of milk, British flags, drawings and paintings of Bowie’s many incarnations, fuzzy spiders, bluebirds, boas, vinyl copies of David Live annotated Forever in thick silver marker.

A giant orange tissue paper flower hangs from a nearby tree, electric blue eye at its center, petals edged in lyrics: Give me your hands, because you’re wonderful! Let the children lose it, let the children use it, let all the children boogie.

Here and there are tucked personal notes: You taught me that weird = beautiful,and: When I was a teenager I wished I could check off “David Bowie” for both my gender and my race. I still do.

“Taking away all the theatrics…” Bowie said, “I’m a writer. The subject matter…boils down to a few songs, based around loneliness, isolation, spiritual search, and a looking for a way into communication with other people. And that’s about it—about all I’ve ever written about for forty years.”

Perhaps, then, my “Let’s Dance” visitation was an anti-message, a warning against wasting creative juju by pandering for cash. Of course, Bowie made not a dime (relatively, and thanks in large part to shifty management) from his artistic era I find most inspiring. The seed of the fortune that brought him financial security was that very song. So what then?

When I return home, Bowie’s spot on the wall has been papered over yet again, all white this time, as though to say, as he has when pressed to interpret his lyric’s meaning, “nothing further,” “you figure it out,” “space to let.”

4.

I rise before the sun, pull on bright turquoise tights and red clogs and walk the cobblestone of Lafayette Street in the dark. Collar up, breath ghosting, I feel as I secretly do in all such moments, like the cover of Low, or The Middle-Aged Lady Who Fell to Earth. Car headlights slide over me as I approach the memorial that is, it appears, being dismantled.

I quickly make the photograph I awoke imagining: my platforms meeting Bowie’s shore of flickering candles, cigarette butts, stray boa feathers, sea of glitter. Beside me a sweet lone man sorts out the dead flowers, shuffling handmade things to one side, candles to another, not tossing it all as I first suspected, but tidying up, preparing for another day.

What drew me into this frigid darkness, half dressed in pajamas? Perhaps a need to meet Bowie toe to toe, promise to honor the contract, all in, heart wide, funk to funky.

Put on my red shoes and dance the blues.

“I don’t think (the act of creation is) something that I enjoy a hundred percent. There are occasions when I really don’t want to write. It just seems that I have a physical need to do it…I really am writing for myself.”

Before Blackstar, the last time I know of Bowie creating under extreme duress is when making the album Station to Station—which coincidentally also opens with an epically long titular song wherein a man yelps from the darkness, singing with pride and pain about a fame that has isolated him beyond measure.

As the Thin White Duke, Bowie sings with bitter irony, It’s not the side effects of the cocaine!I’m thinking that it must be love! It’s well known that Bowie, living for a year (1975-1976) in his despised, self-chosen, wasteland of Los Angeles, had fallen victim to a kind of Method Writing, unable to escape in life the character he’d crafted to hide behind on stage.

Subsisting on a diet of cocaine, chili peppers and milk, he grew paranoid, hallucinating, allegedly dabbling in Black Magic and storing his jarred urine in his refrigerator. I was six years old at the time, living less than a mile from Cherokee Studios where Station to Station was in session, and smudging my mother’s brand new Young Americans vinyl with powdered sugar fingerprints.

He said of the following album, Low, “It was a dangerous period for me. I was at the end of my tether physically and emotionally and had serious doubts about my sanity. But I get a sense of real optimism through the veils of despair from Low. I can hear myself really struggling to get well.”

It’s the pale, shimmering hope that makes Low my favorite of allof Bowie’s offerings, but for Station to Station’s Duke of Disillusion it’s too late—for hate, gratitude, any emotion. It’s not, however, too late to lay himself bare in the work: there’s no reach for sanity, just a man collapsing while still directing, as the camera rolls.

Blackstar has been called a gift, and on “Dollar Days,” a song that describes his effort to communicate in the face of death, Bowie breaks the fourth wall to address this directly: Don’t think for just one second I’ve forgotten you/I’m trying to/I’m dying to(o).

I believe as an artist he had no choice, no other way to confront his circumstance other than to talk himself through it, put it in the work.

The profound generosity of Blackstar, and a vast swath of Bowie’s creative output, is that in this most intimate conversation with death, god, time, himself, we’ve been invited to listen in.

5.

What makes a good death? Bowie withdrew from the public in the last decade and was characteristically silent regarding his illness, in this tell-all age (that owes him not a little for its status quo “tolerance” of Chazes and Caitlyns). He was also, in his time post-diagnosis, compelled to make his most raw and exposing work in years, and between the play and album, likely spent a long part of each day in their pursuit, while presumably also tending to his needs as a father, husband, friend, man.

In Walter Tevis’ book The Man who Fell to Earth—the basis of Nicholas Roeg’s film that inspired Bowie’s production Lazarus—stranded, despondent space alien Thomas Jerome Newton records an album called The Visitor: we guarantee you won’t know the language, but you’ll wish you did! Seven out-of-this-world poems! Newton explains it’s a letter to his family and home planet that says, “Oh, goodbye, go to hell. Things of that sort.”

Bowie’s seven-song swansong, Blackstar, is rather more generous, and from a writer notorious for lyrical slipperiness, layered meanings, a cut-up technique (copped from Burroughs) that spawned lines about Cassius Clay and papier-mâché, its text is frequently plain-spoken and direct.

Even my favorite frolic sounds a combative calling down of his illness, time: Man, she punched me like a dude/Hold your mad hands, I cried/She stole my purse, with rattling speed/This is the war. It would not be the first time Bowie referred to Time as a “whore.” (see: Aladdin Sane.)

In the title video’s most vivid sections, Bowie becomes god—less vengeful than dismissive—singing, from heaven’s attic, a swaggering takedown of Bowie himself: You’re a flash in the pan, I’m the great I am. (From Exodus: And God said unto Moses, I AM THAT I AM: and he said, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I AM hath sent me unto you.)

His button eyes in both videos suggest a puppet, and so the presence of a puppet master, but I don’t read these images as signs of deathbed conversion. Bowie was a spiritual seeker who borrowed magpie style—in this case from Egyptian, Kabalistic, Christian and Norse iconography—to create a language to give voice to his fears and dark entries.

“If you can accept—and it’s a big leap—that we live in absolute chaos, it doesn’t look like futility anymore. It only looks like futility if you believe in this bang up structure we’ve created called ‘God’.”

In his last gestures Bowie answered not God, but himself, regarding the way he’d lived, and in particular, as an artist. The pulse returns the prodigal sons suggests that the characters he inhabited—some regrettable, but not irredeemable—are with him as he assesses the intentions behind, and perceived short-comings of, his creative offerings: Seeing more and feeling less/Saying no but meaning yes/This is all I ever meant/That’s the message that I sent/(but) I can’t give everything away.

In his almost unbearably haunting last video, it seems we’re finally invited to meet David Jones, or Bowie playing Jones. Jones the man lies in bed, clutching a blanket with those mortal, frightened hands. Nearby the writer manically, fretfully reaches for immortality, while Bowie the performer, dutifully dances to the end.

“There’s an effort to reclaim the unmentionable, the unsayable, the unspeakable, all those things come into being a composer, into writing.” “You present a darker picture for yourself to look at, and then reject it, all in the process of writing. I think that’s what’s left for me with music. Now I really find that I address things to myself. That’s what I do. If I hadn’t been able to write songs and sing them, it wouldn’t have mattered what I did. I really feel that. I had to do this.”

This morning I remembered where I’d seen the writer’s austere, black and white striped costume before: the program for the 1976 Isolar tour, wherein Bowie self-consciously poses with a notebook or makes chalk drawings of the Kabbalah tree of life. Isolar is a made up word—and name of his current company—said to be comprised of isolation and solar.

I love this costume—a kind of artisan worker-bee uniform. There are satin kimono-sleeved ass-baring rompers for when its time to present the work, but when making it, roll up your revolutionary sleeves and get to it.

1976 saw the success of Station to Station, the premiere of The Man Who Fell to Earth and the recording of The Idiot and Low. It was not the most grounded time for Bowie personally (to understate it), but arguably his most vital creatively, and this nod to the continuum of creative spirit seems to suggest that the artist dies, but through the work, like Lazarus, rises again.

6.

So what, then, is a Blackstar? Perhaps a marked man, a sly reference to Elvis’ song of the same name whose lyrics include, Every man has a black star/A black star over his shoulder/And when a man sees his black star/He knows his time, his time has come.

Although Bowie did not, as rumored, write “Golden Years” for Elvis, he did find (somewhat bashful) significance in their shared birthdays, took pains to catch his concerts, had his white jumpsuit copied to wear while performing “Rock and Roll Suicide,” modeled his own costume in Christiane F after Elvis’ ensemble in Roustabout, and perhaps his Aladdin Sane red/electric blue lightening bolt was inspired by Elvis’ signature gold one. Which is to say, he likely knew of The King’s “Black Star.”

Blackstar could also suggest the theoretical transitional state between a collapsed star and a singularity—a state of infinite value in physics, a metaphor for immortality.

I’m not a gangstar/I’m not a film star/I’m not a popstar/I’m not a marvel star/I’m not a white star/I’m not a porn star/I’m not a wandering star/I’m a star’s star/I’m a blackstar.

“Sometimes I don’t feel as if I’m a person at all…I’m just a collection of other people’s ideas.” Is Bowie simply claiming his right to throw off all mantles?

The car crash that is the documentary Cracked Actor opens with a reporter asking, “I just wonder if you get tired of being outrageous?” “I don’t think I’m outrageous at all,” Bowie throws back, miffed. The reporter persists, “Do you describe yourself as ordinary? What adjective would you use?” Bowie searches his brain for an appropriate response to the inane question and finally lands upon: “David Bowie.”

Or perhaps, as Isolar suggests, a Blackstar is someone hidden in plain sight. In an interview that seems more therapy session, with Mavis Nicolson in 1979, mostly drug-free and grounded Bowie speaks of the appeal of life in Berlin, whose physical wall seemed to mirror his psyche. Without referencing himself or the characters he’s inhabited, he describes an isolated figure who finds no home in the world, but instead creates “a micro world inside himself.”

When Nicolson suggests that as an artist Jones must keep himself from love, he rejects the idea outright, but when gently pressed about the demands of relationships in actual life and not “from afar,” he concedes, extending his arms before him like a shield, “No, love can’t get quite in my way, I shelter myself from it incredibly.”

The moment is so resonantly raw that the two break into manic humor, shifting to the story of his eye injury in a childhood fight over a girl, wherein he laughs and says, “I wasn’t even in love with her.”

In “Lazarus,” the dying Jones sings: everybody knows me now, and perhaps that is so, as much as it ever could be for a man who spent an artistic career in self-sustained exile.

And why shouldn’t David Jones have been—with the exception of a few deeply druggy years—free from the curse and blessing of being Bowie? What are we owed by our artists?

7.

Blue, blue, electric blue, that’s the colour of my room.

The Bowie song that forever circles my brain describes a writer waiting for the muse, describing the loneliness and blessing of the electric blue of creation. Vishuddhi, or the electric blue throat chakra of Hindu tantra, is associated with the vocal cords, communication, creative expression, one’s inner-truth.

For sixteen months I lived in Berlin’s Schöneberg quarter, around the corner from 155 Hauptstrasse and the apartment that song was composed in and of. I’d pedal my bike past and nod to the ghost Bowie inside, still wondering and waiting for the gift of sound and vision.

It’s the seventh day since Bowie’s death, the final day of shiva I’ve sat beneath his window. I’ve never much understood funerals, always felt they were for a “living” that didn’t include me, but this has been different.

Over this week I’ve shared glances with occasional bleary-eyed oldsters coming or going from where I’m headed or have just been–there have been no young folk to speak of and no platform boots necessary to recognize the kooks.

Today, from a block away, I spy a pair of women making the pilgrimage. The taller of the two—who for one moment I mistake for Patti Smith—has Smith’s hair, a floor-length bright blue shearling coat and an armload of exquisite orange, flame-tipped roses.

Trailing my comrades I think of Smith’s line in Woolgathering when, upon being given a dandelion, she asks, “What could I wish for but my breath?”

At Bowie’s door the energy feels less personal, dissipating. After the roses-bearers depart, a lone woman and I stand shivering before the diminished pile of offerings framed by narrowed police barricades: plastic-wrapped bodega flowers and a few handmade items, the most prominent being a cigar box shrine with a Halloween Jack eye patch and what seems a bunch of random stuff tossed in. The woman plays “Starman” on her phone, and rather than poignant, it’s just sad.

A years later follow-up to his first solo release, “Major Tom,” “Starman” takes the isolation of planet earth is blue and there’s nothing I can do and turns it into an anthem where a cosmic DJ messiah tells us misfits not to blow it, ‘cause he thinks it’s all worthwhile.

The 1972 Top of the Pops performance famously featured Bowie’s flirty finger wagging at the viewer, and casually intimate embrace of Mick Ronson, which blew the minds of much of Britain and beyond and marked Bowie as a more than a one-hit wonder. I silently give thanks to many, including Bowie, not to live in a world where a rock and roll arm thrown over a shoulder can cause a stir.

Over the song’s fade out the woman shrugs and says something about bears—at least I think that’s what I hear. I smile and nod remotely, then realize she’s drawing my attention to the carefully rendered Ziggy Stardust teddy bear—complete with lightning bolt and guitar—hanging from the police steel.

This bear abrades me for no good reason. A few young women pass by on their way into American Apparel. “That was David Bowie’s house,” one says over her shoulder, and the other makes an “awww” sound like she might at the sight of a teddy bear, or the memorial of that musician guy that died the way people do—other people, older people. As they pause to take a selfie in front of Bowie’s memorial offerings I turn and nearly sprint downtown.

I learned in this week of Bowie Internet inundation that he trailed these streets too, often at dawn, in solitude, but right now I need Chinatown’s chaotic, smashing life. I’ll buy those killer clementine from that vendor on the corner, I think, and eggplant, scallion and ginger for supper.

I weave among cardboard boxes of dried silver fish and lotus root, tourists linked arm-in-arm in matching New York pom-pom hats, Chinese grandmas pushing plaid shopping carts in (Harold and) Maude braids. A man exits a hallway, arms loaded with red-ribboned funeral flowers. A chef in a paper hat leans against a wall, smoking beneath a pumpkin-sized, spinning dumpling.

Beneath crisscrossing wires strung with giant, glinting snowflakes, I warm my hands on a cup of milky tea and wonder when we’ll get winter’s first snow. Glancing up to cross Mott (the Hoople) Street, I wonder when the city’s details will cease to conjure Bowie.

I tuck dragon fruit into my sack, humming “Starman”—whose chorus melody is plainly lifted from The Wizard of Oz’s “Over the Rainbow.” Somewhere over the rainbow, bluebirds fly/Birds fly over the rainbow./Why then, oh, why can’t I?

In performance, Bowie sometimes coyly sung a mash-up of these anthems of longing for belonging. On “Lazarus” he sings, seemingly of his death, This way or no way/You know, I’ll be free/Just like that bluebird/Now ain’t that just like me.

Blackstar begins by naming the Norse village of Ormen. In Norse mythology, the rainbow bridge that connects this world to that of the gods is Bifrost, which translates as tremulous way. Tremulous—as in trembling—as Bowie does so heart-wrenchingly as he backs into the armoire and out of this world.

When he heard the call, David Jones, who could walk the streets of Manhattan undetected, slipped over the rainbow and into his own imagination.

But with generosity and courage it seems he did not fully recognize, David Bowie spent his life pulling back the curtain on the Great Oz, showing the man, his frustration and fallibility, questioning art-making and then making it anyway.

I fear in the end he imagined himself “a very bad man but a very good wizard,” when in fact the opposite was true. The droves of people gathered at his front door and around the world may have found the masks fascinating, but only as much as the man, and heart, behind them.

I imagine catching David Jones wandering past shop windows plastered with red New Year monkeys, beneath golden, swaying lanterns. I would thank him for Ziggy Stardust, whose hair my mother copied and Scary Monsters, whose poster graced my eleven-year-old bedroom wall. I’d say thanks for Low and Hunky Dory, which got me through hard times. Thanks for The Man Who Fell to Earth and The Hunger, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke. Thanks for Diamond Dogs, Heroes, Lodger, Station to Station. Thanks for creating a soundtrack for my life and the lives of my favorite people.

Thanks for being a fierce, literate libertine, giving permission when I so badly needed it and inspiration always. Thanks, from the strange kids, for saying, No love, you’re not alone! You’re wonderful!

On the afternoon of January 10th, in what I later learned were the last hours of Bowie’s life, a double rainbow drew me from my desk and to the window. It arced across the skyline and ended at the Empire State Building, so strikingly that fire fighters in the station across the street took to the emergency dispatch microphone to exclaim to the neighborhood, “There’s a rainbow!”

As the first snow falls over Chinatown’s back alleys, I think: rainbowie!

There’s a Starman, over the rainbow, way up high, and he told me—let the children lose it, let the children use it, let all the children boogie.