The Believer Book Awards honor the best-written and most underappreciated books of the year. Awards are presented in the categories of Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, and, this year, for the first time, Graphic Narrative. Here are the 2020 winners and finalists.

Fiction:

Winner: Long Live the Post Horn!

by Vigdis Hjorth

(translated by Charlotte Barslund)

Verso Books

This is not an easy novel to recommend to people. When you tell them it is the story of a PR consultant who is tasked with helping the Norwegian Postal Workers Union fend off an EU postal directive, they don’t exactly rush off to their local bookstore. But Hjorth’s novel, her second to be translated into English, takes this seemingly dry subject and turns it into a fascinating exploration of what it means to live a life of purpose and conviction. Ellinor, the story’s thirty-five-year-old protagonist, lives a joyless existence, rarely communicating her needs to her family or to her equally detached boyfriend, Stein. Through her work on the postal directive, however, she is introduced to a community of mail carriers, who shift her perspective and show her how to take responsibility for her own life. Drawing on the writings of Kierkegaard and other philosophers, Hjorth’s novel emphasizes the power inherent in our most minute and mundane choices. It asks us to consider them as gifts, something to be treasured and attended to—like a letter from a friend, delivered to your door.

Finalist: What Happens at Night

by Peter Cameron

Catapult Books

In Peter Cameron’s seventh novel, a woman, who is sick with cancer, and her husband travel to an unnamed Arctic-adjacent country to adopt a child. After disembarking at an abandoned train station, they find lodging at the Borgarfjaroasysla Grand Imperial Hotel, a velvet purgatory populated by a mix of eccentric staffers and guests, including an aging lounge singer, Livia Pinheiro-Rima, who becomes the couple’s de facto guide to the region. Cameron is particularly skilled at crafting these kinds of minor characters: they hover between universal archetypes and bespoke oddities, animating a story that itself seems to exist between myth and realist fiction. Written in dreamlike prose, What Happens at Night is casually propulsive and full of surprises. Reading it feels like falling through a series of trapdoors.

Finalist: The White Dress

by Nathalie Léger (translated by Natasha Lehrer)

Dorothy

Can a book be a performance? The White Dress comes close, chronicling the journey of Italian conceptual artist Pippa Bacca, who traveled from Italy to Turkey in a wedding dress to promote world peace. All the books in Léger’s triptych are about women who have, to some degree, disappeared, and their considered relationship to image-making: the Countess of Castiglione, the subject of the first book, Exposition, was the most photographed woman of the nineteenth century; Barbara Loden, subject of the second, Suite for Barbara Loden, was a filmmaker and the star of the film Wanda; and in this book, Pippa Bacca, whose camera was stolen by the rapist who murdered her, filmed her own durational project. The White Dress is an imaginative dossier, almost a noir at times, and a digressive balancing act that circles not only its subject but Léger’s relationship with her own mother, as well as questions of haunting and absence.

Finalist: The Baudelaire Fractal

by Lisa Robertson

Coach House Books

Lisa Robertson’s debut novel is characterized by dissolving and permeable borders. Its narrator, Hazel Brown, says with little fanfare, “I simply discovered within myself late one morning in middle age the authorship of all of Baudelaire’s work.” She revisits her old diaries, reliving her itinerant youth in Paris. Her memories are awash in a sumptuous palette of oil paints and silky textiles, and always the presence of Baudelaire lingers like the warm and musky base notes of a perfume. Time, art, poetry, philosophy, fashion, history, criticism, and theory are woven together in Hazel Brown’s hypnotic and immersive narration. The novel never stops moving, drifting, blurring from one arrondissement to another, unfaltering in its feminist wandering.

Finalist: How to Pronounce Knife

by Souvankham Thammavongsa

Little, Brown and Company

The stories in Souvankham Thammavongsa’s debut collection explore the inner lives of Laotian immigrants and their children as they navigate the pains and promises of life in the West. A mother falls in love with the music of Randy Travis; a former boxer takes a job at his sister’s nail salon; and a printer of wedding invitations makes a bold prediction. Thammavongsa digs into the murkiness of displacement, classism, survival, and the myriad other complexities of navigating a new culture. Her prose is spare and unassuming, sometimes wryly funny, and often deeply moving. Through their frantic obsessions, their bored indifference, their quiet heartbreaks, and their little victories, Thammavongsa’s characters come alive.

Nonfiction:

Winner: The Lonely Letters

by Ashon T. Crawley

Duke University Press

This epistolary book captures the nature of longing like few other works do. Crawley’s character, “A,” writes to a loved one, an interlocutor called Moth, exploring the author’s intellectual connections, affections, heartbrokenness, blackqueer identity, yearning for sensuality, and, most poignantly, “the desire for friendship as a way of life.” The Lonely Letters is, as he writes, “an autobiography of loneliness.” This book is at once a compendium of letters, an epistemological study, and a consideration of Black performance and ways of being free. “The voice is a fugitive, it steals and is stolen,” A says, and elsewhere he asks, “What if it were possible to vibrate at the same speed and velocity as our favorite music, our favorite sounds?” In this spirit, he references the Black Pentecostal tradition, Harriet Jacobs’s autobiography, the writings of Sylvia Wynter and Fred Moten, and Twinkie Clark’s organ playing, among other sources of inspiration, locating the liberatory possibilities of each.

Finalist: A Fish Growing Lungs

by Alysia Li Ying Sawchyn

Burrow Press

“I did want, very badly, an explanation for my destructive behavior,” Alysia Li Ying Sawchyn writes in A Fish Growing Lungs. But what if the explanation is wrong? Sawchyn, who was misdiagnosed with Bipolar I Disorder, understands this danger too well. In this essay collection, she questions what constitutes normal behavior, and how our definitions of “normal” shift according to whom we’re evaluating. She doesn’t ever reach concrete answers, but this seems to be partly the point: concrete, unyielding explanations have, for her, seemed to do more harm than good. Sawchyn prods at these subjects—health, illness, and things that don’t qualify as either—in sharp yet haunting prose. The collection is an interwoven whole, with each subsequent essay shifting readers’ perceptions of what came before. This, too, seems to get at the heart of Sawchyn’s work, provoking us to consider how mental (in)stability is perceived and constructed.

Finalist: Heaven

by Emerson Whitney

McSweeney’s

Heaven, the debut memoir by Emerson Whitney, is a meditation on the body, family, and the language that both restricts and defines us. It is an account of the self, told through compressed moments of personal narrative, critical theory, and psychology, that leaves a reader feeling like they’ve just had a conversation with their smartest, most thoughtful friend.

More than anything, though, Heaven is a story about love: three generations of complicated people navigating all that’s bound to womanhood, while learning to care for one another. Whitney achieves what often feels too difficult to do when writing about family—an honesty born not in spite of love, but because of it.

Finalist: The Meaning of Soul: Black Music and

Resilience since the 1960s

by Emily J. Lordi

Duke University Press

In The Meaning of Soul, Emily J. Lordi focuses her scholarly lens on the history and politics of soul music as it relates to Black empowerment and cultural belonging. The book reads like a backstage pass to events that shaped the sound of resistance and struggle, always guided by Lordi’s historical knowledge and careful observation. Rooted in feminist, queer, and gender theory, Lordi takes a detailed look at the lyrics and performances of popular entertainers like Aretha Franklin and Donny Hathaway to explain how their music was used to uplift, defend, and mobilize. The late critic Phyl Garland, whom Lordi quotes in a chapter on Nina Simone, called the singer a “one-woman summation of musical confluence.” Paraphrasing that quote helps to summarize this book: The Meaning of Soul is a summation of many cultural confluences and how they shaped Black music.

Finalist: Stranger Faces

by Namwali Serpell

Transit Books

What’s in a face? According to Serpell, it means “identity, truth, feeling, beauty, authenticity, humanity.” In this book, her close readings of the face amount to scholarly portraits of people and works as varied as Joseph Merrick, a.k.a. “the Elephant Man,” Hannah Crafts’s The Bondwoman’s Narrative, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, and Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man. She writes of the book, “Stranger Faces probes our mythology of the face by treating it not as an ideal, but as a kind of sign—a symbol, a medium, a piece of language.” Serpell is after what she describes as “the fugitive aspect of the face as art.” Readers will have the feeling of looking, sure, and bearing witness to her theoretical and rhetorical connections. But they will also feel seen, as one does when reading elegant, incisive criticism.

Poetry:

Winner: You Don’t Have to Go to

Mars For Love

by Yona Harvey

Four Way Books

In her latest collection, Yona Harvey pushes the lyric imagination to futuristic boundaries. In conversation with artists like Glenn Ligon, Etta James, and Erykah Badu, and spanning forms ranging from the sonnet to the prose poem to that of the title poem (a long sequence in the form of a “computer-originated audio file” transcript), this book has at its center “the most beautiful dark that hosts the most private sorrows & feeds the hungriest ghosts.” Whether it be back into an unwritten history or toward a freer nation, to the shared experience of other Black women traversing these landscapes, or for readers themselves, You Don’t Have to Go to Mars for Love is a spectacular reaching of love in all its forms.

Finalist: Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry

by John Murillo

Four Way Books

“It ain’t enough to rabble rouse. / To run / off at the mouth,” Murillo writes in “A Refusal to Mourn the Deaths, by Gunfire, of Three Men in Brooklyn.” The entire collection continues to revolve around this tension between poetry (contemporary and otherwise) and the often more visceral violences we try to combat on the page. Questioning poetic traditions such as confessionalism, negative capability, and lyric narrative, and offering variations on themes by other poets like Elizabeth Bishop, Larry Levis, and the Notorious B.I.G., Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry is an exploration of the role and failures of poetry and a brilliantly raging articulation of state-sanctioned modes of violence in the contemporary world.

Finalist: Exclusions

by Noah Falck

Tupelo Press

In Exclusions, Noah Falck builds a hundred different speculative worlds and manages to contain them with intricacy and attention within each poem. The collection is organized around this theme of world-making—each poem is titled after an exclusion, from the expansive, like “Poem Excluding Future,” to the intimate, like “Poem Excluding Happy Hour.” Through these proclamations of exclusions, what is left behind becomes as important as what Falck chooses to fill its stead. In “Poem Excluding Age,” we are given “more stars. More great lakes, more bodies,” and for a collection rooted in absence, this more-ness is abundant in these poems and their imaginative possibilities.

Finalist: Death Industrial Complex

by Candice Wuehle

Action Books

In ekphrastic homage to photographer Francesca Woodman, the poems in Death Industrial Complex lay bare our culture’s obsession with women’s bodies. Sometimes written from the perspective of Woodman herself, and sometimes in conversation with her, the poems zoom in and out of Woodman’s consciousness and act as biography, commentary, and witness all at once. Even as the collection refutes “the petty contours of memoir,” the poems spiral into another kind of documentation—one that is constantly writing, editing, and rewriting the gothic, the dead, and Woodman herself too.

Finalist: Rift Zone

by Tess Taylor

Red Hen Press

In Rift Zone, Tess Taylor deploys language to examine the fragility and fragmentation of our universe. Rooted in Taylor’s hometown in California, which is set along the Hayward fault, these poems portray ruptures both metaphorical and literal, natural and human-caused, universal and personal, historical and in the now. Tackling the haunted histories of gun violence, Japanese internment, and immigration in America, Taylor makes “visible at least in part the unimaginable.” Through analyzing and naming these breaks in American history, Rift Zone also maps a future of rebuilding and realigning toward a new world “emerging at the brink.”

Graphic Narrative:

Winner: Odessa

by Jonathan Hill

Oni Press

With its pink and black ink tones gracefully rendering a ruined version of America, Odessa is both a dystopian graphic novel and a timeless portrayal of youth, love, and independence. Years after a massive earthquake devastates the West Coast, seventeen-year-old Virginia Crane receives a birthday package that sets her and her stowaway younger brothers on a cross-country search for family and meaning. The Vietnamese American siblings navigate broken physical and psychological terrain as they strive to locate a mother they had thought was lost. The illustrations are highly intricate, despite their apparent simplicity, displaying the individual components of architecture, the scars of nature, and the subtle hints of emotion in a face. Odessa carefully explores a novel vision of a post-disaster world, wrought with feeling and sparkling creativity.

Finalist: Shame Pudding: A Graphic Memoir

by Danny Noble

Street Noise

What does it mean to feel at home in one’s family, and then to find a home beyond them? Danny Noble’s debut serves as both a coming-of-age story and a hilarious family portrait. Chronicling the anxiety of her childhood within her vibrant, complicated family and her emergence into a fully formed person, Noble’s panels are small in size but large in personality, populated by funky figures and complicated bonds—most notably, her relationship with her two grandmothers who form the heart of the book. Toward the beginning, a young Noble asks her mother, “How can I be so sure you see what I see?” An older Noble reminds us that it doesn’t matter, that we go on building our own world as we hope to see it.

Finalist: Dancing after TEN

by Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber

Fantagraphics

In the first pages of Dancing after TEN, Vivian Chong writes, “I dedicate this book to my eyes.” In unsparing and harrowing detail, Chong recounts losing her eyesight due to TEN (toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome), briefly regaining it, and then losing it again, this time permanently. A collaboratively drawn project, Dancing after TEN combines Chong’s own drawings during the temporary restoration of her sight with those of her coauthor, Georgia Webber. The result is both a celebration and an elegy, an account of intense suffering and callous cruelty, but also a triumphant commitment to optimism, art-making, and letting go. There is profound loneliness and heartbreak in this book’s darkest pages, which make its last chapters so buoyant they seem to dance off the page.

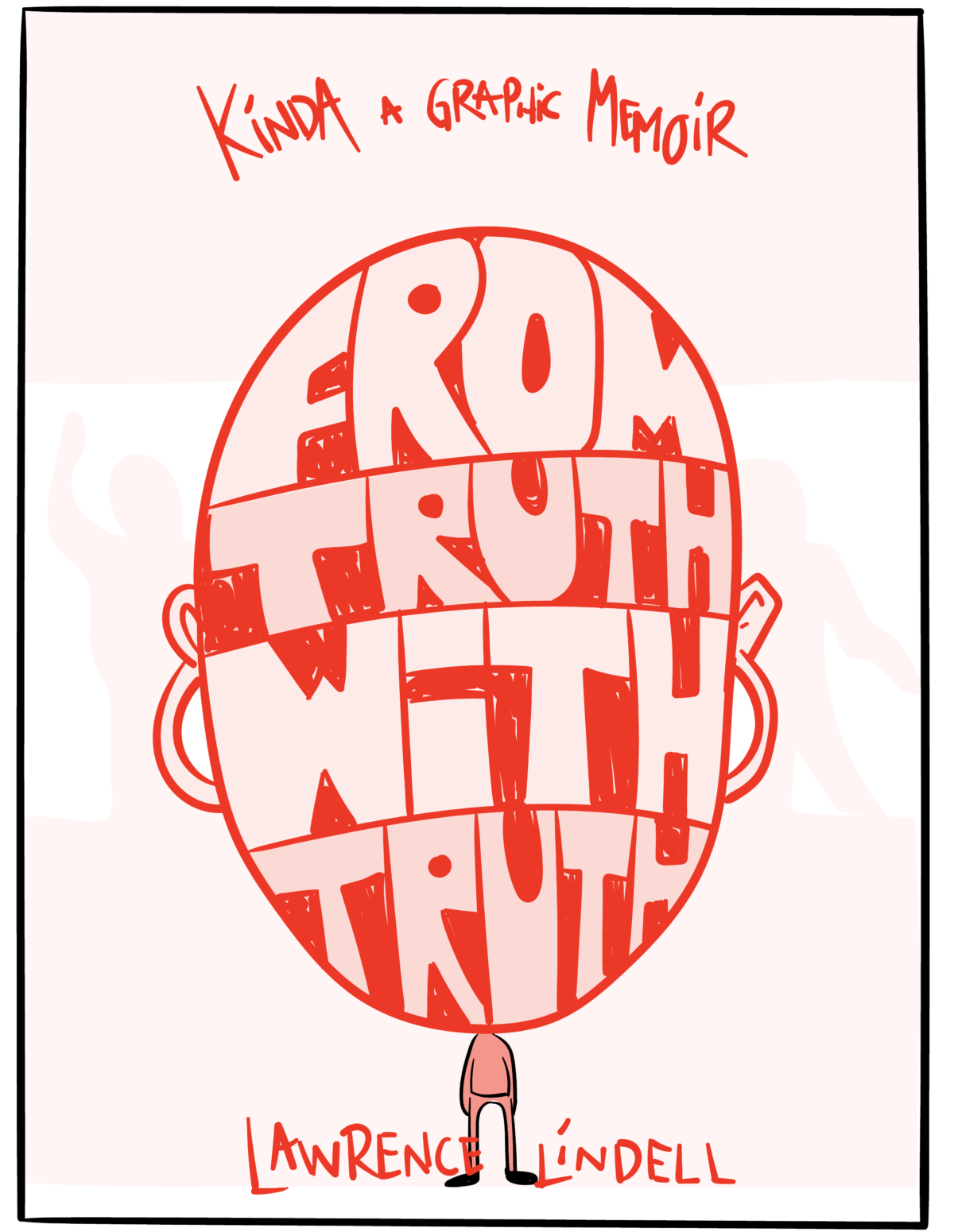

Finalist: From Truth with Truth

by Lawrence Lindell

Self-published

Lawrence Lindell’s zine-like From Truth with Truth tells the story of a life in progress. Through a mix of collage and graphic art, Lindell chronicles his own experience as a queer Black American negotiating faith and mental health challenges. Lindell’s work is warm and unapologetic, tender without being syrupy. The story flashes, in brief glimpses, on the important low points in his life. This scarcity of detail allows the reader to pick up the pen where Lindell leaves off, envisioning his hope and acceptance of a future that is still possible despite the pain of the past. At its heart, From Truth with Truth is an intimate look at what it takes to navigate PTSD and bipolar disorder, and how an artist found healing through the act of making comics.

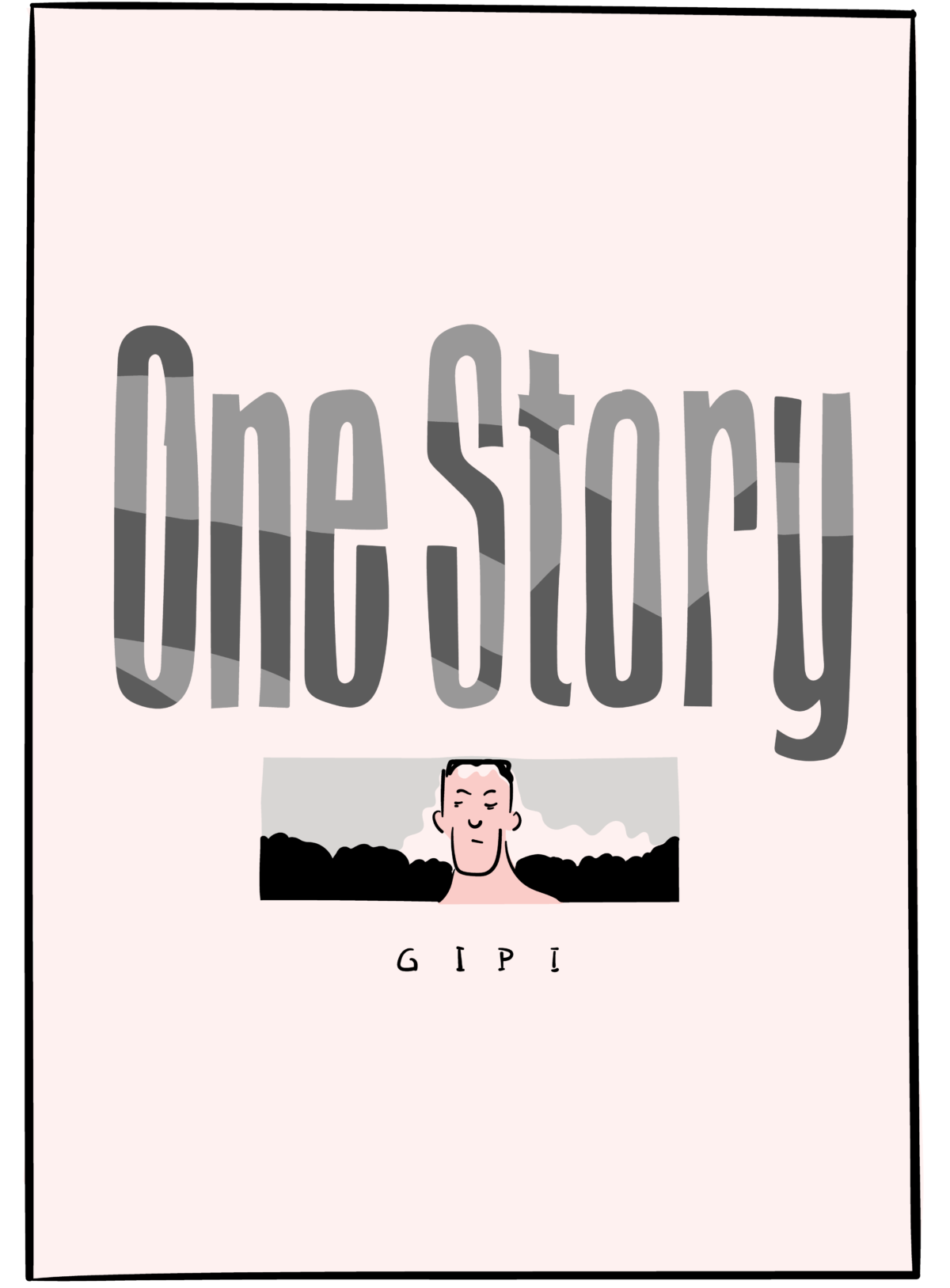

Finalist: One Story

by Gipi (translated by Jaime Richards)

Fantagraphics

A delightfully enigmatic, genuinely haunting entanglement of two parallel stories set generations apart, One Story is an illustrated masterwork. The graphic novel tells the story of Silvano Landi, a successful middle-aged writer who is abandoned by his family, and Landi’s great-grandfather, a World War I soldier experiencing the trauma of combat, before this trauma had a name. From sweepingly cinematic landscapes of wartime to intimate close-ups of characters with ravaged, aging faces, Gipi has created a book that’s heartbreaking in its humanity, offering slivers of hope for characters that have been set adrift in the fury of mental illness and an indifferent world.