Judging by the popularity of the Jurassic Park franchise—five feature films, with a sixth blockbuster scheduled for 2021, three “Lego” Jurassic Park shorts, various theme-park attractions, some forty-six theme-related video games, even a Jurassic Park Crunch Yogurt—dinosaurs (once the province of paleontologists and children) have had a stranglehold on our collective imagination for more than a quarter century. Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel sold more than nine million copies; three years later, the first mega-film, directed by Steven Spielberg, became the second highest-grossing film of all time, earning over $1 billion worldwide.

Though less enormous, less voracious, and lacking dramatic soundtracks to pave their entrances and exits, formidable flesh-and-blood, non-animatronic prehistorics do actually walk among us.

Alligators have been around for some 200 million years, which is 135 million years longer than their dino contemporaries. It wasn’t until the twentieth century that that extraordinary longevity was threatened. Pretty impressive, given all the environmental changes that have ensued in the interim, and the fact that their brains are about the size of a walnut.

Our human ancestors began crafting crude stone tools about 2.5 million years ago.

Biologically, Crocodilia (alligators, crocodiles, caimans, gharials) are closer to birds, dinosaurs to snakes and lizards, but they share a common ancestry. Fossils reveal that back in the day, some alligators grew to nearly forty feet in length, weighing in at 8.5 tons. Simply put, Crocodilia are the closest living examples of the Jurassic’s ancient denizens.

“Dinosaurs and man, two species separated by 65 million years of evolution, have just been suddenly thrown back into the mix together,” notes Jeff Goldblum’s character, Alan Grant, in the 1993 film. “How can we possibly have the slightest idea what to expect?”

In the case of their alligator cousins, it wasn’t just suddenly. Throughout the American south, they’ve always been pretty much unavoidable.

On the big screen, our relationship to Crichton’s creatures is set and predictable. We enjoy the terror they inspire from the dark safety of our upholstered seats. Alligators, in cinema, have always been as dependable in their villainy as Nazis. What better way to dispose of pesky early Christians or enemy Russian spies?

In the real world, the relationship of humans to ancient apex predators is far more complex.

In the mid-19th century, alligator oil was used to lubricate engines and machinery and sometimes recommended as a cure for various ailments; antebellum slaves often relied on alligator meat to supplement otherwise meager diets. But overall, North America’s largest reptile was considered vermin, best suited for target practice, until a Civil War leather shortage led to Confederate troops being decked out in ‘gator boots and saddles; by 1870, those vermin goods had become “fashionable.” From Swamp to Swank. Hatchling to Handbag.

It’s estimated that between 1880 and 1894, in Florida alone, 2.5 million of these “repulsive” creatures were dispatched, their hides salted, rolled up, packed in wooden barrels, and shipped as far afield as Japan. The teeth were carved into buttons, whistles, handles and jewelry, the musk (from lower jaw glands) used in perfumes. Thousands of 6-inch hatchlings were soon being sold as souvenirs.

In 1905, a Smithsonian-subsidized biologist went on a three-week Florida expedition; his days were spent collecting 1,000 goose-egg-sized eggs from nests. His guides spent their evenings hunting some 100 adults with bull’s eye lanterns and shotguns. “It seems a very wanton destruction of life,” Albert M. Reese reported, “especially when it is remembered that a large alligator is worth to the hunter only about $1.50.”

Along with over-harvesting, being caught in fishermen nets, sold as souvenirs, run over on highways and struck by motorized boats on intracoastal rivers, there was mindless cruelty. According to Glen Simmons, who spent his youth hunting gators in Florida’s mangrove swamps long before the Everglades was designated a national park, “more gators were killed for the hell of it than were ever sold”—shot and left to rot, covered with gasoline and set on fire, dynamited out of their nests.

One sotto voce aspect of the ongoing spree was that adult males sport enormous, permanently erect (though usually tucked inside their body) genitalia; in vintage trophy photos, males were sometimes strung up to emphasize the fact. Gator has huge penis. I kill him. Who is the manly male now? Not surprisingly, the appendages were, and are, offered in Asian markets as aphrodisiacs. (A 2016 Bitcoin Forum ad, posted from Borneo, advertised one as both a cure for asthma and “one of the cheapest ways to maintain your marriage.”)

“The alligator has no friends,” noted Field and Stream Magazine in 1913. The demise of the alligator (“with all his ugliness”) was following the demise of Florida’s egrets (“with all their beauty”), their feathers in high demand as hat ornaments. Even those who protested the massive bird slaughter (some of the hunters, themselves, were sickened) had no sympathy for scary swamp bellowers with the temerity to always look like they’re smiling. Before the turn of the century, tourists had already been complaining that gators could no longer be seen in their native habitats. “What would we do for valises and satchels if we had no alligators?” the protagonists worry in The Moving Picture Girls under the Palms; or Lost in the Wilds of Florida, a 1914 childrens’ novel.

Still, in some parts of the country, el lagarto, as the Spanish named them, remained a source of exotic fascination.

The Alligator Hotel, opened in Dalgren, Illinois in 1902, was the place to stay for railroad passengers passing through the heartland. It boasted a large pool of its namesakes (imported from Florida) in the courtyard. When the weather turned cold, the hotel’s owner sequestered them in a storage area under the stairway, occasionally allowing his torpid mascots to warm up in front of the kitchen stove.

Which may or may not have had anything to do with Fats Waller’s charming “Alligator Crawl,” recorded by Louie Armstrong and his Hot Seven in 1927, and later by Waller himself as a piano solo.

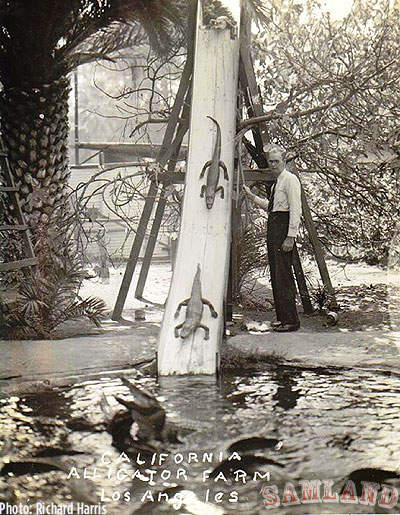

At about the same time, Francis Earnest, a one-time mining camp cook, and his partner, “Alligator” Joe Campbell, loaded the critters bred on their farm—in Arkansas, of all places—onto a train and headed for Hollywood where, for the next several decades, they provided el lagarto actors for “King Solomon’s Mines” (standing in for rapacious African crocodiles), several Tarzan epics (ditto), and more. When not performing on film, the reptiles were coaxed up specially made ladders in order to slide down playground chutes, harnessed to carts, or saddled up so visitors—some 130,000 annually—could “ride” them on a Gator-Go-Round.

Children and adults even fraternized in their swimming holes. Nothing in the public record suggests any damage to life or limb, except perhaps to the alligators that were reincarnated as wallets and luggage in the gift shop.

Some facts:

• Alligators sport 74 to 80 hollow teeth, not for chewing but to pierce, stab and grip. New ones are always growing inside the old ones, an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 in a lifetime.

• There’s evidence that they can orient by the stars, adjusting to shoreline directions when all other possible signals are eliminated.

• Males have six distinct courtship calls; their throat pouch literally vibrates in the water, sending out tiny, concentric infrasonic waves. Some observers have gone so far as to call their mating “tender.”

• The amino acids in their blood are powerful enough to kill some of the most tenacious known bacteria and viruses, including E.Coli, salmonella, dysentery, and one type of HIV. Researchers anticipate that these acids can be used to help prevent infection in burn victims, treat food ulcers in diabetics, and more.

• Highly susceptible to environmental contaminants, they have the potential to help detect DDT, lead, mercury and other toxins in their natural ecosystems and by extension, in humans. Between that and their role in sustaining biological diversity, alligators are coal-mine canaries of wetland vigor.

By the 1930s, taxidermied hatchlings were encircling ashtrays, being decked out in miniature costumes and, with electricity increasingly available, turned into lamp bases—posed holding umbrellas or with lightbulbs in their mouths. Photographer Margaret Bourke-White kept two small gators, Mercury and Mars, on the tiny terrace adjacent to her office on the 61st floor of Manhattan’s Chrysler Building, Florida “souvenirs” from friends. Another pair wandered the halls of the White House, pets of President Hoover’s son, Alan. Passengers flying between the U.S. and South America on Pan Am’s lavish Consolidated Commodores were surrounded by genuine alligator-skin-covered walls.

Farther down the coast,“gatoring” provided Depression-era livelihoods and sustenance for many.

One of the more colorful was Vincent Natulkewicz, a.k.a. “the Wild Man of the Loxahatchee.” A 6’2”, 240 lb. Russian-American with an allegedly checkered past, he arrived on Florida’s Hobe Island in 1930, built a log cabin, boat docks and guest cottages deep in the swamps, roamed bare-chested and barefoot in a military helmet, and trapped gators he displayed in handmade cages.

Over the next couple decades, he became legendary. Rumors swirled of a gargantuan appetite—whole boxes of chocolates, entire pies, cylinders of honey—that extended to women, especially Palm Beach heiresses willing to donate real estate to their backwoods Tarzan.

“Gator hides is worth about two-eighty-five right now for seven foot or better,” notes a character in a 1933 Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings story. (That’s roughly the equivalent of $50 today.) The Pulitzer novelist spent most of her life living in, and writing about, rural Florida. Keeping a far lower profile than Trapper Vince, local woodsman “Mid” Eubanks engaged in “single-handed, thrilling swamp battles” in pursuit of that bounty. According to Popular Science Monthly, Eubanks collected or killed of as many as fifty reptiles a day. He’d been at it for forty years.

In 1935, the reported number of collected Florida hides was 162,000.

As late as the 1940s, one Gainesville brokerage alone was receiving 80,000 annually. Fashion arbiter Vogue Magazine summed up alligator leather—from belts and overnight cases to sling-backs with matching clutches—as “what every well-dressed college student or chic Frenchwoman would wear.”

“Time was,” wrote a naturalist in 1946, “when a thousand gators could be seen around one waterhole in Texas, when the bellowing of hundreds of saurians in the Santee Swamp of South Carolina was as awe-inspiring as the roaring of lions in darkest Africa, when William Bartram, traveling up the St. John’s River in Florida, found that ‘the alligators were in such incredible numbers, and so close together from shore to shore, that it would have been easy to have walked across on their heads.’ Those days are gone.”

“When I was growing up, in the Fifties,” a friend recalled, “we had a stuffed alligator on the mantel. Everyone I knew had one in their house. And that was in Ohio!” Gas stations offered live hatchling “pets” as incentives to customers who said “Fill’er up.” Florida vacationers could even ship them, like oranges, through the mail (complete with care instructions) to blizzard-bound friends up north.

Gator ubiquity was further promoted by 1950s entertainers like Emmett Bejano, a.k.a. The Alligator-Skinned Man, who suffered from a scaly skin disease called ichthyosis. Billed with his wife (a hirsute Puerto Rican a.k.a. Monkey Girl) as “the world’s strangest married couple,” they headlined every leading sideshow in the country, including Ripley’s ‘Believe It or Not’ and Ringling Brothers’ Circus.

And then there was Tuffy Truesdale.

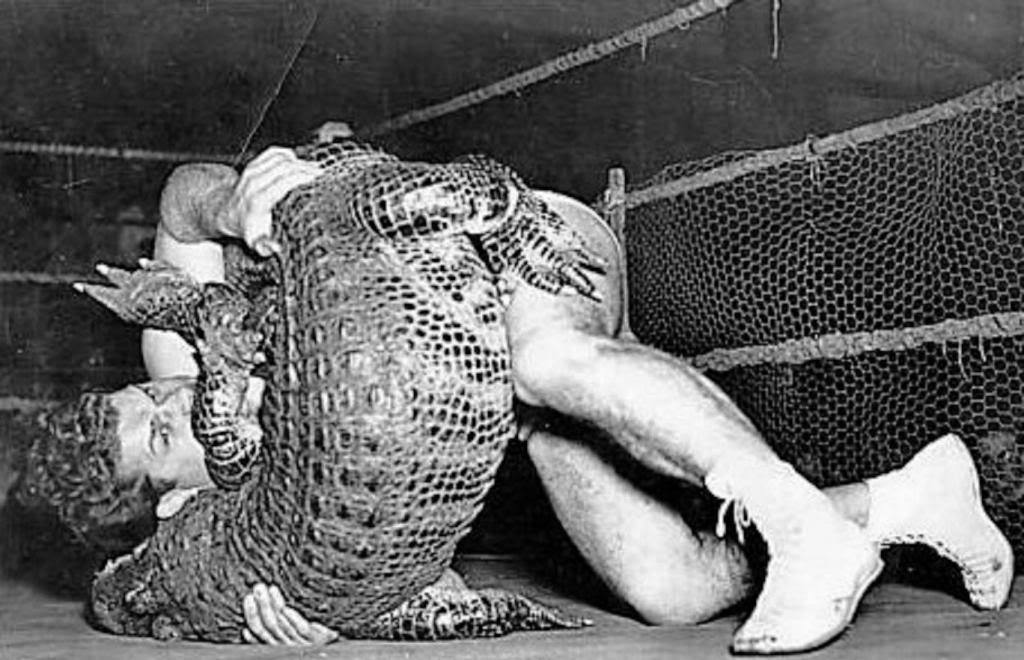

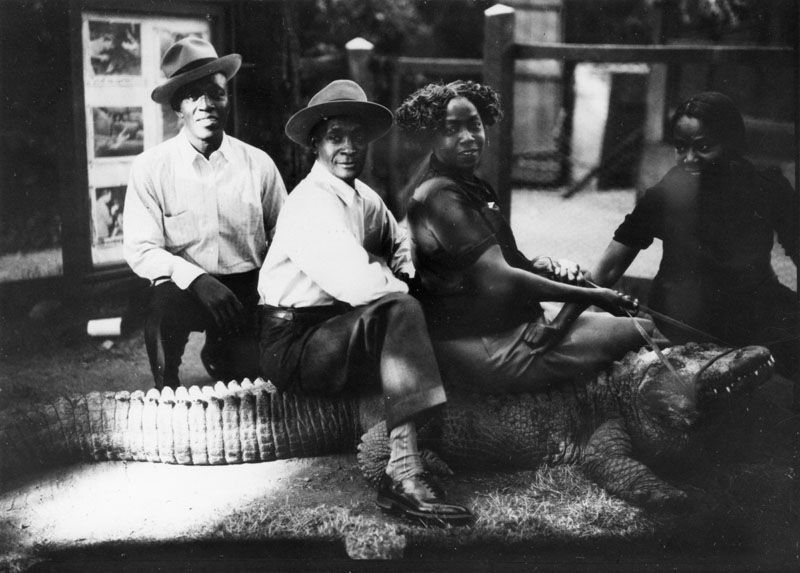

Florida’s Seminoles had learned, early on, that publicly grappling with large, toothy reptiles kept food on the table (though many objected to disrespecting the animals, and themselves, in return for having money literally thrown at them). Now, thanks to the advent of television and more sophisticated marketing techniques, gator wrestling became something of a national craze. Truesdale, a professional middleweight, had discovered that man-handling alligators was more profitable than man-handling men. His performance wardrobe consisted of a blue satin cape with two sequined gators on the front; once onstage, he tossed it dramatically aside to reveal his true working attire—a pair of bathing trunks. One of his specialties was a two-and-a-half roll, which meant that Tuffy was on his back, under the alligator—twice.

When he wasn’t performing on national TV, Truesdale hit the major league sports circuit, touring the country in a remodeled, kerosene-heated bus with three large male gator “opponents” and twenty-six smaller ones, of both sexes, for display.

“Gators have all the advantages,” he explained to a reporter. “They’ve got transparent eyelids.” His favorite sparring partner was Rodney. “Gators are all the same, they got no personality.” But Rodney was different. During the time Truesdale had him, “I must have gone through fifty backup gators. They won’t eat; they don’t care. But Rodney was mean. He would stalk me sometimes. It was great. If alligators were teachable, you would teach them that.” Once, during a performance, Rodney caught Tuffy’s head underwater. Forty stitches. There was also a finger mishap. No hard feelings.

By the late sixties, with more convenient and sanitized offerings like Magic Kingdom and Epcot, the writing was on the wall for Florida’s colorful, often quirky, family-run roadside attractions. Even Miami’s twenty-acre Parrot Jungle (opened in 1936 by an Austrian immigrant) was eventually forced to re-brand itself as a sprawling, pricey, action-adventure park, its “Parrot Circus”—birds pulling chariots, flying a rocket to the moon, riding tiny bicycles along a high wire—replaced with zip lines and the world’s largest inflatable water slide.

Still, enough people these days are interested in experiencing “the real” Florida to support half a dozen alligator-centric eco-tourism venues.

Everglades Holiday Park encompasses twenty-nine acres and welcomes some 300,000 visitors a year. During one of their airboat rides (’”Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity!” Unprecedented access!”), I sat in front of a loquacious, twenty-something blonde and her beau. “Wow, this is just amaaaazing, babe. Awesome. To see them in their natural habitat!”

Red-shouldered hawks and double-breasted cormorants, water lilies and lush sawgrass, iridescent dragonflies, trees heavy with swamp apples, and tropical sunlight glistening on the water like shattered diamonds. The Everglades, it turns out, isn’t a swamp but a shallow, serenely slow-moving river.

“What if we took a trip to the Amazon?!”

“I don’t think you’d like it.”

“But why, babe?”

“Snakes. And mosquitoes.”

Fifteen minutes into the forty-five-minute ride, her interest was flagging. “Do you see anything? I don’t see anything! Where are they?” The airboat’s exceedingly loud, 750-horsepower motor probably wasn’t helping. Plus, I mumbled under my breath, they’re nocturnal.

“Here, gator, gator, gator. Why are they hiding?” she pouted, just as a large pair of eyes and a snout appeared, skimming the water’s surface some five or six yards to our left. “Over there,” I offered. She turned, let out a blood-curdling scream, and flung her arms around her boyfriend’s neck. “Oh my God, he’s so close! I didn’t think he’d be so close!”

Too much reality, not enough Disneyland.

Her counterpart, a thoughtful eleven-year-old visiting with her family from Canada, sat to my right. “I think they’re cute,” she said, “but my sister—she’s a girly girl—thinks they’re gross.” There are a lot of videos about alligators on YouTube, I offered, noticing her iPad. And if you’re feeling really adventurous, there are local restaurants that have them on the menu.

“Americans,” she said solemnly, “kill everything.”

Few are happy to watch these sullen reptiles lolling about, more or less immobile, which is what they mostly do, especially in captivity. We’re primed to expect “an adrenaline-charged good time” in exchange for our entrance, snack and souvenir dollars. The scaly critters can either “do something” or, as one tourist guidebook put it, “go get fat and lazy for Mr. Handbag Machine.”

One way to up the thrill factor is size. In the 1950s, one entrepreneur exhibited Bone Crusher, a 15-footer, billing it “the largest in captivity.” (Bone Crusher was actually a crocodile. It’s an “industry secret” that crocs can grow considerably larger, and are considerably more aggressive, than gators. Today, B.C.’s skull is preserved under glass at Gatorland, a 110-acre Orlando “theme park.”)

Then there’s the tried-and-true feeding frenzy. Start with a pit of hungry animals, then dangle something over them. Gatorland’s “Jumparoo” has visitors line a suspended boardwalk, camcorders and iPhones at the ready. A dinner bell rings and music begins blaring from loud speakers as the gators jockey for position (whose says they’re not trainable?), then leap up four feet or more to nab chicken carcasses that are pulleyed-out above them. As a finale, a lucky tourist gets to dangle his or her very own chicken from a fishing pole.

Other venues take a more genteel approach, using food pellets, saving the chicken to be sold in their snack bars as Gator Bites.

My Everglades airboat ride was followed by a set piece in an enclosed arena bordered by stadium seats. Promoted as showcasing “the impossible and the incredible… the awesome power and voracity of these primitive reptiles,” this “wrestling” demonstration was a far cry from the heyday of Tuffy Truesdale.

After dragging a large, reluctant gator by the tail from his manmade pond onto sand-covered center stage, an attractive young mistress of ceremonies demonstrated the Big Three stunts:

First up, “the Florida Smile.” Our emcee straddled the gator’s back, then coaxed its mouth open to reveal 80 gleaming teeth. The jaws are easy to close: It only takes a finger. But opening them once they’re shut means combating 2,000 pounds of pressure per square inch, more than twice that of lions or tigers. As for the tail, one good swipe can break every bone in your body.

Next, holding the jaws closed, she pulled the neck up toward her, then tucked its closed mouth between her neck and chin and held it there—a trick known as “bulldogging.”

“The Face Off” is a bulldogging variation, this time with the mouth wide open. If one drop of sweat or sand drops down, we’re told—SNAP—it’s all over. Tucking the upper jaw between her chin and chest, our emcee held it there. Then she extended her arms, an image weirdly reminiscent of Christian iconography. After an awkward silence, the less-dazzled-than-hoped-for audience was encouraged to clap.

More facts:

• They’re the only reptile with a four-chambered heart.

• Their retinas reflect light back out, and that glow, after dark, mirrors in the water, a magical effect known as “eyeshine” which, under powerful spotlights, is visible at 400 yards.

• They have excellent hearing and move almost as well on land (even “high walking,” standing almost upright) as in water. They’ve even been known to gallop, clocking in at up to 10 mph.

• Albinos (American alligator genus only) are both rare and short-lived, given sun-sensitive skin and the inability to blend in. Claude is one of the lucky ones. A Florida native, he’s spent the last decade at Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park, where he enjoys rockstar status and his own Facebook page. A weekly scrub down to remove growing algae reveals an elegant, almost surreal porcelain facade.

• Leucistic gators, which look like albinos but have blue eyes and a touch of pigment around the mouth, are rarer still, perhaps as few as twelve in the world.

By the early 1960s, the century-long Florida slaughter count (excluding kills in Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina and Texas) had surpassed ten million.

Concerned that the population was moving irrevocably toward extinction, Florida finally outlawed hunting them. Five years later, in 1967, the feds classified alligators as officially “at risk,” a status they maintained for the next twenty years. The result has been called one of the Endangered Species Act’s greatest success stories.

Predictably, their 1987 removal from “the list” and the lifting of the hunting ban was controversial, one side claiming that (re)turning Florida’s wildlife into a commodity was unconscionable, another that the American alligator was too commercially valuable to ever be safe, yet another that it was about time amateur hunters could get back their God-given recreation rights.

Luxury African safaris can run as high as $3,000 a day, per person; a lottery-issued alligator trapping license/hunting permit can be had for $272 (for Florida residents), $1,022 (non-residents), and a mere $22 for residents already in possession of a Disability Hunting and Fishing License; each is good for two “kills.” New regulations forbid the use of firearms by sports hunters but allow for bows and crossbows, harpoons, spears, spearguns and explosive “bang sticks.”

Their return to the fray did little to discourage poachers, whose methods range from the clever to the comic. Kelby Ouchley, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service veteran who managed gators and their habitats, apprehended one pressure-washing his illegally killed gator in a self-service carwash—at 3 a.m. Then there were the “entrepreneurs” trading baby gators to a pet store in exchange for cocaine. The eggs, alone, can sell for $50 or $60 apiece; the average nest holds thirty-five. In May, 2017, as the result of an ambitious two-year sting operation, nine Floridians were arrested, charged with everything from racketeering and “planting” farm-raised gators in the wild for wealthy hunter clients to “find” to grilling up a federally protected white ibis for lunch. According to one of the accused, a prison-correctional-officer-turned-wildlife-safari-guide, the investigation hadn’t “even scratched the surface of what’s going on.”

Enter nuisance trappers, the guys called in when a gator wanders into an area where it’s considered a threat (backyard, swimming pool, bathing beach, parking lot), something that happens on a regular basis as the human population increasingly commandeers their habitat. Florida has a toll-free Nuisance Hotline. Of the 13,210 calls received in 2017, few claimed the animal in question was acting aggressively; permission was granted for the removal of 8,455. Gators less than four feet in length are relocated to places like the Everglades Holiday Park, though they have an inconvenient habit of returning to their former habitats, even if hundreds of miles away.

Thanks to the popularity of Swamp People (2010), Gator Boys: Alligator Rescue (2012) and Growing Up Gator (2014), all cable TV “reality” series, the number of applications for hunting tags has surged into the thousands. With it came a surge in the demand for alligator meat—zero cholesterol and almost twice the protein of beef—in restaurants throughout the South; between 2013 and 2015, the wholesale price per pound doubled.

Swamp People features the descendants of 18th century French-Canadian refugees who settled in Louisiana’s bayous. This Hemingway-meets-Robinson-Crusoe-meets-John-Wayne-in-the-swamplands saga (lots of facial hair, bleeped-out swear words, shotguns, bitten appendages) has earned a ratings record of seven million viewers, boasted a Times Square billboard, spawned mobile phone app games, and outlived its more recently spawned rivals.

Gator Boys (its human headliners can be found performing at Everglades Holiday Park) carved out a niche as Florida’s only bare-handed nuisance trappers. “I wanted to go the extra mile,” says wrangler and ratings sweepstakes contender Paul, whose wardrobe-of-choice features a bandana-wrapped head and a necklace of impressively large (crocodile?) teeth. In one episode, having put his hand inside a gator’s mouth, he ups the ante by putting his head in. The risk, he explains, isn’t having your skull crushed, it’s having your neck broken.

One successful try is followed by a second.

The jaws snap shut.

Amid the screams of onlookers, Paul somehow manages to disengage; the camera zooms in on large, bleeding puncture wounds dotting both temples. “It’s like having a car door kicked shut on your head,” he calmly explains. (According to a Florida researcher who studies such things, the strength of an alligator’s bite is nearly identical to the jolt one would feel holding a rope, attached to a truck dropped off a building, when the truck reached the rope’s end.) Despite the fact that the “action” took place in murky swamp water, greatly increasing the already strong possibility of infection, Paul stoically refuses a ride to the local hospital. “I’m fine, dude,” he insists, pulling out a bottle of antiseptic. “I’ll have a headache for a couple of days. Been down this road four other times.”

Growing up Gator, which featured a trio of blonde sisters with romance novel names (Britney, Kasey and Chelsey) “who look like they could strut their stuff on a runway,” lasted one season. Picking up the slack, Gator Boys included Ashley and Caroline, two “gator girls,” into their mix.

These so-called living fossils abide in all 67 Florida counties. Statistics put death-by-gator at one-in-a-million odds, considerably lower than dying from a bee sting. The official state count averages ten bites a year, almost all the result of human recklessness.

The 2018 “disappearance” of a Japanese woman last seen walking her dogs along a Florida estuary made the front page of the New York Times. With no human witnesses, it’s impossible to say what, exactly, happened. (Her arm was retrieved, four miles away, from the stomach of an exceptionally large, 12-foot 6-inch gator.) Florida subsequently increased the number of available permits by 1,300 “to reduce the population of this robust, sustainable resource in areas where people and alligators are most likely to come in contact,” a Manifest Destiny rationale that even some non-PETA residents object to.

Pet food manufacturers have reversed the oft-cited notion that chomping down on Rex or Spot is a gator’s idea of Nirvana by incorporating gator meat into their products. “Now your dog’s dream of catching an alligator can come true!” boasts one canine treat company. “Satisfy our dog’s wild side!” says another. There’s even alligator jerky (available with blueberries or sweet potato), a gluten-free, plaque-and breathe-improving version and, from Holland, a green-tinted vegetarian offering shaped like alligators.

In the wake of the reptile’s resurgence, the gator leather trade is, once again, in evidence. It’s also complicated, cut-throat, and notoriously volatile.

In 2008, Louisiana gator farmers, alone, collected over 500,000 eggs in the wild (the nests are spotted by helicopter) for hatching. In 2009, the demand plummeted. Add to that the fact that the industry is increasingly dependent on the whims of European fashion houses, Hermes in particular, that are buying up stateside alligator farms in order to eliminate the middle men (and allegedly hoarding the skins in order to control prices).

Preparing hides is a labor-intensive, twelve-week process; “not properly done,” explains Dave Travers, whose award-winning Sebring Custom Tannery specializes in alligator leather, “the skins can dissolve into glue. Then you just go home and cry.” Travers buys primarily from nuisance trappers. “We’re taking something bad and turning it into something useful,” says Sean Cooper. A former trapper and guide with a background in veterinary medicine, Cooper manages Alligator Jake’s, a top purveyor of exotic leather goods. “And it creates jobs.” The state’s gator population (1.3 million, versus 21 million humans) is regulated and thriving, he adds. Hunt permit fees, some $2 million annually, help fund conservation efforts, and for every nuisance gator that bites the dust in the name of commerce, two hatchlings are released into the wild

Not long ago, the New York Times described the small, tightly knit industry as being made up of “hardy men on the bayou who smoke Camels and drive crumbling pickup trucks, and Paris and New York fashion setters who consider it reasonable to spend $12,000 on an alligator-strap watch.”

Travers, who fits neither of the Times’ smug categories, describes his profession as “a dog-eat-dog business;” Cooper compares it to the Mafia. “If you don’t know someone, you’ll be shut out. And if you do make headway, someone with deep pockets will send people to every boat ramp to pay more for your gators, even if it isn’t cost-effective for them. You’re outdone almost every time.”

Added to that, the state issues a finite number of commercial (versus recreational) harvesting permits for both the reptiles and their eggs. With no term limits, the permits get “locked up” for generations; and those who have them can sell them. As for those who protest that the industry exists at all, they’re the same people, observes Cooper, who “eat big old juicy steaks without knowing where they come from.”

What’s especially notable about the alligator-human equation are its contradictions.

Alligator “products” cover a vertiginous range, from cheap and tacky to prohibitively pricey and chic. A genuine alligator foot keychain or backscratcher (recycled scraps “that would otherwise be thrown away”) can be had for less than $8. Shellac-covered, glass-eyed, open-jawed, taxidermy heads (depending on size) for under $30. Alligator meat (similar to veal with a slight “seafood” edge) is mostly available as “bar food”—fried on a stick – something for frat boys to nibble with their beers. Longtime fast-food purveyor Tarks has upgraded its gator-tail-slathered-in-barbecue-sauce offering to the more health-conscious “gently marinated.”

At the other end of the spectrum, a deep purple, Ralph Lauren alligator tote is available online—secondhand—for $35,000, as is a custom-made, “designer boutique” jacket (reduced from $45K). They pale (figuratively speaking) beside the $100,000, albino-skin-covered, diamond-studded Hermes Birkin bag that soccer star David Beckham bought for his wife in 2008. Which was, in turn, uptowned by another gem-encrusted, Hermes albino bag, auctioned off in 2017 for $379,261. Alligator Jake’s has fulfilled commissions for golf bags, motorcycle seats and dog carriers, a football (for former 49er’s wide receiver Jerry Rice), office furniture, a man’s overcoat, even a caramel-colored piano cover made of 68 skins ($975,000 in 2006). Its owner, a Palm Beach luxury car mogul who doesn’t play a note, just “likes to look at it.”

In today’s world, with elephants being removed from circuses and bulls from bull rings, the proliferation of hatchling souvenirs (both live and stuffed) has been replaced with two-dimensional images and logos on everything from cheap teeshirts to pricey Lacoste sportswear, from golf balls, hand sanitizers and “realistic” baby leg warmers, to energy drinks and football mascots. Twenty-seven states have alligator places names for rivers, highways and more; Florida leads with sixty-three. And where would we be without Bill Haley’s 1958 hit, “See You Later, Alligator, After ‘While, Crocodile”?

What other creature—in the U.S., if not elsewhere—has engendered such a range of professions and lifestyles, from bayou dwellers and poachers to tanners, meat processors and restaurateurs, hunters and farmers to wildlife guides, government protectors and “entertainers,” souvenir makers to haute couture designers?

Not to mention conflicting emotions.

Extolled as an environmental resource and vilified as a blight. Promoted as terrifying and threatening (“Send more tourists. The last one was delicious,” reads one ‘gator teeshirt) and lauded as a key to life-saving medical breakthroughs. Capitalized on as TV and eco-tourism stars and stalked as suburban menaces.

Prehistoric and “modern,” thrown together into the mix. What might we have expected?