When I was eleven, my father had moved from California to Hawaii for work, a distance of approximately 2479 miles. I remember exactly nothing of what we discussed during our scheduled phone date each Sunday morning. My mother worked full-time and late. Until the age of ten, I was charted by various after-school transport programs to the various after-school care centers set up around the city, most often the YMCA or Girls Club. By twelve, in order for my mother to save money, I was taking some form of public transportation each evening to get back home. In short, I was a professional latchkey kid.

Born in 1980 into what has now been coined the “Xennial” micro-generation—in other words I played The Oregon Trail—I arrived at the tail end of the analog childhood and the birth of the helicopter parent, a concept unknown to me until I reached college. I quite literally carried a key on a string, roaming the neighborhood for hours on end until the sun lowered, a hazy amber hued reverie, and I’d return, often entering my home for the first time since I’d left for school that morning. This memory is not intended to hearken to some imagined halcyon days in which everyone wore OshKosh B’gosh and Mr. Rogers was still alive. After all, Los Angeles, the city in which I lived, was embroiled in pain. The ‘92 Riots had ravaged not only the streets but the spirit of the people. Gangs had reached their violent peak. High school students slightly older than me were beginning to walk through metal detectors for the first time, a practice which quickly spread throughout the city, indoctrinating thousands of young people into a system of state-sanctioned violence. It is no wonder the helicopter parent emerged from the miasma of my childhood. Good or bad, I had lots of time to read.

In the ‘80’s and ‘90s, reading was not only important to American youth culture, it was integrated into school curriculums and encouraged almost everywhere. Everyone had LeVar Burton’s Reading Rainbow theme memorized, and the show’s opening credits sequence, which featured a butterfly materializing from an animated oasis of books and color, was sketched permanently in each child’s mind. School days regularly included entire hours devoted to SSR, or Sustained Silent Reading. [Other acronyms for SSR were “Drop Everything and Read (DEAR),” “Free Voluntary Reading (FVR),” or “Uninterrupted Sustained Silent Reading (USSR).”] Most Xenniels and older Millennials remember coming in from recess to find that they had been visited by the Scholastic book fairy. Placed atop their desk was either a small stack of slim glossy paperbacks, or the equally as exciting thin leafy catalogue that listed, along with pictures, all of the books that could be ordered for next month. A week later, we’d return to class with the books desired circled, and the catalogue folded neatly into an envelope also containing a check with our mother or father’s signature. All that happened now was the two-week wait for our bounty.

Long before entire seasons of shows could be devoured in one gleeful, debaucherous night, there existed an often glum and frustrating world where individuals had to pine for the next installment of whatever they might be craving. And if you had to be someplace, or found yourself stuck out of the house without a friend to tape whatever show you had been lecherously desiring, one could feel an entire week’s worth of patience go up in flames. Episodes of TV were not left in some queue awaiting your return at your convenience; rather it was a crap shoot of years if and until that program became syndicated that you could watch it outside of the dedicated weekly distribution schedule. You might one day catch that long-forgotten episode while returning home drunk at two a.m., a slice of pizza folded between a white paper plate, drop your purse on the floor, and with some semblance of joy and awe finally experience what had once seemed so pivotal to your existence.

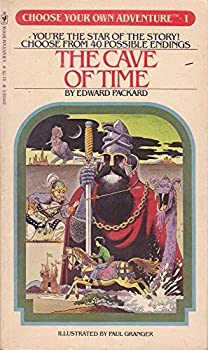

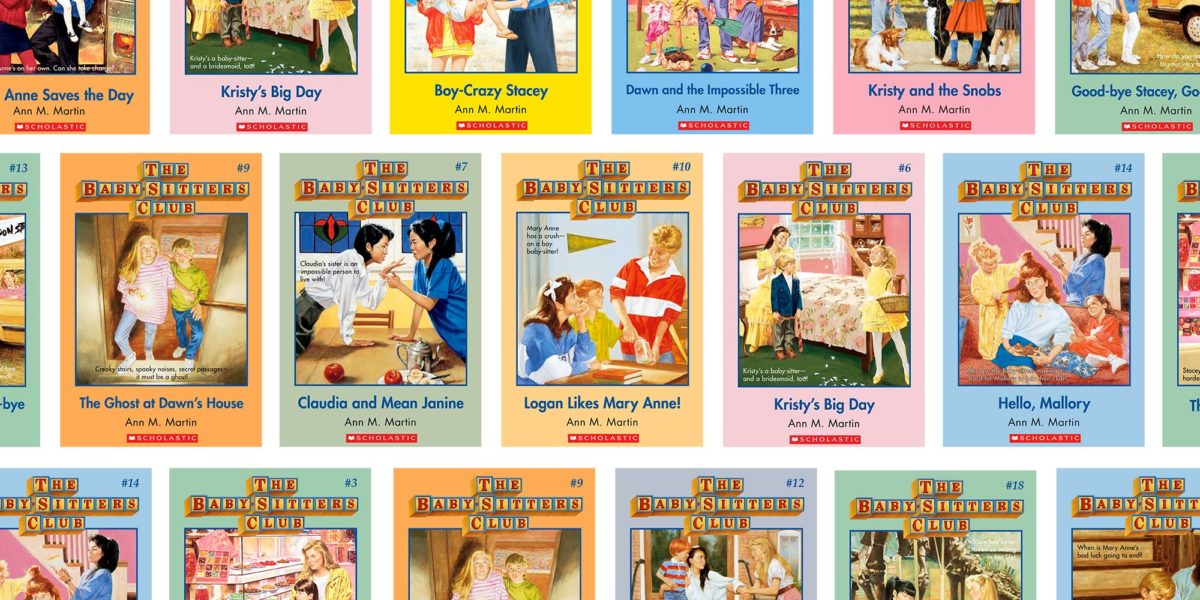

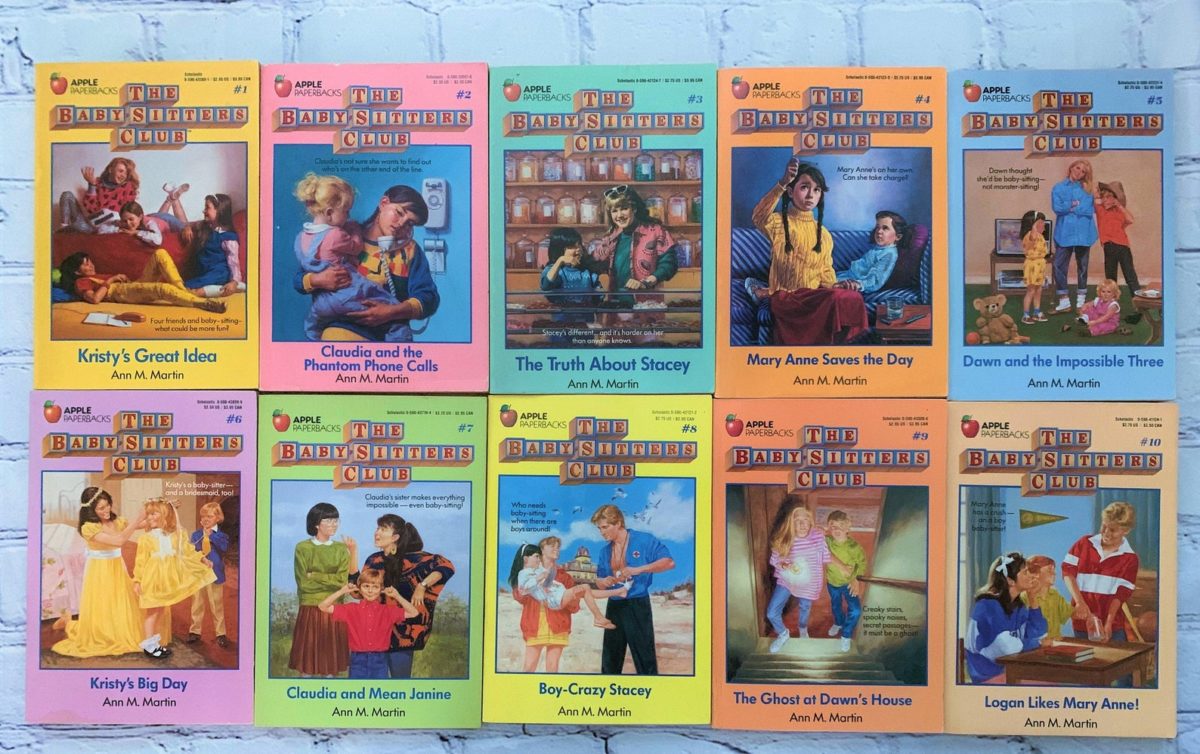

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, reading was an experience that was similar and different in a few ways. On the one hand you had to wait for new installments in a series, but once collected you could binge them. In those olden times, a thing that could be consumed with speed and a junkie’s enthusiasm was the serialized YA novel. Popularized in the 1950s by Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys, the YA serial came into its own in the 1980s. The YA serial, along with the Choose Your Own Adventure series, had swept the youth reading market by storm. Between 1979 and 1999, the Choose Your Own Adventure heyday, the series’s publisher Bantam Books sold more than 250 million copies. Francine Pascal’s Sweet Valley High, Ann M. Martin’s The Baby-Sitters Club, Christopher Pike’s young adult thrillers, R.L. Stine’s Fear Street and lesser-known serials such as Blue Ribbon, Abracadabra, Animal Inn, Camp Sunnyside, Campus Fever, and All That Glitters are just some of the series that sold like hotcakes.

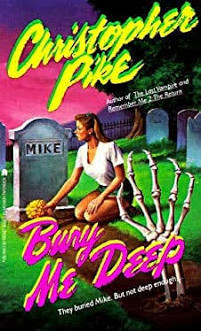

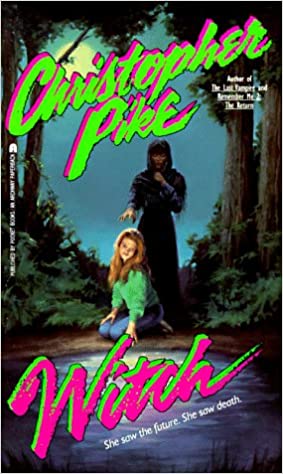

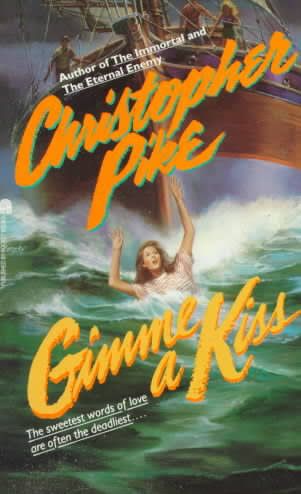

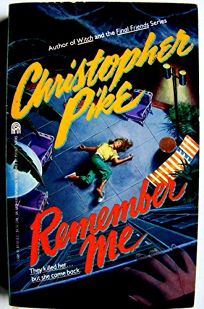

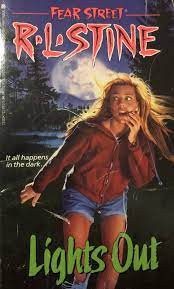

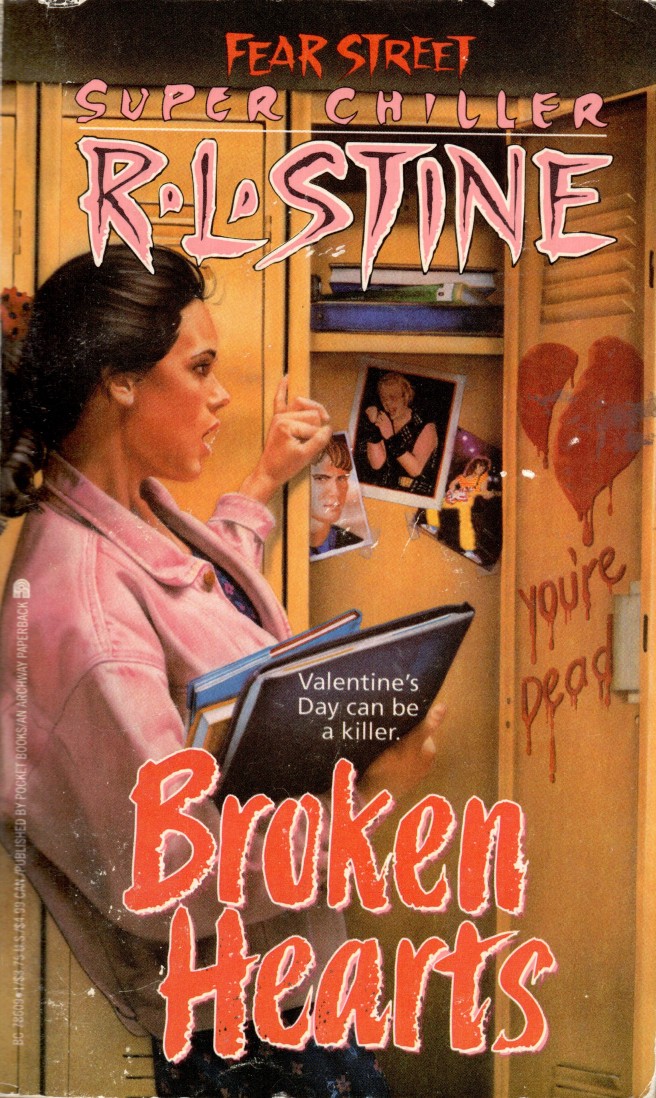

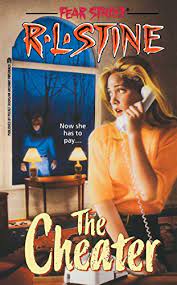

Mostly, I read Christopher Pike and R.L. Stine’s fantastic Fear Street, another series of YA books aimed at the preteen crowd. Having arrived at these series before a burgeoning feminist conciousness, when I did not yet understand that devouring books about dead girls and serial killer boyfriends was perhaps not the most empowering of reads, the characters in Pike’s novels and Fear Street seemed older, more inclined toward risk-taking, sexy. They definitely had sex, even if that notion was not outwardly stated. I imagined they ate Doritos and drank confiscated liquor stolen from a parents’ cabinet. They drove sports cars and told nerds to fuck off. I didn’t want to make money watching bratty babies, I wanted to read about cabin parties in the woods where cheerleaders got their heads sliced off and football players were dead flesh zombies. These were the cool kids as far as this adolescent future alcoholic pothead was concerned. Fear Street‘s covers were adorned with the luscious artwork of ENRIC née Enrique Torres-Prat and Bill Schmidt. Christopher Pike’s similarly enticing cover artwork, most often illustrated by Brian Kotzky, make clear why the books were so popular and readily consumed. The cover art often portrayed teenage girls appearing slightly older than the characters they were meant to portray in the books, screaming into telephones, and viewed through a darkened outside vantage point into a bright window.

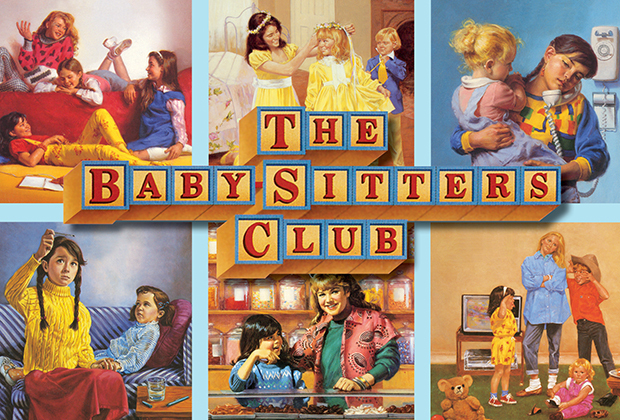

If Christopher Pike’s YA novels were sold out at my local Crown Books, I was faced with the choice of either Sweet Valley High or The Baby-Sitters Club. Then, the choice was clear; I knew the BSC characters. Pike’s first publisher Jean Feiwel, who asked him to write for Scholastic, also first approached Baby-Sitters Club creator Ann M. Martin with the same deal. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, few YA serials were as coveted, collected, and consumed with that jonesing spirit of a late-night Netflix binge than The Baby-Sitters Club. Martin’s serialized adventures of what eventually became eight industrious and responsible preteen girls tapped into the zeitgeist, seizing on the preteen desire for independence while still interrogating the vulnerability of growing up.

Quite the introduction for an essay attempting to review We Are The Baby-Sitters Club (ed. by Marisa Crawford and Megan Milks), a collection of essays and artwork by adult writers honoring the series. It pains me to admit this, but despite the series’s popularity during my childhood I was not much of a BSC fanatic; I was more of an occasional reader. But if one everlasting impression of the series remains, it is that the babysitters themselves, still preteens and left responsible for children even younger, were allowed to meander throughout their neighborhoods late at night, trekking from one home to the next with money in their pockets, no less. Now, in the age of the helicopter parent, it seems shocking that they could have a business to begin with, one that afforded them unsupervised access to income for which their parents trusted they would use wisely. In short, they had lots of freedom, the kind that seems unimaginable today. After reading the arresting and moving collection, I realized that my peers, slightly older and younger, also partook in the pastoral joy of having time to read, for what often seemed, endlessly. While perusing the collection’s essays, it was clear that the authors were my people, weaned in the ‘80s and ‘90s reading climate and perhaps once also possessing a key on a string. Each of the We Are The Baby-Sitters Club contributors seem plucky and precocious, much in the style of the fictionalized girls they pay homage to, their own stories and recollections of youth as consuming and intriguing as any of the nostalgic books and characters they critique.

In fact, the most interesting aspect of We Are the Baby-Sitters Club might be the glimpse it affords its readers into the childhoods of contributors and their experiences as young people, as so few collections deal specifically with this period of life and are almost nonexistent when it comes to the subject of preteen girls. Kristen Arnett’s essay “Fun With Role-Play” immediately caught my attention, as her childhood read as radically different from my own. As I continued reading the essay, Arnett’s own story felt downright fictional. I simply could not imagine it, but then suddenly, as with all good writing, I was transported into the narrative. I was back in time inside Arnett’s church rectory. I became Arnett, rummaging through a box of books, searching for something, anything to read other than bible pamphlets, and to my unexpected joy, stumbling upon a tattered copy of The Baby-Sitters Club, a book I’d been coveting for what seemed like forever. I cared less for Arnett’s observations about Kristy or Mary-Ann and repeatedly wanted to return to her own life: her mother, her library, her church, her town. I was curious and compelled by Arnett’s impending realization of her own queerness. In Yumi Sakugawa’s “Claudia Kishi, My Asian American Female Role Model of the ’90s,” a moving and approachable story told in graphic novel form, I recognized the stories my Asian American friends told me about how they didn’t have an American Girl doll or really any pop-culture figures that looked like them while growing up. And while the Claudia character is of course important, I wanted to stay with Sakugawa, because her observations moved me. Having that kind of connection with a piece of writing is why I read to begin with and I can imagine many other young women devoured books, and specifically The Baby-Sitters Club, for similar reasons.

Many girls read the series for a glimpse into another world, the opportunity to experience the lives of other girls, who for all intents and purposes were viewed by the outside establishment as being all the same. But in the pages of The Baby-Sitters Club it became evident that in fact we could not have been more different.The books seemed to acknowledge and honor the diverse and varying kaleidoscope of experience, socioeconomic, religious, ethnic, sexual, and physical distinctions that exist within young women. We were, as it turned out and had always been, our own people. The magazine and television ads pushing Barbizon Modeling School, lipstick and expensive bras, lotions and shoes, all viewed us as one marketable mass, invested in securing a boyfriend, eradicating zits, and shoving our butts into the latest hottest jeans. In some cases, even the adults closest to us saw us less as individuals and more as average girls all going through more or less the same thing. In reality our desires and identities, problems and interior worlds were and remain so much more developed, layered, and complex.

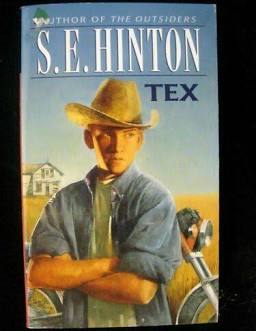

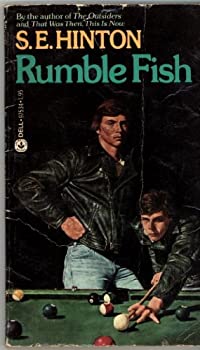

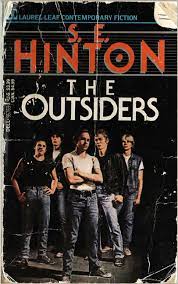

The BSC, Fear Street, and many other YA serials would of course be nowhere without the indulgent and sumptuous world of S.E. Hinton, the all-around undisputed creator of contemporary YA. Hinton took the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys template and turned it on its head, tapping into the very vien that mainlines a preteen’s heart; a feeling of otherness, a desire to belong, and a penchant for melodrama. Her novels The Outsiders, Rumble Fish, and Tex are just a few of the books that while not ostensibly serialized, seem to exist in the same world, much like the fiction set in Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Hinton’s world is one where young boys struggle with toxic masculinity, girls are wild sprinklers aiming to connect, and tenderness and vulnerability pulse on every page. Ann M. Martin and certainly Kristy would most likely wrinkle their nose at such stories; Kristy as I rediscovered is very no nonsense (my friends and I have agreed she is most likely a Capricorn). Regardless, Martin and Kristy owe a great debt to Hinton for whetting the appetite of young readers for stories that both reflect their experience and can be consumed with glee. As Hinton told writer Jon Michaud in a 2014 New Yorker article about her seminal and iconic YA novel The Outsiders, “There was only a handful of books having teen-age protagonists: Mary Jane wants to go to the prom with the football hero and ends up with the boy next door and has a good time anyway. That didn’t ring true to my life. I was surrounded by teens and I couldn’t see anything going on in those books that had anything to do with real life.” Hinton wrote The Outsiders when she was still a teenager, proving that girls contain multitudes.The Baby-Sitters Club understood this.

This is not to say that The Baby-Sitters Club series was written, read, or intended only for teenage girls. We Are the Baby-Sitters Club does a good job of exploring its contributors’ different gender expressions, sexualities, and the various ways the BSC’s young readers entered into these narratives and found identification with the characters, despite having to do a little mental fanfiction puzzle-piecing in order to bend the series’s multiple storylines to fit their own circumstances. Regardless, they felt a belonging on the page that emulated a feeling they could not express otherwise. A good friend recently confided to me that as an adolescent he would check out the Baby-Sitters Club books from the main New York City Public Library branch, carry them out in a knapsack past the festooned lions, through Central Park, until he got home. Then, he’d carefully hide the novels in a globe beside his bed and wait until nightfall to read them, afraid his mother might discover them and by reason of deduction infer his queerness. When he became an adult, his mother, a psychiatrist, confessed that she had found the books almost immediately—the globe was also a lamp—but that out of respect for him she had let them remain hidden.

Other essays explore the things that remain the same despite progress in other areas of the narrative, specifically the very whiteness of the books. Jamie Broadnax’s beautiful and illuminating piece, “Skin the Color of Cocoa”: Colorism and How We See Jessi,” interrogates the cover art used to market and sell the books in comparison with how Jessi, the series’s only Black character, is portrayed on the series covers vs. how she is described within the text itself. The essay touches on an ongoing issue in Hollywood, its refusal to address colorism and cast dark-skinned actresses. This flaw is evident even outside the novels. Although almost universally praised for its diversity, the BSC’s Netflix adaptation (2020) cast a light-skinned Jessi. And even though Mary-Ann is now a mixed-race African American girl, the young actress who plays her can easily pass for white. The consistently funny and brilliant Myriam Gurba takes on bossy pants Kristy and her latent girl-boss capitalism. And much is rightfully written about Claudia Kishi and the remarkable honesty with which the series presented her life and three-dimensionality. Other topics tackled are the BSC’s depiction of ableism, poverty, sexuality, and what is lacking in the series, namely queerness, and the regularity and banality of heteronormativity as presented in the books. More than one writer expresses annoyance and boredom whenever one of the girls, particularly Mary-Ann, has a crush or boyfriend.

Of course Virginia Woolf didn’t specifically have Ann M. Martin in mind when writing the ubiquitous and rightfully acclaimed A Room of One’s Own. As Woolf wrote, the conditions and virtues required in order for talented women to become great writers, on the scale that men had been allowed to achieve are time, money, space, encouragement, and role models. But Martin built on the ideas advanced in that canonical text. Her innovation was to provide reading of one’s own. Martin possessed, and more importantly created, a space for other young women to seek quiet, solace, and ample time to investigate their own interiority. And, as the collection attests, many of her readers are now themselves writers. Woolf’s notion of the room is both a literal and figurative space, and it has always been a stand-in for time.

In 1999, at nineteen, I worked on Sunset Blvd. at Uncle Jer’s, a store that no longer exists. We sold expensive scented candles, hippie dresses, “ethnic” knick knacks, supportive footwear, and turquoise and jade jewelry. I was the youngest employee and often found myself having to converse with old Gen Xers and people of my mother’s generation, namely Boomers. Regularly I was confronted with pop culture references for which I had no clue. One day, one of my disgruntled co-workers, then thirty-two and tired of me switching her Pavement CD for my Daft Punk one in the store’s soundsystem, turned, looked at me, and asked flat out, “How old are you?” “Nineteen,” I replied. Horrified, she stepped back, aghast. What she said next I will never forget: “One day, you too will be old.”

Well, that day has arrived and I find myself drowning in nostalgia while also confounded by and uninterested in things like TikTok and intrigued by a generation of young people who spend hours with their noses pressed into phones. While I’d be lying if I said I was not also addicted to my phone, my brain was wired early on to slug it out through the long weekly patches between things like episodes of my favorite television show. As a result, in addition to building a stash of bookmarks in a pencil case, I developed patience, that most prized of attributes. Patience to deal with things like final chapters that end unresolved, making you wait, breath bated for the Scholastic fairy to return.

Squirreling away to read, rushing home to Claudia Kishi and Stacy McGill with her diabetes and crushes, became the all-enduring goal of a large swath of young people. That space is what Woolf called for, the luxury of time. Jokes aside, I have no more pride in having been born a “Xennial” as I do in being a brunette—it just is what it is—but I do care deeply about the experiences of young people and fear this loss of time, not because these pockets of time no longer exist, but because what is at risk of being lost is the desire to claim these spaces and fill those pockets with books. This would be a good place to mention that until quite recently, as a graduate student I taught entry-level college courses in Freshman Rhetoric and Composition. While I have no official scientific studies to reference, and I anticipate a barrage of readers enthusiastically and astutely letting me know how very wrong I am, I can only speak from experience. When I was teaching, I noticed that a large portion of my students, while gifted and brilliant, had trouble staying focused, specifically during our discussions about whatever we were reading. (And I assigned exciting and tititaling stuff like Jesus’ Son, Persepolis, and John Rechy’s City of Night, a bacchanal of a reading list if ever there was one.) Sharing and immediacy are the currency of the twenty-first century and at forty-one, this world is as much mine as it is my students.’ I work, consume, and operate within it as well, and have a friend who scours TikTok and sends me only the juiciest bits, as I do not trust my addictive personality to ration my time wisely enough to avoid falling down a rabbit hole. But this youthful place, that tree branch, that pillow, long ago cool to the touch, that corner of your world, where you licked a finger and turned a last page and picked up a well-read spine scoured from either a church box or a library shelf only to shove it into a see-through globe. Setting aside an afternoon to read is a fundamental experience of getting older. It’s a marker of a different kind of youth. To lose it, or to not participate in it while able is to lose something that you can never get back, something that for young women and queer nonbinary people, was hard-won and fought for.

As my co-worker predicted, I am now old and have responsibilities that very rarely allow me these long and winding afternoons. Even during the pandemic when we all had “nothing to do,” I found myself swamped, sometimes more exhausted from having been glued to my computer screen for hours on end in Zoom burnout, than I had been before the world stood still. It is the memory of those days, those books, that feeling of ownership, possibility, and the good-fix feeling that the serial provided, that in many ways inspired me and gave me the space to become the writer that I am today. I’m sure the contributors of We Are the Baby-Sitters Club feel much the same way. If Woolf argued passionately for that illustrious room in order to build what did not yet exist, a literature of non-white men, then Ann M. Martin filled it with the stories of that once most rare creature, a preteen girl with time to spare and a worldview of her own.