Format: 354 pp., paperback; Size:5.5″x7.5″; Price:$18; Publisher: Rescue Press; Typeface: Garamond; Book design: Sevy Perez; Mixtapes: One; Sex scenes: Twenty; Representative sentence: “Paul tried for a smile, a look back, an eyeful, a number, some illicit hallway kiss, a blowjob, a romance, a massage, a handjob, a finger up an ass, a free show, a licked lip, a passed note, a present, a surprise, something good, something better than the nothing he had.”

Central Question: Why revisit the queer 90s in 2018?

Except for Titanic and Spice Girls-branded bubblegum, I don’t remember the 90s. Any documents from and about the decade I approach with a scavenging reflex, assembling a kind of pell-mell cultural sensibility in retrospect. Andrea Lawlor’s Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl (Rescue Press, 2017) is about a similar backwards glance, the projective attachments that the novel’s titular Paul brings to the plenitude of culture that surrounds him.

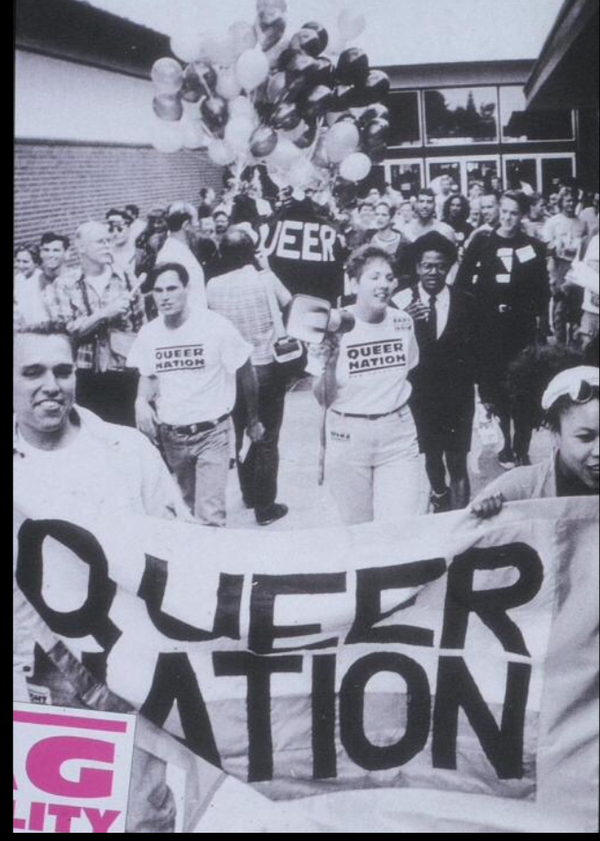

The year’s 1993, the place Iowa City, and the star’s a young 20-something with a voracious appetite. Paul’s secret is he’s a shapeshifter. [1] From Iowa City to Michigan, Provincetown, and San Francisco, he traverses gay and lesbian milieux with a range of embodiments and appetites. “He was an omnivore,” Lawlor writes, “an orange-hankey flagger, an aficionado of all-you-can-eat buffets.” He buses to Chicago to get reamed by a barman with a Tom of Finland package, he shacks up in lesbian puppy love with a vegan Provincetown dyke. Paul’s as avid a participant in late-20th century sexual subcultures as he is a consumer of the music, film, and writing they produced. The result is a headily pornographic historical novel whose quarter-century retrospective doubles as a bracing engagement with just so many cultural events: riot grrl, New Queer Cinema, Chip Delany, check, check, check.

This movement between narrative and retrospection allows Lawlor to glide between the poles of text and metatext, as Robert Glück defined these categories. “The text is the narrative,” Glück writes, while “the metatext is a running analysis, its point of view based on the future.” Metatext “includes the reader, it asks questions, asks for critical response, makes claims on the reader, elicits commitments.” Lawlor entices you to follow Paul’s pornographic adventures from the standpoint of the future, a readerly activity primed to ask questions about historical outcomes and political urgency.

With Lawlor’s novel, Paul is both a character and the name for a textual effect. These two capacities align roughly with text and metatext respectively. Lawlor’s epigraph, from Gertrude Stein’s “Poetry and Grammar,” advises that “people if you like to believe it can be made by their names. Call anybody Paul and they get to be a Paul.” The...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in