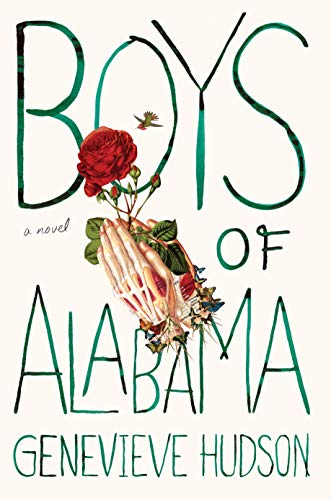

Format: 304 pp., hardcover with dust jacket; Size: 6.5 x 1.1 x 9.6’’; Price: $35.95; Publisher: Liveright Publishing; Number animals the protagonist brings back to life: four (depending on how you count); Number of politicians who double as religious demagogues: one; Other books by the author: Pretend We Live Here, A LIttle in Love With Everyone; Representative Passage: “Max had thought love would begin with a courting ritual: arranged dates, unbuttoned shirts, a first kiss, anticipated yet restrained, on the sidewalk before a house. Love was not a boy in Germany with blood pouring from his mouth. Love was not a witch in Alabama who slept until noon and ate cloves of garlic. But there in that room, Max wanted to buy Pan a house full of flowers.”

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in