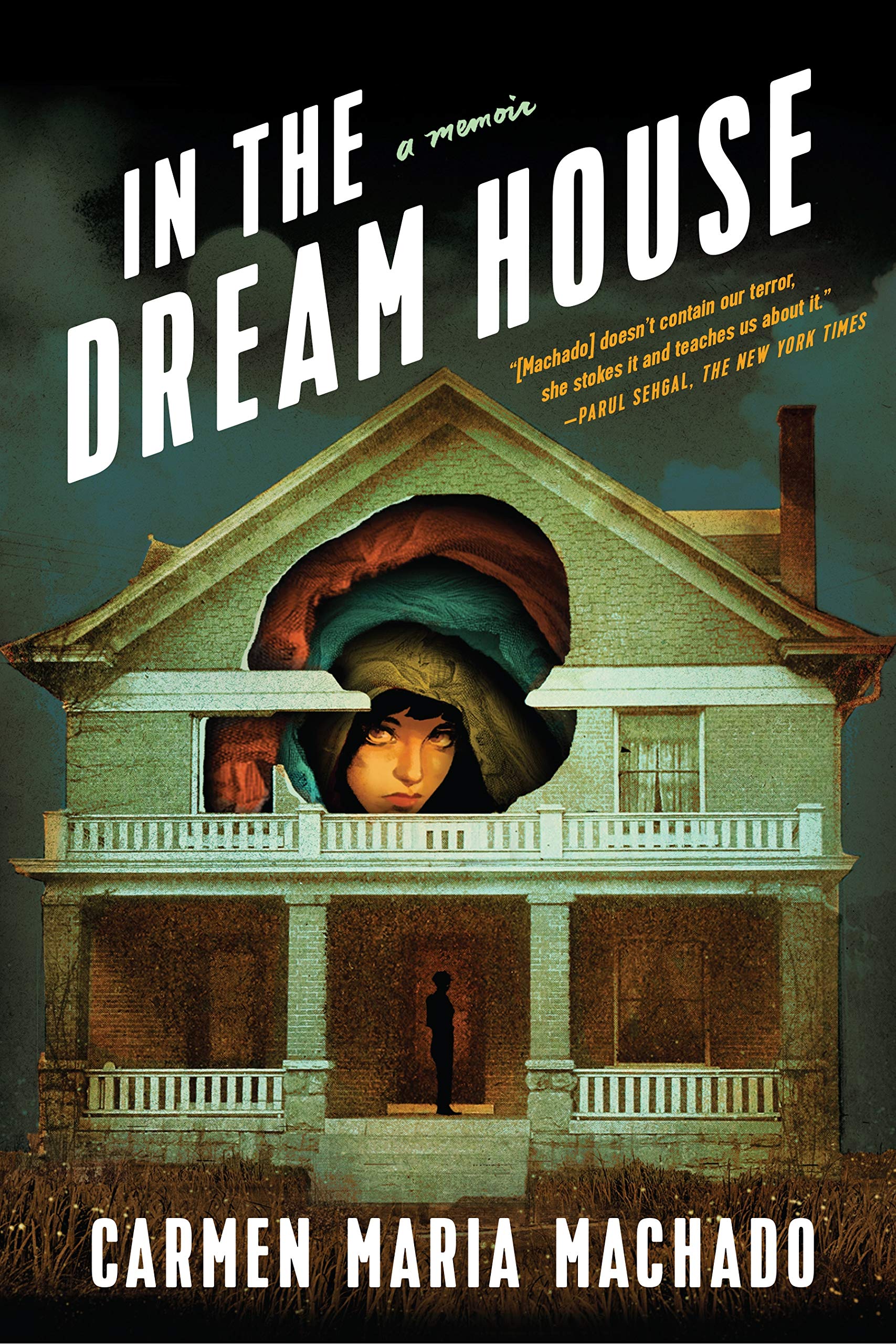

Format: 264 pp., hardcover; Size: 6×9″; Price: $26; Jacket Art: Alex Eckman-Lawn Publisher: Graywolf Number of Dream Houses in The Dream House: 144; Opening Dedication: If you need this book, it is for you; Another book by the author: Her Body and Other Parties; Representative Passage: Dream House as the Wrong Lesson: “ When MGM made the Academy Award-winning version of Gaslight in 1944, they didn’t just remake it. They bought the rights to the 1940 film ‘burned the negative and set out to destroy all existing prints.’ they didn’t succeed, of course—the first film survived. You can still see it. But how strange, how weirdly on the nose. They didn’t just want to reimagine the film; they wanted to eliminate the evidence of the first, as though it had never existed at all.”

Central Question: What is the correlation between the architecture of a house and the infrastructure of traumatic experience?

Sufferers of abuse live according to the logic of a fragmented reality, one that adheres to different rules from linear experience: times contorts, introducing the possibility of winding, repetitive, and cyclical temporality. In her new memoir of life in a psychologically abusive relationship, In the Dream House, Carmen Machado forgoes traditional structure, eliminating standard narrative and refusing to reduce the story to the confines of a single spacetime in order to convey this temporal dislocation. After all, a story that only meets the requirements of a coherent narrative—touching the flagposts of a beginning, middle, and end—would be inept to the task of conveying the true experience of Machado’s past self. Machado charts this erased territory and crafts a retelling of her psychologically abusive relationship with a former romantic partner, a young unnamed woman. The psychological violence employs volatile mechanics: cycles of manipulation and humiliation, narcissistic, and egomaniacal tactics designed to magnify shame and fracture self-love. The two aspiring young writers first meet at a diner in Iowa City, but as their relationship progresses, the dynamic becomes confusing to Machado’s past self. Her confusion stems from the fact that there has been so little language ascribed to romantic abuse in queer relationships. She navigates this often ignored dynamic by re-configuring the memoir form—and her understanding of her own past—so that it adheres to an architecture more accurately attuned to her lived experience.

In The Dream House finds Machado inventing new formal tricks in service to her past self—the memoir’s “you”—and creates a narrative structure that allows her to connect her past and present. We learn about Machado’s splitting in “Dream House as an Exercise in Point of View.” “You were not always just a you,” she remembers. “I was whole—a symbiotic relationship between my best and worst parts—and then, in one sense of the definition, I was cleaved: a neat lop that took first person—that assured confident woman, the girl detective, the adventurer—away from second, who was always anxious and vibrating like a too-small breed of dog.” It’s through these types of experiments that Machado is able to play with a diversity of literary forms, and interrogate her experience through a variety of approaches. Instead of rejecting the categorical labels of genre, Machado embraces them—all of them. The story of her ill-fated relationship—the titular Dream House—shapeshifts as Machado tries to understand her own experience. We encounter it in myriad forms as the book is broken up into genre-specific sections: Dream House as Accident, Dream House as Stoner Comedy, Dream House as Soap Opera, Dream House as Comedy of Errors, Dream House as Queer Villany, Dream House as Star-Crossed Lovers, Dream House as Sci-Fi Thriller. The sections feel scrambled in their arrangement, as if anything could come next; yet the memoir as a whole comes together in a way that tracks intuitively and emotionally.

There are essays that reach into the crevices of fairy tales, film, philosophy, myth, origin, or common belief. In “Dream House as 9 Thorton Square,” Machado investigates the origin of the word “gaslight,” tracing the phrase from the lamp itself, to the Ingrid Bergman movie, to the insidious dynamic of manipulation and denial that leaves its victims questioning their own sanity. “Bergman’s Paula is a terrible double-edged tumble: as she becomes convinced she is forgetful, fragile, and then insane her instability increases. Everything she is, is unmade by her psychological violence: she is radiant, then hysterical, than utterly haunted,” Machado writes. “By the end she is a mere husk, floating around her opulent London residence like a specter.” The essay banks up against more directly personal sections, where the author once again enters the cage of her own confusion, using the facts to explore the compromised reality of her own experience. At one point, she puzzles over the discrepancy between her partner’s words and her actions: “She says she wants to keep you safe. She says she wants to grow old with you. She says she thinks you’re beautiful. She says she thinks you’re sexy. Sometimes when you look at your phone, she has sent you something weirdly ambiguous, and there is a kick of anxiety between your lungs. Sometimes, when you catch her looking at you, you feel like the most scrutinized person in the world.” The memoir’s critical and memoiristic segments rely on one another to draw out the narrative as a whole, which they are able to do not despite their different shapes but because of them. Navigating their arrangement feels frantic and grasping, and the story emerges through its own inability to settle or sit still. Some sections are only a single sentence, while others run for pages. In the Dream House flourishes in its hybridity like a live amorphous goo safe in its petri dish, cellularly shifting so radically that it appears fluid.

The writing feels most tender when Machado addresses her past self in the second person in the sections that follow. You, she calls herself whenever she returns to a scene of a love crime, you walk… you are calm now… you love… The construct is one of clean dissociation, enabling the harsh scenes or memories to be summoned only through the present tense, literally depicting the way that ones painful, confusing or conflicting memories imprint themselves on the present. In these passages, the narrator is constrained by her sensory experience, depersonalized, watching herself exist outside of herself. In a section titled “Dream House as Chekov’s Trigger,” Machado writes, “You slide down to the floor of the bathtub, sobbing, and she walks away. You sit there until the water hitting your body is icy. After a few minutes like that, you reach over and turn the handle to off, shivering. She comes into the bathroom again. When she gets close to you, reaches towards you, you realize she is naked. “ Why are you crying?” She asks in a voice so sweet your voice breaks open like a peach.”

As a reader, I was seduced by what I initially thought was the musicality of these parts, the percussive you / you / you like a bass drum, which had the impact of a hypnosis instructional guiding me through Machado’s waking life dream. But as I read on I realized that the technique allowed me to reverberate alongside the text and its writer in a rare way. Machado grants us access to the way she both speaks and interacts to her subconscious memories, letting us watch her ego-less, excuseless, unapologetic self do something it never thought it might be able to do—exist. She lets herself be confused and pulled in various directions, confronting her own credibility, embracing paradox, watching herself as she gets swung back and forth between love and hurt, love and hurt, love and hurt, often the effect of the swinging proving to be a glueing one, leaving her stuck in a freeze. The sections highlighted the nonverbal underbelly of abuse with such an ease that anyone who has been subjected to psychological trauma will, while reading, easily taste the ghost scent of that freeze.

For me, the relief in witnessing these relivings comes from a writer finally giving something amorphous—the impacts of gaslighting and abuse—a shape. In writing In The Dream House, Machado has confirmed a huge something for a lot for people who, like her, might doubt that abuse ever occurred in the first place. She shows us that we’re not insane. That not only our experience, but the way in which that experience is organized and assembled, is a true and viable reality, as real as anything else, as real of a reality as anybody else’s.