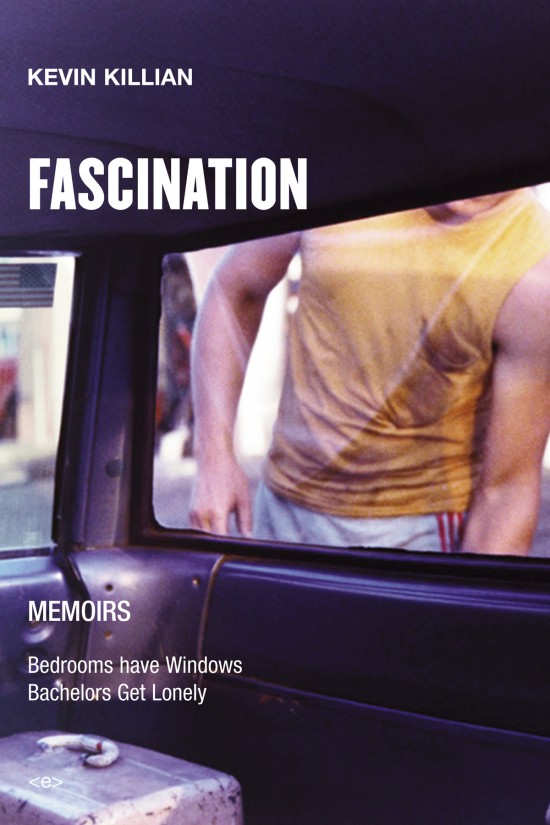

Format: 312 pp., paperback; Size: 7.5″x10″; Price: $16.95; Publisher: Semiotext(e) / Native Agents; Non-exhaustive list of books that have featured a fictionalized Kevin Killian: The Letters of Mina Harker, by Dodie Bellamy (1998), I Hate the Internet, by Jarett Kobek (2016), Martian Dawn and Other Novels (2006), by Michael Friedman; Number of those books in which Kevin Killian is a corpse: one; Representative sentence: “Now there’s no time, and here in San Francisco no seasons, and sex, I now think, is religion with no color—like a bag of liquid on a dead man’s chest.”

Central Question: Do you have to lie to tell the truth?

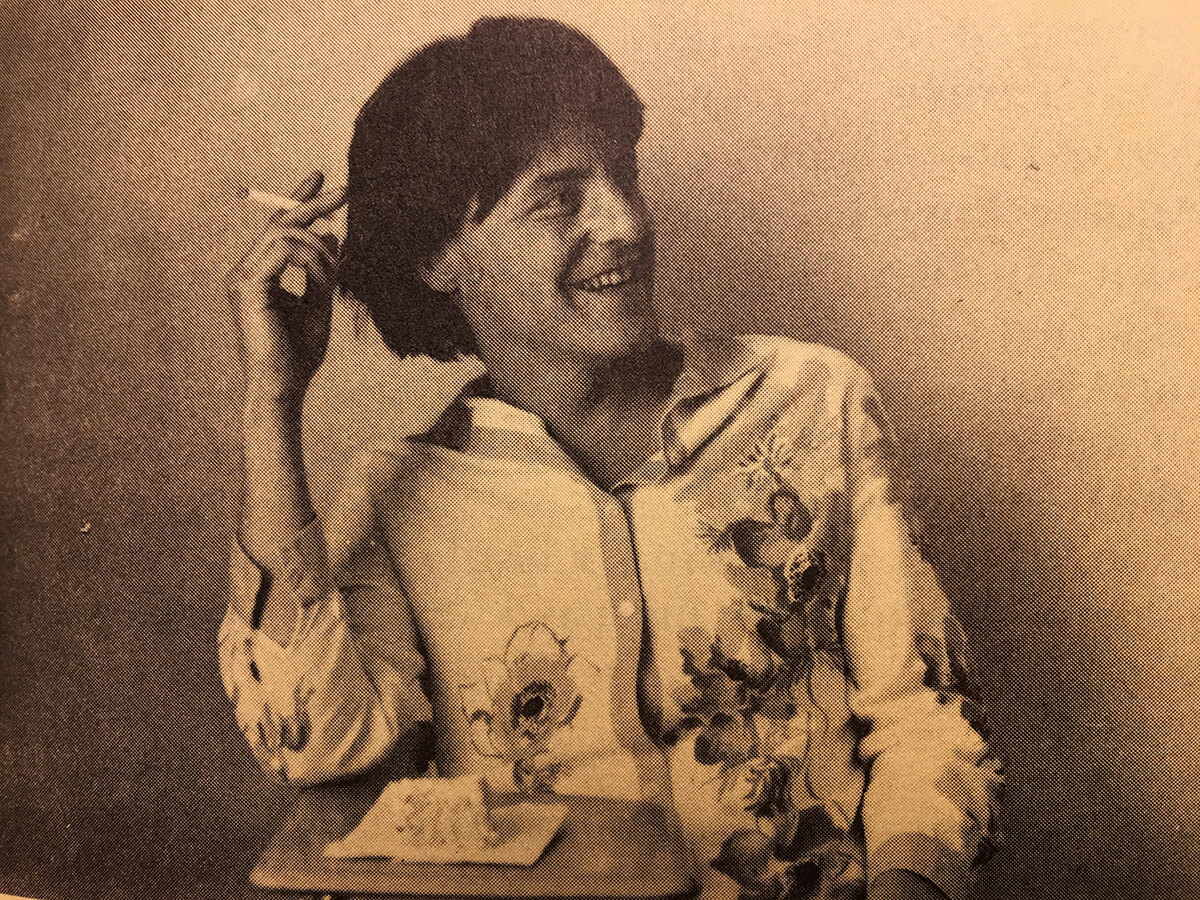

In his new triad of memoirs, Kevin Killian replaces the epiphanic mode of storytelling with something less knowable—a gorgeous turbulence, rather than some dramatic self-discovery. As with Killian’s other writing, informed by the poetics of “New Narrative,” the narrator in Fascination is both uncannily like its author, and someone curiously, entirely, fabulated. The three memoirs that comprise this collection follow Killian through his youthful trespass into that sweet, sticky and sometimes dangerous tunnel between loss and desire—the excesses, heartbreaks, confusions that filled Killian’s world in the 1970s and 1980s. If, as Roland Barthes puts it, in his discussion of the Marquis de Sade, that “Reality and the book are cut apart,” a condition which allows his storytellers to shut themselves away with their harem and to enact their libertinage ad infinitum, then in this set of memoirs, Kevin Killian tests this assumption, by putting into question our faith in the memoirist, he who admits, “I was right and wrong at the same time,” in keeping to the facts of his story. Here, Killian not only disturbs how personalities, in fiction, can be reassembled, but also the ways in which they can be remembered.

The first of the three works here is the long out-of-print Bedrooms Have Windows, originally published by Amethyst Press in 1989—a digressive, sexed-up set of episodes that paints Killian’s world in the 1970s and 1980s as he drives between the suburbs of Long Island and New York City. The narrative moves at the pace of a road movie, and we follow Kevin as he slides between one man’s haunches and the next, shivers alone in jockey shorts, or gets stoned in some yard in the dark. If road movies are supposed to take us to some kind of limit point, in Killian’s account of Long Island, the limit is the very beginning.  We go from A to B to back again, locked in the hell of suburbia just before the first real blow of the AIDS crisis. In this first story, “Loveland,” Killian not only fictionalizes himself—via a-first person narrator, “Kevin,” age 14—he also exaggerates that fabulation with a series of unexpected slights: the mistrust Killian’s narrator has toward his own narrative reliability, an broader ambivalence toward memoir’s generic conventions, and an almost perverse relationship to the inclusion of cultural tokens that all too accurately project the mechanisms of Killian’s desires, as well as our own. “How do I explain further?” Killian asks in “Used To.” “We boys lived in time, in a seething jungle the vines and contours of which, while never as gruesome as, say Vietnam, have now varnished with progress and OPEC and MTV and AIDS.” The goal isn’t to capture life, which he says is too full of “derision and invidiousness,” but perhaps, instead, to watch life as it plays out; “I don’t know life, but video does,” he later admits.

We go from A to B to back again, locked in the hell of suburbia just before the first real blow of the AIDS crisis. In this first story, “Loveland,” Killian not only fictionalizes himself—via a-first person narrator, “Kevin,” age 14—he also exaggerates that fabulation with a series of unexpected slights: the mistrust Killian’s narrator has toward his own narrative reliability, an broader ambivalence toward memoir’s generic conventions, and an almost perverse relationship to the inclusion of cultural tokens that all too accurately project the mechanisms of Killian’s desires, as well as our own. “How do I explain further?” Killian asks in “Used To.” “We boys lived in time, in a seething jungle the vines and contours of which, while never as gruesome as, say Vietnam, have now varnished with progress and OPEC and MTV and AIDS.” The goal isn’t to capture life, which he says is too full of “derision and invidiousness,” but perhaps, instead, to watch life as it plays out; “I don’t know life, but video does,” he later admits.

Killian recounts his teenage years from his Minna Street apartment, where he dreams of being a famous Californian, and in the meantime, learns both to fuck and to write. He recounts his affair with the older Carey who dresses the much younger Kevin up like his own son, Nicky; a personality faked not by the imposition of literary technique but by the twisted perceptual maneuvering enabled by sexual fantasy. Much of Bedrooms finds Kevin with another man, George Grey, the same age as Kevin and also a writer, one who, in another story, writes yet another version of Kevin: “We wrote a ‘book’ together,” George says, “the story of a tormented soul, its growth and development, fated collapse, head transplant with Susan Hayward.” Faking, in this case, is not grounded, but has to take the form of dissociation, of a fated collapse and its inverted retelling (Killian writes Kevin, and not the other way around).Killian deploys the confessional form as a filmmaker might. And the stories in this collection come together as counterfeited pastiche, or as montage. Autobiography is not, in Killian’s prose, a simple telling, but is rather a framework that can be promiscuously, repeatedly retooled. Killian’s interest in film is no secret here. Just as personalities—of Killian’s own, say, or one of his many lovers—become diffuse mixtures of real and fake elements within Fascination’s narrative, so to do the diagetic and non-diagetic elements that compose their world.

There’s a moment in Bedrooms when the narrator puts on George Grey’s voyeuristic eye—as begrudgingly as he does his tight jeans—but only to look back at and judge a younger version of himself:

Once we peered ass-deep in ivy through the slatted wooden blinds of a country cottage. Two men and a women stood naked within … IT was two in the morning in our middle-class suburb, Smithtown. Kevin’s eyes were bugging right out of his head. I envied him his interest in these people, whose bodies weren’t svelte and whose clothes… showed they shopped at the Mall.

The second memoir in Fascination is Bachelors Have Windows, Bedrooms’s planned but never published sequel, parts of which have appeared in subsequent collections of fiction, and in which we continue to follow Killian as he follows through with his spiral, speeding to and from New York high on heavy doses of scotch and Tab. The final memoir here, Triangles in the Sand, also previously unpublished, zeroes in on Killian’s awkward intimacy with experimental cellist Arthur Russell. What’s particularly fascinating about this final narrative, however, is just how dislodged Killian’s account of Russell’s is from our current perception of the closeted virtuoso, lauded by plenty for his contributions to both pop and disco. The Russell Killian paints is an as of yet an unknown acolyte of Allan Ginsberg, his shy accompanist. In this narrative, the longest story within the collection, Russell fights Kevin about what movie to see or music to listen to, can’t, however blushing, Make 1, 2 with Killian (whose hand is down his pants); his cultural credence is deromanticized and we’re given an account of a young man stricken by poverty and trying to make it, who “saw himself as basically straight, straight if weak and prone to stumbling.”

In other words, with Fascination, we get a set of stories that in their digressiveness are, otherwise told straight: historical specificity, here, comes as a process of wandering, of not knowing what’s in front of one’s own eyes, not deciding to move forward but getting there anyway. As Killian writes in his introduction to Writers Who Love Too Much, the recently published anthology of “New Narrative” writing, the small cohort of Bay Area writers of which Killian, along with his partner Dodie Bellamy are co-founders, “I doubt if ‘memoir,’ the word ‘memoir,’ really disguises from the reader, or listener, that something very close to a real event is being described.” Here, the imperative to recount, or to retell reality is different than the one Barthes ascribes to Sade. The radicality, and the necessity of Killian’s Fascination comes from its willingness to yoke those two, reality and the book, together. For a brief moment before Barthes makes his claim about Sade, he pauses in an aside to his reader, and wagers: “Why not test the ‘realism’ of a work by examining not the more or less exact way in which it reproduces reality, but on the contrary the way in which reality could or could not effectuate the novel’s utterance?” Killian makes the same wager, it’s his I’s that make their way through a hell of meanings; eyes that do their very best, and fascinate.