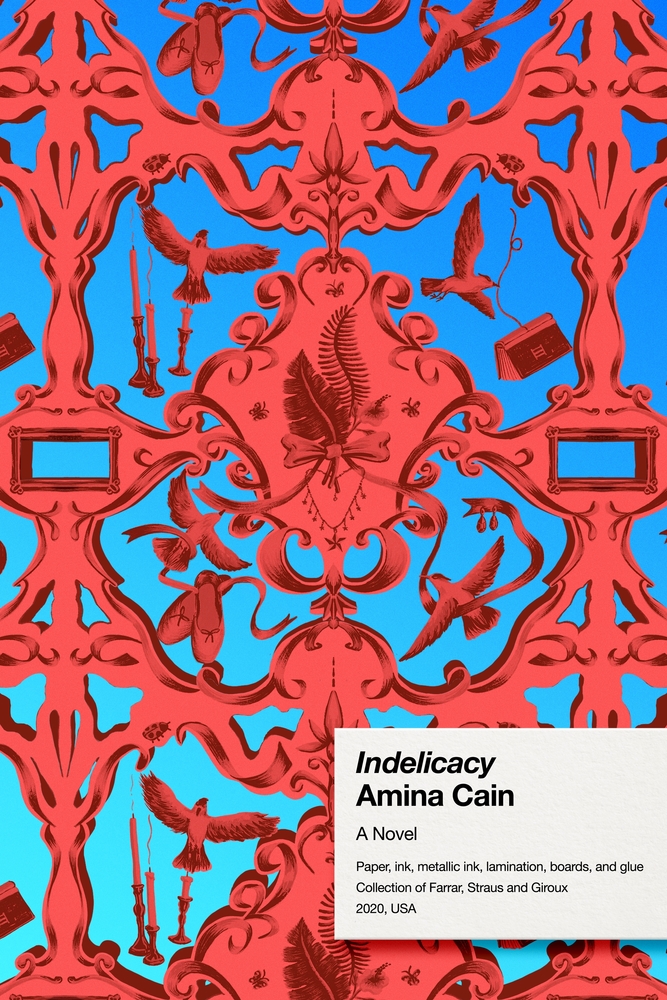

Format: 176 pp., hardcover with dust jacket; Size: 5 X 7.5″; Price: $25; Publisher: Farrar, Straus & Giroux; Number characters named for women in literature: four; Number of times the narrator wonders if her leftovers are worthy of being painted as a still life: one; Other books by the author: I Go To Some Hollow, Creature; Representative Passage: “I was putting on my burgundy dress. Preparing for writing and the walk I would take just after breakfast. Preparing for my own mind. Why did I get so dressed up when no one would see me? It is better that way, to give fancy things to my writing and to my own mind and ramblings, better than wasting them on people I don’t like, and their formal, grand rooms, while it snows outside. All of the fascinations out there, away from where we are sitting.”

Central Question: Is it possible to live a creative life of both freedom and comfort?

In the third part of the 1970s BBC series Ways of Seeing, John Berger focuses on the tradition of the oil painting, claiming that it is a tradition which is more than anything about giving weight to ownership, heft to luxury. Love of art is not, as we assume now in our culture, a neutral or positive virtue, or an expression separate from capitalist consumption. In one of his few counter-examples, Berger chooses a painting by Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance. In it, a woman weighs out objects of wealth, pearls and gold, but Berger insists that she’s in fact weighing out time, moments of precious life itself. What Amina Cain, in her new novel Indelicacy, might disagree with is the assumption that time is not also a commodity. Like cash and treasure, a woman must hoard and consolidate the moments of her life if she wants to use them for herself.

Johannes Vermeer. 1664 – c. 1664

At the outset of Cain’s novel, the protagonist Vitória works as a cleaning woman in a museum. Though her station in life is low, like an escapee from the brother’s Grimm, she takes pleasure in quiet, self-sufficiency and a life far from a glue factory to which she alludes. Vitória scrubs the plain white walls, while at the same time losing herself in the sumptuous surfaces of the paintings she works around. The paintings by Goya, Lorrain, other old masters awaken her creativity and draw her to express her reactions through writing. But as the story moves forward, the images become only one ingredient for the alchemy of artistic discipline.

Cain intersperses the narration with Vitória’s descriptions of the paintings, which are plainspoken and often end in gentle projections like “I wonder what it feels like” or, about a portrait of a landed aristocrat, “I want France behind me too.” When Vitória writes about the paintings, she yearns for nice things like the jewelry and fine clothes that she sees in them, on the museumgoers, in shop windows. When suddenly, with barely a fairytale gloss of the logistics of their meeting, a rich man appears in the museum cloakroom to marry her, she slips easily into luxurious new surroundings. The furniture is substantial, a maid is there gives the gift of time. Her husband suggests encouragingly that since she has been working since the age of twelve, she “deserves to get bored.”

Normally, when fictional women dream themselves into houses and situations beyond their means, there are strings attached. Or at least ghosts. In Rebecca, the house of Manderley itself rejects the protagonist. The narrator of Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber is nearly murdered for moving freely through her new castle. Even in Elizabeth Taylor’s more realistic Angel, the titular character becomes a pariah in her desire for the estate where her aunt works as a maid. By the time she owns it she is nearly deformed by her desire. For Vitória, though, her movement through her new life and house is nearly seamless. She has pleasant sex, enjoys her creature comforts, uses her free time for her mind. Expectations and limits are easily dodged. And she does not get bored. The husband neither encourages or discourages her writing.

In fact the husband speaks few words, and Vitória’s life remains lived inside her own mind and among the women around her. She finds a friend, Dana, who accompanies her to the ballet and is as serious about dance as Vitória is about writing. She reconnects with Antoinette, her fellow museum worker, who married poor but for love. She tries to befriend her maid Solange.

Cain, like her protagonist, weaves a network of women who fascinate her. All four of the women above are named for the characters in the works of Cain’s heros. Their namesakes hail from Clarice Lispector, Octavia Butler, Jean Rhys, and the gender transgressive world of Jean Genet. Rather than leaning on specific references, Cain gestures towards a gallery of her inspirations, as though she sketched studies of each canonical character before breathing life into her own distinct creations. On one breathless page where Cain puts them all together, the narrator glimpses each character in her novel of origin, calling these stories their past lives.

These reincarnations are not merely about writerly legacy. For Cain, the concept of past lives is far richer idea than literary allusion, and Buddhist thought informs her work. In her previous book, Creature, Cain’s characters attend a silent retreat, they try to read “The Flower Ornament Scripture.” In both books, the prose itself feels like a retreat, spare and clean. A great mirror of a lake appears again and again at the center of a town which feels Swiss in its salubrious neutrality.

When Vitória takes up ballet, the quintessentially western bodily discipline, she compares it to her cleaning—a physical pursuit that represents a third sphere, different from the leisure of sitting and walking around which her new life revolves. In that moment, ballet and cleaning are not respectively pleasure and chore, but both things she takes on in the meditative spirit of yoga or tai chi. They are invisible work. She says her mind is at ease during her dance classes.

Cain is particularly interested in exploring this space of ease between the body and the mind, in figuring out how a creature of comfort can also be a creature who creates. One subtle way in which Cain explores this split between the agency is that until about two thirds of the way through the book, we do not know Vitória’s name. The scene when we discover that she is called Vitória arrives when she first meets the newborn of her friend Antoinette, and in confronting reproduction we realize her unspoken success and power. Vitória has been victorious in suppressing pregnancy, and therefore her husband’s will, victorious over the body. She has nurtured her writing, and chosen work which is invisible to her husband rather than something concrete—a baby—which blindly fulfills the marital pact.

Just as Vitória doubts the pomp of baptizing the baby when she talks to Antoinette, she is also full of doubts about ceremony surrounding her own writing. She hopes she is writing a book, but she wonders also whether she is producing something more like a “commonplace book,” or a garbage “dump.” She dresses like a writer to attend her first literary reading, but she hates the arrogant men in conversation. She calls them “worms,” just as she called her old boss a “hairy tooth,” and a man who interrupted her writing “the butt of a wolf.”

These funny, clumsy insults show Cain’s great skill at changing register in an otherwise spare, earnest story. But as far as Vitória is concerned, the weird jabs show a retreat into self more than a combativeness toward the world. Likewise, when she tries to conspire with her maid Solange to make a peaceful transfer of her husband from one wife (herself) to another (a maid, equal and interchangeable with herself, at least in her husband’s eyes), it shows she has a deep interest in keeping serenity around herself. Only by making the fewest waves possible is she able to slip into herself and write. And only by treading carefully is she able to keep her comfort and her freedom.

Her husband senses this quiet, instinctive offense—one day after sex he tells her she is like an animal, testing it as insult and compliment. But it is neither insult nor compliment to our narrator—it is what she most wants, to live more like an animal. In her writing, she muses on stray dogs who “have all their freedom but not enough comfort.” When she makes her escape to the country, not just parting from the structure of her husband’s household, but from the framework of the paintings, the commodity that first acted as conduit for her art. She wants to make her own paintings with words, from life and nature and empty space rather than someone else’s template. “If I’m bored, at least it’s not coming from outside my own life. I choose the boredom that I’m a part of.” Likewise, for her art she chooses not the things that she can own, but space and time she can inhabit.

Though Cain sets her book in an implied 18th century, the total effect calls to mind the spaceless and sumptuous red plains of La Dame à la licorne, a series of medieval tapestries at Paris’s Cluny Museum. In this anonymous work, a woman finds herself in allegorical conversation with the five senses. Fountains, music, exotic beasts, lush fruits. There is a sixth sense represented, too, in which the woman opens a casket of jewelry. The sense at hand here appears to be an aesthetic reaction, the unique delight humans feel when encountering a piece of artistry, a finely wrought object.

Because Vitória refuses “to be a domestic first and shallow vessel out and about in the world,” she carves a space for herself in which she reacts as neither caretaker nor owner of the beauty around her. She doesn’t dust or hoard; she savors and considers. The success of Cain’s book lies in this distance, in the solemn joy of meeting the material world on one’s own terms. Consider the range of emotions that can couple with curiosity, or the feelings one has in a quiet gallery. The spectrum is huge, but quiet and rarely evident to a bystander. Indelicacy is a quiet stalking of inspiration, a very delicate approach to these meetings.