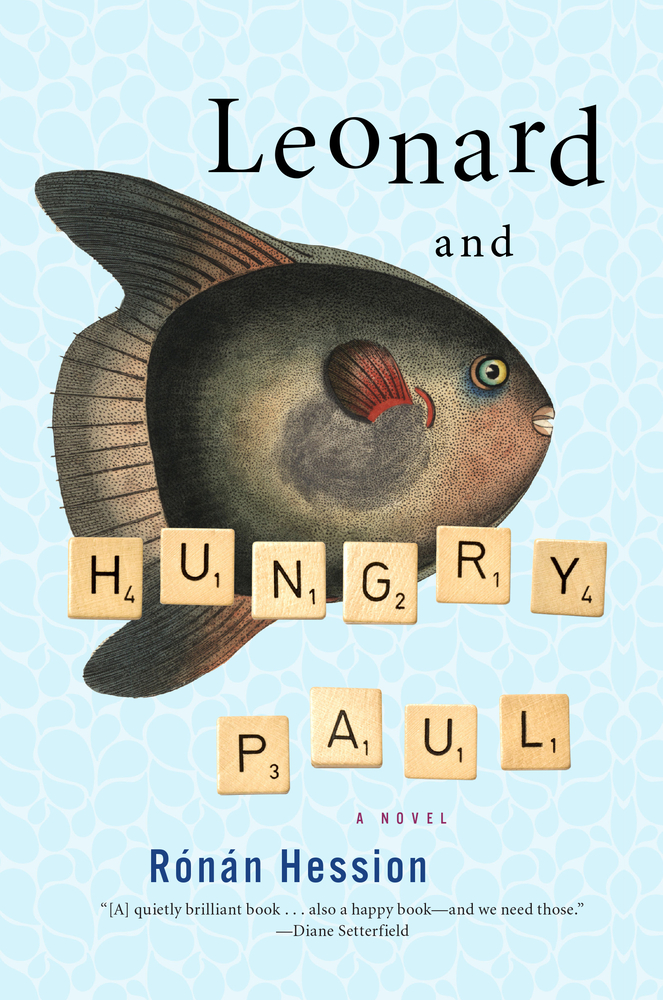

Format: 256 pp., hardcover; Size: 5.5” x 8.3”; Price: $25.99; Publisher: Melville House and Bluemoose Press; Other books by the author: Panenka, coming soon; Board Games Played: At least six; Explanations for why he’s called Hungry Paul: Zero; Representative Passage: “Though she didn’t say so, he realised that she had picked the sunfish as her favourite because she knew nobody else would pick it. It would have pained her beautiful heart to think that there was a living thing that would go through life unloved and she was compensating for that with a special, deliberate effort to love it.”

Central Question: What are the mechanics of happiness?

Last April, I tweeted “i want to read a book where only nice and gentle things happen to good and loving people. idgaf if it’s boring.” I had grown so tired of plots that make characters suffer in order to sink hooks of anxiety into the meat of my attention. I had “what will happen next” apprehension fatigue. So many books that have risen to critical attention over the last four years have reflected ambient cultural dread, drawing their narrative momentum from the abundant wells of anxiety and foreboding; it seems that our understanding of plot depends on these emotions as the basis of the narrative arc. Even the most feel-good novels depend on things turning out alright in the end without being alright all along, and that wasn’t quite what I wanted. I wanted a book that relished happiness and contentment on their own merit, not just because they were under threat from an imminent plot twist, or were a reward for weathering one. But could such a book as the one I craved actually exist? What would it even look like?

It might look like Ronan Hession’s Leonard and Hungry Paul, which has already gained a cult following in the UK and was recently released in the US by Melville House. We’ve become accustomed to works that comment upon the current climate by reflecting day-to-day life as something alienating or menacing. In contrast, Leonard and Hungry Paul asks us to recognize what is good in the world when we see it; to find and appreciate the people who are good to us in big ways and small; to grow from our mistakes and misapprehensions so that we can continue caring for our communities in the most effectively loving ways possible. By depicting “overlooked people who had simply lived their lives as best they could” as worthy of close attention, it magnifies the smallest details and quietest moments of daily life without distorting them or making them exaggerated grotesqueries. In doing so, it challenges assumptions about what emotions are required to drive a story, and offers an alternative to dread-laden narratives, leaning into mundanity and familiarity in order to indict the inhumane cacophony of the present. To read Leonard and Hungry Paul is to encounter a manifesto of community-building: it makes an impassioned argument for the merit of gentleness, delight, and mutual support in a world that wants us to contort ourselves into the unfeeling shapes capitalism demands.

Hession’s protagonist is Leonard, an observant children’s encyclopedia writer who is “interested in pretty much everything”, with a particular knack for conveying the sorts of details kids appreciate, like asides about the day-to-day lives of historical children and language like “frogmarch” or “eyeballing.” His best friend Hungry Paul is a part-time volunteer postman still living in his childhood bedroom at home who, to the chagrin of his elder sister Grace, has displayed little interest in leaving the nest. However, as soon as the character is introduced, Hession notes that Hungry Paul “never left home because his family was a happy one, and maybe it’s rarer than it ought to be that a person appreciates such things.” These two friends have their families, each other, a shared love of board games, and companionable silence. Though their social awkwardness and indifference to the landmarks of adulthood (relationships, domestic and financial independence, or professional momentum) strike their acquaintances as benignly odd, these two men are content. However, after the death of his mother, Leonard finds himself increasingly stifled by his life’s loneliness. “I just can’t help feeling that I need to open the doors and windows of my life a little,” he tells Paul. Over the course of the book, they use their attentiveness to the rhythms of conversation and silence to deepen their relationships with one another, their families, and those around them. Leonard meets Shelly, a cute coworker who appreciates the encyclopedias he ghostwrites before she even knows they’re his work. Inspired by her admiration, he begins his first project writing under his own name. Hungry Paul, on the other hand, helps his family prepare for Grace’s wedding, and in doing so begins to wonder whether it might be his turn to leave the proverbial nest.

On its surface, this novel is a story about its characters finding love and finding purpose, about the nature of independence and interdependence. As the story unfolds, however, we encounter an unexpected narrative model that doesn’t treat tension as integral to rising action. Since the happiness of its characters is never in question, we never wonder whether things will end up alright. Instead the novel devotes the majority of its attention to the processes of resolution and de-escalation. In Leonard and Hungry Paul, conflict and rising action takes the form of tactful conversations between friends, lovers, and family who are all listened to and considered and taken to heart. Likewise, rather than prioritizing the extremes of romantic passion, Hession’s love story plotline depicts a deep, measured consideration of what constitutes care and compatibility. As mistakes are made and consequences encountered, the focus is on how these fundamentally good people can become better at being good to each other. The novel asks: how do we give each other what we need, and how does compassion shapeshift in order to sustain the care between people over the course of a lifetime?

In this way, Leonard and Hungry Paul is distinct from the so-called “uplit” trend of a couple years ago, the way that goodness is distinguished from mere niceness. In a sonnet about activism and aid, Edna St. Vincent Millay declares that “we contrive / lean comfort for the starving, who intrude / upon them with our pots of pity,” and such pity is often an unspoken premise of literature that claims to uplift. “Uplit” may claim to extend sympathy to its characters, but such sympathy cannot mitigate the anguish it inflicts upon its characters to precipitate story, or to outrun the pity the plot has demanded from readers at every turn. Instead of the self-congratulatory mercy of a hard-earned happy ending, Leonard and Hungry Paul makes joy the meal rather than the dessert. What are the mechanics of happiness, up close and personal? As both Leonard and Hungry Paul find love, fulfillment, and situate themselves in a version of independence that actually brings them closer to their friends and family, happiness is the premise rather than the reward, and it is continually held up to the light and scrutinized as something the characters build and make, rather than something unexamined that simply lands in their laps.

Because it persistently refuses to condescend to its characters as they do the work of loving each other, Leonard and Hungry Paul is no meager pot of pity—because, as the next line of Millay’s sonnet says, “brewed / from stronger meat must be the broth we give.” This story challenges any assumption that these awkward-but-sweet hearted protagonists are to be pitied or fixed, even by those doing so from a place of loving concern. As the novel acknowledges, “When you love somebody it can be hard to know where the boundary of solicitude ends and interference begins” and there is value to care that exists as support rather than improvement. In this way, Grace—the self-appointed “family superhero”—acts as a kind of stand-in for the reader, who wants to exercise overbearing concern for the protagonists. The book instead offers something that liberates Leonard, Hungry Paul, Grace, and the reader from the pressure of expectation, because Grace’s intrusions are consistently, gently rebutted, both in-scene by other characters and more broadly by the plot’s structure. For example, it would have been hypocritical to shape Grace, who believes she must “solve” the problem of Hungry Paul, into a problem herself to be solved. The book models support and cooperation rather than such presumption, and doesn’t succumb to the easy arrangement that would’ve turned Grace into an antagonist. In this novel’s vision of kindness, there is room both for making mistakes, and also for making them better oneself. Rather than requiring her to be either unlikable or humiliated to highlight the error of her ways, Hession extends Grace—well, grace:

“Whatever duty you have imposed on yourself towards me, I now absolve you from it. I love you, but I don’t need you to look after me. I haven’t needed you for a very long time. I am not anyone’s responsibility… We don’t need a family superhero. You have created a world for yourself where you have this load-bearing filial and sisterly duty, but it’s all over now, if it ever truly existed. The film is finished. You can just be Grace. Be whichever Grace you want. ”

I don’t know if this novel, or any novel, can cure what ails 2020. Any reprieve offered by art is limited; Leonard and Hungry Paul itself says that “We are never outside of life’s choices; everything leads somewhere.” I certainly don’t believe that gentleness alone can constitute a social panacea. But if Leonard and Hungry Paul’s central message is distilled, it is this: there must be time for kindness, and there must also be time for action, and the one can nourish the other. Millay’s sonnet concludes that, “if I would help the weak, I must be fed / in wit and purpose, pour away despair/ and rinse the cup, eat happiness like bread.” This beautiful, heartfelt book is fed on wit and purpose. In the words of Garth Greenwell, it challenges us to take happiness seriously. The result is that its readers may be nourished by it and in turn nourish others. Hession practices the gentleness he preaches, and gives readers a restorative glimpse of what a world based on embracing our best human quirks could look like. This is a novel to hearten us for whatever lies ahead.