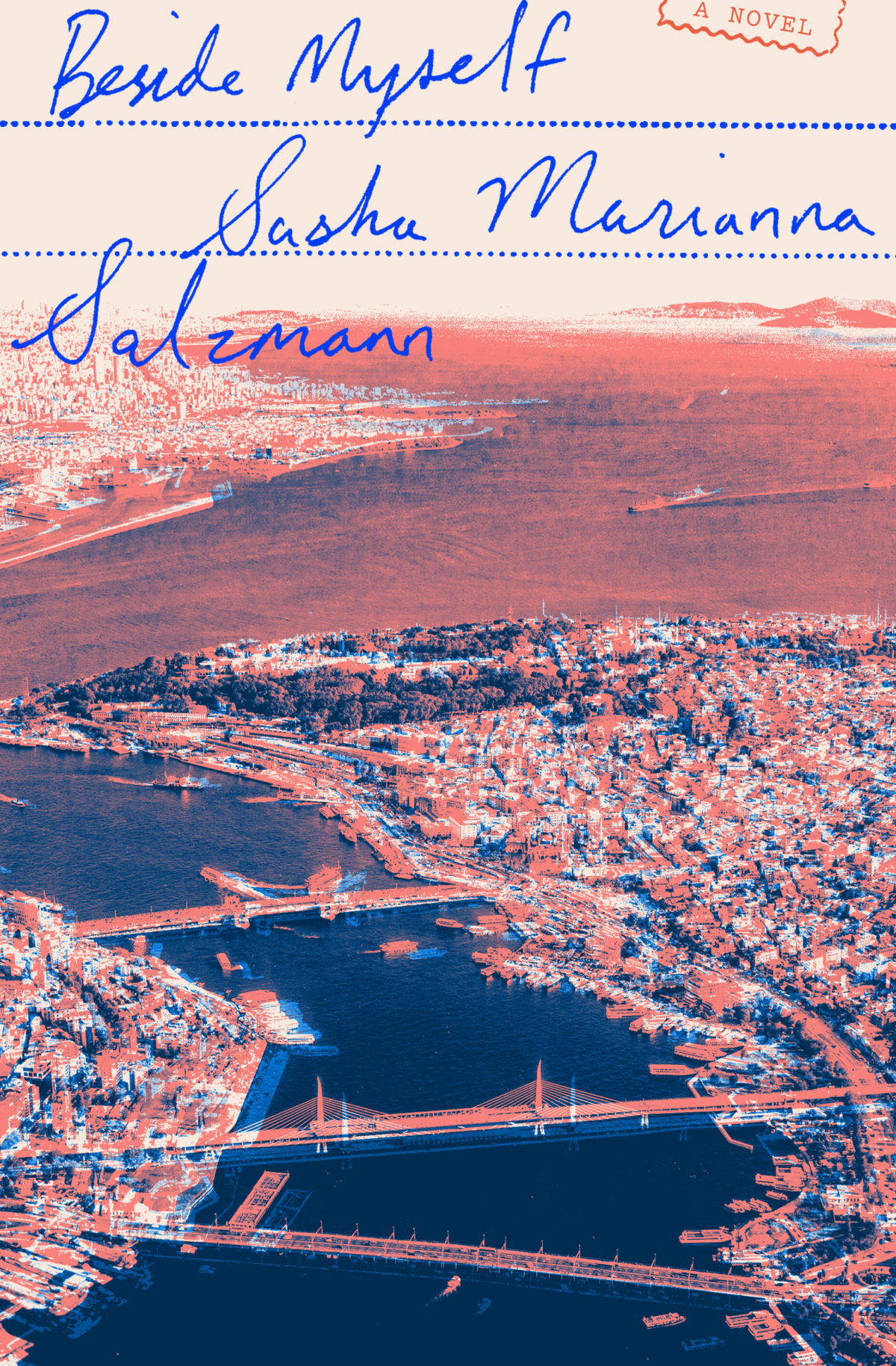

Format: 336 pp., paperback; Size: 5.2 x 8”; Price: $15.99; Publisher: Other Press; Average number of names per character: three; Number of characters who go by Valentina: two; Total number of misogynistic Russian proverbs this book taught me: three; Translator: Imogen Taylor; Representative Passage: “She was speaking several languages at once, putting them together in different combinations to fit the color and flavor of her memories, making sentences that told a story different from the sum of their words. When she spoke, it sounded like an amorphous medley of all the things she was—things that could never have been reduced to one version of a story, or told in only one language.”

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in