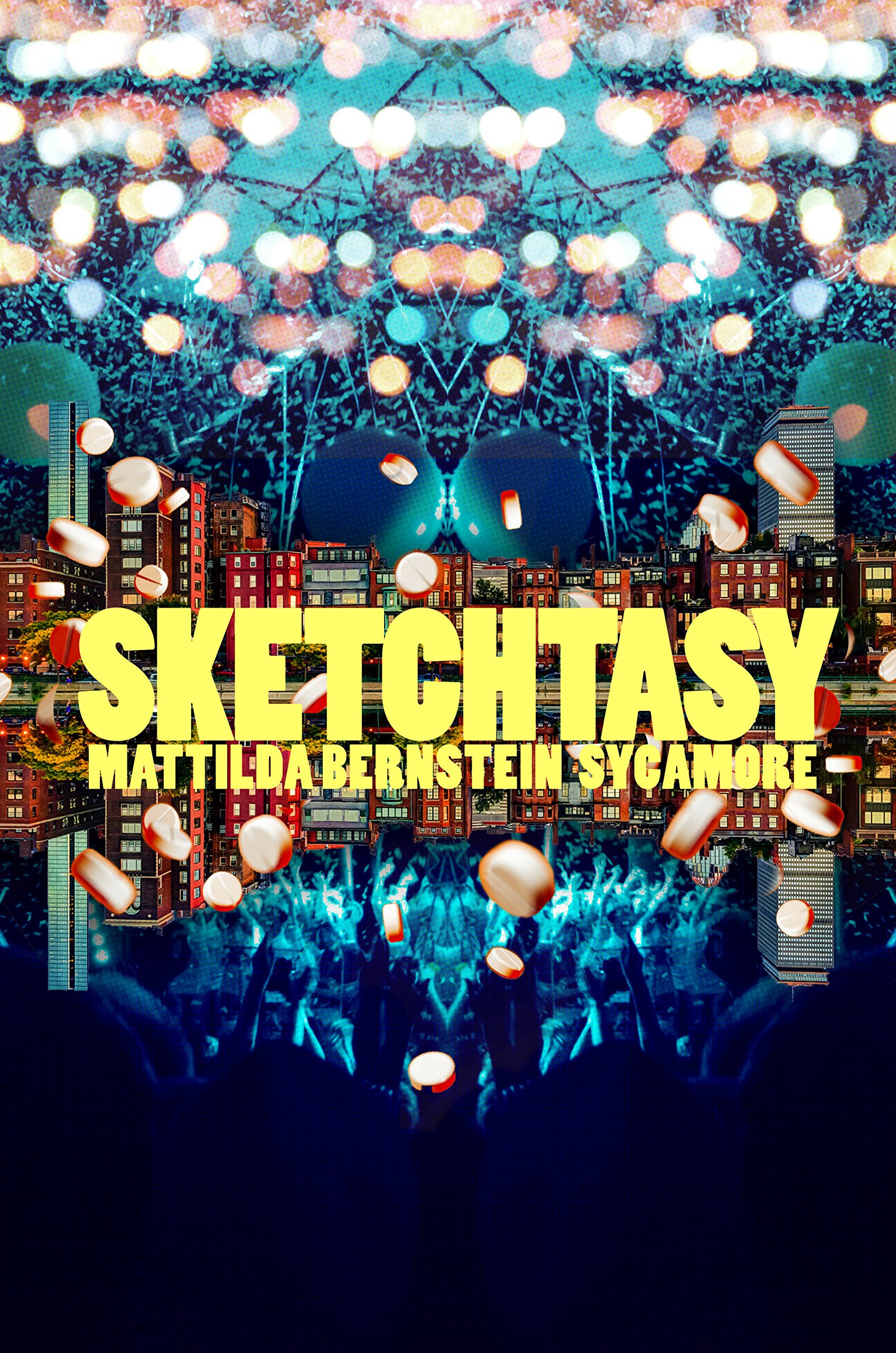

Format: 256 pp., paperback; Size: 6″ x 8″; Price: $17.95; Publisher: Arsenal Pulp Press; Number of times narrator Alexa does ecstasy: at least seven; Number of David Wojnarowicz books mentioned: two; Number of disparaging references to Priscilla, Queen of the Desert: five; Number of AIDS deaths: one; Representative Passage: “I’m wondering why it can’t always be like this—sex, sex work, my life, the music, Boston, the bed, my skin, the air, sweat on his legs, leg hairs, a map, this map, my breathing, hope, close your eyes, eyelashes, pulse, the light, a game, my heartbeat, intimacy—and how can someone’s dick in my mouth feel like a hug…”

Central Question: What kind of world are you left with when the drugs wear off?

In the early pages of Sketchtasy, narrator Alexa is “still strung out from coke, K, pot and ecstasy a few days ago,” moments away from jumping back in, when she goes into the kitchen to make herself a meal. In the other room are random straight Coast Guard boys, Alexa’s vapid roommates flirting with them. Alexa needs to eat, it’s late, the night is young, someone put the Priscilla soundtrack on again—and she’s boiling water for pasta, squeezing tofu over spinach, practicing what some might self-care.

But self-care for Alexa — a 21-year-old genderqueer faggot queen in early ’90s Boston—is far more complicated than the Goop-ified consumer indulgence that the term connotes these days. For Alexa, the spinach may be self-care, but so are the drugs she’s about to do. “Drugs are the best thing for me in Boston,” she tells her therapist. And for Alexa, care for the self is a fight for the self’s very right to exist—an assertion of selfhood in a world that would rather she disappear.

Queer survival is at the heart of Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s published output, which includes two previous novels, a book of essays, and numerous edited anthologies. A long-time activist who came up through ACT-UP and other groups focused on queer-driven, anti-capitalist, anti-racist direct action, Sycamore locates the threat to survival not only in the anti-queer institutions that trickle down into everyday homophobia, but also in the mainstream gays scrambling to assimilate into the very structures designed to oppress them. In Sketchtasy, Alexa is never not aware of this poisonous paradigm: “The funny part is when I walk out on the street in everybody’s favorite neighborhood—yes, the South End—and I’m trying to figure out who’s worse, the gay people who look at me like I’m trash, the straight couples who look at me like I’m going to steal their unborn child or the straight guys who look at me like they want me dead.”

It’s not just Boston, of course, but also—it’s Boston. Alexa has come east from San Francisco in order to go back to school, or because the crystal meth use was getting too evil, and she pines for the radical activist community she left behind. In Boston, instead, she finds friends to do drugs with, to dress up in their best fabulously anti-couture creations and go to the club with, who are at least willing to get rid of their pointless red AIDS ribbons when she tells them what’s up. The drugs, and the music (house music is the soundtrack, delivered with love) can drown out her demand for political purity. Or they give her a means to be less lonely.

Still, Alexa is almost always lonely. She’s just confronted her father about sexually abusing her as a child, and his unwillingness to acknowledge the abuse makes her loneliness an echo chamber, its caverns lightless and resounding. Alexa, in her loneliness, desires the kind of fused intimacy she experienced in San Francisco with her best friend Joanna, who dreamed about feeling Alexa’s “heartbeat in her chest.” Alexa searches for intimacy in sex, too, and sometimes she finds it—with a stranger in gay cruising spot the Fens, with a boyfriend—but sex for Alexa is, most often, work. After she leaves school and her parents cut her off financially, she returns to sex work, eventually moving in with Nate, a wealthy older trick. The presumed intimacy that he brings to their domestic set-up is, for Alexa, a kind of desecration, and the passion she’s expected to bring to their sex is fueled by disgust: “I’ve realized how to channel hate into a hard-on.”

Alexa craves authentic connection, and her belief in its possibility is never fully extinguished, even in the face of unceasing betrayal and loss. And Sketchtasy is just suffused with loss—of friends to AIDS and to drugs, or, just as searing, to the straight world. Alexa’s friend Joanna, who has moved to Boston to kick heroin, decides that Alexa is impeding her path to recovery, and abandons her. When she runs into Joanna, sober, identical to everyone else in the crowd in her Red Sox cap and hoop earrings, Alexa is devastated; instead of losing her best friend to drugs, she’s lost her to something she can’t understand.

Sycamore writes from the wound, and Alexa lives from it. To move on—to trade ripped tights and combat boots for a baseball cap—is a betrayal, even if it’s saving a life. In one of the novel’s most affecting scenes, Alexa loses it when a gay man newly diagnosed with HIV is reassured by his peers that “the new drugs are working”; people are still dying, or chained to a drug regimen that makes them live as if dying, and the new drugs are always going to be too little too late. Alexa doesn’t want bland optimism, or gratitude for table scraps, but righteous anger. This is the anger that drove ACT UP! and the writing of David Wojnarowicz (whose great influence Sycamore cites both in Sketchtasy and elsewhere). Wojnarowicz insisted that his humanity deserved to be recognized because, not in spite of, the specificity of his life on the margins.

Like Wojnarowicz, Sycamore understands that pain, though personal, is also always structural, political, and thus imbued with the promise of collective transformation. Thus the kind of self-care that Alexa performs bears a kinship to Audre Lorde’s oft-misapplied wisdom that self-care is “self-preservation…an act of political warfare.” As feminist scholar Sara Ahmed writes, what’s gotten lost in contemporary, neoliberal understandings of self-care is that “[Lorde’s] kind of self-care is not about one’s own happiness. It is about finding ways to exist in a world that is diminishing.”

Sketchtasy is not, as it might be if it were a different kind of novel, a story of recovery. In a world predicated on the brokenness of its queer subjects, what is there to “re”cover into? Sketchtasy both shows us that Alexa’s drug use is not sustainable, but refuses to shame her for needing to spend time in a world of her own creation. It may be that doing drugs is the closest Alexa can get (for now, in Boston) to another kind of necessary fantasy: a world transformed by radical political change.