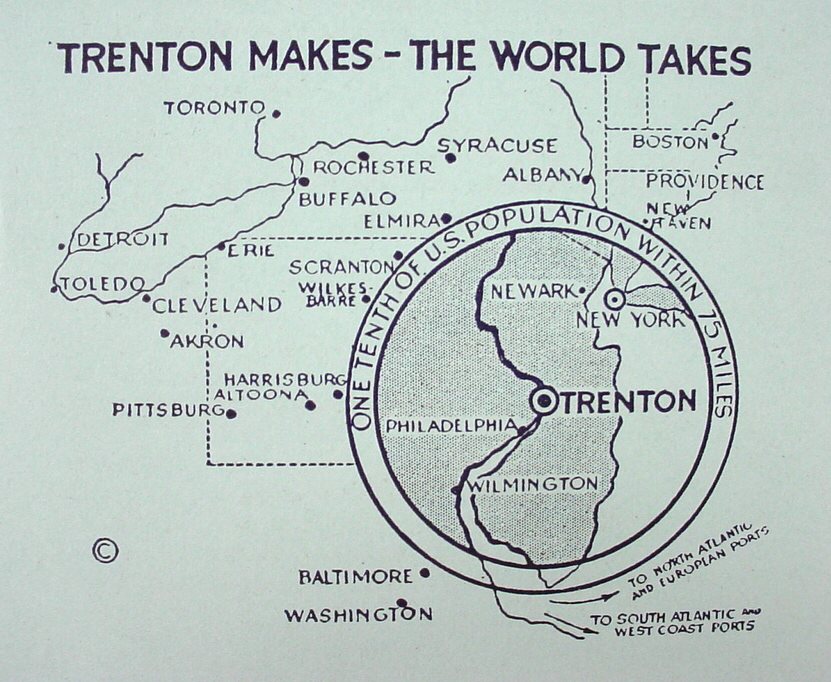

Format: 224 pp., hardcover; Size: 5.7″ x 8.6″; Cigarettes smoked or considered: 16; Population of Trenton, NJ, 1950: 128,000; Population of Trenton, NJ, 1970: 104,000; Percentage Change: -18.75%; Origin of “Trenton Makes, The World Takes”: Chamber of Commerce slogan contest 108 years ago; Representative Sentence: “It was there, in the dance she performed in the morning in their home, that Kunstler perceived the beautiful complexity of it, as if someone had snatched away a panel to reveal the intricate pattern of cogs beneath: the advances and retreats, the range of motions, the fluidity, the relationship to the music.”

Central Question: At what point does the performance of masculinity become destructive?

In Trenton, New Jersey, 1946, the war is over but has hobbled America’s men, leaving many of them hollow drunks, one-upping each other with vulgar jokes and paying dimes and nickels to dance with women in bars after factory shifts. One night, Abe Kunstler, veteran, drunk—a man who “without flinching fought and lied his way into a bare living along the Jersey coast”—comes home and again assaults his wife. His wife has grown strong in one of those same factories while the men were away, and a violent encounter ends with Abe bleeding on the kitchen floor, and later in the building’s basement furnace. She will become Abe Kunstler.

Tadzio Koelb’s manic, panicked novel of identity, Trenton Makes, is the claustrophobic journey of the new Abe. For Aeschylus, murder was the signpost past to which one couldn’t return, and a lie the murderer tells himself is that he can resolve the chaos he’s unleashed. This is certainly the case Koelb is making for Abe and the nation after their demolishing wartimes. To have lived violently is to have no release from a cycle of violence, and to seek outcomes that will again give this result. The result of the war is Abe’s assault, and the result of Abe’s assault is his victim taking his identity and beginning his life anew. The new Abe, setting out with no friends and no confidants and everything on rails, is surely headed toward confrontation and some unknowable, violent end, and will lie to himself as he descends toward this outcome. Koelb only refers to the new Abe, our protagonist, as he/him—there is no reality outside of the new reality of Abe, who wraps his breasts tight with bandages and repeats a vague lie about being “wounded in the war.” Abe leaves a wet razor on the sink’s edge, should anyone investigate his boardinghouse room, and sneaks down the train every morning to yell himself hoarse as it crushes past.

At a job wrapping wire in a factory, the cracks occasionally show. Men complain of Kunstler’s strange ways and that he never dresses with them, but the contortions Abe makes are almost as impressive as Koelb’s, whose ability to maintain the high-wire act is astonishing. It is something like science fiction in how much we’re asked to believe, and yet, Koelb gives us very little space to call attention to the necessity of everything Abe does—the plot and many of Abe’s decisions are preposterous but rendered real and with urgency. Why not run away? Call the cops? Give up this life? Koelb walls off the possibilities—America has failed Abe his run of options. So he finds himself a woman, one who prefers spooning to sex, and his relationship with her becomes a parallel version of his journey. Abe is simultaneously careful and belligerent, but to spectators the woman Inez becomes a light to “shine blindingly in the face of anyone who might think to look at him twice.” (Koelb writes phenomenal sentences.) As long as Abe performs masculinity, Abe remains a man. Masculinity is the lie Abe tells. Now partnered, if Abe ever seems like a woman, he no longer has to pitch his voice or tell a dirty joke—he has a woman, which in Trenton, Koelb seems to say, makes him a man. The high-wire act continues, as Inez is none the wiser. Abe’s private moments disappear entirely. Performance becomes reality.

Trenton Makes is less a novel about passing than one of invention and creation. One where we learn that unfortunately you can become what you want to be by performing it endlessly and with purpose. Koelb’s 1940s and 50s are stuffed with little cruel men, and they’re the men after which Abe models himself, so there is no liberation for Abe by creating himself as a man. These men spit, smoke, drink, and punch each other out. Unlike with The Human Stain’s Coleman Silk, Abe’s new identity does not unbind or free him to some new stratified air. He is born from a furnace and lives in the dirt. Not only will there be no glorious professorship for Abe, there isn’t even a Clark Kent changeover or second costume, no moment where Abe contemplates his advantages and secrets.

Koelb argues that it isn’t just manhood, but the performance of it that obliterates women. Abe is not a former woman inflicting horror on a woman in a world of men—Abe is just a man, and the presence of breasts or any other signifier is no longer as important as the culmination and performance of Abe’s manhood. He will become a man when he brings a child to the world, through Inez. The book’s first act climaxes in a ludicrous series that is as disgusting as astonishing—Abe’s violent beginnings are echoed in druggings, rapes, and assaults, and we are left to contemplate that he will likely be successful in his drive for a family. Koelb notes in an interview that Abe Kunstler is part Doctor Frankenstein and part monster, inventing himself and becoming his own horrible creation. At the first half’s end, like Abe, the reader is bottomed-out, hollowed, and looking anywhere for a good omen, our ears ringing with the worries of past trauma.

The book skips forward to 1971, drawing a line from World War II to Vietnam. Abe has lost fingers in the factory, then his job, and then the respect of his wife and son. His son is not the direct biological creation of Abe, but something he made happen. Accordingly, Abe names him Art. Art has a friend who has been drafted to fight in Vietnam, and the novel follows their attempts to get this boy out of his commitment. In the first half of the book, America’s great failure is behind Abe and haunts him—in the second part, it lies ahead of his son, a smart mirroring by Koelb. The world has changed, and Abe is lost in an America that no longer rewards the man he performed so dutifully for decades. Passing is no longer his concern. Abe’s journey is complete, and wars, assaults, rapes, and the performance of masculinity are all confirmed to be products of each other and simultaneously condemned.

For Abe, to become blameless, boorish, broke, drunk, and disappointing is to fulfill his destiny as a real man. He may be a bad dad, but, dammit, he is a dad. Close to the end of the conflict with his son, Abe convinces himself that “a strength that abides in acquiescence is also a rebellion.” To surrender and be overtaken by a son—to fail, or even to die—for Abe is the same as sovereignty. The lie being told here is the lie of those who send men to war and those who exploit them in factories, and of the capital-letters American Dream. Abe controlled his destiny, for a while. Was there ever a good outcome for Abe? The dead one or the woman who stole his life? Not so long as we focus on what’s missing from the novel’s title. Trenton Makes, America takes.