Artist Books / Artist’s Novels is an ongoing inquiry by Stephanie La Cava that looks at the intersection between visual art and literature. Each entry is a conversation with an artist or writer whose books defy genre expectations and exist outside of the traditional form.

I have admired Tom McCarthy, the writer, for a long time. His books, Men in Space, C, Remainder, Satin Island, and Tintin and the Secret of Literature all straddle the tricky landscape between art and the publishing of written work and its distribution—the topic of this year-long ongoing series. McCarthy’s a masterful novelist with a keen understanding of both the art world and modern literature.

He is also a brilliant speaker, even when simply reading his essays aloud, as he did twice last week in New York, once on the subject of Ed Ruscha at Paula Cooper Gallery and again on “Kathy Acker’s Infidel Heteroglossia” at the Center for Fiction. Both essays appear in the just released Typewriters, Bombs, Jellyfish, McCarthy’s first collection of the kind. We met last week before both talks, at the Half King in Chelsea, in a noisy back garden.

—Stephanie LaCava

I. A World Becoming Text

STEPHANIE LACAVA: I’m wondering about the idea behind using a single letter for the names of your characters. Are there any coded riddles or scrambles? Is there something to look for—say, an anagram?

TOM MCCARTHY: No, no. I called my guy U. in Satin Island because one of the main models of this book was Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, this massive 2,000 page doorstopper of a book. The main character is called Ulrich and he’s similar to my anthropologist. He’s this kind of this over-educated, slightly cynical guy who’s implicated in a massive project that no one really understands. He’s moving through all these salons, exchanging ideas, and there’s some great project afoot, but no one really knows what it is, and the war’s coming and they’re all gonna die. I wanted to write a minimalist version of that.

So I contracted—instead of 2,000 pages there’s 200. Instead of Ulrich it’s U., but it’s also like Baudelaire’s you—like you, the print reader. I love Kafka and all the other abbreviations. It avoids characters of depth and all that stuff you don’t want.

SLC: Was there any relationship to choosing letters with the Ed Ruscha quote that likens text to still life? You’ve also written this wonderful essay about Ruscha, which addressed similar ideas.

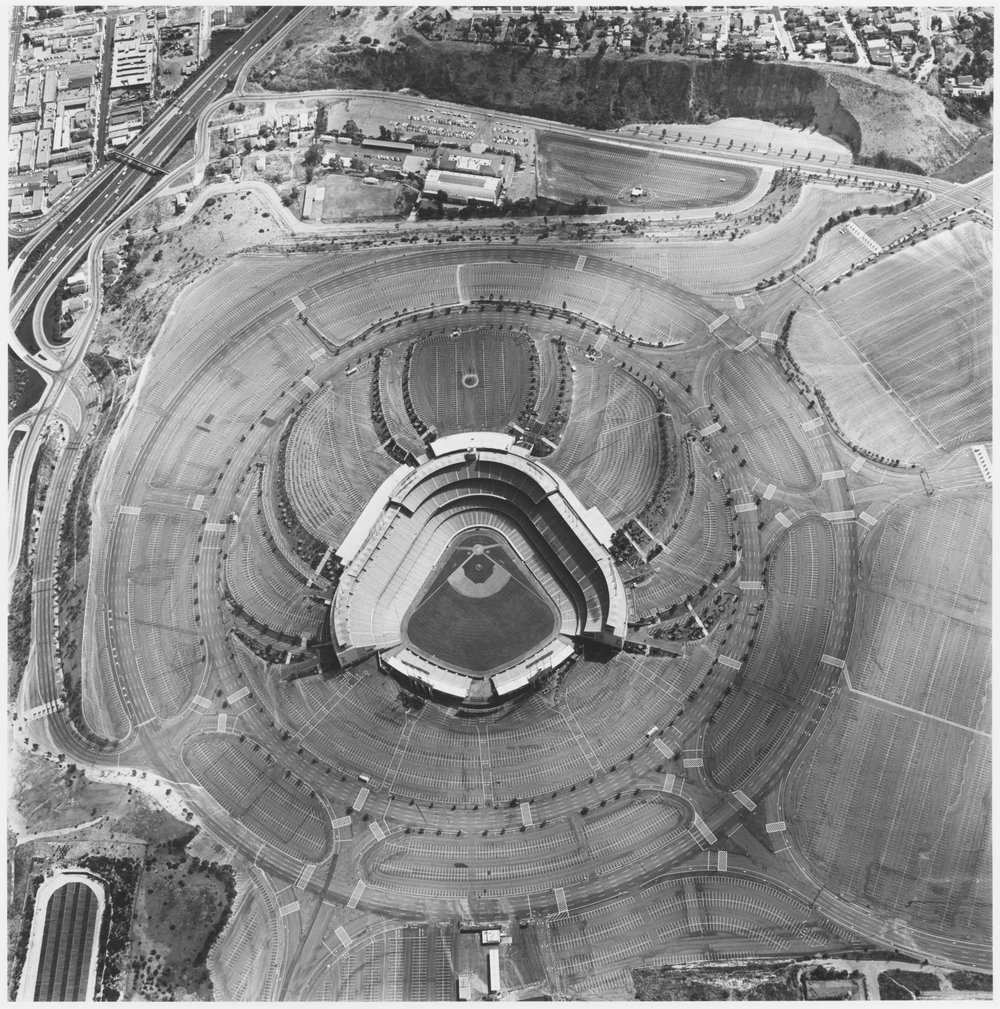

TM: A bit, like when he’s flying over the landscape and they have...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in