Film

Smooth Talk, by Joyce Chopra, 1985

Adapted from

“Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” by Joyce Carol Oates, 1966

Based on

“The Pied Piper of Tucson,” by Don Moser, LIFE Magazine, 1966

I’m willing to bet that most women remember the first time a grown man tried to pick them up. How old were you, twelve, thirteen? Did he ask? How old was he, twenty-five, forty? The first time it dawned on me what was going on, I was standing outside of a coffee shop after school, wearing a staticky dress with my training bra. My mother must have dropped me off while she bought groceries nearby. The only customer on the patio, a man in stiff jeans with stiff hair, asked sotto voce if he could do something for me. I averted my eyes, murmured “no, thanks,” and as I backed away, I abruptly became conscious of how my body moved. In fact, I was never not conscious again. I’d be more prepared for all of the incidents that followed, but the memory of that first time makes my skin crawl. This occasion of unease is the province of Smooth Talk.

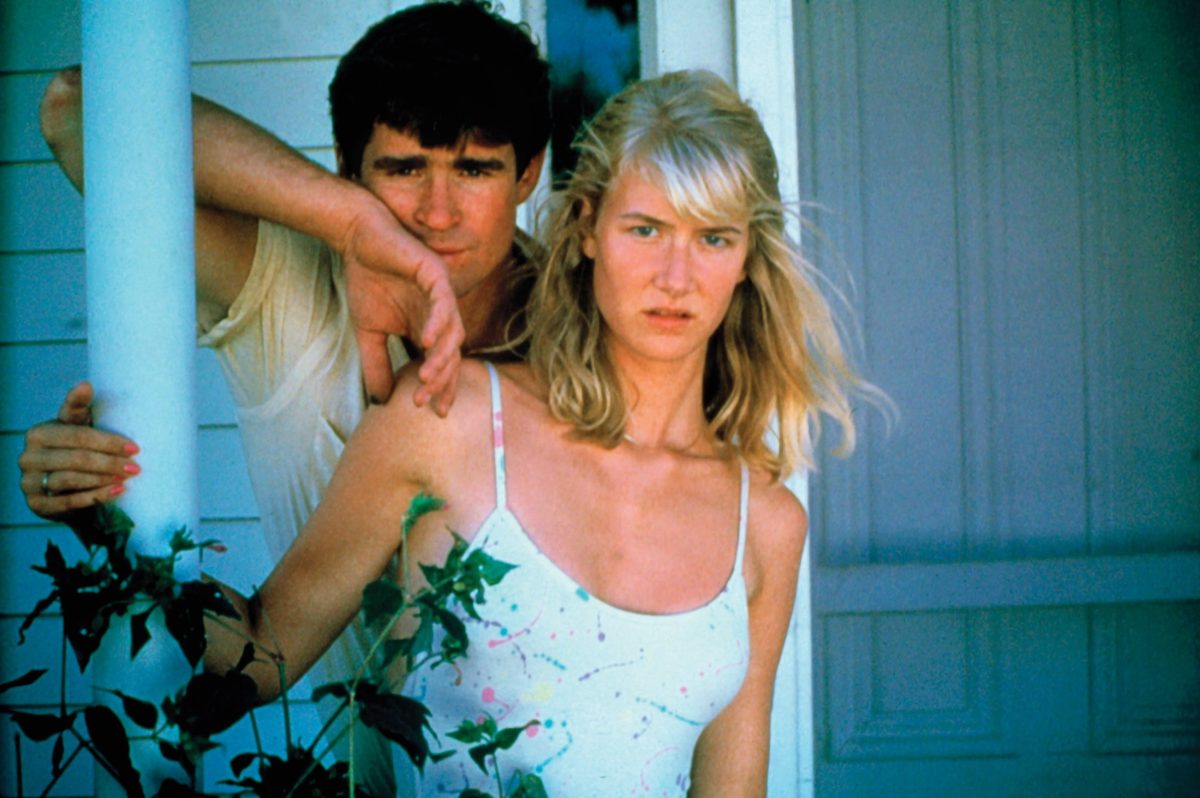

The pre-Manson Family case of Charles Schmid, his unsavory hangers-on, and the three teenage girls he killed led to a volume of reportage, an accomplice memoir, at least two novels, and three exploitation-type films in three decades. Covering Schmid’s trial for LIFE Magazine in 1966, future Smithsonian editor Don Moser created a classic of true crime with his account, “The Pied Piper of Tucson,” which still appears in anthologies. All of the above take as their subject the grotesque perpetrator, who later briefly escaped from prison before other inmates knifed him to death. In 1966, at the beginning of her career, Joyce Carol Oates turned Moser’s tale into something at once less sensational and more harrowing with the also-classic short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been.” In 1985, Joyce Chopra—director of landmark feminist documentary Joyce at 34 (1972)—based her film Smooth Talk on Oates’ story, with her husband Tom Cole as screenwriter, and fifteen-year old Laura Dern in her first starring role. A new Criterion restoration guides the film to the classic status it deserves, and makes it available for the first time in years.

In “The Pied Piper,” the twenty-three-year old Schmid drove a gold convertible with decals, skulked around teenage hangouts, and fashioned himself after Elvis Presley with makeup and dyed black hair, and boots stuffed with rags to add height. Stilted speech and an ingratiating manner topped off his performance. Moser describes one of Schmid’s adolescent victims giggling with a friend and irking her mom, and on the day of her death, listening to rock music while washing her hair and lounging in a swimsuit alone at home—until Schmid showed up with a sidekick, one of his fellow delinquents. He met another of his victims by spotting her at a public pool, following her home, and getting her to come out and talk.

Schmid’s characteristics carry over to Oates’ villain, Arnold Friend, but Oates writes him as ambiguously older. Oates’ Connie is a composite of the girls, but not troubled in the way Moser portrays her real-life counterparts—rather, vulnerable because she lacks worldly experience. Oates focuses on her and not him, introducing her in a couple of pages, sketching her family dynamics and budding sexuality during one idle summer. The rest of the story is the exchange between Connie and Arnold Friend; all we know about him is what Connie learns in the scene. He recites the whereabouts of her family and the names of all her friends, and suggests that he knows her better than they do. He tells her to “be sweet,” a familiar exhortation to girls. Tension mounts throughout the encounter until he eventually deals a few threats to get her into the car. During the conversation, Oates describes Connie’s dawning feeling that her body isn’t quite hers, and her life may no longer be hers; her world has become unfamiliar.

Chopra first read “Where Are You Going” in an anthology in the late ‘70s, and it continued to haunt her. Where Moser’s tone in “The Pied Piper” is caustic and condescending toward Tucson’s youth, Oates holds her teen protagonist at a distance: she’s explained in interviews that she intended a Hawthorne-like remove, to give the story an allegorical quality. Perhaps because Chopra had a middle school-aged daughter at the time of Smooth Talk, her depiction empathizes viscerally with Connie. In the film, Connie fights with her mom (the perfectly fed-up Mary Kay Place; The Band’s Levon Helm plays her father); she works on her tan, and plays her radio while she bathes. She makes a scene with her friends at the mall, and shakes off the ones who can’t keep up. She looks for boys at a cruisy burger joint, and soon someone else is looking for her, and a setting without witnesses. Treat Williams’ Arnold Friend isn’t outlandish like Oates’ version, or Schmid: no implausible marks of vanity, just the slick car and insidious way, making him all the more treacherous. It’s easy to see why Connie voluntarily emerges from the house to flirt with him.

Mood-wise, Chopra takes us from Bonjour Tristesse to Funny Games in the span of a single scene, a move she somehow executes both suddenly and subtly. Arnold Friend comes just a little too close to Connie, and she begins to comprehend that her safety is fragile. When he propositions her outright, her rising alarm turns to terror. The film is spellbinding as it enacts the paralysis the story describes, the palpable sense of entrapment. Connie may even think that she brought the event upon herself, the way her mother implies that she’ll do. Even more unsettling than the profound shift in tone, the only conversation between the two leads starts an hour into the movie—so we find ourselves finishing a very different film from the one we began, and realize this outcome was stalking us all along. Connie is the Final Girl we hadn’t known to look for.

Translating true story to fiction to film tends to encourage embellishment: more sex and gore, subplots and twists. In this case, we have the opposite. Oates pares away the lurid scandal of the LIFE piece, down to a regular teenage girl and a highly irregular day in her life. Chopra uses this narrow scope, and focuses on going deep into Connie’s world, small and commonplace, but richly textured and ripe with anticipation. By the time Arnold Friend rolls up, we have a sense of what’s at stake, and Connie isn’t just bait for this predator. The exploitation films tended to implicate the murdered girls: in one, a victim dares the killer; in another, a victim is having an affair with a married, much-older detective. But Connie is just beginning to make out with boys, friends of her friends from school. She admires herself in the mirror, trying on her newfound power. Together with cinematographer Jim Glennon (who’d just shot the masterful, heartrending El Norte), Chopra does a marvelous job of imparting Connie’s voluptuous thrill as her date caresses her shoulders in his car. It transported me back to that time—a couple years into racier bras, but not really close to adulthood—like no coming-of-age film I’ve seen, capturing its delicious discovery, and the sometimes-faint line between risk and self-possession. Dern has commented in interviews that she feels fortunate to have had Chopra’s set be her first experience shooting love-type scenes, where she felt safe, respected and cared-for, when many young actresses haven’t had such luck.

It was essential to Chopra to cast a girl “in the breach” between childhood and maturity. Two weeks before the film was set to shoot, she hadn’t found what she sought in a lead, when her still photographer Nancy Ellison interjected during a phone call, “I see her! She’s walking by! It’s Bruce Dern’s daughter!”

Indeed, Dern herself seemed uncannily like the character. Chopra’s friend and neighbor James Taylor had asked to soundtrack the film (its one true flaw, in my opinion), and when she called Dern, the girl’s answering machine message played the song Chopra had picked for the theme. Chopra had chosen a James Dean poster for Connie’s bedroom wall, and when Dern picked her up in her car, the image was on the actress’ dashboard. Oates has commented on Dern’s performance that she, as Connie’s creator, can’t see the character any other way.

Dern made Smooth Talk after Peter Bogdanovich’s Mask, then acted in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. She’d have her next starring role in Lynch’s Wild at Heart, where she’d play a different kind of ingenue, but still a naïve one, her scene with Willem Dafoe recalling Smooth Talk’s pivotal instance with Williams. In 2018 with The Tale, she’d play the grown version of a thirteen-year old girl preyed upon by an adult man, looking back at how he groomed her, sweet-talking while he coerced her (writer-director Jennifer Fox based it on her own experience). Dern has said that in her career, she’s often reached back to the tormented moment in Smooth Talk’s shadowed hallway, when Connie’s too scared to pick up the phone. That conversation with Williams is the longest scene she’s ever had, and she remembers it as a precious gift.

I was taken aback to learn that kids read Oates’ story in school now, perhaps as an unsubtle warning about the perils of talking to strangers. Girls and women in trouble, often facing sexual violence, are a recurrent theme in Oates’ work, and this story is one of her best-known. In sixty-five years, she’s published over 150 books (!), most fiction, many successful both commercially and critically. Yet only a handful of her works have made the leap to feature-length film, and half of those for TV. There’s Foxfire (with Angelina Jolie), Lies of the Twins (with Isabella Rossellini), Getting to Know You (with Heather Matarazzo), Vengeance: A Love Story (with Nicholas Cage), and miniseries We Were the Mulvaneys (with Blythe Danner) and Blonde—which Chopra made in 2001 (with screenwriter Joyce Eliason; a remake with Ana de Armas is currently in post). Oates has declined to watch some of these, but Smooth Talk blew her away. The first feature adaptation of her work, Smooth Talk won the Grand Jury award at Sundance when it premiered in 1986. The festival was only four years old then; the year before, Blood Simple had won. Stephen Spielberg, already a father, told Chopra that Smooth Talk petrified him. Other men in the industry told teenage Dern that it turned them on.

The Oates story doesn’t give a location, but the film shot in the north Bay, in Marin and Sonoma counties. When I was in middle school, my family would drive from the south Bay up through San Francisco and over the Golden Gate, on our way to Santa Rosa to see relatives. We’d pass through Petaluma, one of Smooth Talk’s locations, and I’d always think of Polly Klaas, the girl my age taken from home during a slumber party. The search and the subsequent trial kept the case in the news for years, and led to California’s infamous “three strikes” law (the unrepentant killer had prior convictions). On the approach I’d look out the car window at the paraboloid Birkenstock building off the road, but even now, when I hear “Petaluma,” the girl is the first thing I think of. We’d continue up through Sebastopol’s apple orchards, where Connie’s family lives in the film, and along the Russian River, to vacation on the Mendocino coast. My father had vacationed there when he was my age, and he told me about having once been approached by a man in the swimming pool locker room. He began to follow my adolescent father, asking to take pictures of him. My father, who described his young self as “clueless,” still grokked that something was wrong. When the family returned home to the east Bay that summer, the man showed up at their house, but my father refused to come out of his room. Years later, my father learned that the man was in prison for sex crimes against boys, exposed in photos he’d taken.

While Smooth Talk mostly adheres to the beats of “Where Are You Going,” Chopra altered the ending from Cole’s script. The director had the choice: sacrifice Connie to one of the men who spot kids at the pool, the café or the film fest, who catch them with friends or find them at home, the ones with the cars, cameras and knives—or give her a chance to survive her ordeal? Oates’ story closes with Connie’s departure, so Cole had imagined ending on the screen door swinging shut as Dern leaves. But on set, Chopra changed plans: unlike the girls in Tucson, in the film, Connie comes home. She arrives back just after her family, and embraces her suspicious big sister in a moment Oates has praised as “transcendent.” She’s no longer the same girl; nor is she a casualty. Connie is one of the lucky ones.