In 1930, Harry J. Anslinger was appointed the first commissioner of the newly founded Federal Bureau of Narcotics. It was a major promotion for the 38-year-old former Pennsylvania Railroad investigator, and he didn’t intend to squander it. But Anslinger was stepping into a precarious situation and he knew it.

The Bureau of Narcotics was an outgrowth of the Bureau of Prohibition, the federal agency tasked with enforcing the nation’s ban on alcohol. But the war on booze was in its death throes, and the agents staffing the Bureau of Narcotics, largely drawn from the Bureau of Prohibition, were a baggage-riddled bunch, venal and demoralized.

With the new agency’s meager budget and unclear raison d’être, there was little to suggest a course correction. Anslinger quickly realized he had to give his fledging agency a worthy cause to justify its continued existence and galvanize a listless force. With alcohol all but legalized, Anslinger set his sights on two new scourges: marijuana and heroin.

Late one night in the fall of 1933, a young man named Victor Licata used an axe to murder his parents, two brothers, and a sister in their Florida home. Early police reports suggested he was a heavy marijuana user, and the press seized on the chance to sensationalize a grisly crime. Soon the so-called “axe-murdering marijuana addict” embodied Americans’ worst fears about the risks of cannabis use.

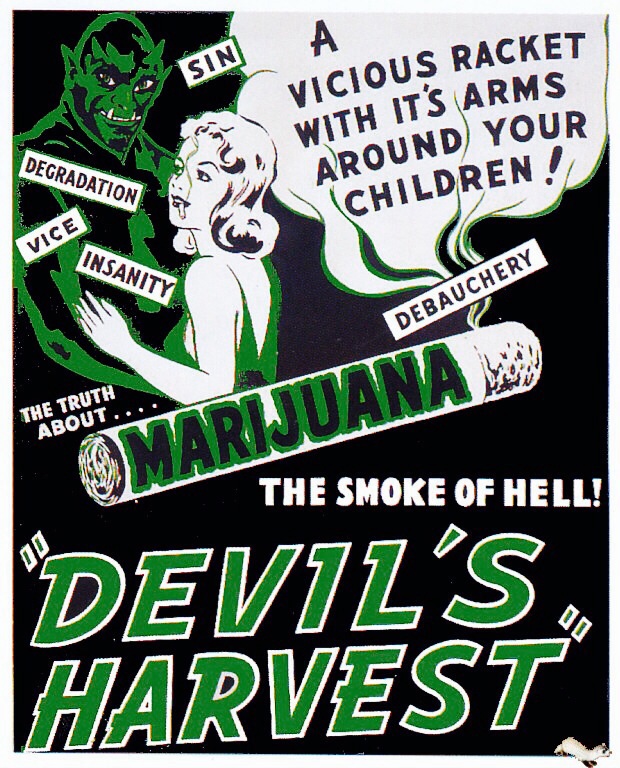

Crafty and opportunistic, Anslinger watched the public frenzy surrounding Licata. He observed how marijuana could serve as a kind of vessel for paranoia, subsuming sentiments that might otherwise float freely in the ether—ideas about disorder, subversion, and youth run amok. Anslinger wondered if he couldn’t leverage that symbolic power to crystallize his new agency’s cause. In the midst of the media maelstrom, he used Licata’s rampage as one of the first entries into what became known as the “Gore Files”: articles drawn from police reports detailing heinous crimes allegedly committed under the influence of marijuana.

For most of the 1930s, Anslinger collected these stories and used them with the flair of a PR mastermind. Utilizing his connections at national newspapers—including a close friendship with publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst—he turned police blotters into lurid tales of young people transformed by marijuana cigarettes into murderers, rapists, and thieves. Other “files” include the alleged case of a lesbian stabbing her lover in a row over marijuana use and two girls from New Jersey who got high and shot a bus driver to death over a $2.40 fare.

Anslinger eventually published 200 of these stories in newspapers and magazines, wielding a powerful command over public opinion at the time. That 198 of the 200 crimes recounted in Anslinger’s Gore Files were eventually discredited as the result of cannabis use didn’t matter. The task he set for himself was to shape how people felt about marijuana, to conjure into existence a constellation of negative associations about the drug. In the process, he hoped, he’d rally a fierce opposition to it.

From the outset of his time as commissioner, Anslinger’s approach was unique. He didn’t just denounce drugs on medical or moral grounds. He portrayed them as subversive elements capable of disrupting the social order. Those who learned about marijuana only through his Gore Files might see it as the common denominator in all kinds of heinous acts—the devil in the details of violent crime sprees, fits of madness, and depraved pedophiles.

In addition to the Gore Files, Anslinger—whose bigoted views were notorious even within his own agency—worked to reshape the public image of drugs around racist stereotypes. In his writing, campaigns, and congressional testimony, Anslinger consistently cast marijuana as the shiny lure predatory black men used to ply innocent white women. In one file, he wrote about “Colored students at the Univ. of Minn. partying with female students (white), smoking [marijuana] and getting their sympathy with stories of racial persecution. Result: pregnancy.” In another, he warned readers how marijuana “causes white women to seek sexual relations with the Negroes, entertainers, and any others.” For Anslinger, drug use threatened the racial hierarchy that undergirded the country. In fact, it seemed to facilitate racial equality, a concept he regarded with deep dread.. Through Anslinger’s propaganda, the public perception of illicit drugs gradually morphed into something entirely new: the embodiment of people’s worst fears about the racial Other in America.

For Anslinger reefer madness was about more than just debauched youth, or even fantasies of criminal pathology. As Martin Torgoff explains in Bop Apocalypse, a history of jazz and drug policy, Anslinger and others feared “the sexual boundary between the races would vanish as if by some perfidious deed of black magic” if there was too much lighting up, “and the great taboo of interracial sex would come tumbling down forever.” Marijuana, they feared, had the potential to undermine segregation and subvert the white male patriarchy.

Among Anslinger’s favorite targets for his racist propaganda were black jazz musicians. Despite ample evidence of famous white addicts, including Oz’s Dorothy herself, Judy Garland, Anslinger held African-Americans entirely responsible for the heroin resurgence in the 1940s. At one point he declared that increased drug use “is practically 100 percent among Negro people.” During his 32-year tenure as commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, he had his agents spy on Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Thelonius Monk. He hoped to arrest them all in a single triumphant display, a one-day “national round-up” of black musicians.

He saved his most dogged pursuit for singer Billie Holiday. After Holiday sang “Strange Fruit” in a midtown Manhattan hotel in 1939, Anslinger’s men sent her a warning to never perform the song again. Because Holiday defied the order, continuing to sing her hypnotic ode to Southern lynching, Anslinger harassed her for the rest of her life. Over the next two decades, his agents busted her on drug possession and sent her to prison, prevented her from getting a cabaret singer’s license, and stormed into her hospital room after she’d collapsed, handcuffing her to what would become her death bed.

Holiday, a black jazz singer crooning about racial oppression, epitomized everything Anslinger felt threatened his version of America. That she’s remembered as a troubled heroin addict almost as vividly as she is a gifted musician 70 years after her death is a testament to the way the Bureau of Narcotics and the media campaigns it deployed overlaid black culture with drug culture.

II.

The sprawling initiative that Anslinger began would later be recognized as the War on Drugs. In the 1970s, President Nixon took up the mantle. The actual term was born out of a speech Nixon gave to congress in 1971 during which he outlined how to “wage an effective war against heroin addiction.”

Nixon’s War on Drugs, like Anslinger’s before him, was largely a proxy fight against specific racial and cultural groups. Nixon aide John Ehrlichman conceded the president’s strategy in a 1994 interview with Harper’s. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or blacks,” he said, “but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

In an effort to tie the groups to marijuana and heroin and destabilize their leadership, Nixon emboldened drug agencies by beefing up their budgets and expanding their powers. He created a whole new law enforcement agency, the DEA, to hunt down suspected drug users. Nixon refined Anslinger’s War on Drugs into a political weapon, something that could sabotage opponents, consolidate constituencies, and control narratives. In addition to persecuting African-Americans and war protesters for political gain, Nixon’s Southern Strategy during the 1972 presidential election used a tough-on-crime, anti-drug platform to appeal to racist southern voters.

Any pretense of an earnest effort to reduce America’s illicit drug use had surrendered to politicking. A decade later, President Ronald Reagan launched his “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign in response to public hysteria over crack cocaine. The upshot of this iteration—fueled, once again, by a wild demonization of black culture—was a tenfold increase in the number of individuals incarcerated on drug offenses from 1980 to 1996.

The effect has been a kind of Ponzi scheme: replacing one patsy with another, generation after generation, to explain America’s outsize appetite for heroin, cocaine, marijuana, and prescription pills.

But if the country’s leaders were inventing boogeyman—criminal psychopaths, jazz lotharios, and feral crackheads—to explain America’s drug problem, then the real culprits were getting off scot-free. After all, our disproportionate drug use in comparison to the rest of the world is a real thing. It’s the dense thicket of fable and fantasy surrounding it that’s illusory.

III.

The origin story of American drug use has a Victorian novel’s mix of treachery and squalor. During the second half of the 19th century, many of the most powerful, addictive substances in existence today were perfected in a lab, draped in elaborate advertising, and sold to the public. It was the era of potions and panaceas, robust tinctures and grandiose remedies that promised vitality, relaxation, great sleep, and placid babies. That people were getting stoned on throat lozenges, cold medicine, eye drops, and soda pop was beside the point—at least for a while.

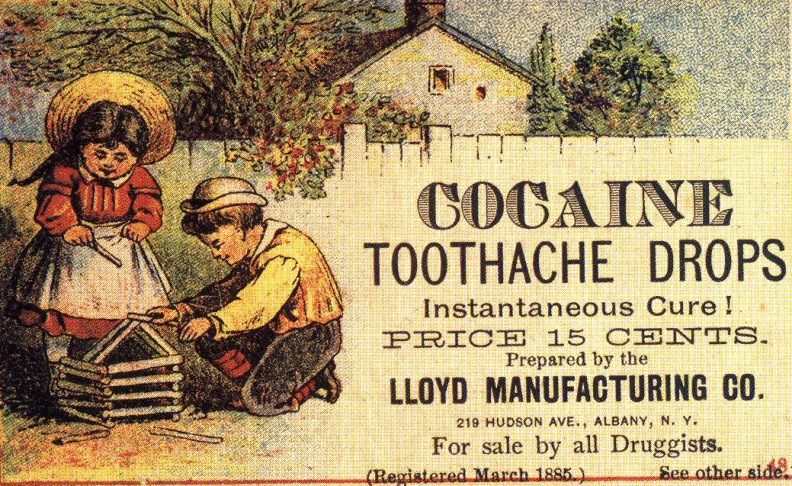

In 1859, German chemist Albert Niemann successfully isolated cocaine from the coca plant. By the 1880s cocaine’s virtues were espoused by everyone from Surgeon General William Alexander Hammond and Sigmund Freud to Ernest Shackleton, who used “Forced March” brand cocaine pills on his expedition to the South Pole. Throughout the decade, surgeons and neurologists experimented with the drug as a local anesthetic and nerve-blocking agent. In one notorious example, ophthalmologist and Freud associate Karl Koller demonstrated the drug’s efficacy by dropping a cocaine solution into his eye and then pricking it with pins. The general congress of ophthalmology hailed it a medical breakthrough.

Cocaine began as a scientific curiosity, piqued the medical community’s interest, and then filtered down to the rest of society. Because it first passed through prestigious circles—however briefly—it had a cachet of legitimacy that reassured an otherwise apprehensive public. In 1886, Georgia pharmacist John Pemberton turned the drug into a household drink, Coca-Cola. Other cocaine tonics, including Vin Mariani and Caswell Hazard & Co.’s Coca Wine, were also highly popular at the time.

Print advertisement for cocaine toothache drops

Print advertisement for cocaine toothache drops

Before the foundation of the Food and Drug Administration in 1906 and the increased oversight that followed, traveling “snake-oil” salesman—the pharmaceutical sales reps of the 1800s—peddled patent medicine door to door. In the 1880s and 90s pharmaceutical companies used these salesmen to bypass doctors completely, and unregulated print advertising made extravagant promises about drugs’ virtues. It was a Wild West where the pharmaceutical industry first cut its teeth promoting drugs in as many ways, and through as many channels, as they could.

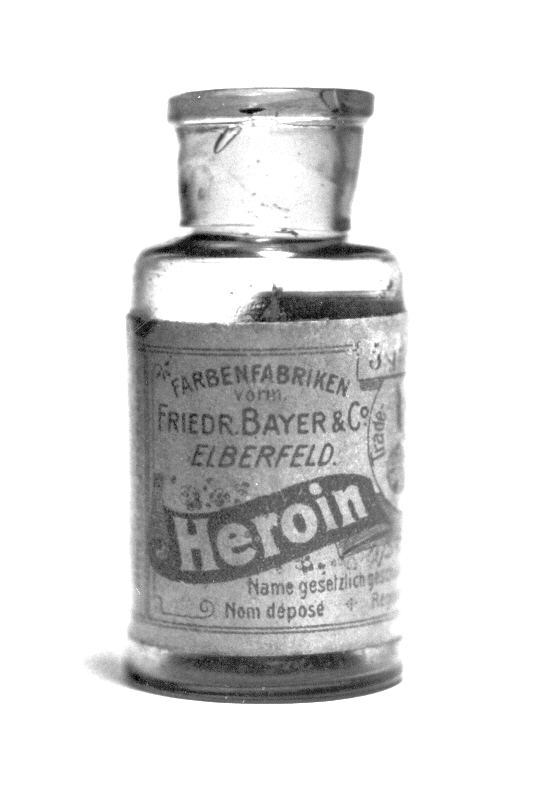

Opium and its derivatives had a similar trajectory to cocaine. Soldiers began using intravenous morphine during and after the Civil War to help assuage what were often grisly injuries. But this limited medical purpose was gradually rent open. Pharmaceutical companies and their advertisers saw an opportunity to sell opium and morphine to a larger swath of the American population, and went about dressing up the drug accordingly. Laudanum, a mixture of opium and alcohol, was sold without a prescription and frequently marketed to women of means as a cure for everything from menstrual cramps to insomnia. In the 1890s Sears & Roebuck sold hypodermic kits—a syringe, two vials of morphine, and a carrying case—for $1.50 in its popular catalogue.

Morphine and opium proved highly addictive, and the opioid craze of the late 19th century eventually spiraled out of control. “Of all the nations in the world,” Opioid Commissioner Hamilton Wright told the New York Times in 1911, “the United States consumes [the] most habit-forming drugs per capita.” Americans, he declared, “have become the greatest drug fiends in the world.”

As the period spawned more and more addicts, the pharmaceutical industry gave itself a curious challenge: develop a drug to combat the suffering wrought by the drugs they’d just developed. In 1895 Bayer brought to market a new pain reliever, synthesized from morphine. Its trademark name: Heroin. The head of Bayer’s research department got the name from the German word for heroic. Bayer claimed its new drug would have the same curative effects of morphine without the drawbacks, declaring it a “non-addictive morphine substitute.” It was marketed as a pain reliever, cough suppressant, soporific, and effective treatment for “over reliance on morphine.”

In the span of just a few decades, cocaine, opium, morphine, and heroin were all introduced into America. They were also all perfectly legal, over-the-counter medicines touted by pharmaceutical companies as tidy cures for whatever ailed you. That they came with a kicky rush of euphoria just made everything go down easier.

If we want to understand why America consumes more drugs than any other country in the world, the decades after the Civil War seem like the right starting point. Some of society’s most lethal and addictive drugs were first synthesized in that period, and then marketed to just about every American demographic. Drug manufacturers told veterans, housewives, and children they could all lead healthier, happier lives with the aid of these new morphine-, heroin- and cocaine-infused products. When the federal government finally imposed regulations on those products with the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, it was against vehement opposition from pharmaceutical companies.

Anslinger’s three-decade stint as head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics gradually overshadowed all that, though. As the chief pioneer of the print stories, media narratives, public service ads, and political capital that can all today be filed under drug propaganda, he banished to history’s footnotes the pharmaceutical origins of most narcotics. Over time, the stereotypes he conceived were taken up by politicians, reporters, and everyday people, creating the images and assumptions we now associate with “drug culture.” But by forgetting how “the greatest drug fiends in the world” came about in the first place, Americans were simply perpetuating a disingenuous, frequently racist charade that was usefully convenient until it wasn’t.

IV.

Huntington is a city of 50,000 on the southwestern edge of West Virginia. Founded in 1871 at the confluence of the Ohio and Guyandotte Rivers, it was once home to humming steel manufacturers and sprawling coalfields. Decades of decline in those industries, however, have conspired to create what is today a particularly decayed patch of the Rust Belt. West Virginia is the second-poorest state in the nation, and Huntington—which has seen around half of its manufacturing jobs disappear since 1950—is among the most impoverished areas in the state.

But West Virginia’s true superlative is not its poverty. As of 2017, it had the highest rate of fatal drug overdoses in the country. Perhaps because of Huntington’s high unemployment and its geographical location—a short drive from both the Ohio and Kentucky borders—the city’s overdose rate is three times the state average. In the past few years, as locals have moved from prescription opioids to heroin, overdoses are increasingly common in the working-class city.

A Monday in August of 2016 is a macabre case in point. Sometime shortly after 3 pm, emergency responders got a call that people were “just showing up and dying” at a Huntington home. When officers arrived at the house, they found three people lying unconscious in the yard. Inside, four more were comatose, including a man who’d collapsed on the dining room floor and whose abscessed flesh had turned a dark blue.

Thrust into triage, police focused on those who were still breathing. To shock them back to life, they knuckled their sternums and injected them with naloxone. It was a tense, grim scene, with lives hanging by fickle threads. This house of the half-dead, though, was just the beginning of an even uglier night.

911 dispatchers got another call about an overdose just a few minutes later. More poured in as the afternoon slipped into early evening. People were shooting up and then losing consciousness in gas station bathrooms, Family Dollar stores, and in the middle of traffic. By 9pm that night, first responders in Cabell County had fielded calls for 26 overdoses from Huntington. There was likely a bad batch of heroin going through the city, one laced with fentanyl. It must have been like the opening scene to a post-apocalyptic thriller: spasms of horror visited upon parking lots, grocery store aisles, and traffic jams at chilling random.

Thanks in large part to naloxone, only two of the overdoses that day in Huntington were fatal. But the speed and suddenness with which catastrophe struck underscores how malignant America’s opioid epidemic has become. In its current chapter, heroin has emerged as the cruder new antagonist, a nasty killer that works for cheap. When pill mills shut down, doctors grew more circumspect, and street prices skyrocketed, addiction itself remained change-proof, a black obelisk looming over an otherwise fluid landscape.

Though the prescribing of opioids has finally been reigned in over the past half-decade, a mortal vulnerability has already been etched into millions. Twenty years after OxyContin was first approved by the FDA, that vulnerability has brought a murderer’s row of deadly hard drugs into the basements, bathrooms, and bedrooms of this country. It’s a mirror image of the 19th century pharmaceutical drug boom, right down to the black markets created in the wake of belated regulations.

We’re now experiencing the worst drug crisis in American history. There were 64,000 fatal overdoses in 2016, the most ever (preliminary data indicates 2017 could be even higher). The death toll that year was higher than the total number of Americans killed in the Vietnam War. It’s a sad state of affairs, not only because of the lives lost but because those deaths are just the tip of a much larger iceberg of addiction. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) estimates that around two million Americans abuse or are dependent on prescription opioids, and a study by Blue Cross Blue Shield found that the number of people with an opioid addiction jumped 500 percent from 2010 to 2016.

Many trace the genesis of our current epidemic back to the 1990s, when pharmaceutical companies began lobbying to use pain medication for non-cancer pain. But while that sowed the seeds for widespread opioid use, it wasn’t the start of this country’s unusual relationship to drugs. There’s a broader context to consider here: America consumes more drugs than any other country in the world. Among 195 nations, the U.S. comes in first in marijuana, cocaine, and prescription opioid use. It’s also far ahead in fatal overdoses. We stand out with particular distinction when it comes to pain pills: while comprising only four percent of the world’s population, we consume 80 percent of the global opioid supply.

To understand how Americans came to be the world’s biggest substance abusers, we need to reassess the history of the nation’s drug use. Since Anslinger’s rise, America has defaulted to hiding its drug habits behind stereotypes and dog-whistling political campaigns. The real question is: when you pierce the veil of Anslinger’s racist tableau, what do you find underneath?

A bottle of Bayer heroin

A bottle of Bayer heroin

V.

According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, run by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, white Americans use cocaine, methamphetamine, and opioids at a higher rate than do blacks. They also have a higher lifetime rate of overall illicit drug use. It’s white Americans, for the most part, that drive the nation’s rank as the largest consumer of drugs in the world.

Vast quantities of government resources, though, have gone to ferreting out the drug problem among African-Americans. Today black men are six times more likely to be incarcerated as white men, an inequality largely driven by mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. This disproportionate policing makes little sense for a minority that makes up only 14 percent of the U.S. population and does not use drugs at a higher rate than other groups. Is it really a surprise that such a groundlessly narrow operation would be inept in the long run? By exploiting scapegoat logic and following through with discriminatory policies, successive presidential administrations sacrificed decades of potentially more competent drug policy.

In the mid-1990s, Stamford, Connecticut-based pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin. In the years that followed, Purdue proceeded to launch a sprawling marketing campaign through videos, brochures, conferences, and even starter coupons for free 30-day supplies. The result was a tenfold increase in OxyContin prescriptions for non-cancer pain from 1997 to 2002. In a detail that bears a ghastly symmetry to Bayer’s Heroin a century earlier, OxyContin was marketed as an “abuse-resistant” alternative to other opioid medications.

Many now cite OxyContin as the drug that kicked off an opioid epidemic that’s killed over 200,000 people since 1999. As prescription opioids became increasingly hard to get, users turned to heroin—once upon a time itself an aggressively marketed prescription drug. The entire illicit drug market runs on pharmaceutical refuse, and the lines that separate patients from addicts and medicine from dope are just features of the messy palimpsest the industry leaves in its wake.

America is one of only two nations in the world, along with New Zealand, that allows pharmaceutical companies to advertise directly to consumers through television, print, and radio ads. This is known as Direct-to-Consumer-Advertising. These U.S. advertisements cost the industry over $6 billion a year, but also drive by far the largest pharmaceutical market in the world. At $340 billion, we spend three times more than any other country in the world on prescription drugs. If most illicit drugs start out as prescription medications, should it come as any surprise that the country with the largest prescription medication market would have a commensurately large black market for drugs?

For decades Henry Anslinger and the racist template he set masked a relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and the messier underworld of drug trafficking and recreational use. What’s clear is that it’s symbiotic and slyly codependent, and the latter would hardly exist at all if not for the former. Evidence spanning centuries also demonstrates that misuse usually starts with insufficiently understood pharmaceutical drugs, only later trickling down to nourish a darker world of clandestine abuse and addiction.

Instead of a growing awareness of this connection, Anslinger’s tactics had America believe that drug epidemics billowed out of monstrous racial caricatures—black predators stalking dorm rooms and jazz clubs with their joints and needles. But the ruse came at steep cost. The War on Drugs initiated by Anslinger and taken up by presidential administrations throughout the 20th century wasn’t just a failure because it didn’t stop America’s fatal attraction to narcotics. The War on Drugs has been a failure because it sabotaged that aim, confounding any hope of understanding the roots of our pernicious appetites.

Regardless of precisely how culpable companies like Purdue Pharma are for the 91 fatal overdoses that occur in America every day, there is no disputing that this is the second time in a century the pharmaceutical industry propelled a merciless drug epidemic. And the double standard with which consequences are meted out is crystal clear. Since the beginning of drug enforcement to this day, federal agencies have targeted the small-time, low-level dealers and their customers without ever mustering the courage to take on the kingpins, untouchable behind their billion-dollar profits and stock exchange ticker symbols.

Purchase a copy of the current issue of The Believer here, and subscribe today to receive the next six issues for $48.