“I think I’d hate any book where the author makes themself the hero. That’s not true. If you’re someone like Malala, you should definitely make yourself the hero of your book. But if it’s me whining about not having as many fans as Neil Gaiman? No.”

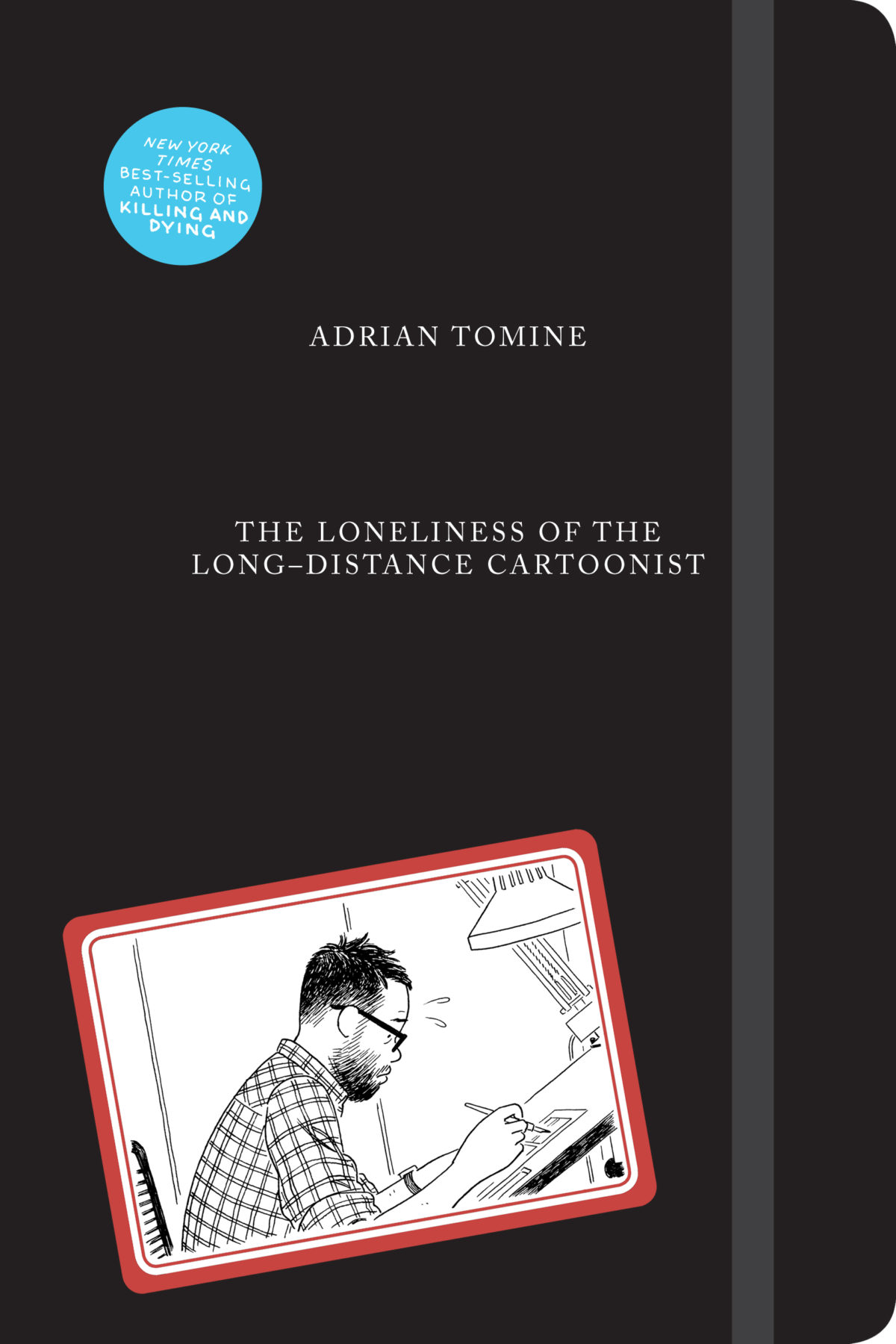

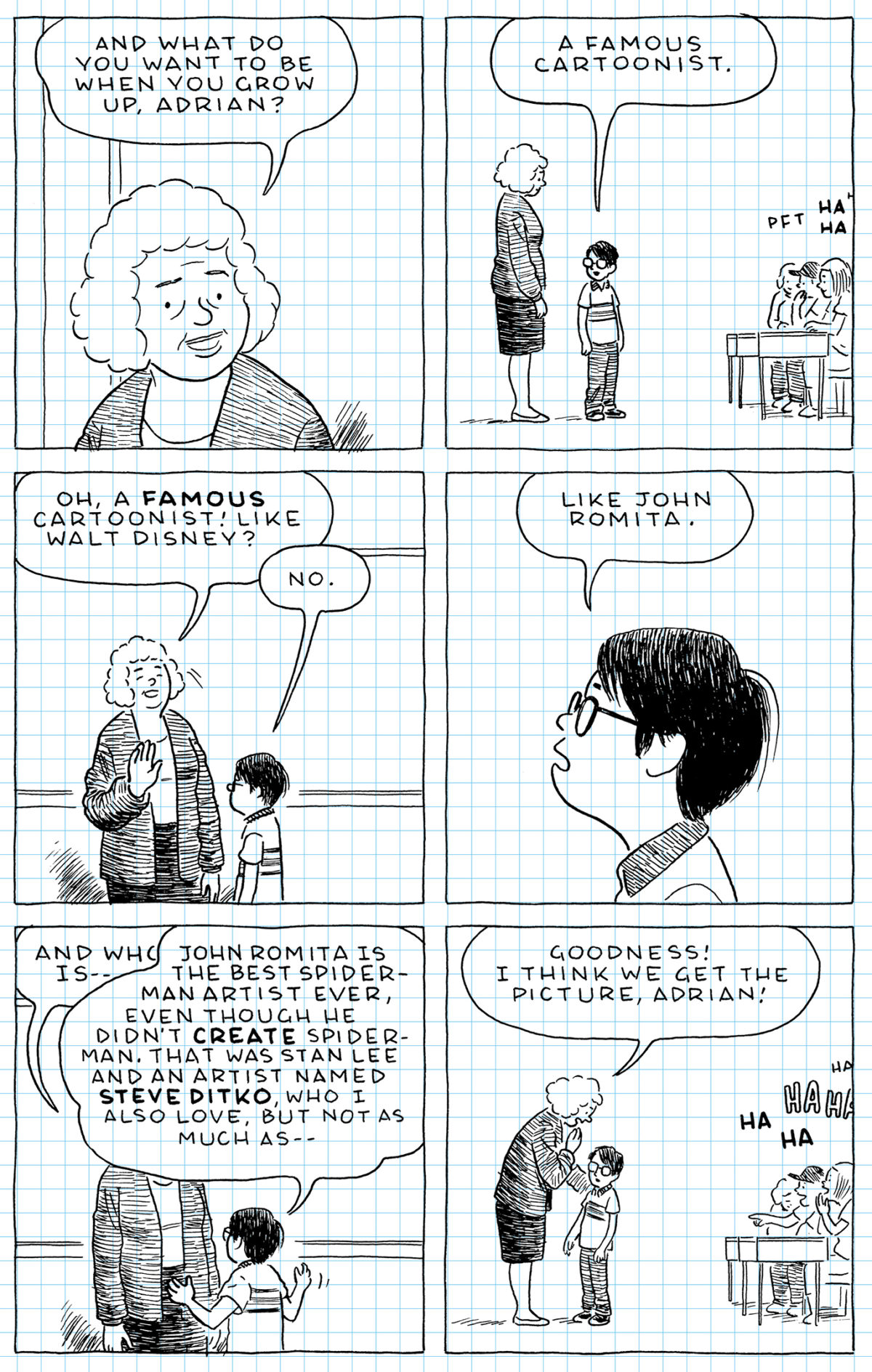

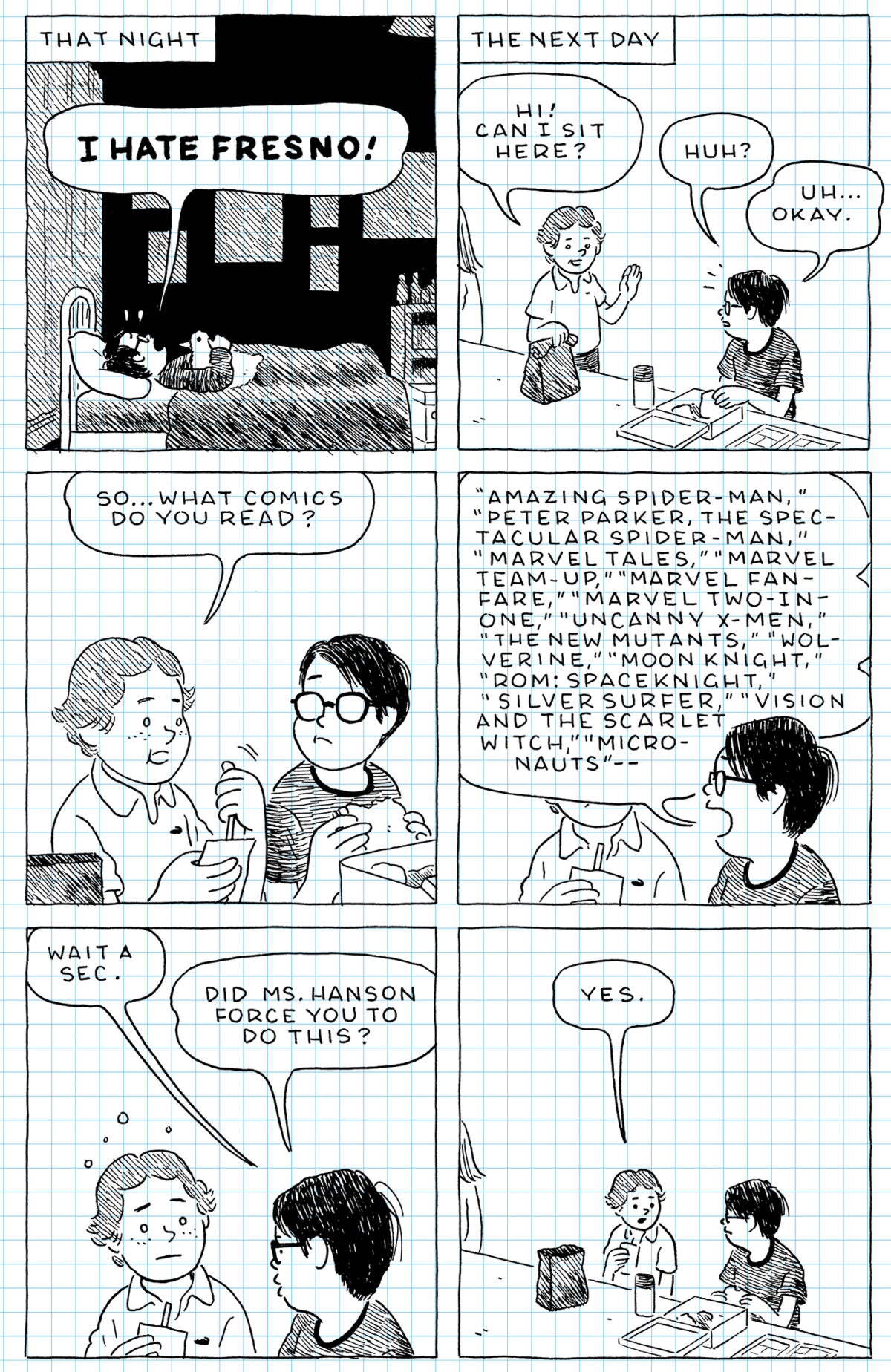

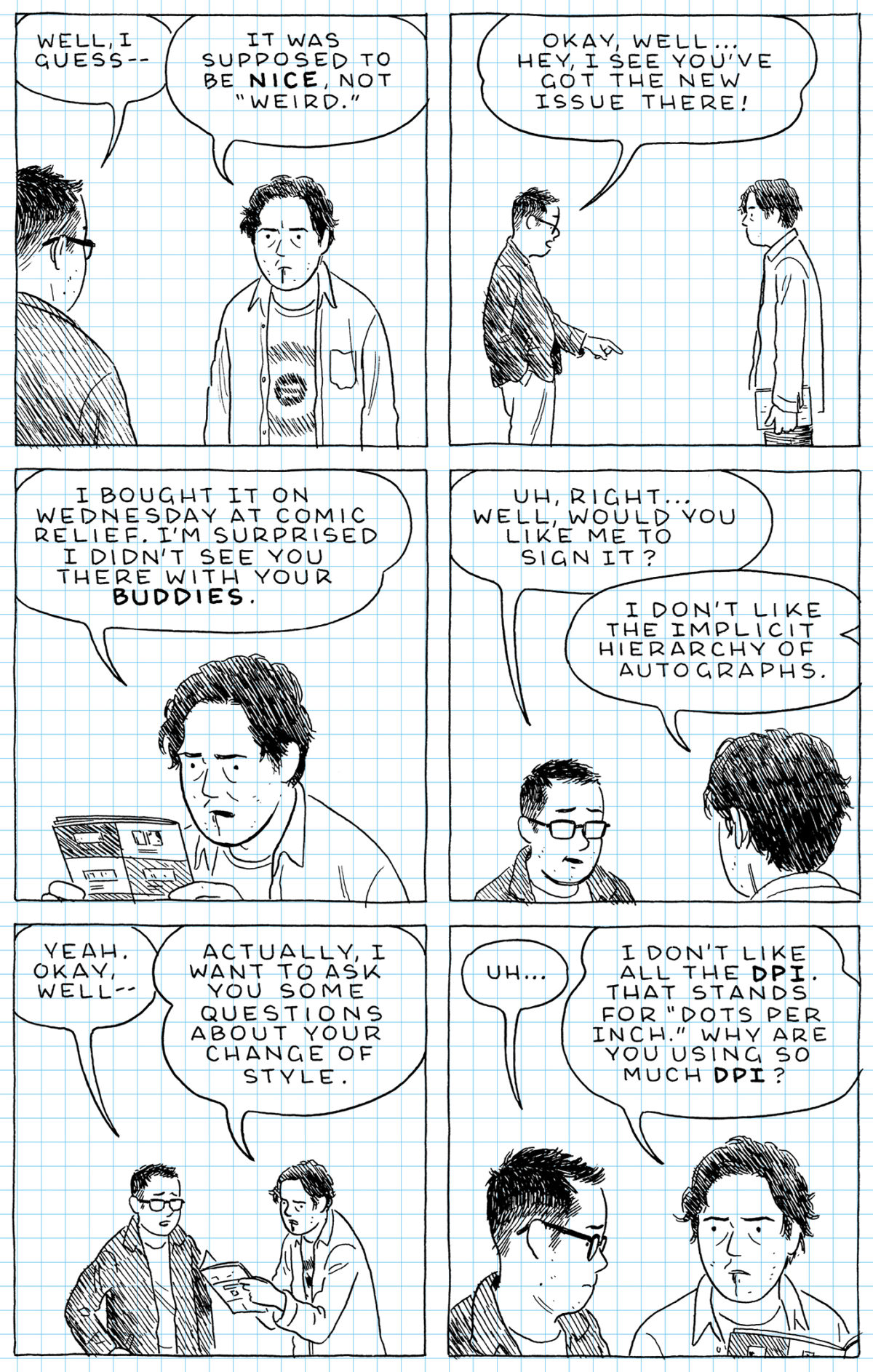

Originally known for his 1990s serial minicomics Optic Nerve, graphic novelist Adrian Tomine has become widely recognized for his covers of The New Yorker and artwork for bands Yo La Tengo and TV on the Radio, apart from continuing to publish his comics. In his newest book, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist (Drawn & Quarterly), Tomine takes us on a short tour of his past, from being a bullied kid in 1982 Fresno to being a dad of two girls in 2018 Brooklyn, with vignettes of the sometimes-uncomfortable and most-times-fortunate stepping stones along the way of his rising career, a dream job evolved from a “childhood hobby.” Drawn as the raw scaffolding of ink sketches in a notebook, the stories Tomine tells as fragments of a memoir range from embarrassing and sympathetic to comical and heart-wrenching, maintaining the simple beauty of a short story’s brief arc—and sometimes “unresolved” ending—that has become something of a signature narrative device in Tomine’s work.

—Shelby Shaw

THE BELIEVER: There’s a beautiful circularity that’s revealed near the end of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, which I don’t want to give away, but I’m curious to hear you talk about the genesis of this project. It’s printed as a facsimile of a graph-paper notebook, with your hand-drawn panels of expertly inked outlines and shading, and a faux price sticker on the back cover. Did you start this project with the vision that it would be completed as an object like this, an artifact?

ADRIAN TOMINE: I had the idea for the book design as far back as I can remember. It probably came to me hand-in-hand with the idea for the book’s contents. It just seemed like the obvious way to present this material, especially given the book’s ending. I think I also just feel a certain obligation to make books that are beautiful—or at least, interesting—objects… things that make the most of the non-digital experience that bibliophiles like me always rhapsodize about. And if I’m being honest, I think it was a slightly self-protective choice. I knew I was going to be drawing this book in a looser, less polished style than previous, and I wanted to signal to readers from the onset that this was a deliberate decision, not an erosion of my drawing abilities as I descend into old age.

BLVR: Some people have reservations about using the term “memoir” to label their personal nonfiction writing. Given how candidly you portray yourself, how do you think of the book?

AT: Well, keep in mind that I now occasionally refer to myself as a “graphic novelist,” even though it’s a term that I’ve always thought was equal parts pretentious and stupid. I’ve long ago given up on controlling the terminology, and I’m just grateful that anyone wants to talk about my work at all. But in terms of this particular book, I think it fits the technical definition of a memoir perfectly. I guess the problem now is that the word “memoir” has a lot of connotations, so some readers might be waiting for the part where I have an epiphany and travel the world and find myself.

BLVR: You start us right off with snapshots of the criticism and tormenting you first received as a kid in Fresno in 1982, followed by arriving at Comic-Con in 1995 and being handed the review in The Comics Journal which bluntly referred to you as a “moron.” Over the nearly forty years that you’ve been carrying these memories, did you always have a plan for using them in a graphic memoir?

AT: I’m embarrassed to say “yes,” but it’s the truth. Even as a kid, I was enough of a narcissist to imagine these kinds of scenes of torment replayed in a comic or a movie, either for laughs or sympathy. It was probably a more vindictive impulse when I was younger, and now it just seems like a good way to give even the negative parts of my life some kind of meaning, or to take control of them. For a long time, whenever something bad would happen to me, some well-meaning friend or family member would invariably say, “Well, it’ll be good material some day!” And usually I’d laugh and agree, but inside I’d be seething with rage and thinking, “That doesn’t really help!” But I guess it turns out they were right!

BLVR: Do you think you’ve become more self-conscious in seeking out material from your life that you can use in your books? I’m reminded of how some people will go somewhere or do something specifically so that they can post about it on social media later.

AT: God, I hope not. At least, not in terms of the kind of material in this book. I’d hate myself even more than I already do if I ever found myself doing that kind of thing. I think this mode of cartooning needs to have an unshakeable foundation of truth, otherwise the reader just won’t follow along or believe or care. I don’t think those kinds of anecdotes could really be sought out, anyway. What would I do? Intentionally orchestrate a bookstore event with a weak turnout?

BLVR: A good point. It takes a lot of courage—but also assuredness—to make art about our personal flaws, let alone the negative opinions and experiences of the field we’re in (to say nothing of the other people involved too). Did you ask other cartoonists for advice as you were making this book, or show anyone drafts to gauge their perceptions of a particular story you were telling?

AT: The only people who read this book in progress were my wife and my older daughter, and neither of them had much feedback for me until later in the story when they started appearing as characters. But anyone who knows me well enough will tell you that a lot of these anecdotes are old news because I’ve told them so many times in person. I think a lot of the editing process really happened over the years, like at a dinner, where I’d tell a variation on one of these stories and then take mental notes on how it went over. Sorry, friends, but you’ve been an unwitting part of my “workshopping” process for years.

BLVR: When working with real people as characters, how important is it to you that their drawings maintain a level of recognizable resemblance with their actual selves? Do you ever struggle with capturing likeness in your drawings?

AT: There were a lot of calculations and judgment calls. Some of the characters I tried to draw as accurately as possible, even down to their clothing, or their posture. But there were other people who I felt an obligation to obfuscate, particularly some of the less flattering portrayals. But that’s already led to some funny responses. Just today I heard that someone is guiltily identifying himself as one such character, and he couldn’t be more wrong. Maybe he’s thinking of some other incident that I’ve forgotten? I don’t know.

I do sometimes struggle with likenesses, but this simplified style of cartooning makes it a lot easier. The hardest thing is an illustration assignment where they want a very realistic portrait of a very well-known celebrity, with no cartoon-y exaggerations. That’s when I start losing my mind, because a line can be off by like a millimeter and it makes a huge difference. There are certain celebrities that I now hate just because I had such a hard time capturing their likeness.

BLVR: You name a lot of people—and also redact a lot of named people—throughout the book, whether they were in a story as an ally or as a less-than-friendly memory. Do you feel like you wrote The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist for one audience in particular, such as other cartoonists you encountered over the years, your fans, even your ex-girlfriends and childhood bullies?

AT: Starting with my previous book Killing and Dying (2015), I’ve tried to eradicate the idea of any audience at all, as much as possible. I realized that I’m basically trying to trick myself into thinking I’m a teenager again, drawing comics in my bedroom purely for the enjoyment of making them. That’s how I started out, and as the years passed, and my little childhood hobby started to evolve into a career, I found myself getting paralyzed with self-consciousness. There’s even a part in the new book where Terry Gross comments on this. I was so afraid of how the work would be received, that it became hard to produce anything. So this new book was basically created in secrecy. I didn’t submit a “pitch” to my publisher or anything like that, and in fact, I didn’t really tell anyone about it until I was at least halfway done. Especially with such personal material, it helped for me to know that no one was expecting it, no one had paid for it, no deadline was hanging over me. I actually made notes in my sketchbook to the effect of, “If this sucks, just throw it away and start something else.”

BLVR: Did you debate with yourself about what to do with it once you were done? Or were you decidedly going to put it into the world at large by then?

AT: No, I’m modestly self-doubting only to a point. By the time the book was actually done, I’d committed to it. My publisher had already started making plans for it, and they were waiting for it. The most work I’ve ever thrown away, at least in recent years, was a complete story for Killing and Dying, and even then, I probably could’ve salvaged it.

BLVR: Between the first scene in 1982, up until the last one in 2018, you typically share only one story per year, maybe two in different cities. What was it like for you to go through so much past and select the final scenes for this book? Did you have a hard time sifting through memories and paring it all down, or remembering what happened? I was moved by all the small details of every room and their consistencies: a painting on a wall, fluorescent overhead lights, little pieces of set design that you captured over decades.

AT: One of the most unexpected challenges with this book was editing myself. In the past, I was always looking for ways to beef up my books, make them seem more substantial. You know, “Can we print this on thicker stock?” or “How about some endpapers, then a title spread, then a single title page?” But with this one, I honestly felt like it could’ve been three times as long because there are so many similar anecdotes from throughout my life that I could’ve used.

BLVR: Would you characterize yourself in the book as the “hero” of this story?

AT: Can you imagine how gross it would sound if I said “yes”? I think I’d hate any book where the author makes themself the hero. That’s not true. If you’re someone like Malala, you should definitely make yourself the hero of your book. But if it’s me whining about not having as many fans as Neil Gaiman? No.

BLVR: How do you think your early career compares to that of a cartoonist starting out today? From your perspective, do you think one experience is better than the other? More difficult?

AT: I’m sure the two experiences are very different in a lot of ways, and I’m glad I’m not in some sci-fi scenario where I get to choose whether I’d rather be a young cartoonist now or then. My gut response would be to choose now, because comics have become so much more accepted in culture, and because it seems like there are so many more opportunities to get the work out there. On the other hand, I think it would destroy my mind to try to take those first steps towards sharing my work with the world in the era of social media. I really benefited from the slow, gradual process of first showing my comics to a few people (i.e., my parents and brother), then putting it in a few local comic shops, and then growing from there and taking feedback along the way. I don’t think I could’ve handled the two extremes of praise and criticism right out of the gate. It’s also worth mentioning that the early part of my career was filled with unbelievably lucky breaks, random coincidences, and a handful of people who went out of their way to help me. You can’t plan on those kinds of things, then or now.

BLVR: What was your plan if the lucky breaks, coincidences, and network never came to you? Did you always have another vision of what you would pursue if your comics career didn’t succeed the way it has?

AT: I don’t think there was ever a vision of my future that didn’t include making comics. I was open to the very real possibility that it would remain a hobby, and that I’d have to find time to do it when I wasn’t working at my real job. And for that reason, I always assumed I’d have a sort of mindless, predictable job that would facilitate that. For some reason I always envisioned myself working in a newsstand kiosk.

BLVR: Throughout Cartoonist, a recurring criticism you’ve received is that your stories end too abruptly or lack “enough” plot. I’ve always thought these two elements are strong reasons for precisely why comics as a medium can be successful though, and why I enjoy so many of them. But given the repetition of the comments, did you ever consider other formats for telling your stories (fiction or non-fiction), like stage plays or live-action serial episodes?

AT: Compared to the lifelong New Yorkers I know, I’m basically a philistine who, prior to moving here, never went to the theater, the ballet, the opera, or anything like that. So when my wife first started taking me to see plays, I wouldn’t tell her, but I kept secretly having the reaction of “That’s it? That’s what that famous play is about?” After my initial incredulity, I started really appreciating that there’s still a form of popular entertainment that doesn’t necessarily rest so heavily on things like plot or resolution or star power. I actually tried to write a TV series a few years ago, but it hit a lot of the expected roadblocks, and in hindsight, maybe I should’ve tried to write a play. And now I’m working on a screenplay, so we’ll see how that goes. The nice thing about “stepping out” and trying these other things is that it always reminds me how amazing it is that I can sit at my desk with some materials that basically cost nothing, write and draw whatever I want, and (at least so far), my publisher has been willing to put it out.

BLVR: Would you want a stage play or film to look like one of your graphic novels, or would you use live-action as a chance to totally pivot from the smooth and warm-toned aesthetics that identify your drawing work currently?

AT: I don’t know if those are the only two options. But no, I don’t think replicating my drawing style or aesthetic would be a top priority. I’ve had a lot of phone calls with people who just assume that I’d want to adapt my stories with animation, which has never been the case. I understand why someone might think that, but the truth is, I really think of my characters as real people, and have always envisioned any adaptation as live-action. I think I generally just care about the writing in my stories the most, and the artwork is almost a utilitarian thing to communicate those stories. Having said that, I think there’s a way to still nod to the look of the source material, but it’s nothing I’ve ever insisted upon when discussing possible adaptations.

BLVR: At the end of Cartoonist, you find yourself urgently reminiscing for hours about your family, and later that night you tell your wife, “I always imagined that when I was on my last legs, I’d be consumed with thoughts of the comics I didn’t get to finish.” It was your family you were consumed with thinking about instead. Was writing The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist one of those comics you alluded to having always planned to have finished in your lifetime? Or was this project a surprise?

AT: I’m not one of those people who has their whole career mapped out in advance, so I don’t think there was any specific unfinished book I had in mind. I guess I thought that when the end was on the horizon, I’d suddenly come up with all these amazing ideas and then be bummed out that I wouldn’t get to realize them. I think I’ve always had the idea of doing a big, autobiographical book, but I wasn’t sure what the focus would be. I’ve had the anecdotes that make up the first two-thirds of the book in my mind forever, and then when the stuff that makes up the last part of the book occurred, it all kind of came together quickly in my mind.

BLVR: Are there any specific autobiographical works (comics or otherwise) that have inspired you over the years?

AT: Sure, there’s a long, rich tradition of this kind of work in comics, and I’m really just weakly walking in a bunch of other artists’ footsteps. The first two cartoonists I ever met were Carol Tyler and Justin Green, both of whom were creating incredible, ground-breaking autobiographical comics before I was even born. When I was first published by Drawn & Quarterly [in 1998], almost all the other artists there were doing autobiographical work. That group of artists—Chester Brown, Julie Doucet, Joe Matt, and Seth—had a big impact on me. Even today, there are lots of great practitioners of the kind of casual, self-deprecating cartooning that I was aspiring to with this book, like Noah Van Sciver, Vanessa Davis, Gabrielle Bell. There’s something about the medium of cartooning that syncs up very nicely with autobiographical storytelling. And even though it wouldn’t technically be considered autobiographical, I’ve always been a big fan of the [Seven] Up film series, and I love that experience of seeing a wide stretch of life condensed down into little chapters. For some reason, that’s like the most moving thing I can see in art, especially when it’s real.

BLVR: Now that you’ve got a memoir and art-book object completed with this book, where are you taking your comics now?

AT: To be honest, the last four months have not been very conducive in terms of thinking up my next big comic project. Even now, I have no idea of what my kids’ schedules are going to look like in the fall, so I’m apprehensive about committing to much more than something I can work on in between homeschooling, cooking, cleaning, etc. Fortunately, I really do feel the way I describe at the end of the book. I’ll draw more comics if I get the chance, but I also feel like I’ve already pushed this childhood hobby way further than I ever could’ve imagined.