“Witches are comfortable with ambiguity, and with complexity, and with holding simultaneous beliefs, and living in a mythopoetic space. I think that’s something that needs to be reintegrated into our culture, which is so binaristic, and claims naming rights to everything. It gets to name our gender, it gets to define the perimeters of what we get to be in this world.”

Magic:

Is anything that stands outside of what the modern mind thinks of as rational

Is contingent on the time and place it was created

Never really goes away

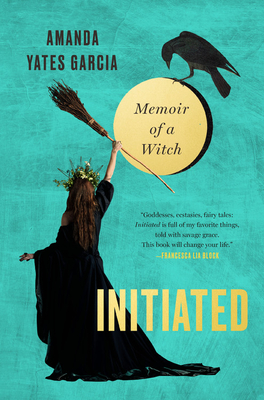

When I interviewed Amanda Yates Garcia, the Oracle of L.A. and the author of Initiated: Memoir of a Witch, it was sunflower season in New York City. I was preparing to fly to Cassadaga, Florida, known as the “Spiritualist capital of the world.” The sunflower is the symbol of Spiritualism, and sunflowers were everywhere: across the street from my apartment, bending over my bus stop, outside every bodega.

I read this as a sign. “Everything around us is constantly communicating, singing of its history, its composition, its desires and experiences,” Garcia says in Initiated. “The Universe is made of information. Signs appear when, out of the universal hum, we pay attention to that one voice: Spirit’s serenade just to us.”

The Universe was calling me on a mission. Initiated seemed to reiterate this, as an expansive exploration of alternative ways of seeing, knowing, thinking, and living. “Those signs mean something,” Garcia says. “But if we ignore our signs, their meaning collapses.”

Initiated is a feminist history of witchcraft, a work of critical theory, an activist manifesto, a personal mythology, and a memoir following Garcia through her upbringing as a generational witch, her journey into the underworld of poverty and sex work, and her return to her body, discovering her power through art and witchcraft.

“For many witches, their first initiation drags them into the underworld,” she says. Garcia’s own underworld was “a labyrinth of sex and power and patriarchy.” Her story tells of childhood neglect and abuse, sex work, mind-altering drugs, and toxic relationships. Her return, like her descent, happens through the medium of her body.

Now it’s Scorpio season, and Persephone is again descending into the underworld. On her podcast, Strange Magic, which she co-hosts with art witch Sarah Faith Gottesdiener, they describe this time of year as one of “potent transformation” and harvest—reaping the rewards of our work.

They also, in a previous episode, talk about “binding,” “A spell cast on another person or group with the intention of preventing them from doing harm.” In 2017, Garcia gained recognition when Fox News’s Tucker Carlson invited her onto his show to explain the binding spells she and other witches had been performing against Donald Trump, each month on the waning moon. Garcia described binding as, like any other spell, “a symbolic action used to harness the powers of the imagination and achieve a tangible result.”

“My ultimate aim is that we protect the people that we love from having harm done to them,” she said. “But in the meantime, I think what’s really important is that we create a sense of solidarity and empowerment within the people who are participating in the spell, to galvanize them toward action.” Initiated, too, is a galvanizing work—a reminder that to write is to cast a kind of spell.

Today, Garcia is a performance artist and a full-time witch, healer, and teacher. She has lectured on witchcraft at UCLA, Cal State Pomona, and UC Irvine, and has performed public rituals at MoCA Los Angeles, LACMA, the Getty Museum, the Hammer Museum, and MoCA Tucson.

We talked over the phone about witchcraft as a queer feminist practice, the similarities of witchcraft to mysticism and metaphysics, Garcia’s creative and activist practice, her experience as a sex worker, her process of writing Initiated, and finding herself as a witch.

—Sarah Gerard

I. Breakthroughs and Bonding

THE BELIEVER: I thought maybe we could just start out talking about what kinds of different energies might be infusing this conversation. I don’t know if you’ve looked at the sky today or pulled some cards of your own, or set any intentions.

AMANDA GARCIA YATES: I can pull some cards right now.

BLVR: Okay, cool.

AYG: And I’ll pull a rune to tell us how to focus our energies for the conversation, if that sounds good to you?

BLVR: Yeah.

AYG: First off, I got the Dagaz rune. It means daylight, daybreak, breakthrough. An opening after a long period in the dark, the sunlight emerges. Today is a lunar eclipse, and eclipses can also indicate breakthroughs, because they represent rupture and interruption, a time when the ordinary order of things is turned upside down. So it’s a breakthrough kind of a day, maybe we should focus on that.

Dagaz represents an awakening, shaft of light that comes in and illuminates a landscape that was once unnavigable and dark. It’s a rune calling for radical trust, you have no choice but to throw yourself into this new awareness. Dagaz also encourages us to recognize our achievements, and consider our next steps. We’ve entered a new stage, how do we want to perform in this new scene? The Dagaz rune and the eclipse give us a lot to work with in this conversation.

BLVR: Publishing a book is very much like that. It feels like a breakthrough.

AG: Yes it does, it did for me anyway. So many of my ancestors wrote books, but none of them were published. Completing Initiated and publishing it feels like I broke a family curse. I eclipsed it!

Okay, wait, I’m going to pull a card, too. Yay, the Three of Cups! Also called “bonding,” in the version of the deck I’m using. I use different decks, but right now I’m looking at the Daughters of the Moon deck, which is a queer feminist deck made a few decades ago in the Midwest. The Three of Cups represents friendship. It usually depicts three women dancing together, holding cups, toasting them above their heads, draped in garlands of roses. There’s a celebratory quality to the card. Maybe that’s something we can address, how witchcraft is a way of bringing—women in particular—together.

BLVR: Do you think it’s significant that you used that particular deck?

AYG: You know how I always think of it? Remember that song “…Baby One More Time,” by Britney Spears, super catchy, wanna dance to it? Well, Travis, that Scottish indie band from the 90s, did a cover of it. It’s the same song, but Travis’ version teases out the romantic longing, almost like it’s a poetic excerpt from the Sorrows of Young Werther or something. The words and tune didn’t change, but the slower tempo foregrounds aspects of the song hidden beneath Britney Spears’ catchy riffs.

The same happens with the tarot. The cards don’t mean radically different things in different decks, the symbols and basic meanings are the same. It’s just that one deck might highlight the playful aspect of the Three of Cups for example, while another deck might emphasize the shadow side: periods of celebration are usually followed by hangovers after all, and periods of abundance rarely last. The knowledge of that is built into the card itself.

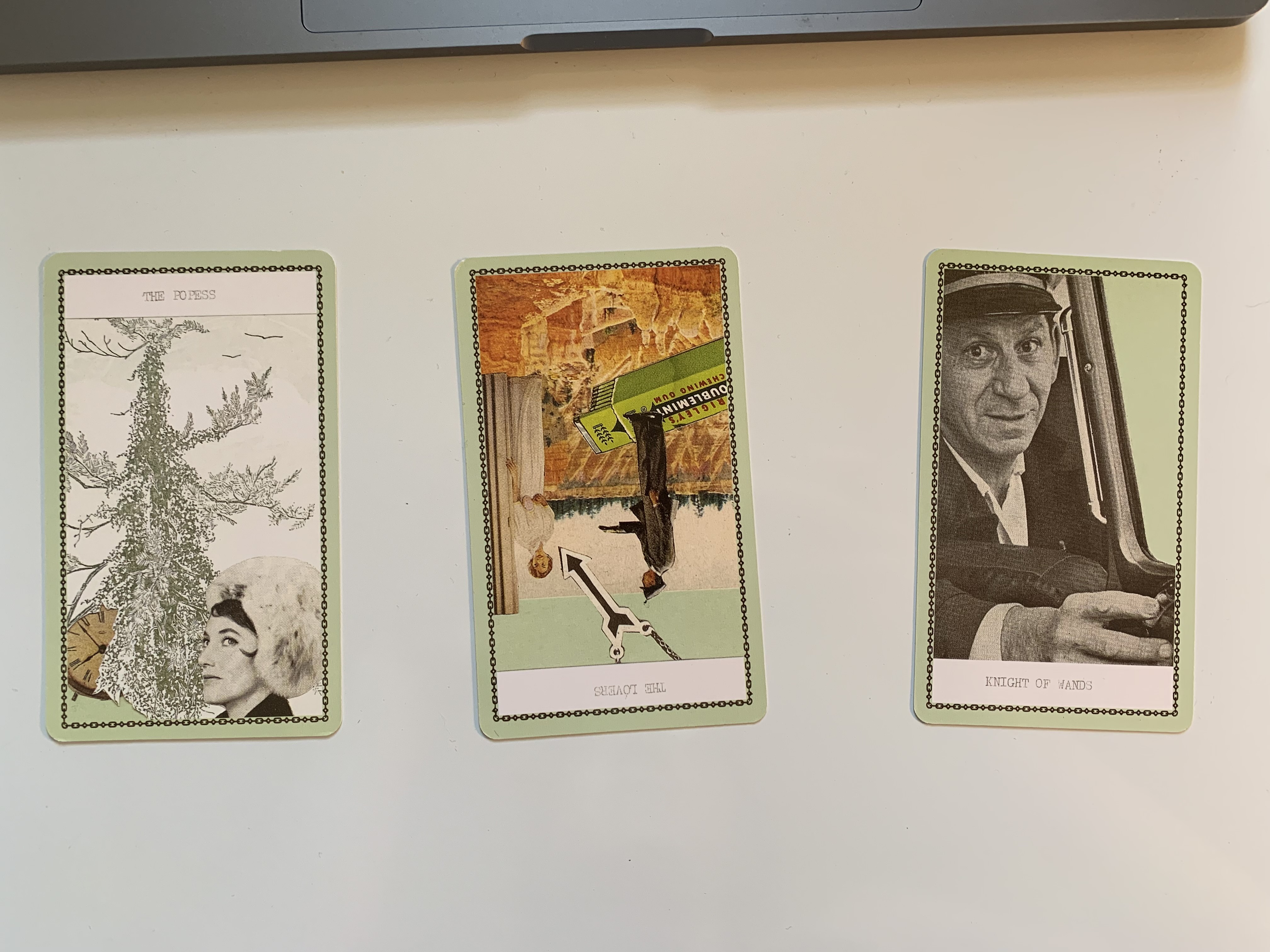

BLVR: I only have one deck because I’m kind of starting out—I was raised in the New Thought Movement, which is a metaphysical and mystical tradition, but tarot was always something kind of on the periphery, that my friends were doing, until recently. So I only have one deck, but it was gifted to me. It’s this really odd collage deck, called the Frau Grand Duchess Tarot. It’s a self-published deck that you have to buy directly from the artist.

Right before I called you, I pulled some cards about our conversation. I’ll just text them to you now.

AYG: Those are beautiful.

BLVR: The Empress [also called The Popesse] is the left and the Knight of Wands is the right. The question was, “What should I talk about with Amanda today?”

AYG: The Empress to me signifies creativity and the creative process. That would be our point of entry. And then The Lovers card—it’s funny because in my podcast we talk about The Lovers card as the queerest card in the deck, because it’s about this blending or liminal space, an escape from the binary, a “yes, and…” kind of energy, about improvisation, and paying attention to the third thing that is created when people form a relationship.

BLVR: Cool.

AYG: The Lovers card embodies some of the spirit of witchcraft. Both are queer and playful. Improvisational, but also rigorous, both are all about creating relationship, creating intimacy with the world. That’s something that a lot of people don’t understand about witchcraft. Some people might think, “Oh that’s ridiculous, how can people call themselves witches? Nobody flies through the air on brooms.” It’s like they think we’re trying to be Harry Potter or something, like we’re playing make believe. What those people don’t understand is that witches are comfortable with ambiguity, and with complexity, and with holding simultaneous beliefs, and living in a mythopoetic space. I think that’s something that needs to be reintegrated into our culture, which is so binaristic, and claims naming rights to everything. It gets to name our gender, it gets to define the perimeters of what we get to be in this world. “Do you want to be a doctor, a lawyer, a waiter, a garbage collector?” Being a witch isn’t presented as an option. Our sense of what our world can be and what we can be is limited by the options presented to us, we have to be some kind of worker. We have to define ourselves in relation to capital somehow. We should be “rational” and reasonable all the time, because experiencing the world in a mythopoetic way decreases our productivity and is not conducive to the generation of capital.

One of my favorite writers, a Jungian analyst by the name of Ginette Paris wrote a book called Pagan Grace, and in it she has a long chapter about Dionysus, who corresponds to the witch’s god, Cernnunos, the Horned God of nature and wildness. As Dionysus he’s the god of women and also ecstasy.

BLVR: A very sexy god.

AYG: He represents the energy of chaos and revolution, and so much more. But in the book Paris talks about, and as a witch I very much identify with this, how people are always asking her, “But do you really believe in these gods?” And she says, “Well, that’s like asking me, do I believe in the collective unconscious, or do I believe in transference in a therapeutic setting, or do I believe in repression of emotions?” None of which you can see or even test for, really.

BLVR: Right.

AYG: The collective unconscious is something that most of us talk about. It’s ubiquitous. We act as if it is real. But it isn’t necessarily real in the sense that we can touch it or prove it, but it’s a concept that brings us a sense of meaning, and it’s interesting; it’s useful. When someone asks a witch if she really believes in the gods, she might respond, “Do you believe in the Fibonacci sequence?” If we were looking at a shell we might see the Fibonacci sequence inside that shell, and say, “Here is an example of the Fibonacci sequence, here in the way this shell spirals.” But the sequence itself is a concept, an invention, just as the gods are an invention. But that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. Dionysus exists in nature, he’s a force that permeates wild places. He appears whenever we experience ecstasy. What I’m getting at, bringing it back to our point of departure, the Lovers card, and the queerness of witchcraft, is that for witches, all of this is going on beneath the surface of our discourse and it’s something I wish was talked about more often in all the “Everyone’s a witch now,” articles you’re seeing everywhere.

Okay, so what’s next? Ah, yes! You drew the Knight of Wands. Knights are all about action. Knights execute the action of the king. So they’re all about moving forward, advancing, taking steps, and Wands are the tools of will. With our wands we point to something and say, “this, this here is what I want to transform.” As a phallic symbol, the suit of wands is clearly about passion, and also power. Ultimately, wands represent the creative impulse.

If we look at your spread, the Empress, the Lovers, and then the Knight of Wands, we see how the tarot is elaborating about the creative process. Beginning with the unbridled creative force of the Empress, queering it and breaking down our own binaristic impulses and allowing ourselves to go into uncharted territories with the Lovers card, and then doing the work of taking our work out into the world with the Knight of Wands. But I do have to say that if you’ve been using this deck as a learning deck, I can tell you that this will not be an easy deck to learn from.

II. “Magic is my tool of resistance.”

BLVR: Can you talk about how storytelling worked in the structure of your book, Initiated: Memoir of a Witch. When I teach writing, I encourage my students to look for patterns in imagery and also action. I think so much of what you’re doing in your book, as a character, if you can talk about yourself as a character in your own memoir, is letting the symbolic patterns that you see emerging in your everyday life guide your action. Or maybe the story emerges out of your process of learning to do that.

AYG: Part of the challenge of writing a memoir is finding the narrative arc in one’s life, which is made up of an infinite number of small moments that may or may not be significant to the denouement of the work. Life doesn’t follow a narrative structure, so you have to go back and sift through it. You’re panning for gold, sifting away all the silt until you’re left with these nuggets of meaning that you find, or hope to find, and then you have to melt them down and pound them out, you have to make them form a relationship.

Initiated started off as three different books. One was a magical how-to book, like, “This is how you do spells,” using illustrations from my own life. Then there was a book of poetry, all about the magic of place. I still want to write that book. Then there was this straightforward memoir, which kept popping up and getting in the way every time I tried to write anything: my story would just kind of enter the room like the Ghost of Christmas past. I have this intense family legacy that wanted to be addressed, about the women in my family struggling to find their voices, or being able to believe in the worthiness of being heard, and not just self-destructing in the process of trying to escape from beneath the jackhammer of patriarchy.

And so, as any good witch would do, I went to Hecate, the goddess Hecate—who is the goddess of witches, and the goddess of the crossroads, and the goddess of the underworld—and she led me back along the shadow roads of my life, where I started to collect things, and make sense of the scraps that I found. For instance, in the book there’s a scene in my childhood where this crow falls at my feet, dead. Later, when I was eighteen and was essentially having a nervous breakdown, or kind of a shamanic break, a shamanic call, in my late teens, crows were appearing everywhere, I kept noticing them on the street, as if they were following me around. And of course crows are the familiars of Hecate, of any underworld goddess, because they guard the gates of the underworld and eat the carcasses that are left behind. Making the connection between all these crows in my life, I felt like I was gathering breadcrumbs, leading me to these goddesses of the underworld, Medusa, Hecate, the Morrigan, but instead of finding a monster at the end of this trail, I found a way to reintegrate the villainized parts of myself. These goddesses came to me and showed me how to navigate the story—which, for a lot of writers, can really feel like you’re wandering through a labyrinth trying to find a narrative and it keeps disappearing around the hedge.

And so, as any good witch would do, I went to Hecate, the goddess Hecate—who is the goddess of witches, and the goddess of the crossroads, and the goddess of the underworld—and she led me back along the shadow roads of my life, where I started to collect things, and make sense of the scraps that I found. For instance, in the book there’s a scene in my childhood where this crow falls at my feet, dead. Later, when I was eighteen and was essentially having a nervous breakdown, or kind of a shamanic break, a shamanic call, in my late teens, crows were appearing everywhere, I kept noticing them on the street, as if they were following me around. And of course crows are the familiars of Hecate, of any underworld goddess, because they guard the gates of the underworld and eat the carcasses that are left behind. Making the connection between all these crows in my life, I felt like I was gathering breadcrumbs, leading me to these goddesses of the underworld, Medusa, Hecate, the Morrigan, but instead of finding a monster at the end of this trail, I found a way to reintegrate the villainized parts of myself. These goddesses came to me and showed me how to navigate the story—which, for a lot of writers, can really feel like you’re wandering through a labyrinth trying to find a narrative and it keeps disappearing around the hedge.

BLVR: I’m in the sixth or seventh revision of my novel right now, which originally began as a short story, and it’s just morphed into this complete, kind of like Hecate, this beautiful monstrous being. And it does often feel like a trip into the underworld.

AYG: Exactly, where you’re moving by torchlight through these dim hallways, and you don’t know what’s around the corner, and you don’t know which figures are monsters and which are guides. One of the things that appeals to me so much about witchcraft is that these figures, the goddesses, and the stones we use, the tarot cards, the candles, the symbols, they’re all tools, they’re all guides, they’re things we work with that help us find a way to navigate a world that is antagonistic to our nature. Witchcraft helps me find a way to thrive in my exile here in capitalist consumerism. And in fact, witchcraft transforms what I experience as an exile of the world—a feeling of Otherness—into a feeling of intimacy with that world or the “other world”, a more beautiful world, right beneath the ordinary one. The world of the imagination, and the world of beauty, the world of connection, the world of queerness. That’s the world that I want to live in, and yet I found myself born into a world that was restrictive and repressive, ugly and consumerist and patriarchal, always trying to get rid of us exiles, trying to smoosh us down and make us give in, trying to get rid of the things that we hold sacred. And so magic then is my tool of resistance to that, because magic is a tool of re-enchantment.

I feel like The Empress card that we spoke about in the beginning: The Empress is the world that exists beneath the ugly world of capitalism. The Empress is the jungle, she’s endless bounty and life force, she’s dolphins and parrots and panthers and spiders and cockroaches and orchids and Lapuna trees and water dripping from the leaves, and she’s just creating, creating, creating. She’s nature, she’s the essence of the life force and I want to be with her, I want my life to be devoted to her. The book describes my attempts at resistance, not wanting to live in this soulless Kmart nation. It describes how these guides, my mythological allies, came to me and helped me, and led me, and got me to a place where not only do I feel powerful, but I feel like I’m thriving, and I feel like there’s this awakening, this Dagaz moment, happening in other women too, and other queer people, the people who also want to live in the world of the Empress. It feels like now is a really exciting time because of that, because we have the will to create that.

III. Persephone

BLVR: You mentioned not wanting to live in this soulless Kmart of a world, and it reminded me of the scene in your book where you’re making your hundredth tuna salad sandwich of the day in this miserable coffee shop, and you just had this complete freakout, like a Jerry Maguire moment—and that breakdown is what led you into sex work. Something that’s really interesting to me about this story is how much of your journey was felt through the body, or was a journey into—well, first away from, and then back into, your own body. You use the image of Medusa’s decapitated head, and the mind and the body having been severed—but she continues.

AYG: For me witchcraft is a religion of the body, which stands in stark contrast to most of what we might see in the Abrahamic traditions. Witchcraft is about pleasure and desire, it’s embodied spirituality. Spirit is eminent in witchcraft: it comes forth from the body, from the planet, from the earth, from our bones. I was brought up in that because my mother practiced it, but simultaneously bodies make us vulnerable. My mother had been abused, and I too had been sexually abused. And so as a young woman, I just thought this is the world we live in: “[abuse] happens, this will happen, this happens to everyone, and so I must accept it as my lot. I have to just deal with the reality of that, and try and find a way to make it work for me.”

But that break you’re talking about happened while I was working at a sandwich shop, and I had this painful satori moment where I recognized the monotony and pointlessness of being in that place, and realized that I might not ever be able to get out if it, because I was barely able to scrape by enough money to pay my rent, much less change my circumstances. In that moment, I saw my days stretching on and on and on at the sandwich bar forever, people asking me for the bathroom key until the end of time. It wasn’t so much that the work itself was horrible. It was the feeling of being trapped in it, that I could see the outside but I could never get there. At that Dagaz rune moment, a light broke through and I was compelled to make a radical shift. One of the girls I was working with was doing sex work on the side, and she was like, “You should try it.” And then when I did, I mean there is something so—like when you were a little girl, did you fantasize or play in a way about being older? Or being this sexy woman who was a seductress of some kind?

BLVR: I think every kid does. My friends and I would make our Barbies have sex. Every kid engages in fantasizing about what it might be like, and what “sexy” is. Much of that is informed by television—I mean probably now the Internet, social media, or wherever kids are getting information about what’s sexy. It’s just a message that you receive, because as a child you’re so open, and everything you see for the first time is just is “how it is,” that’s how it is in the world. There no variety in what you’ve seen, yet. You don’t know anything different.

AYG: Yeah, so when I was younger, or in my teens, like a lot of girls and feminine-identifying folks who play dress up, the idea of being seen as this powerful, sexy, irresistible woman was seductive for me. And I think, in that scene [in the book, in which she’s engaging in sex work for the first time], I talk about how I imagined stripping would be like Jennifer Beals in Flashdance, which I remember catching glimpses of as a child, and she was so intoxicatingly beautiful. And thinking that I could be that, but not really understanding that [performance in the movie] was for the male gaze—

BLVR: Yeah, exactly.

AYG: And that in reality it was not an accurate depiction of sex work. I want to make clear that I don’t believe that there’s anything at all wrong with sex work, or sex workers, but what I do know is that we live in a world that punishes sex workers. And that’s the thing that made doing that work so damaging for me: not that the work itself, but the way that I was punished and fetishized simultaneously. As with so many sex workers, I was so young when I got involved, it was hard to understand all of the complicated, and often very painful, dynamics that I was suddenly interpolated into.

For me the myth of Persephone always resonated for me, even as a kid I was obsessed with it. In the myth she’s a heroine abducted into the underworld, but eventually she becomes its queen. There in the underworld she’s able to locate her power, her ability to do meaningful work, to transform the world according to her desires, to find her voice, to find her agency.

Witchcraft is so much about recognizing ourselves as agents, not victims at the mercy of hostile forces. What was always so weird to me about working in the sex industry was that the men that I was working with always would be like, “How does it feel to be so powerful?” They would always ask me, “I bet it feels really good to just be able to control and manipulate men like this.” And I would think, “Are we on the same planet?” The sex industry is controlled by men who manipulate and exploit women, and then they tell the women how manipulative they are for being there. Once I got pulled into it, it was very difficult to find a way out of it again [for] a variety of reasons, but mainly because in one hour I made the same amount of money that I made in a 40-hour workweek at the coffeeshop. It took a lot from me but it also gave me a lot of time to do the things that I wanted to do with my life – unfortunately, most of what I did with that time was recover from the stress of working at the job.

My clients wanted so much emotional labor from me. They wanted me to act like their girlfriend, they wanted me to console them about their mother, they wanted me to make them feel better about their relationships with their children, and then they wanted to project all of this insecurity about their own sexuality onto me and have me smile and twerk while they did it. And I was eighteen years old. I was just not equipped. Yet that question about “what’s it like to have so much power over men” was a daily occurance. The people we oppress in our culture, the people that we punish—are so often treated like demons and monsters by the very people who are harming them—kind of like the witches in the inquisition. And now Trump comes out with his ridiculous accusations of being the subject of a witch hunt, and here again, the person causing the harm is behaving as if he were the victim.

I feel like witchcraft has always operated in the liminal spaces, outside of the ordinary channels of power under white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. For me, it has a liberatory potential and helps me cope with the fact that, I live in this world, whether I like it or not. Hekate asks me, “Now given the truth of what is happening, what do you want to do here?” Rather than just feeling like I was at the mercy of the world, witchcraft helped me open my view of what was possible to become, in the sense that I was able to not just see myself as a stripper or a sex worker or a sandwich maker, or someone who aspired to be a writer, but that I could be my own frame of reference, that I could form my own standards for what I thought was right and good and beautiful, and what I wanted to be.

One of the things that people are really attracted to, or that we all can see in popular culture, is that witches are very definitely sexualized all the time. Like for instance, there’s this great book by Kristen J. Sollée, Witches, Sluts, Feminists. Have you ever heard of that book?

BLVR: No.

AYG: It’s an academic book—she teaches at The New School. In it she talks about how witches are portrayed as these old, sexless hags, or these nymphomaniac, young seductresses. But even given her appetites, witches are not defined by their relationship to men, which is very unusual in the history of western literature. We have wives or queens or mothers or daughters, but they’re always defined in relationship to others. But a witch is a powerful agent in her own right. She’s a heroine without need of a prince.

BLVR: I was going to say, oftentimes she’s a woman living alone in the woods. She’s kind of how I think of writers: these solitary conjurers. Or she’s among other women.

AYG: That’s so exciting to think about, actually, that you mention that, because most of the time, we’d imagine a woman would be afraid to be alone in the woods. But a witch is at home there.

BLVR: She’s alone and she’s not, because she’s in nature. Everything around her is animated.

AYG: Right, and she’s working. She’s got her animal familiars and she’s got the spirits that she’s working with. Even the plants and the trees are a part of her world, she knows their mysteries. So she doesn’t have to be afraid. In fact, people are afraid of her! Of what she can do.

There’s something extremely compelling about the witch then, if you feel like the world that you were born into is one that is haunted by rapacious authority figure intent on causing you harm, [like the one] that was haunting my mother when I was a child. Most women grow up cautioned constantly that, “There’s this scary man who’s going to hurt you if you walk alone in the dark, or get drunk or smile too much or travel by yourself or…” But the icon of the witch doesn’t have to be afraid when she is alone. Of course, real life witches are just as vulnerable as anyone else, but aligning myself with the mythological witch gives me the strength to stand up and keep going.

IV. Mycelium

BLVR: Earlier, I thought of a passage from the book, from when you’re in Amsterdam. You talk about how magic shows up more, or maybe we notice it more, in times of chaos. I’ve been interviewing people in other schools of mysticism and metaphysics, and a belief of the Spiritualists is that everybody is psychic, but with practice we get better at it. As children we’re very aware of our abilities, but as we grow up, we’re taught to think rationally, which is kind of in line with your own story too, right?

AYG: Right.

BLVR: There’s a period when you were reading only male Existentialists, I remember.

AYG: Yeah.

BLVR: And you had to kind of relearn this skill of intuition. The magic was always there, but in those times of chaos you came back to it, began to notice it more.

AYG: Well yeah, it’s often said in scholarly articles about magic, that in times of social upheaval magic becomes more popular within the community.

BLVR: Which I think is true in our culture today. We’re seeing it in all these different forms.

AYG: Sure, as fascism rises in our culture and people turn more and more to the occult or other forms of magic in order to find agency in a system that is failing them, or actively harming them really. However, I also think that magic, exactly as you said, never really goes away. People talk about the New Age, but when exactly is this new age we are talking about? Are we talking about Esalen in the 60s and 70s or are we talking about The Secret coming out in the early 2000s? Because Spiritualism was happening in the 1850s and that was building on traditions of Romanticism.

BLVR: Mesmerism, Swedenborgianism—

AYG: And that was building on mystical practices going on in the Renaissance, which was drawing from Neo-platonism, and so on back to ancient times. Magic is always here. But we might say that now, magic is anything that stands outside of what the modern mind thinks of as rational. In a sense magic defines the modern era, there’s a great book of essays about this called Magic and Modernity edited by Birgit Meyer and Peter Pels where they talk about how magic is always present, it’s always standing outside, and is always bigger than the rational. It’s more wild. It’s endless and boundless.

Witches are at home in that wild place. We’re of it. I feel like now Medusa, Hecate, those figures, are creeping out of that void and into the fissures within our culture, and finding places to grow and thrive. I don’t mean that in a bad sense at all, they’re like mycelium. The ecological function of witches in our world is one of re-enchantment, re-enchanting the world and making it sacred again. In essence, witchcraft is the religion of nature. It’s about recognizing nature as inspirited, and listening to and tending to the life force inherent in the water, and air, and earth, and the trees, and the plants, and the animals. In fact, we could say that the practice of honoring the sacred in nature is the oldest religious tradition. Animism far predates Christianity or Buddhism or Islam. So we can’t really say the practices of witchcraft are a new thing, we’re doing the same thing but in a way that makes sense in a contemporary context. Magical practice is always completely contingent on the time and place in which it is produced, contemporary witches have to adapt their practices to the reality of capitalism and global warming. It’s hard to worship in a grove of trees that’s drenched in Round Up or bisected by a freeway.

BLVR: On the topic of finding its way into the fissures of culture, could you talk about the relationship of magic in your life to your creative practice, and also activism? I know that you’ve talked about this on your podcast, and you talk about it in the book in a pretty direct way—and also you were on Fox News.

AYG: Tucker Carlson.

BLVR: Representing witches. How are all of these practices interrelated for you?

AYG: One of the things that I think is really important about witchcraft is that there is no spectator, there is no spectacle, everyone participates. In the West Coast traditions of Reclaiming, which I come from, there’s no high priestess; everyone is a priestexx. Which means that we are all responsible for what is happening. We are not the sheep guided by a prophet. We are also prophets. We are the sheep, and the grass and the mountain. We are all creating the cone of power together. And so, inherent in the theology of witchcraft is that we have a responsibility to create the world that we want to find and work interdependently.

As far as creative practices, I also feel like witchcraft demands creativity, it demands poetry, it is poetry. Creativity is an act of intimacy. But even though the imagination is fundamental to the practice of witchcraft, that doesn’t mean that it’s opposed to science or reason. Many of my clients work in science-based fields like neurology or tech. One of the women in my mother’s moon coven when I was a child was a molecular biologist, and she had a rational and scientific mind, but she also chanted to the moon goddess. That’s what I love about it, we can do both at once.

BLVR: I actually think that most metaphysical or spiritual or mystical practices refer to themselves as scientific. Actually the New Thought Movement, the one that I was raised in, came out of Christian Science, and considered itself a very rational school of thought. A lot of writing came out of the movement, and writing was central to the practice, which I feel is very much in line with your own practice. At one point in the book you talk about automatic writing, and the automatic writing of the Surrealists. You practice it and you come up with the word “Clifton,” which ends up being the last name of the person you finally find to rent you an apartment.

AYG: Yeah.

BLVR: Automatic writing is also a practice in metaphysics. You practice it as a witch, the Surrealists practiced it as a technique, we do it in metaphysics. There’s something interesting to me about that.

AYG: If we follow that line of inquiry to its logical conclusion it begs the question: if all religions consider themselves to be so rational or scientific, then can any be true? I don’t believe the world was created in seven days by some guy in the sky with a beard. I don’t believe that. It seems completely irrational to me.

BLVR: Right.

AYG: I also know that a lot of Christians don’t take it as literal.

BLVR: It’s like saying to a Catholic, “Do you believe in the saints?”

AYG: Right, what do they say?

BLVR: I think they say, “Yes, but.” Or the angels. You talk about angels in your own book, too. I think something that’s interesting about metaphysics is that it’s also a healing practice—at least Unity was also a healing religion, and in Spiritualism, for instance, they heal with their hands. It’s in line also with the idea that our thinking shapes reality, that we make reality with our minds—because our thinking leads us to act in a certain way, but also because we have inherent power.

AYG: Right. There’s a way that we see, like a language—

BLVR: Language shaping reality.

AYG: The act of creating shows you how malleable reality is. That’s why Plato says that poets should be exiled from the city, because poets have so much influence over people, and can “enflame their passions”. But to become a poet, to become a witch, is to find your way out of that exile in the underworld. In becoming a witch we can say, “I don’t have to just accept the reality I’ve been given, I can create reality too.”