I met Ashleigh Bryant Phillips a few years ago, on a reading tour we did together for the Traveling Appalachian Review. Ashleigh’s not from Appalachia, and neither am I. She lived in rural North Carolina and would take a bus up to Pittsburgh for the first reading in the series that’d then creep south into West Virginia and finish up in Asheville, NC.

I felt lucky to be driving my car dead west, getting away from NYC and off into what I considered, actual America. Most of the literary readings I ever did were in Brooklyn bars, but here was a chance to do something different. Howard Parsons organized the tour. Thanks Howard Parsons.

At a rest stop, I tweeted about the upcoming readings and spelled Ashleigh’s name wrong and got a quick reply over DM, “My name is spelled Ashleigh, not Ashley.” That was our first interaction, I hate that it was. I’m sorry again, Ashleigh. I clicked on a link to a short story in Ashleigh’s bio and read her work for the first time. I was blown away.

The first reading we did I found out the way she reads to an audience is just as captivating as her writing. She’d lugged along a guitar amplifier and while she read, a recording of the night birds in her hometown sang behind her.

We drove south in my car into West Virginia, listening to country music with the other writers, Michael Bible and Devin Kelly, all of us telling our life stories and laughing like fools. A friend of mine had moved to San Francisco and I kept telling everybody in the car funny stories about him. A few days later, the tour was over, and we all went back to our jobs and lives. The funny story friend, Joey, called me on the phone and said he’d gotten a postcard from Ashleigh. The two became pen pals and then next I heard he was on an airplane and moving into her house as a roommate, in her tiny town, Woodland, population 801.

The next time I saw Ashleigh, it was wintertime, I drove seven hours down I-95 to visit them both in Woodland. She lived in a dilapidated farm house, cold, no heat, with a little gang of feral kittens she’d rescued from a barn—we sat around drinking beer and shivering. You held the kittens and they kept you warm, you stamped your feet and popped another beer and told another story to distract yourself from the cold. What was Ashleigh working on? Her stories, of course. The ones that became Sleepovers. The captivating ones I’d heard her read on the road with the birds in the background, and new ones too. Exciting work. About the kinds of people that lived in the tiny town I was visiting her in. Their heartbreaks and joys and sorrows and what it felt like to be lonely. Next time we hung out, she came to Jersey City. I threw a party and she made venison sausage dip.

I saw Ashleigh again just before her book came out and Covid hit. Now she was vegan and it was Leap Year and we were sitting in a bar on 13th street in Greenwich Village called Spain and very drunk on martinis in the middle of the afternoon. The waiter was a man named Julio, 90-something years old. Ashleigh treated him like she treats everybody, respectfully, and as a friend, “Can we please have another round, sir?” While we waited for our drinks, I hit record and Ashleigh Bryant Phillips and me had a conversation, some of it is featured below.

—Bud Smith

ASHLEIGH BRYANT PHILLIPS: Here’s another thing—folks don’t realize how rich and full of life their lives are. They feel like in order to have a story they gotta own a couple of parrots or dye their hair a wild color or have an affair.

THE BELIEVER: Being a writer is being interested not just being interesting.

ABP: Yes. Being curious. And thoughtful. And listening. And observing. Maybe that’s the actual key. Because then you’re not creating you’re just taking what you know and rearranging.

BLVR: I don’t believe there is a thing that’s truly mundane… do you? How do you rearrange your experiences into fiction?

ABP: Nothing is mundane because you always have the power of your imagination. I just take my experiences and the stories I’ve heard and tell them through a past self or alternate self and let my imagination fill in the blanks where I have questions.

BLVR: That feels right. My parents wouldn’t tell me much about their lives because they don’t find themselves very interesting but if I text them they will answer any question. They think texts don’t matter. Is it easy for you to talk to your kin in person or on phone?

ABP: Good god, the phone. My folks make compelling stories out of any old thing. They love it. It’s part of who we are. Whenever I call them on the phone it’s always at least an hour endeavor.

BLVR: Tell everybody what Woodland is like.

ABP: It’s located in the Northeastern part of North Carolina, in one of the poorest counties in the state, the surrounding counties are also some of the poorest in the state. The whole area is dying out from poverty related problems and the people left there struggle to get by. Hurting people don’t have access to the help they need so lots of folks have alcohol and drug and obesity problems. Quality education and mental health care isn’t really accessible. People pray a lot because God’s the only one that’ll listen, you know. Crime has significantly increased and the law doesn’t really get things done. It’s like the Wild West. All my family members back home sleep with pistols and the nearest good up-to-date doctor is about two hours away. Before that the doctor in my town was still in practice at the age of ninety-two. Woodland’s a mile long on all sides. All the streets are named after trees pretty much except for Main Street and John Edwards Lane. I grew up on Hemlock. My Mama lives on Spruce now and when I moved home after my MFA I lived on Chestnut Street. Woodland has no grocery store (but it did when I was little. J.J.’s had a butcher and sold hog jowls and pig feet and livers, etc. etc.) two gas stations, and about six churches and that’s counting if the one on Main Street next to the Grapevine Cafe is still open. But the church I grew up in is outside of town in the country where all my mama’s family went.

BLVR: A very rural area.

ABP: Yeah. One side of my mama’s family was farmers but they’ve all died out or moved off to bigger places. The other side of my mama’s family still farms and I grew up out there jumping in cotton after they picked it. The town of Woodland is surrounded by fields and fields. As are all the towns in that part of North Carolina. But whereas lots of towns in Eastern North Carolina had big tobacco money, Woodland did not. At one point my town had a zipper factory and two dueling casket factories. By the time I came along there was just one casket factory left but then that stopped. And the bank closed. And the grocery store closed. When I went to college we got a Dollar General. But I think mostly what Woodland is known for nostalgically is The Shrimp Fest and The Horse Show. Me and my sister and the other little girls in town would walk out in the rink and hand ribbons to the winners of the horse show. We had to wear white with a red bandanna. But now, I’d say Woodland is mostly known for having a good trusty Sunday buffet.

BLVR: There’s not a lot of work there. And you’ve moved away partly because of it. You said you’re working three jobs now.

ABP: Since graduating college I’ve always had multiple jobs at once. Most of them have been in sales. I like meeting new people and helping them find what they need and asking them where they’re from and getting to know them.

BLVR: I’ve seen you do this pretty often, you’d just start talking to anybody, always kind and respectful, and before I knew it they’re telling you their life story. Has working as a salesperson helped your fiction? What about when you sold cotton seed and car insurance back home?

ABP: It’s a treasure getting to know random folks.You can learn so much beauty and hurt. By just getting them to open up a little. And if a sale happens in the process that’s good for the big boss up top but for me it’s about making a connection with folks.

BLVR: Selling them glasses or wine.

ABP: Yeah one of my jobs (in Baltimore) has been selling eye glasses and the other’s selling wine. And you wouldn’t believe how many folks without accents ask where I’m from, “Texas? Or Tennessee?” and then I’ll say, “Actually North Carolina.” And then they’ll often say, “Oh where in North Carolina? My niece or daughter goes to Duke or UNC.” And then I’ll say, “I’m from the Northeastern part of the state. It’s really isolated.” And then they’ll say, “Oh, so near Asheville? We just love Asheville!” And then I’ll say, “No, Asheville is in the mountains in the Southwestern part of the state.” I’ll use my hands to show the difference between the Northeast and the Southwest on an imaginary map in between us and say, “I’m from a very flat place, I never saw a mountain until I was in 4th grade.” But obviously I explain all this in a very understanding way so as not to embarrass them. People really don’t like to admit that there’s a place they really don’t know about.

BLVR: They taught me how to pronounce the word ‘Appalachia’ all weird in a New Jersey grade school. I’ve been corrected. I get it.

ABP: Funny you bring up Appalachia. Folks often think I’m Appalachian. And maybe that’s because our American consciousness likes to associate white people with Southern accents as Hillbillies and so that makes them Appalachian. And a good bit of the Appalachian Mountain range ain’t even in the South! Anyway people also probably assume I’m Appalachian because there’s been this boom of writing from the region recently, with folks like Scott McClanahan leading the way. And he’s also white like me with an accent. All it boils down to is folks have never heard of where I’m from so they want to make me from somewhere that they have heard of so it’s easier for them to understand me. I wrote a whole collection of short stories they can read to understand instead.

But back to my day jobs. I work barback and kitchen shifts at the most dreamy organic wine and sake bar I’ve ever been in called Faddensonnen, named after a Paul Celan poem. The owner, Lane Harlan, is a badass and trailblazer as far as ethical and compassionate entrepreneurship goes. During my interview there, my manager told me that organic wine started in Georgia and this tickled me to death. I said, “Oh, wow! Kinda like moonshine? With families and communities having their own recipes and methods?” And he said, “Yeah, even churches!” And my mind exploded with joy thinking about little Catholic churches in the deep reaches of Georgia making wine with whatever local grapes they have. And this idea enchanted me for a long time, this idea of old Southern winemakers deep in the cut. It wasn’t until months later that I realized it was Georgia, the country.

BLVR: I wonder if they grow peaches in Georgia, the country.And you’ve been teaching too?

ABP: I’m very grateful for this lil gig teaching fiction for the West Virginia Wesleyan College Low Res MFA. I remotely mentored two fiction students throughout the semester and read their work and held monthly conferences with them over the phone. West Virginia has a place in my heart because Breece D’J Pancake means so much to me. The first time I read about farmers on the page, spoken from their point of view was Breece. My Shakespeare professor in undergrad went to UVA with him and one day when I was in his office he handed me Breece’s collection. Breece gave me permission to write about my people.

I love this quote by Jack Kerouac. And it’s kinda funny because I haven’t read one full novel of his. But anyways, he made this list of rules for writing and one of the rules is: “No fear or shame in the dignity of your experience, language, or knowledge.” That helped me too.

BLVR: That’s amazing…

ABP: Every class I teach I go over this quote on the first day. And we break down what that means. For me it means freedom to be honest on the page without caring about what others think, how many words you know and if you know how to spell them, and where you came from, what your parents do, where you’ve been. It’s freedom to be yourself.

BLVR: What was the MFA program like you taught at?

ABP: It was a week long in-person residency in WV. That was really special. The whole MFA met together to do workshops and readings. We were in Blackwater Falls, a secluded state park. And New Years morning this pair of white tail deer came to the back of my cabin and I fed them apples and I took that as a sign that I’d be okay this year. Things with my book specifically.

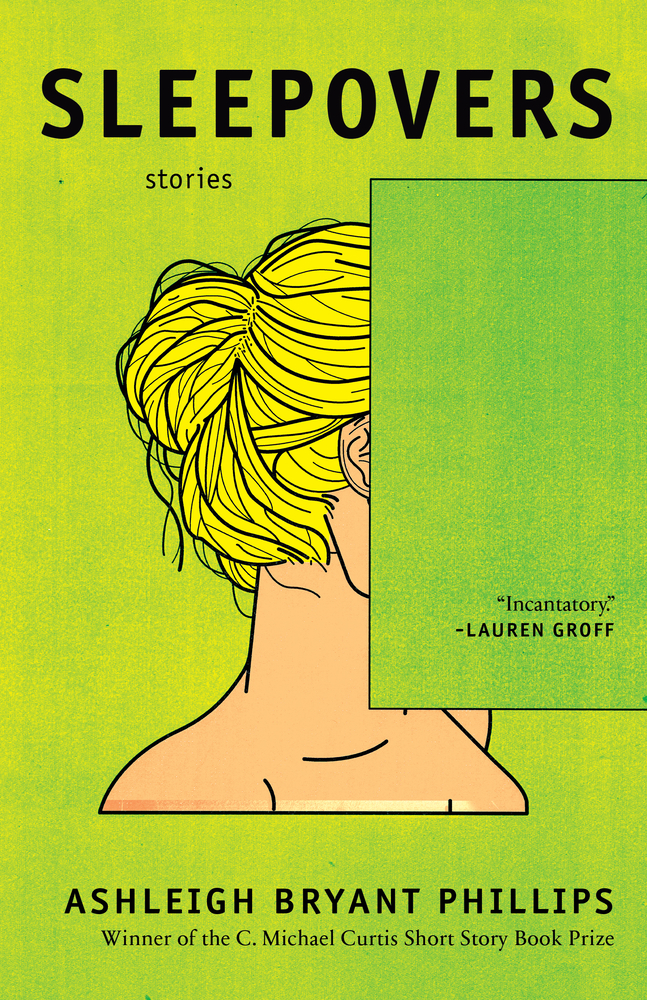

BLVR: Sleepovers won the C. Michael Curtis Short Story Book Prize. Congratulations, the deer are soothsayers.

ABP: It did and deer sure are. But bless Lauren Groff, the contest judge. And thankfully I hit all the particulars for the contest. You had to be living in a Southern state and have no other fiction books. The manuscript had to be at least 140 pages long. You’d get $10,000 and publication with Hub City Press, an indie based out of Spartanburg, South Carolina.

BLVR: Were you more comfortable sharing your manuscript with a press from The South, being from there?

ABP: I honestly didn’t think I’d have a book published anyways because I didn’t see work like mine out in today’s literary world. I didn’t live in NYC or go to Iowa. I didn’t have those automatic ins. But honestly once I found your work and the work of Scott McClanahan, my mind started turning. Here y’all were being yourselves on the page. You, a welder from Jersey who wrote on the job, and Scott, some big nerd from someplace no one had ever heard of in West Virginia. And y’all were outsiders to that top tier publishing world just like me. But through indie publishing y’all were getting out the most gripping modern fiction I could find. This coincided with a reading I was invited to do back in Wilmington where I got my MFA. John Jeremiah Sullivan was there and he’d brought Donald Antrim and Wiley Cash was there too. Well after I read, John and Donald gave me such great encouragement and talked to me like they knew I’d have a book out someday, no problem. And this floored me.

BLVR: Your confidence was low.

ABP: I’d been living back at home in an old cold house, struggling for even the local Belk department store to give me more hours. One cousin was paying my gas bill to keep me from freezing, and the other was bringing me deer sausage and corn and sweet potatoes from the field so I could eat. I’d moved home to be with my Daddy while he was passing away, which was hard enough. But I was terrified of getting trapped there after he died and I needed money to get out.

BLVR: How did your father die?

ABP: Early onset Alzheimer’s. He was in a home by the time I moved back to Woodland after my MFA and then quickly after I got there hospice was called.

BLVR: I’m sorry about your dad.

ABP: Yeah it’s the way things were fated. There’s no rhyme or reason to it. You can’t escape it though, so the best thing to do is get in there and do the best you can. It’s scary but there’s no need to be sorry. Fate didn’t give me any other way.

BLVR: “An Unspoken” from Sleepovers was recently published in Paris Review.

ABP: I found out it got accepted while I was standing in the Post Office. I got the email notification and gasped so hard that my boyfriend, Joey, thought somebody else from home had died. And then I just kept yelling over and over “Holy shit!” and Joey told me to try to keep it down and I apologized to the woman in line with us and explained that I’d just been accepted into The Paris Review and she said, “Congratulations.” I’m just really thankful—it still doesn’t really feel real.

I guess I always dreamed that if I ever got published in The Paris Review, I’d emanate sparkles going down the street like how I felt when I lost my virginity. But really the next day I had to go to work on the sales floor just like usual and nobody said anything to me about it. I was in NYC when I first saw it in print at McNally Jackson though and then I went around the corner and got this most expensive perfume I’d been pining over for about a year and then we ate the most wonderful Chinese dumplings.

BLVR: What was the perfume?

ABP: Debaser by D.S. & Durga. It smells like the greenest woods with a bright ocean salinity. I’d love for them to sponsor me.

BLVR: They should. But what about that feeling you had that you couldn’t get published because you were rural? What happened about that?

ABP: I still think I somehow slipped through the cracks. It’s all so wild. But it’s happened before, Larry Brown was from Tula and I don’t know if it’s the same down in Mississippi but where I’m from you’d have to drive a good two hours in any direction to just get a copy of The Paris Review. And even though my folks couldn’t really understand the weight of it, they were and are so proud of me. I can hear my mama telling my cousin about it right now: “That Paris magazine … Ash, what’s the name of it?.. That’s right, Bubba, Ash is getting published in The Paris Review.” And I can hear my cousin quickly in the background say, “Well, tell her I’m really proud of her.”

BLVR: Do you like living in Baltimore? Big change, right.

ABP: It’s the biggest place I’ve ever lived. When I first moved here it took a good three or four months to get used to all the car sounds and foot traffic, and I don’t even live in a super super busy spot. I still don’t know if I’m sleeping properly. I feel like a foreigner. The only strangers up here who I’ve met that know the whereabouts of where I’m from tell me they were born near the area or their grandparents or their cousins are still there, etc., etc. This one man even grew up with the same cold remedies as me, like putting onions in the bottom of your socks before you go to sleep at night. And this other man I met comes from a BBQ chain family in NC and I followed him on Instagram and he posts the most wonderful food cooking vids, I mean he posts some good eating. He told me he was gonna look my book up. Who knows if he did? But it’s always so magical meeting someone who knows the small out of the way place all your family comes from.

Another time, I went in this corner old school diner up here and every table had a bottle of Texas Pete on it. This is how every eating place is back home. But it’s really something else, how powerful seeing those Texas Pete bottles were for me.

BLVR: Just about two years now I’ve been reading your work. You did one of the best readings I’ve ever seen one night. You read your story, “Earth to Amy.”

ABP: Oh gosh, I remember that last night in Asheville when I read that story at Kris Hartum’s house. It was one of my newer ones and I only read the beginning of it (I think) because it didn’t wanna read too long. But I picked that one because it mentioned Tim McGraw and Michael Bible had been playing Tim’s greatest hits in your car as we drove through the Appalachian Mountains. That story is in the collection. And I remember you telling me afterwards that I was gonna ‘make it.’

BLVR: Well you were great.

ABP: I was so nervous that trip, I played recordings of bobwhites and exhaust from trucks before I read those first two nights to make me feel more comfortable.

BLVR: Bobwhites, yeah.That’s what those birds are called. To feel more at ‘home’?

ABP: Yes. But that last reading I didn’t play any of my comfort sounds before I read. At that point, I saw how life could be if you were just yourself and recognized for who you were and your work was heard and appreciated.

BLVR: I talked to you before about what it was like coming back from the city when your degree was over.

ABP: At that point I was living in Woodland again and had not felt ‘seen’ in what seemed like a million years. I was hired for a position originally intended for my sister selling cotton seed, car, and tractor insurance. And I knew that I’d be walking back into an environment where people didn’t understand my degree or who I was or my interests. I knew I’d be working with folks who hadn’t seen or heard a lot outside of their upbringing. And sure enough I couldn’t really talk to anybody about things I cared about. And I heard close minded, stuck minded things in the office that hurt my feelings.

BLVR: How’d you deal with it?

ABP: I tried to listen to classical music in one earbud to calm my nerves, only to have my boss tell me to lose the headphones and pressure me to come to the Bible study he led once a week. But I needed full time work so bad for the money. I cried and cried before I took the position. But with money from my paychecks there I was able to buy my greyhound tickets for that TAR trip. And GOD, it was such a blessing to be with all y’all then. Seeing everybody being themselves and reading from their work. Everything was authentic. I’mma tell you what, I sure didn’t want to take that greyhound home from Asheville.

BLVR: In your final story of Sleepovers, the narrator is superstitious. Are you? Hexes and jinxes and black clouds and all that.

ABP: My friend Anastasia is from the country like me except she’s from very, very rural Russia. One day Anastasia and me were back home riding around the fields with the windows down trying to listen to as many bird and bug and frog sounds and she paraphrased this poem for me by Fyodor Tyutchev called “Silentium.” Here’s the first and last stanza:

Speak not, lie hidden, and conceal

the way you dream, the things you feel.

Deep in your spirits let them rise

akin to stars in crystal skies

that set before the night is blurred:

delight in them and speak no word.

Live in your inner self alone

within your soul a world has grown,

the magic of veiled thoughts that might

be blinded by the outer light,

drowned in the noise of day, unheard…

take in their song and speak no word.

Yes, I do believe by keeping sacred things close to you, by never speaking them, they can never be shot down and you can never lose them. But as far as hexes and black clouds go, I unfortunately kinda believe that life is like a Thomas Hardy novel, we will be plagued according to the socioeconomic class and family we’re born into and there’s nothing we can do to change that. And even if we do rid ourselves from hexed or black cloud situations, there will always forever be the memory of it, so there’s really no escape.

BLVR: How do you approach writing a short story? Did it change over the haul of stories that made up Sleepovers?

ABP: I have this thing in me that wants to get out. So I write it down.

BLVR: You’ve done it a service letting it out of a cage?

ABP: Sometimes yes. Sometimes it makes me really sad to go back and re-read the stuff. Like I don’t want to revisit that. So the process of getting it out is sometimes scary.

BLVR: And not a therapy.

ABP: I wouldn’t say it’s therapy because even after I get it out on paper, I’m still haunted by it. I don’t have a greater sense of peace.

Yeah—the only good thing maybe is that others who read the work are like “Hey, this has happened to me.” Or “I feel this way too.” And yeah, maybe the reader can feel less alone.

BLVR: Do you feel you haven’t totally done your job if you’re not haunted by the writing after?

ABP: If it doesn’t hurt me to revisit the piece then I know that it’s not powerful. So yes. It’s not at its full potential.

BLVR: Is it not at its full potential if it can’t really hurt you in the real world?

ABP: Your emotional world isn’t the real world sometimes. But when you’re in your emotional world, it feels like the real world. So I say wherever you are on this spectrum of realization, what you’re afraid of is very important. If you’re about to read a short story out loud and you’re not a little bit afraid about re-entering those emotions then in my opinion, it’s not at its full potential. There has to be that vulnerability.

BLVR: How do you start a new story?

ABP: Before I can write the story, I have to know the whole character’s life story (to the best of my ability). Sometimes the character talks and I just transcribe. Other times, I have to decide what moment I’m going to dip in and explore and show. Is it going to be an afternoon, is it going to be a week, is it going to be a brief overview of a very few select details from a lifetime? That’s what I like to call the container, picking that container is crucial because that itty bitty moment you’re going to share from this person has to be representative of their whole life somehow.

I also have to figure out who is going to be telling the story.

My mentor Clyde Edgerton in grad school told me to read Mark Richard’s autobiography House of Prayer No. 2, which ambitiously is told entirely through second person. So I tried the second person point of view out and a new story flew out of me. It’s mostly just waiting around until you figure out the right way to get your story out of you and then it just comes out.

BLVR: Just catching them before they fly away over your shoulder.

ABP: And once it comes out and I find that months later I’m satisfied with it then it’s done. I will say this though, I didn’t start really fucking around and revising my stories until I started trying to get published. And God it’s really awful inviting this whole audience to sit at your wonderful sacred table where they were never invited in the first place but that’s how it works.

BLVR: Did you feel this way editing your collection as a whole?

ABP: Sleepovers has very light revisions/edits and I’m happy about that. I’d say it’s 90% me and that’s probably only happening because it’s coming out on a small press from Spartanburg, SC who believes in and trusts the voices of their writers. I can’t help but feel that if I was debuting somewhere much bigger then I would have had to refine and streamline these stories or make them even more connected or even make the whole thing into a novel.

BLVR: Above all else, you’re compassionate to the characters. Is that a priority?

ABP: You’ve gotta care about your characters. Compassion is everything. Otherwise you don’t learn new ways of seeing and hearing and feeling.

BLVR: Can artists be created by their own work?

ABP: All of my favorite work was created from folks who had a need to get it out and then someone called a capital-C Critic came by and said they were an artist. I’m thinking of women like Minnie Evans who just one day heard a voice from God tell her to start drawing her visions and she did. Her pure singular voice so directly sings through the images she created. And then folks came along and she was discovered and now her work is in museums all over.

BLVR: Alonso Quijano decided one day to rename himself Don Quixote and become a knight, riding off. Maybe making stories up is the same thing?

ABP: That’s beautiful! All I can say is I love being moved. It takes me out of my own world for just a little bit, where I’m so often troubled with my own shit. And being moved by art gives me rest, even if I am caught up in the harsh realities of others, for just a lil bit I am relieved of myself—I’ve transcended. And I just want to create things that do the same for others. Feels pure.