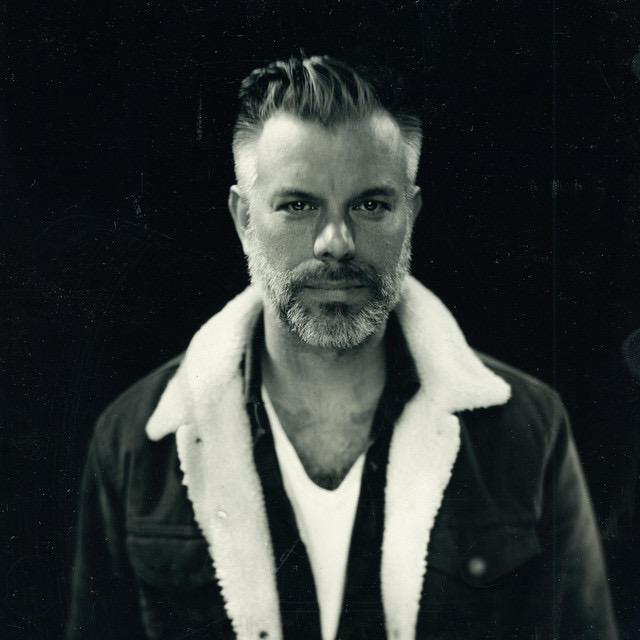

For more than twenty years, it’s Ben Nichols’ voice, a southern growl, that has defined the Memphis punk-country band Lucero, for which he is the songwriter and vocalist.

Nichols and Lucero have aged from their punk roots and songs about girls they idolize to singing about the South, the family and the ghosts that follow all of us. Their last album, 2018’s “Among the Ghosts,” brought a new found maturity and confidence that can only come with years of practice. The songs have become fuller, richer, and more deftly tuned. Their punk roots still hide in the guitars and pacing, but now, after years of exploring what it meant to be a “southern band” from a city like Memphis, Lucero rounded itself into a textured sound that feels like a culmination of exploration.

Nichols, for his part, has embraced the folklore of the South as a literary place. In 2009 he wrote a solo album based on Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian called “The Last Pale Light in the West.” He grew up in a suburb of Little Rock when, as he put it, the city was searching for its soul, downtown abandoned save the kids plugging in each night at small venues to play punk shows. His home was a traditional suburban one: his dad worked at the family piano and furniture store—for which Nichols would work at post-college, drawing pictures of the furniture for newspaper ads—and his mom stayed at home with Nichols and his two brothers.

I sat down with Nichols and Lucero guitarist Brian Venable before the first of a three nights of shows in Cambridge for a winding discussion about music. A few weeks later I got on the phone with Nichols to try to mine his personal history to hopefully understand how he found his way to becoming the voice of a band that has stayed together and evolved while someone never giving in to trends or bigger ideas—never embracing the “alt-country” popularity push or the constant evolution of punk rock ideals or given in to the growth and constant commercialization of Country music to bank on Nichols looks or voice.

—Kevin Koczwara

THE BELIEVER: You grew up in what sounds like a very suburban and simple life, without much turmoil.

BEN NICHOLS: I wish there was some kind of, you know, great storytelling tradition in our family or, you know, some kind of history with country music or something really cool to say. But my dad has been a salesman for most of his life and he’s a talker. He loves talking to folks. That’s what he did for a living basically. And loved going to movies. He took us to movies since we were real little. We were seeing stuff that we probably shouldn’t have seen at the age we were.

BLVR: What movies is he taking you to?

BN: Stuff like stuff like Wildcats with Goldie Hawn, Big Trouble in Little China. Fletch is one of the family’s favorite movies. Me and my brothers, that’s the one we remember from when we were kids. Those are the kind of movies we grew up on. I’m not sure what influence exactly those had, but I’m sure it had some kind of influence.

BLVR: What age did you get into music?

BN: At fourteen I went to my first punk rock show, which some kids put on the Women City Club in downtown Little Rock, Arkansas. It’s weird. It’s where they had cotillion classes. It was kind of an odd place for a punk rock show. But somebody rented it out. It was Trusty and some band from Texas that I don’t remember and another Little Rock band called The Numbskulls. They were my age or maybe a couple years older and it blew my mind. At thirteen, fourteen—rock stars are adults. Musicians are adults. And these were kids my age. That definitely made an impression. I realized: oh, man, I can do this right now. Then it took me years to do anything real.

When I got to be eighteen or so, going to college in a small town about thirty minutes away from Little Rock, that’s when I started my own band. Nobody would let me play. So I had to book my own show in the parking lot of my dad’s furniture store. And I booked my band and I found like four or five other bands and put us right in the middle, because it was my show. I didn’t want to play first, and I don’t want to play last. So I put us in the third slot. It worked out and then after that they’d let us play whatever shows we wanted.

BLVR: What kind of music were you listening to?

BN: Whatever I could come across. I remember for my twelfth birthday I got the Violent Femmes first album. Before that, all the cassette tapes I owned were movie soundtracks and stuff. I had the Beatles White Album for some reason—because I’d heard about the Beatles. And I was like, I should check that out. I love that album now. I don’t think I quite got it at the age of ten or whenever I bought it.

I had a random collection of 45s my dad listened to. We listened to a lot of 50s Rock and Roll. My dad loved Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis and all that stuff. He thought the Beatles ruined rock and roll because they’re all drug addicts and hippies. Anything pre-Beatles he liked. When Buddy Holly died, my dad pretty much gave up on contemporary music.

That Violent Femmes cassette tape that I got for my twelfth birthday from a friend that kind of opened the door and then you get a cassette tape from a friend that’s got Seven Seconds and the Dead Kennedys on it, you’re like, “Holy moly,” or goofy stuff like the Dead Milkmen or whatever you might see on MTV. You know, I saw the video for “Don’t Want to Know if You’re Lonely,” the Hüsker Dü song off Candy Apple Grey. I went to the record store and bought Candy Apple Grey because it had that one song on it. I didn’t know anything about Hüsker Dü, but that song off MTV was that was my introduction to Hüsker Dü, which is kind of ironic.

You’re just scraping together whatever you can with very limited resources. It’s the old days where you make cassette tapes for your friends and mixtapes and stuff. That’s how it all started. And then you start going to these shows and you’re buying seven inches from bands that come through town or you’re buying records at the record store that only exists for two months. Kind of piecing stuff together and figuring out what it is you like. I always liked the more melodic stuff. All the stuff from Memphis was very hardcore with guys growling lyrics and not much melody. And I was like, man, maybe that’s like jazz and I just don’t understand it. I like the rock and roll sound and stuff.

BLVR: For sure. Some of it has some soul, but like, it doesn’t have the same type of soul that punk has, if make sense.

BN: Fugazi is still one of my favorite bands. That’s melodic. That’s got rock and roll in it. Some of your heavier hardcore bands, it’s just noise to me, but Fugazi, that I understand and none of my bands ever sounded like Fugazi. I couldn’t make that work. I would love to. But I listen to them all the time. And they were everybody’s favorite band for a long time.

And then the rules. I didn’t smoke or drink anyway at the time, so that didn’t really apply to me. I didn’t have to worry about any of that stuff. I didn’t really start drinking until Lucero got going. So I was in my 20s already when I started drinking. Back in high school and in college, none of that— trying to get into bars or sneak into bars or, you know, have somebody buy you booze, that didn’t play into my growing up in music at all. So I had no dog in the Straight Edge race.

KK: What is the genesis of the drinking then? Is it just a stage fright because you’ve already played in bands?

BN: Stage fright is a part of it, but you’re right, I’ve been in bands before. I think it’s got to be more than that. Although, with Lucero It was, we’re talking about punk rock being reaction to the overproduced prog rock, you’re in Memphis and you got all these very noisy, sludgy kind of hardcore bands and then you got a few kind of poppy bands, but we consciously wanted to do something very quiet, very intimate and very personal. So Brian and I, that’s what we started. I guess Brian thinks that I wrote those two songs after he asked me to be in a band, but the first two Lucero songs have been around for quite a while. And I’d been thinking about doing, if not something Country-ish then something quiet. And that was kind of a reaction to all the punk rock that was going on, and maybe all the rules that you had to obey just to be a punk rock band.

BLVR: A hardcore show, everyone is something. Everybody’s got a rule.

BN: Yeah, and with Lucero, I liked the idea of having no rules. Usually the bands we were playing with, three or four other bands on a bill, none of them sounded like what we were doing. It was a little extra scary just because of that. And the songs were getting a little more personal, so you’re putting yourself out there even that much more. The audience can understand the lyrics that you’re singing because there’s nothing really loud covering them up. And it’s being that personal and at that volume can be a little intimidating.

BLVR: So where does the country sound come from? Where is that desire to play? Because you start listening to country music like what is?

BN: Yeah, I did. Back then Johnny Cash kind of came with the whole punk rock toolkit. And then I figured out Johnny Cash is actually from my home state. He’s from right here. In those years I was kind of learning more about my granddad and some family history—the cotton farms and the old family lived up in the hills then came down and bought cotton land and worked cotton and that stuff became more interesting to me. I learned about Arkansas and where the family came from and Johnny Cash obviously fit right with that and the Grand Ole Opry fit right in with that, Hank Senior and all the classic country stuff. I was intrigued with my family history and that classic Country stuff fit right in. I was listening to a lot more of that. And maybe I was like, well, I could give that a shot.

I think I might have seen something in like, the local weekly, maybe a songwriting contest or a talent contest or some kind of Country flavored contest that might have been the inspiration to write those first couple songs. I said, man, I could probably write a country song. I just kind of went down that road for a little bit. Really liked it. It was all the punk rock stuff was sounding the same to me then and I wanted to try something different. I don’t know. Who knows what’s real and what’s authentic? But it seemed a little more real and authentic to me at the time.

BLVR: It’s kind of like a mishmash of who you are.

BN: I figure so and I kind of like that about Lucero. It’s a mishmash of everything I grew up with. You got my dad’s old 45 of 50s rock and roll. You got the classic rock that I grew up listening to on the car radio every morning on the way to school. You got some punk rock stuff I discovered in junior high. And then you got that kind of discovery of roots music as I discovered more about my family history. Put all that bag and shake it up. That’s kind of what we do.

BLVR: What about your granddad?

BN: Well, both sides are pretty interesting. But the one that really caught my attention was my dad’s dad. I figured out that he’d been in Europe [during World War 2]. From about two weeks after D Day until the end of the war, I think he was in a 35th Infantry Division. It took me forever to find that out. All his records burned up in St. Louis in a fire. My dad says a bully beat him up and stole all my granddad’s medals. My dad could totally be lying about that. I’d bet, in fact I’m ninety-percent sure he is. But basically nobody in my family knew anything about him. All I could get was the service dates. There were a couple of old photographs of him, there was a pin on one of his overseas caps and I got a book that had pictures of thousands of these little pins and I figured out what the Infantry Division he was in.

Then he came home and with my grandmother they had two kids and got divorced not long after my uncle was born. [My grandfather] was pretty hard drinker. In and out of the VA. He was the only one in my family that drank and smoked. He would disappear for days and not come back to the farm for like a week, apparently driving all over the state and I don’t know what the hell he was doing. That kind of character, obviously, is intriguing. And so that was… so thinking about him and what music was he listening to when he was driving that truck? I don’t know. That’s what I was thinking about in the early days of Lucero.

KK: You’re also driving all over the place.

BN: That was it. It was romantic to me. That’s what I wanted to do. And yeah, in the old days I didn’t drink so I could stay up all night and drive all through the swamps or the hills of Arkansas. I did that a lot. I don’t know if I was specifically trying to emulate my grandfather, but I love driving around the back roads at night and ending up in out of the way places. That’s kind of the beginning of Lucero. And then I started drinking myself, not just because of the stage fright. It definitely was probably influenced a little bit by my fascination with my grandfather and my fascination with all the old school country guys. I don’t know how to do this job. I kind of have to maybe imagine myself in somebody else’s shoes. I just try to pretend like I’m someone a little cooler than I actually am. Once whiskey got involved with Lucero shows, it was there for good and It was hard to shift gears back into being sober.

BLVR: Yeah, it’s part of what we think and expect. Especially at the show people are giving your shots.

BN: That’s pretty much every night. Now, in the old days it turned out bad. Now, it usually is fine. The last few songs will get a little sloppy, but we make it every now and again. You still have a train wreck of the show, but then it’s usually my fault. Or it’s something’s wrong. You never know. But usually we do okay nowadays, but in the old days, we had train wrecks.

BLVR: And so I have to ask why did you write the Cormac McCarthy album? Why Blood Meridian?

BN: Number one reason is because he had so many good lines in there and I wanted to steal them. I was reading it for the second time and I was like, ‘holy shit, that would be great’ that’d be great; that’d be great.’ I just started underlining stuff and I was also getting ready to go on the Revival Tour with Chuck Regan [Hot Water Music] and Tim Berry [Avail]. I’d be playing solo acoustic and I was like, “maybe it’s time to write [new songs].” I can kind of make this separate project from Lucero. It’s easy, you know if I don’t have to decide if the song is gonna be Lucero song or a solo song. It’s about “Blood Meridian” and is part of the solo project. So it was easy to distinguish from Lucero. “Blood Meridian” has such a great quality to it. It’s a Western, so obviously, that works with what I kind of naturally go for. You can kind of think about it as if it were a soundtrack to a film and the book itself is cinematic.

BLVR: It’s almost perfect writing.

BN: Exactly. So it was a real natural kind of decision to make it. There was not a lot of forethought in it. I think I wrote the Chamber’s song first. Maybe just thinking that would be it. But once I wrote that, there’s more; there’s more I can steal.

BLVR: What was the reception like?

BN: I don’t know, the songs didn’t get played a whole lot. I played some of them on the Revival Tour, but that wasn’t the venue necessarily. Greg and Tim Berry were playing acoustic guitars, but they were basically playing punk rock songs on acoustic guitars. And so playing something in a six-eight beat with just two strings at a time and fifteen year old kids in that crowd did not give a shit about what lines of “Blood Meridian” I really loved.

I don’t think there was much response to that record. A few people that read the book, I think responded positively. I know a few years later, Lucero was playing in San Antonio and a lady came up to me and give me her card and said she worked for the Cormac McCarthy archives at the University of Texas library, San Antonio library, and wanted a copy of the album for the archives. Maybe that’s the real deal. Maybe not. I don’t know. I like to think that it’s in the archives at the Cormac McCarthy library. I’m not gonna research it any further. I’m just gonna assume that it is. Better than a subpoena or a court order to stop singing the songs.