“Pretending to be living people is fun but perilous, pretending to be imaginary people is fun and far less risky.”

Two Faces Danny Hellman Did Not Like Drawing:

Kevin Costner’s, circa Waterworld (1995)

William Shatner’s, circa TJ Hooker (1982)

At some point in the late nineties, a series of letters began arriving at the NYPress, the alternative weekly where I was working as a staff writer. It took five or six weeks, after dutifully running the letters in the mail section, for the paper’s editors to notice each of the letters seemed to have been written off the same template. Each was written by a woman of different ethnic origin, who had been deeply offended by an innocuous story in the previous issue, using that as an excuse to launch a vicious assault on the paper as a whole. Read them individually, and they seemed utterly sincere. Read them all together, and it was obvious they were a prank. When the editors finally recognized this, and furthermore learned who was penning the weekly angry missives, the last of the series ran under the headline “Good Career Move.”

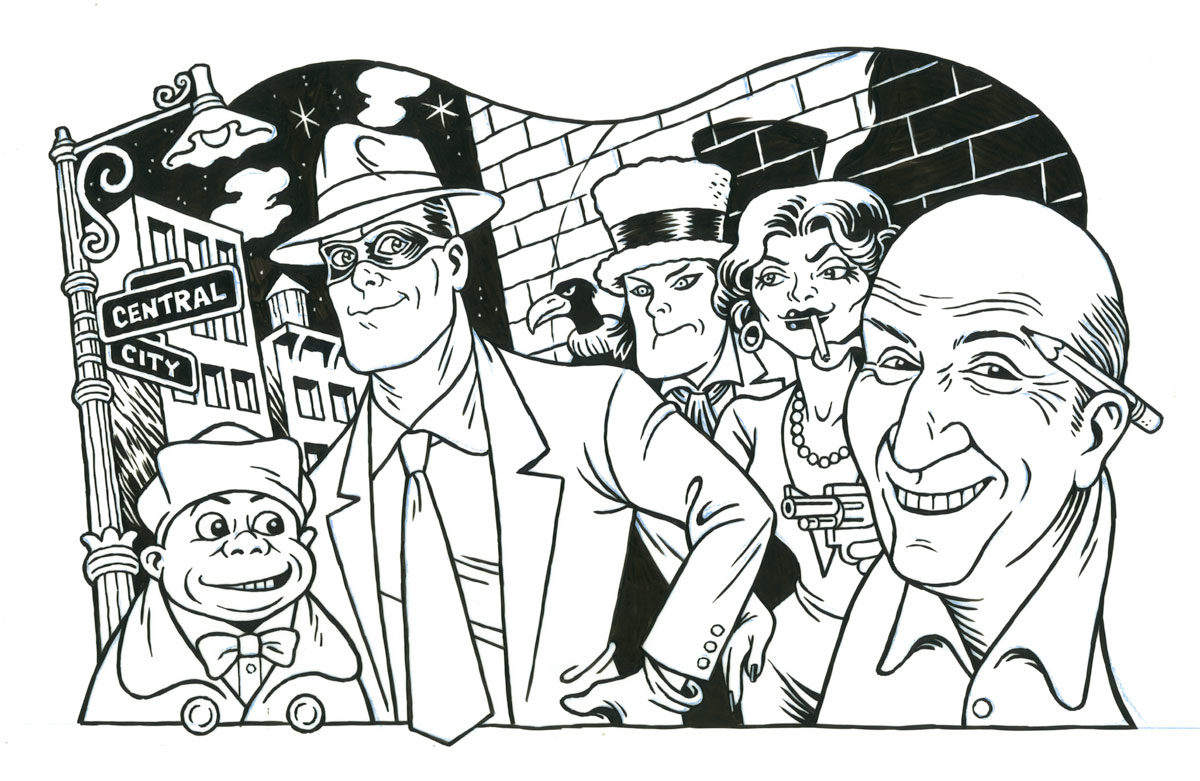

I first met Danny Hellman at the Press a few years earlier. Hellman was one of the paper’s foremost illustrators, at a time when the Press boasted a staggering array of notable artists from the world of indie comics, including Tony Millionaire, Kaz, Sam Henderson, Michael Kupperman, Russel Christian, and Ben Katchor. They all had unique styles, all were blessed with their own brilliance, but Hellman’s illustrations were unmistakable, marked by clean lines, perfect detail, and a seemingly natural facility for sharp caricature. Apart from the commercial illustration work, he was also a cartoonist, drawing occasional strips for SCREW magazine, contributing toThe Big Book Of… anthology series, putting out his own mini comic, Peaceful Atom and the Mystery Mice, and even doing an issue of Aquaman for DC. Unfettered by the constraints of editorial illustration, when his imagination was given free reign, Hellman’s work could get pretty fucking twisted.

I hadn’t seen Danny in over a decade, and being blind can’t see him now, but to my mind he will always be a slightly paunchy fellow, bespectacled and bald save for an emoticon of facial hair. He’s a smart and funny guy, an odd mix of the comfortable and intense, both self-possessed and low-key. He seemed to know everybody and, I would later learn, was an inveterate prankster. Those letters to the NYPress were just a hint of the trouble to come.

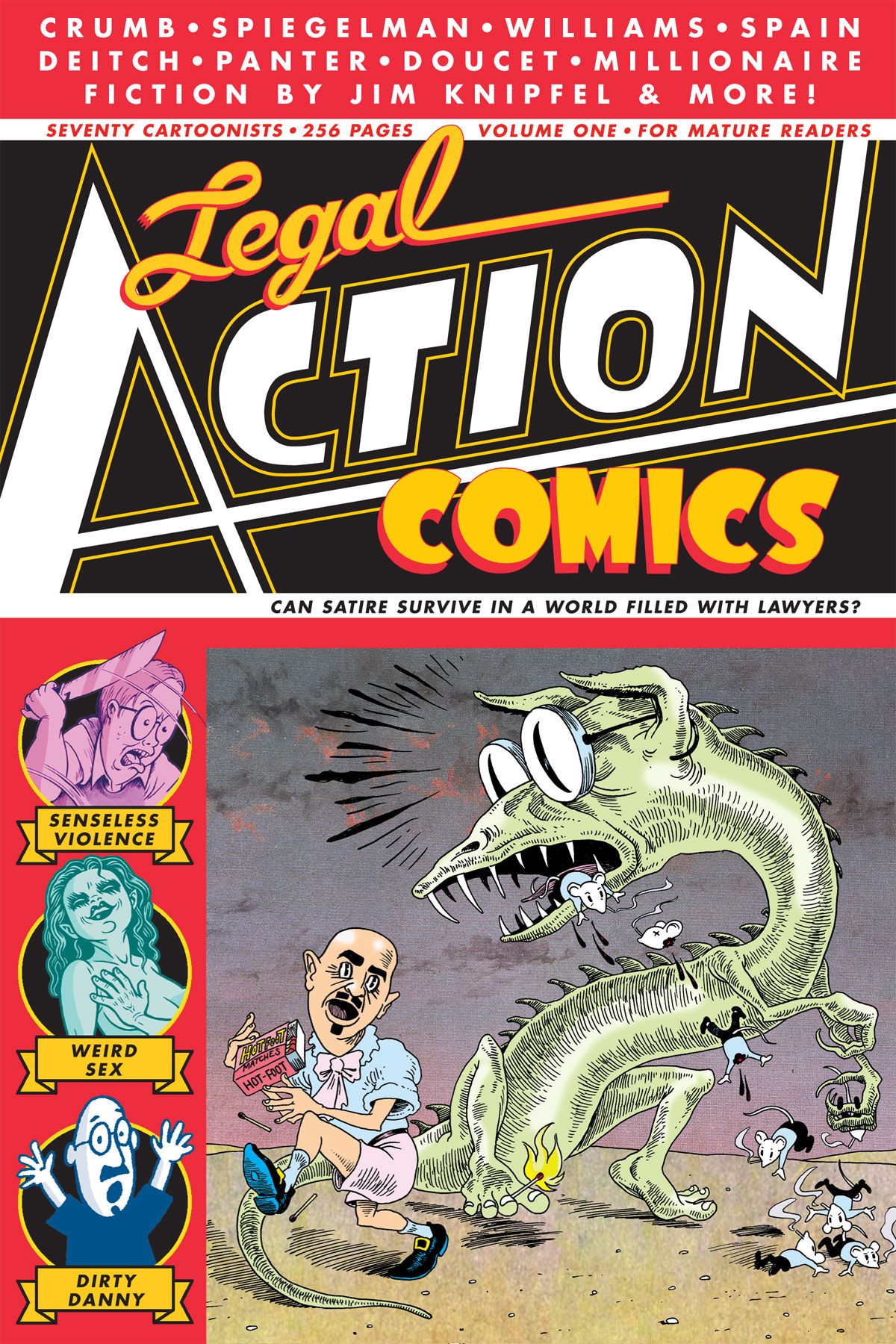

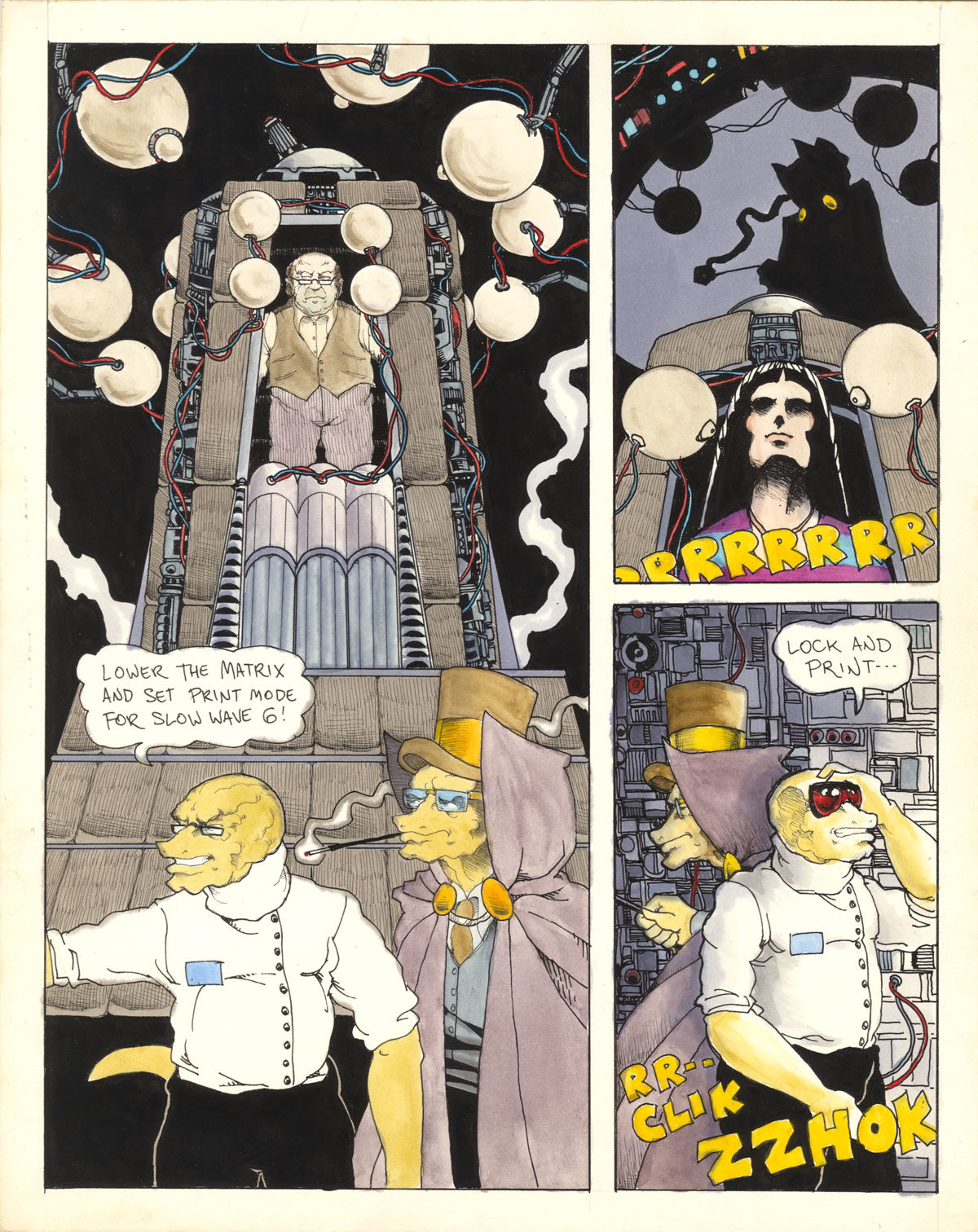

In 1999, Village Voice cartoonist Ted Rall wrote a Voice cover story attacking respected Maus cartoonist Art Spiegelman. In response to the story Hellman, pretending to be Rall, sent out self-aggrandizing emails under the subject line “Ted Rall’s Balls” to thirty-five people in the comics industry, including one of Rall’s former editors. Rall was not amused by the prank, and sued Hellman for libel, seeking $1.5 million in damages. Of course asking an American freelance comics artist to pay $1.5 million is a bit like asking a ferret to paint your living room, but that’s neither here nor there. The lawsuit dragged on for several years, until Rall’s attorney died in 2005. The case received a good deal of press at the time, but nothing was ever resolved. In the meantime, however, Hellman used the hullabaloo to edit two volumes of the benefit anthology series, Legal Action Comics. The two volumes (which came out in 2001 and 2003) were sold as fundraisers to help bolster Hellman’s legal defense fund, and featured the work of, among others, Spiegelman, R. Crumb, Robt. Williams, and Mike Diana.

Hellman was born in Germany, raised in Forest Hills, Queens, and has spent most of his life in New York. Along with the now-defunct NYPress, his work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Time, Entertainment Weekly, Sports Illustrated, Fortune, MAD and countless other respectable outlets, as well as Hustler, Genesis, and SCREW, where he was also a regular contributor from 1988 until the paper’s demise in 2006. It was his work at that latter batch that led cartoonist Sam Henderson to dub him Dirty Danny, a nickname which has stuck.

In 1995, Hellman met Linda Payson at the NYPress offices, where Payson was an administrative assistant. They later married, and today live in Park Slope, Brooklyn, with their daughter, Alice. In recent years Hellman has turned to photography, though with a very specific focus. But we’ll get back to that.

—Jim Knipfel

THE BELIEVER: Like so many other kids, you started drawing early. Unlike so many other kids, you kept at it. What sorts of things were you drawing in those early days? Were you one of those kids who drew dirty comics in the back of your notebook in junior high and passed them around?

DANNY HELLMAN: I drew comics from about the age of ten on, but these weren’t dirty comics. They were wholesome adventure stories, little more than rehashed Star Trek and Marvel Comics plots, (which were themselves rehashed mid-century pulp sci-fi literature) starring a cast of talking dinosaurs. It would be another fifteen years before I’d be dragged by necessity into the profession of drawing dirty comics.

BLVR: When did it strike you that drawing was something you could do for a living?

DH: I was an avid comic book reader as a kid, and got even deeper into comic books as I got to be ten or eleven years old, (1975 or so). This is when I started to notice the names of the artists who were drawing my favorite comics, names like Jack Kirby, Jim Steranko, Wally Wood, Gene Colan, Gray Morrow, and lots of others. Coincidentally at that time, comic collecting and comics conventions were beginning to go mainstream, which meant that fans could now easily track down back issues of comics with work by their favorite artists, rather than having to depend on newsstands for a comics fix. It was not unlike being a film fan who soaks up classic films at revival houses, rather than relying solely on Hollywood’s shitty new releases at the multiplex. I suppose this is when it first occurred to me that people were getting paid to draw all this material I obsessed over. I was attracted by the art, and had yet to hear a peep about the heartbreak, the sanity-snapping deadlines, and self-destruction that many of my art heroes went through.

BLVR: So in pursuit of that, you went to the High School of Art and Design, then spent a few years studying figure drawing at the Art Students League. And somewhere in there you spent a few weeks at SVA before dropping out. What happened there?

DH: A bunch of factors combined to send me running for the exit after a month or two at SVA. Foremost among them was my dad telling me that I’d need to get a job to keep my tuition paid. The way I saw it, if I was going to suffer the indignity of getting a job, I’d be spending that money on weed and records, not tuition. Another pivotal moment was when a lame-ass painting teacher assigned my class to buy buckets of latex wall paint and start slapping it around on canvas without giving a thought to technique or preparation. Then there was the nude male model in a life drawing class who angled his ass to face my friend and I, and then grabbed his ankles. Finally, the fact that SVA felt like a note-for-note reprise of my high school experience, (down to a nearly-identical cast) but at a vastly-higher cost was enough to push me, already school-averse, to get the hell out of there.

Only after dropping out of SVA did I start to devote serious time to life drawing, (at the Art Students League, the Project for Living Artists, and one or two other NYC spots). There was something about the combination of low cost, zero instruction and nude women that appealed to me, and I’d say it was during those few years of concentrated life drawing in my very early twenties, (1984-1987 or so) that I acquired any useful drawing skills.

BLVR: Although your work is immediately recognizable—I mean, you see one of your illustrations, you know who did it—if I had to point to one artist you remind me of, it would be Will Eisner. There’s just something in the lines and characters. Correct me if I’m misremembering here, but did you tell me once you worked with Eisner? As an apprentice or doing some penciling for him or some such. Or did I just dream that?

DH: I’m a huge Will Eisner fan, he remains one of my all-time comics faves, but sadly, I never met Eisner. The fact that he taught at SVA was one of the reasons I enrolled, and the fact that Eisner went on a teaching hiatus as soon as I handed over the first semester’s tuition played a role in my dropping out. I’ve since spoken to a few former students of Eisner’s, and the consensus seems to be that he wasn’t a compelling teacher, (I’ve heard better things about Art Spiegelman’s and Harvey Kurtzman’s instruction).

The closest I came to the physical presence of Eisner was at a comic convention in Bethesda in 2000. Eisner was slowly making his way through the crowd in the dealers’ room, and huge fan that I am, I was sorely tempted to say “hi.” However, I was wearing a clown costume, and this was years before cosplay would become the respectable lifestyle choice it is today. My hunch was that approaching Eisner as a rather grubby-looking clown wasn’t the best way to meet the guy, and indeed, as he passed nearby, I got a strong sense that Eisner wasn’t the sort who’s eager to shake hands with a strange clown.

A couple of years after that, I saw Eisner onstage at Cooper Union in conversation with Spiegelman and Jules Feiffer. Spiegelman was of course sharp and witty, Feiffer struck me as a pompous blowhard, and Eisner had all the pizzaz of an elderly relative after enjoying a heavy lunch at a Boca Raton retirement community. I think he died a year or two later.

BLVR: Wait, let me back up a second. Did you go around dressed like a clown a lot in those days?

DH: I’d never considered taking on clown form before cartoonist Ted Rall socked me with a $1.5 million libel suit in August of 1999. In the early weeks of the lawsuit, I was struggling to come to grips with the reality of my situation. Linda [Payson] and I were walking up Sixth Avenue past a menswear store, and it struck me that I’d need to buy a suit for court appearances. Naturally, my next thought was, “maybe I should show up in a clown suit,” and thanks to my unhinged state of mind at the time, the clown idea started to gain traction in my head.

While I wasn’t dumb enough to actually go before a judge in clown paint, it seemed a fine idea to appear in clown form at various public events, (the comic convention in Bethesda, one of the NYPress parties at the Puck Building, and one or two other times). To my lawyers’ disappointment, I supplied a photo of myself in clown gear to the Village Voice for what turned out to be a rather hostile piece about the Rall v. Hellman lawsuit. I also wore clown drag to a benefit Soul Coughing show at Bowery Ballroom which the fine folks at NYPress organized for me, (on that night, I was accompanied by a pair of clown “bodyguards”).

My thinking at the time was that the clown gimmick might help bring attention to my legal plight, and looking back after two decades, I can only wonder, “What was I thinking?”

What I remember about the experience of walking around in a clown suit is that it elicits fairly strong reactions in strangers. I remember one random fellow throwing punches in my direction, and another random gal clutching my greasepaint-coated face to her bosom. After taking just a few steps in those oversized shoes, I’ve come to appreciate the bravery it takes to live the clown life, and thank all clowns for their service.

BLVR: Now that you mention it, I do remember you in full clown garb at one of those Press parties. I don’t think it fazed me, just given the nature of those parties.

When we were at the Press, I remember you coming into the office every week to do a spot illustration. You stood at a production table in the back and used a technique I’ve never seen before. Instead of using a standard pen to draw directly on the paper, you had some kind of film you laid down over the paper and used a stylus, as I recall. As someone who’s still confused by the concept of “paint,” could you describe to me what you were doing?

DH: What you remember seeing me do at that NYPress production table was scratching dots off Zip-A-Tone with an X-Acto knife. This technique apparently makes an impression on those outside the graphic arts trade, since it prompted Linda to sidle up to me one day and ask what I was doing.

The process by which NYPress illustrations came to be went like this: on a Friday, I’d get a call from either art director Michael Gentile, editor John Strausbaugh or publisher Russ Smith, (if it was an illo assignment for Alexander Cockburn’s column, I’d hear from Strausbaugh, if it was an illo for Russ’ MUGGER column, I’d hear from Russ, and all other assignments came via Gentile). We’d hash out a concept for the illo, (the column itself being either partially or entirely unwritten at that stage) and I’d do a drawing over the weekend.

Keep in mind, my drawings are black and white line art which, when printed, usually benefit from the addition of some grey tones. Zip-A-Tone, (a clear plastic film printed with halftone dots) was a great way to add tonality to line art, but once you apply Zip-A-Tone to an original drawing, removing it becomes nearly impossible, so I would typically get some kind of print made of my drawing and apply Zip-A-Tone to that.

So, come production day, (usually Monday or Tuesday, depending on which year we’re talking about) I’d take my drawing to Bestype, a Chinatown photostat shop at which NYPress had an account. I’d ask them to shoot a photostat of my drawing and bill it to NYPress’ tab, about which they’d invariably grumble. I’d then make a pit stop at either Dean & Deluca or the incomparable Ceci Cela for coffee and pastry, and walk the remaining two or three blocks to the NYPress office at the Puck Bldg. Once ensconced at the production table, I’d apply Zip-A-Tone to the photostat and, using a chisel-shaped #16 X-Acto blade, selectively scrape off some of the dots to add highlight effects. This was one of many secret techniques passed on to me by the mystic graphic arts masters of old and, like all such techniques, is lost in the present era’s digital deluge like tears in rain.

BLVR: So is that the technique you still use today?

DH: No, I don’t use that technique today. The malevolent Adobe reigns supreme in my world, as it has since the mid-90s.

BLVR: I remember going back to the production room once when you were working on an illo for a review of Waterworld, and you were incredibly frustrated in a way I’d never seen before. It was all in reaction to trying to draw Kevin Costner, which you described at the time as “like trying to draw a piece of paper.” Have any other figures given you similar trouble?

DH: I find people are surprised to hear me say I’m not a natural caricaturist. Drawing likenesses is something I’ve always found hard, and still do. I’d spent my early years as an artist avoiding caricature, but then came the summer of 1988, when I started working regularly for Kevin Hein at SCREW Magazine, and caricature assignments became unavoidable.

Creative people talk about the necessity of a safe space to fail, the classic example being young comedians working out their material in marginal, low-stakes nightclubs in front of disinterested audiences. As scrappy alt weeklies full of ads for sex, SCREW and NYPress were exactly the safe spaces I needed to develop my skills while meeting weekly deadlines. If I turned in a likeness that wasn’t so accurate, I could always defend myself by saying, “What do you expect for $35?”

My experience of caricature is that the younger, prettier, and blander the subject’s features are, the harder I find it to capture their likeness. To put it another way, drawing Lyndon Johnson is easy, drawing Natalie Portman is hard. I remember having a tough time with that Waterworld illo for NYPress, but my most nightmarish caricature challenges came from Entertainment Weekly, where I was asked to draw very bland, very pretty celebrities. I remember having a terrible time drawing Denzel Washington, but the worst of those EW assignments was when I was asked to draw Kathie Lee Gifford standing in Times Square, surrounded by enormous Jumbotron screens displaying her face; in other words, a half dozen Kathie Lee likenesses in a single drawing. I remember working on it in the middle of a snowstorm, ready to rip my eyeballs out, continually presenting the work-in-progress to Linda and my mother, (who lived nearby at the time) to ask if I’d gotten Kathie Lee’s eyes, nose, or lips right.

Another, more recent caricature nightmare was an assignment for Atlanta Magazine in 2012, where I was asked to draw William Shatner at three stages of his career. This should’ve been a dream job, since I’m a hopeless fan of the original Star Trek series. Capturing Old Shatner’s likeness was a breeze, and the yellow shirt and phaser do much of the heavy lifting needed to sell a Captain Kirk likeness, but I found Shatner in his TJ Hooker incarnation nearly impossible to nail down. I kept ending up with something that looked like Joe Pesci in “My Cousin Vinnie.” This was one of the rare occasions where frustration drove me to trace a photo with a light-box, an ignoble technique which, (contrary to what one would assume) does not usually yield a satisfying result.

BLVR: Not to be all nostalgic here, but back when we were in the Puck Building, the Press had a really wonderful, freewheeling, drunken anarchic atmosphere, with no real sharp lines—at least from my perspective—dividing the editorial, art, production and advertising departments. It was a lively place. You were also doing a lot of work for SCREW at the same time. What was the atmosphere like over there?

DH: As anarchic as the atmosphere at NYPress might have seemed, the scene at SCREW Magazine was more so. While not the nudist orgy that outsiders might imagine, SCREW’s offices felt like a continuous East Village house party that somehow managed to put out a weekly smut tabloid.

For most of its nearly forty year existence, SCREW occupied two floors at 116 West 14th Street. The lower floor was where the legendary leased access cable show Midnight Blue was produced, where sex workers lined up to pay for the sex ads that were SCREW’s life blood, and where publisher Al Goldstein kept his personal office. Close proximity to the tyrannical Goldstein made life for the staffers on that floor stressful, while staffers who worked in production and editorial on the upper floor lived a more relaxed existence, (except when Goldstein visited for weekly editorial meetings, which always seemed to put them in a panic). The walls of the editorial offices were covered with graffiti left by well-known underground cartoonists, the furniture was junkyard-ready, the air smelled of weed and hot wax, and WFMU was always playing on a boom box. I loved hanging out there.

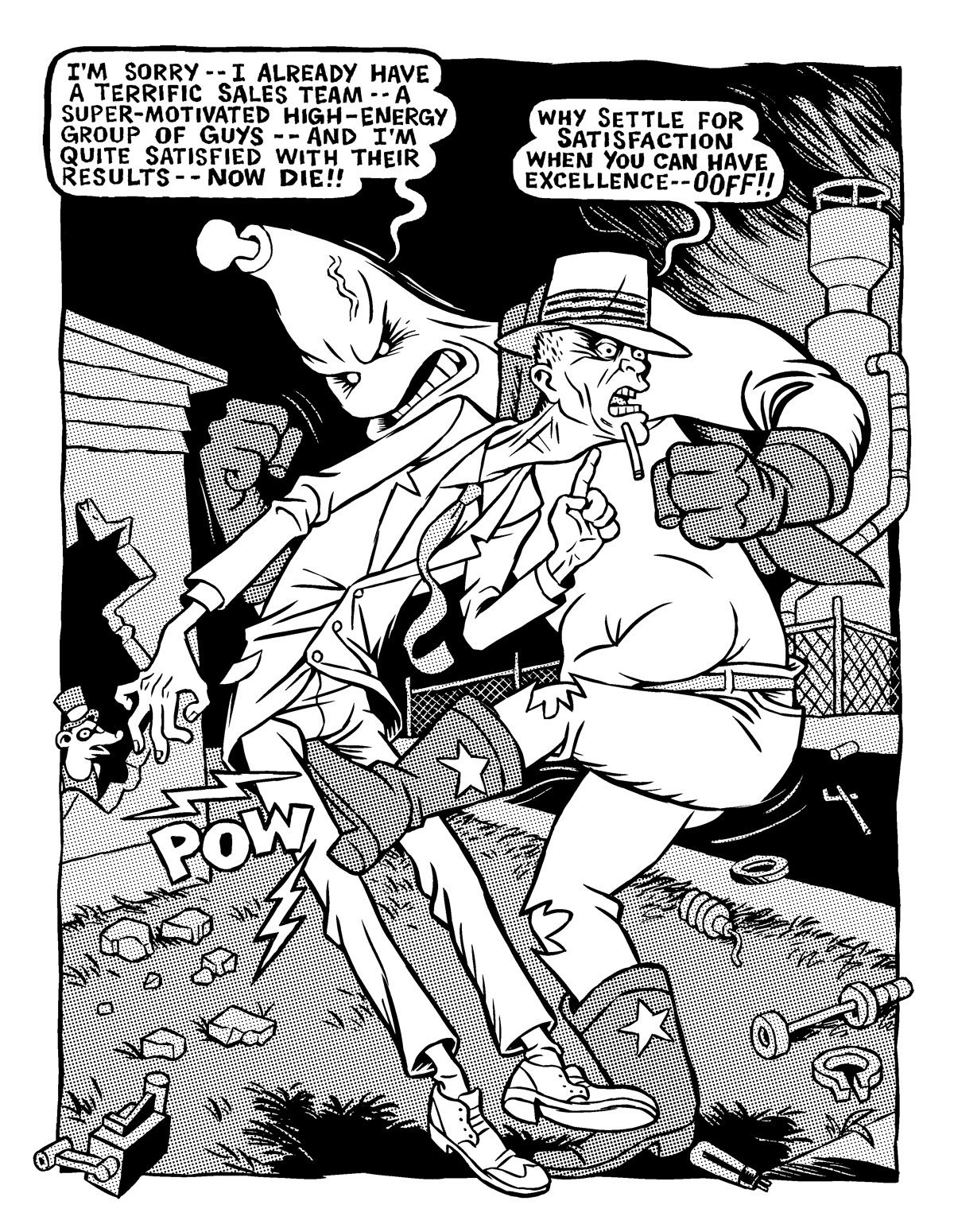

BLVR: I make the point in the intro that when you got away from the constraints of commercial illo work and were free to let your imagination go where it wanted, things could get pretty fucking strange. What can you tell me about where Peaceful Atom & theMystery Mice came from? I still have an issue of that around here somewhere, and it wasn’t like anything else you—or anyone else for that matter—had ever done before.

DH: Peaceful Atom & the Mystery Mice is a self-published comic book I did in 1995. Like many of my self-generated, “artsy” comic strips, it defies understanding. I suppose it’s my take on superhero comics, in that it pits an obnoxious quasi-superhero character named Peaceful Atom against a relentless traveling salesman character, the super-powered alter ego of a disgusting little character named Drippy Wippy, (the idea behind Drippy Wippy is that he’s just like Walter Lantz’ beloved penguin character Chilly Willy, except not a bird). Bearing witness to the battle are the Mystery Mice, a trio of drug-crazed, foul-mouthed cartoon mice.

If the strip is about anything, I suppose it’s about me reassessing my early twenties, zany years when the pursuit of getting high landed me in a number of strange scenarios I was grateful to have survived. The strip opens with the Mystery Mice loitering in an abandoned mid-century home with Peaceful Atom, (an awful bomb-shaped figure inspired by the Atom Age industrial films I was dosing myself with at the time). Peaceful Atom barks out demands for sexual favors from the mice, who are willing to oblige because the atom-powered creep keeps them supplied with drugs.

Drippy Wippy’s Shazam-like transformation into the salesman character was suggested to me by a piece of sales literature that belonged to my Dad, (a salesman and sales consultant). The pamphlet broke the word “salesman” down into an acronym whose letters spelled out, “S for Self-Starter…A for Aggressive…L for Learns Easily, etc.” I immediately made the Shazam connection, and I was off to the races.

BLVR: Speaking of side projects, and going back to the Ted Rall business for a second, you’re of course still known today for Legal Action Comics, both volumes of which had such an amazing array of artists. It must have been incredibly gratifying to have the likes of Crumb and Robt. Williams sign on. I mean, these were the gods of underground comics. Were they all folks you knew and were friends with, or did they just want to show their support? Or maybe they all just hated Ted Rall.

DH: Once the Rall v. Hellman lawsuit got underway, various folks suggested that I publish a benefit comics anthology to raise money for my legal defense. At first, this struck me as a terrible idea, since it was common knowledge that self-published comics anthologies rarely break even, let alone make a profit. It was only after watching my savings get rapidly munched by lawyers that I decided it might not be a bad idea to sink my last few thousand dollars into a benefit book before that, too, got pissed away.

Having organized yearly cartoon art shows at the Lower East Side bar Max Fish for a decade, I’d come to know just about everybody in the NYC alt comics scene, but I didn’t know any of the underground era legends I’d need to bring some star power to the book. Luckily for me, my friends Leslie Sternbergh and Adam Alexander, (a lovable, eccentric pair of East Village weed dealers who’ve since left the planet, sadly) knew EVERYONE in comics. They were instrumental in putting me in contact with R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Robt Williams, Spain Rodriguez, and a few other underground comix legends.

Spiegelman was very generous with his time, most likely because he’d been the target of Ted Rall’s Village Voice hit piece, (which had inspired me to prank Rall in the first place). Williams and Spain were immediately sympathetic to my plight, and it was around this time that I spent an unforgettable afternoon with Spain, listening while he shared tales of other cartoonists’ pranks as he drove me around San Francisco in his vintage auto. Apart from an envelope containing photocopies of two unpublished drawings that arrived in my mailbox one day, I had no contact with Crumb, and can only guess at what he thought about Rall v. Hellman.

I don’t think any of the contributors to the Legal Action books were motivated by long-standing dislike for Ted Rall. My feeling is that, like myself, most of them had been unaware of Rall’s existence until he wrote the Village Voice piece attacking Spiegelman. It’s likely that, like me, they only learned to loathe the guy after first watching him savage Spiegelman in print, and then follow that offense with a $1.5 million nuisance lawsuit over a fellow cartoonist’s joke email.

BLVR: What was intended to be the third issue of Legal Action Comics morphed into a different anthology, Typhon, which you released in 2008. Difference here was instead of big names you were dealing with a lot of young up and comers people like me had never heard of. Also, this one was in color. To date you only released the one issue—do you intend to put out more?

DH: I learned from doing the two Legal Action books in 2000 and 2003 that I love editing comics anthologies. I love rounding up talented folks and inviting them to do what they do best. I also learned that I’m terrible at publishing. I’m not a natural businessman, and alternative comics distribution is an environment that’s every bit as friendly as a bucket of hot barf is to the human face. Worse still, the further we get from the ‘60s, the less-receptive the comics readership seems to be to the kinds of zany, freeform anthologies that sold well in the undergrounds’ heyday.

After publishing the first two volumes of Legal Action Comics, I’d intended to do a third, but two events changed that plan. First, in 2005 or so, Ted Rall’s lawyer died of brain cancer, which brought the roughly five year lawsuit to a stop before it ever reached trial. Then, in 2006, our daughter Alice was born, and it would be at least another year before I could think about anything other than changing diapers and keeping a baby alive. By the time my thoughts returned to comics publishing, the idea of doing a third Legal Action seemed a dumb one, and I chose instead to do an artsier, more ambitious book. The result was 2008’s Typhon, a larger-format, full color book of which I’m still very proud, and of which I still have many, many copies resting in our basement.

Following Typhon in 2017 was Resurrection Perverts: Hunter’s Point, the first installment in what I hope will be a multi-part graphic novel series. I’m working on the second installment at about the same speed at which stalactites form, while many boxes of the first book remain with quiet dignity, (like Typhon) in our basement.

Asking if I’ll publish another comics anthology is like asking a deranged serial killer if they’ll strike again. Sanity would preclude it, so of course I’m thinking strongly about starting another doomed group project.

BLVR: So, one last question about the Rall ugliness. Did that whole experience lead you to swear off pranks, or are you still at it?

DH: The August 1999 “Rall’s Balls” email prank was the last in a batch of email impersonation pranks that very much depended on the relative newness of the internet to function. Prior to the Rall prank, I’d created fake email accounts for the purposes of pranking Maakies creator Tony Millionaire, and other cartoonist pals. The only real difference between these pranks and the Rall’s Balls prank is that I’d never met Rall, and was utterly unprepared for the possibility that he was a litigious fuck.

For me, the costly lesson of Rall’s Balls is that libel laws exist, and that we risk legal peril if we pretend to be other people, regardless of whether our impersonations are intended as jokes, and regardless of whether they cause any actual harm.

I also learned that, while pretending to be living people is fun but perilous, pretending to be imaginary people is fun and far less risky. As social media has evolved to dominate our digital lives, my prankster inclinations have naturally migrated into that realm.

BLVR: This may or may not fit in with the idea of social media pranks, as it’s something you’re doing under your own name. I took a glance at your Twitter account. In an amongst selling prints and the like, you’re also very politically outspoken in a way that effectively twists the nips of people whose nips are in dire need of twisting. Are you intentionally setting out to aggravate people, or is that merely a happy side effect?

DH: Back at NYPress in the 90s, I drew dozens of virulently anti-Clinton illos for Russ Smith’s MUGGER column. I was in my early thirties at the time, pretty much a knee-jerk liberal who accepted as gospel that Democrats are always the good guys, while the GOP are the Great Satan. Understandably, I felt a bit of a traitor drawing Bill Clinton grinning sheepishly as he stood over a kneeling Monica Lewinski, or Bubba brusquely hitching his pants up after raping a distraught Juanita Broddrick, (mind you, I didn’t feel conflicted enough to turn the assignments down).

Now in 2020, my political thinking’s somewhat more nuanced, and I look back on those anti-Clinton illos with satisfaction, along with the realization that Russ was right about those crooks.

The political thoughts you see me expressing on social media are for the most part 100% heartfelt. The 2016 election was a real “through the looking glass” moment for me. I’ve never been a fan of Trump, and doubt that I’d ever vote for him, but I’d learned enough about the Clintons to see them and the party they’ve hijacked as a bigger problem for progressives than the GOP. My vocal opposition to Hillary Clinton in 2016 lost me friends, and I have no doubt my vocal opposition to whichever corrupt, compromised candidate the DNC nominates later this year will cost me additional friends.

BLVR: Now, in more recent years you’ve taken to photography. Have you always been interested in photography, or is this a new development? Pun intended only long after the fact.

DH: I’ve always taken pictures, mostly with the intention of using them for drawing reference. Only in the past decade or so have I started taking pictures for their own sake. I’ve never attended a photography class, know next to nothing about the rudiments of photography, and consider myself a fumbling amateur. If I can be said to have any talent as a photographer, this surely stems from my experience as a commercial artist, and the strong sense of visual composition that comes with it.

BLVR: Specifically, you’ve been concentrating exclusively on cemetery photographs. You’ve taken photos in cemeteries all over the world, it seems. What was the inspiration for that?

DH: I’ve always been attracted to cemeteries. As a teen, I’d walk past Brooklyn’s gorgeous Greenwood Cemetery during pilgrimages to the White Castle on Fort Hamilton Parkway, and peer through the fence at moonlit monuments.

I’d visited cemeteries for family funerals as a youngster, but I don’t think I set foot in a cemetery as a tourist until Linda and I began traveling to Europe. During our early trips in the late 90s, I’d pay brief visits to notable cemeteries in Prague, Paris and Brussels. As the years have passed, the cemetery visits have gradually gotten longer, with me spending a full day, (sometimes two) snapping hundreds of pictures.

A smarter person than I could explain the links between Eros and Thanatos. All I can say is I’m deeply hooked on morbid eroticism, and there’s no better fix than the monumental cemeteries of Italy, in places like Milan, Genoa and Rome, (where masterpieces of 19th Century sculpture by Giulio Monteverde and others sit quietly collecting dust).

BLVR: Do you use your phone, or a standard old fashioned single reflex camera?

DH: When I’m snapping pics in a cemetery, I use both a DSLR and my iPhone. The pics I shoot with the iPhone are just highlights, shots I’ll post to social media in the evening from our hotel. Needless to say, the DSLR pictures are higher quality, I shoot them in far greater numbers, and those are the pictures I tend to edit more heavily.

BLVR: You also manipulate the photos before you post them, toying around with the colors and other such things. What all are you up to there?

DH: I use Aurora HDR and Photoshop to adjust my photos. Originally, I was only looking to correct for bad lighting, but especially with the Aurora software, I’ve had a lot of fun messing with the colors. The results tend to be painterly photos with garish, unnatural colors, and if that’s your thing, then I’m your guy.

BLVR: Do you think photography will ever supersede illustration as your primary focus, or will you always be a comics man?

DH: I’m pretty unfocused these days. From where I sit, the profession of editorial illustration, (in decline since the collapse of the first Dotcom bubble in the late 90s) appears to be entering a terminal phase. As pay rates shrink, and as publications lose whatever shred of relevance they’d once had, the thrill of drawing and redrawing the same illo of Uncle Sam holding a sack of money becomes ever more elusive.

And while I’d like to focus all my efforts on comics, my experience in comics leads me to put great store in the famous quote, “cartooning will destroy you; it will break your heart,” (attributed to both Jack Kirby and Charles Schulz). Presently, photography is something I do just for fun. It’s relaxing, it’s creative, fresh air and mild exercise are involved, and it’s a wonderful way to avoid doing the much harder work of drawing. If some lunatic started paying me to do photography professionally, my guess is I’d quickly learn to hate photography, too.