“Sometimes progress looks like little lines of explosion.”

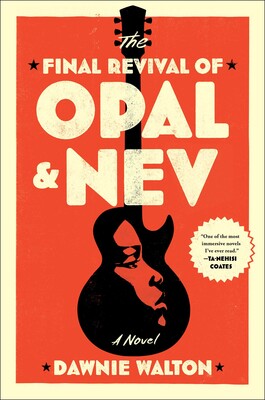

You don’t forget when you fall in love. Centering on a rarity in literature—a Black woman rock-and-roll legend—Dawnie Walton’s debut novel The Final Revival of Opal and Nev, published in March, had a lot of people saying “you complete me.” In the New York Times, Alexandra Jacobs writes, “This novel is so good, I want to rent a velvet-swagged amphitheater and gather a large audience to blare through a microphone just how much I like it.”

Walton makes you think hard about Black women artists and the people who befriend them. Like Toni Morrison’s Sula, The Final Revival of Opal and Nev choruses the sometimes uneasy, sometimes taut, sometimes sometimey friendships that involve Black women artists in search of an art form (or trying to blossom within forms that haven’t been formalized yet). In the early Seventies, Opal Jewel is part-meme, part-fashion plate, full-time public microphone, and rock-and-roll singer trying to figure out her sound. Walton satirizes the music industry, pop culture, and all the ways people can get messy.

Opal’s work defines the 1970s, and, crucially, the people around her. Walton’s background, as a music journalist, an editor at Essence and Entertainment Weekly, and a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, infuses the novel with authenticity. If novels collide and harmonize voices, then Opal’s friendships and multiracial entourage explodes the sounds of multiple communities and suggests Black women artists are both insiders and outsiders. It’s a novel that helps us understand how our era’s music and protests echoes and reinterprets ideas from the 1960s and 1970s; it’s a novel about Black women artists affecting and transforming music, culture, and community. Of course you’ll love it.

—Rochelle Spencer

THE BELIEVER: This book is hilarious.Your material is complex, so I don’t know if people talk enough about how funny this book is. It’s excellent satire because you know music and you know culture and you’re aware of how pop culture reflects views about race and gender.

DAWNIE WALTON: When I was writing, I was trying to make myself laugh. The tone I wanted to strike is how we experience real life. We experience moments that feel ridiculous and moments that feel very heavy and sometimes the ridiculousness can hide a real threat…Trump was elected and presented in the media as ridiculous but he was actually a real threat. That space is something I wanted to get at in the book.

BLVR: You connect the past with what’s happening today. You know a lot.

DW: I thought a lot about the concept of progress followed by regress, especially for Black Americans. I started this book in 2013 when Obama was president, and we thought we’d entered a watershed moment. Writing it actually took a lot. History is a bit cyclical. We’re witness to things happening that are truly terrifying. On Jan. 6, we saw the confederate flag. We saw the Voting Rights Act gutted. When Trump was elected, I called my mother in tears, and her response was, “This is how we felt when Reagan was elected.” The moment, for me, felt very terrifying. Our parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, have been witness to so much white supremacy. There’s still a lot of work to be done. What’s seen as progress is a little warped.

BLVR: You view progress as ongoing?

DW: I want to show that progress sometimes requires more focus, more attention, more urgency, then it goes quiet. We had the movements of the 1960s and 1970s; the 1980s were quieter…Sometimes progress looks like little lines of explosion.

BLVR: You satirize prominent figures and remind us how race and gender affect the way we navigate the world. Your novel is about how music is more than sound; It’s culture and protest and a document of our time…The book felt real.

DW: I love satire. I think more things are satirical than get credit for it.The book covers racism and sexism, and it reflects life with little tweaks. It satirizes media and culture and the ways different personalities are presented through public consumption. Writers sometimes avoid critiquing current popular culture (or even addressing it at all) because they want to create work that feels timeless. But I’m interested in how we connect in these different moments. People said they felt the book. Some people thought the characters were real and they had to go to Wikipedia and make sure they were made up.

BLVR: Your book reveals the trajectory of a career: Opal’s career begins in the Black Power era and the novel follows up with her in the 2010s. What made you decide to explore this generation?

DW: I’ve always been fascinated by youth culture of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when my parents were in their late teens and twenties. There was so much going on both politically and artistically in the United States: skepticism and protest surrounding the Vietnam War; disillusion about the gains and tactics of the Civil Rights Movement, paired with a beautiful increase in Black pride and resistance; and, if you look at the music charts, a stunning diversity of emerging styles and genres. You had conscious soul music, funk, the Laurel Canyon folk scene, protopunk, experimental and electric jazz, heavy metal, prog rock, Southern rock. And I found that the volatility of the era was especially interesting as I wrote the second half of the novel, with the backdrop of the 2016 election unfolding and really lighting my mind on fire.

BLVR: Was it challenging to enter this space and place ideas from 2021 in conversation with a different generation?

DW: It was challenging to enter this space in the sense that I felt a responsibility to take special care with the details of the time. Making the story feel as authentic and rich as possible was my way of respecting my elders and the complex dimensions of their experiences.

BLVR: Are we seeing enough intergenerational dialogue in fiction?

DW: I find this a difficult question to answer, because fiction is broad and vast and I’m only able to take in a sliver of what’s out there! But I will say that I always appreciate reading books that explore different generations, especially one’s taboos and rules bumping up against the other’s desire to break free from them. I can think of many novels and collections I’ve read and loved that take on such themes, particularly in exploring the mother-daughter relationship: The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw, Amy and Isabelle by Elizabeth Strout, The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan, The Women of Brewster Place by Gloria Naylor, Red at the Bone by Jacqueline Woodson. Too many to name on my shelves.

BLVR: How does someone get to be Opal Jewel? People named Opal are usually smart, but how does Opal learn to shoot #blackgirlmagic from her fingertips? When she goes into rock and roll, there aren’t a lot of role models for what she’s trying to do.

DW: At times in the book, Opal definitely comes across as larger than life — almost like a superhero, with an origin story and a very constructed image. And she is often strong and confident and self-possessed. She gets a kernel of those characteristics from her mother, and they blossom within her. But in the second half, I was concerned with peeling back Opal’s layers, what she called “her armor,” and showing her full reality. Which is that absolutely nobody is magic all the time, and there’s strength and beauty in the vulnerabilities too.

BLVR: The novel is an oral history compiled by the character Sunny Shelton, a journalist, who’d recorded a multitude of interviews with the subjects. The experimental structure of your work emphasizes each character’s personality.

DW: Writers should experiment—when you write, you have to have fun. That’s the only thing that will keep you obsessed so that you will work on it for years. It felt like play. A lot of people say, “It must have been hard because it’s so structured.” But I found that within the lines of that structure, I could do pretty much anything I wanted.

As a journalist, I read a lot of oral histories and transcripts. It was hugely fun and challenging. I want the reader to open to any page and understand who’s talking without reading the nametag. Nev speaks in run-on sentences. We recognize the elegance of Virgil’s language. I distinguished the voices by thinking about how each character would curse. It was a challenge. The Sunny voice combines everything together.

I appreciate fiction that uses different forms and styles of writing: the epistolary story “Belles Lettres,” in Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s Heads of Colored People, Candice Carty-Williams’ Queenie for the way it incorporates text messages.

I wanted to examine two outwardly opposite people and how they might have fared. Opal and Nev have something in common but they also feel a little different. They’re both hugely talented and ambitious. One of them has limited ambition, the other doesn’t, and that drives them apart. Opal and Nev never would have started off on equal footing. Opal starts off as a featured singer and then the group has this headline-grabbing moment. Out of that moment, Opal becomes more of a name and a presence. That’s why Sunny begins to squint hard and question that.

BLVR: In Opal Jewel, your AfroPunk warrior goddess, and Nev Charles, the free-spirited British oddball, you’re exploring the communal aspects of music, and the culture and communities behind it. Is this book more needed post-pandemic, after we’ve been through so much isolation?

DW: One of the most beautiful comments I receive from readers—at a time when we can’t gather and experience live music—is that they feel that they’re experiencing music with strangers. I love that this book is fulfilling that. The literary community has really embraced me. My writer friends online have been hugely supportive of this book in this time of isolation; it has been wonderful. I’ve been eager to commune with other writers. Deesha Philyaw and I have become friends through this publishing process, and we’ve supported each other’s work. I’ve also been impressed and inspired by all kinds of Black content creators. I don’t know them at all, but I really enjoy @Ryan_Ken_Acts on Twitter. They create sharply satirical videos.

I think family and community, especially between Black people, is a major theme in this work. Wherever Opal goes, she brings people with her; Virgil, her best friend, moves with her. Opal wonders how to best use her microphone, her platform, to support community. She feels that responsibility. That’s deep within Opal. That’s deep within a lot of Black artists.

I want other writers to be in the rooms I happen to be in. That’s always been a part of me. There’s something wonderful and special about being Black: you might refer to someone as a play cousin or a sister, and you see yourself as part of a family, part of a community. Someone supported you, and you want to support someone else. And it’s not a burden; it’s family. All we got is us.

BLVR: Your writing creates bridges across communities and generations. Is it too optimistic to think of fiction as connecting across generational or cultural divides?

DW: What’s really wild to me, and hilarious too, is that me and my girlfriends are deep in our forties, and some of us now have kids the same age we were when we first became friends. We laugh a lot about how different they are from us, but we’re also deeply interested in their culture. We’ve had lively conversations about books we’ve read by Black women much younger than us—Raven Leilani’s Luster, for instance. There’s some degree of voyeurism in our reading, haha, but also deep care and genuine curiosity, a desire to understand those characters and what they’re going through—and thus maybe reveal something about those coming after us in real life, or even something newly clarified about ourselves.