“I don’t think about my teacup, I just use it.”

Writing:

Is a way to be somebody, instead of nobody

Helps start the woodstove (when written on paper)

Can drive Derek Davis nuts

Published shortly before his eightieth birthday, Derek Davis’ latest novel, Evolution Unfolding in a Small Town in Western Pennsylvania, is a sprawling, rollicking, phantasmagoric, microcosmic epic concerning how the long-time residents of the rural community of Deffenburg, PA attempt to confront, among other things, a group of black militants, anti-nuke protesters, anti-Hare Krishna cultists, the United States Army, trolls, a newly-transplanted tribe of Mbuti pygmies, wildly and mysteriously fluctuating radiation levels, and the Amish. On the surface, it’s a portrait of a village which has unwittingly come to encompass the entire world, but a world turned on its head. At its heart, though never stated outright save for the title, it really is a book about human and planetary evolution. The novel’s myriad interconnected storylines are deftly held together by Davis’ singular prose, simple but sparkling as it effortlessly glides from folksy rural vernacular and scientific debate, to unexpected internal monologues and slapstick, to the mystical.

Davis’ first published novel, Gifts of a Dead Man (2011), which he describes as “Midwestern magical realism,” is an occasionally Surrealist noir-ish mystery about the efforts to uncover the identity of a stranger who drops dead in the parking lot of a roadside diner in southern Missouri. His second, No Bike (2017), is a violent and nihilistic biker revenge novel, though that leaves it sounding much more genre-specific than it actually is. And in Back Alleys (2018), he gathers together several decades worth of kaleidoscopic short stories which run the spectrum from science fiction and fantasy to farce. But lurking behind them all was Evolution, the novel he’s been working on for some forty years now, and it shows. Like Joyce or Pynchon or Gaddis, beneath the raucous humor he has packed a lifetime’s worth of experience, the endless vagaries of the human condition with all its messy foibles, into the novel’s five-hundred pages.

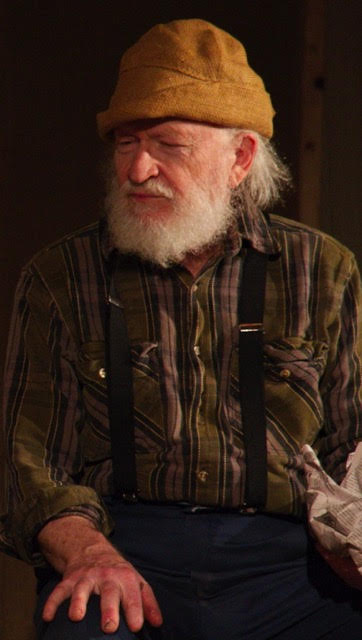

Davis was born in NYC in 1939, but would spend most of the next sixty years in Philadelphia, most of those on baring St. in the funky West Philly countercultural enclave of Powelton village. From the early Eighties through the mid-Nineties, he was on staff at Philly’s first alternative weekly, The Welcomat, initially as entertainment editor, then as editor-in-chief. Under his guidance, the paper was irreverent, funny, iconoclastic, a little sloppy, and always unpredictable, a bit like the man himself. After leaving The Welcomat (now called Philadelphia Weekly) in 1994, and long before the general public was even aware of the World Wide Web, he launched the website Sam Johnson’s Revenge. Imbued with the same spirit he’d brought to The Welcomat, the site (which only lasted about a year and a half) is still considered by many perhaps the Internet’s very first general interest magazine. In 1999, Davis and his wife, artist and actress Linda White, bought a small vacation house in Dushore, a rural community tucked away in the mountains of upstate Pennsylvania. A year later they moved up there permanently, where along with writing, chopping firewood and chasing bears off his porch, Davis has been a driving force in the local arts council.

A little over thirty years ago, Davis published my very first story, back when I had no intention of becoming a writer. After asking me to write a weekly column for The Welcomat, he would remain my editor for the next seven years. When I first spoke with him by phone in the summer of 1987, from his voice I was convinced I was talking to some hip youngster with an expensive haircut and an Armani jacket. When we met not long afterward, I was confronted instead with a Tolkein character: a small, bearded man with a fringe of gray-blond hair and a mighty beak of a nose that separates two quiet and thoughtful eyes. He has a great bark of a laugh and tends to avoid ties, jackets, and shoes whenever possible. He’s both homespun and urbane, bawdy and intellectual. His musical tastes run from Medieval compositions to Balinese Monkey Chants to Steve Reich to Killdozer, and his bookshelves swing from Dickens to the Gnostics to neuroscience to horror and sci-fi pulps from the fifties. He has one of those rare and agile minds that remains forever curious about most everything, and all that he’s gathered is reflected in a fiction that is more uniquely brilliant than he would ever likely admit. He’s a rare and true American literary eccentric.

—Jim Knipfel

THE BELIEVER: When did you start writing?

DEREK DAVIS: What’s weird is that in my teens, when I didn’t feel like anybody most of the time, I was trying to become the next Robert Benchley. I read as much of his stuff as I could get my hands on, plus Stephen Leacock, who was Benchley’s main inspiration. My mother—she wrote minstrel shows—encouraged this, even typed my stuff up for me on the electric typewriter down at Christ Church, where she was the secretary. I didn’t relate to mom as a person, but when it came to humor we were somehow on a perfect level. Then at Penn I wrote a daily column in my senior year at The Daily Pennsylvanian. Again, mostly humor but not entirely.

I guess writing was a way of being somebody instead of nobody, but outside of the writing itself, I was still nobody. I never spoke up in class at Penn, made no friends outside the paper. I lived up there in this old building with the most comfortable couch in the world. I don’t think I ever consciously and maybe even unconsciously wrestled with any perception of myself in the world. It was just there, the perception, like my teacup is there. I don’t think about my teacup, I just use it.

BLVR: Was that column for The Daily Pennsylvanian the first thing you ever published? That would have been, what, the late fifties?

DD: I published one humor piece in the high school paper, which was monthly I think and, of course, controlled by the priest who ran it. He added a dumb two-word line—“‘Nuff said”—that pissed me off so I never sent in another piece. My mother kept harping on somebody she knew who had a daily column at Penn in the late forties, so it became, I guess, a godlike goal that I thought wouldn’t happen but led me to join the paper as soon as I got there in 1957. I wrote play reviews and other odd stuff the first three years. I was a shoe-in for features editor my senior year, 1960-’61, so gave myself the column, called “Etc.”

BLVR: You spent most of your life in Philadelphia, yet So much of your fiction, long before you left Philly, was set in small rural towns. What was the attraction?

DD: That goes back to growing up in Havertown, a Philly western suburb then known as South Ardmore, semi- or more-than-semi rural. I loved Cobbs Creek, three blocks down, and picking blackberries along the way in an undeveloped block. After we moved to the city, I spent years lamenting the loss of Hastings Ave., and our quarter-acre yard with its weeping willow and apple and cherry trees. Our summer vacations were almost always to the mountains, along the Skyline Drive and Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia and North Carolina. I never liked Philly, hated the noise, the traffic (and its legendary lousy drivers). I thought I’d never get to live in a place I could love again. Damn, did I luck out.

BLVR: When it comes to the novels, as off-kilter as they can get, how much do you draw from personal experience, and how much is pure imagination?

DD: Well, Gifts of a Dead Man is based on a real stretch of Business I-44 in Western Missouri that we’d drive through to get to Linda’s family in Kansas. Marilyn’s Café was the Wagon Wheel along there, pretty exactly as described, though I think we ate there only a couple times. Dynamite simple food, and Grace, Marilyn’s waitress, is based on a specific encounter there, still the most memorable waitress I’ve ever run across.

The rest of the characters were out of my head, as I often am. No Bike is sheer imagination—I’ve never even ridden a motorcycle, but had it checked out by a guy who teaches bike courses. Some of the Back Alleys stories come out of places Linda and I had been to, like Chaco Canyon. As for Evolution, I have no idea where these characters rose from, but once Deffenburg came into being, I lived there for about a year. Loved everyone there, the good, the bad, the ugly and the unscrupulous. I wanted a microcosm of the whole wide world. I don’t think I got enough religion in because I don’t really understand religion, but the rest felt fully real.

BLVR: When you finally did move to Dushore, did it take time to adjust after a lifetime of Philly, or did it feel like you finally came home?

DD: It was home before we even moved in. The second or third time we’d vacationed here, before the full move, I started crying when we got halfway back to Philly because I was leaving home. I didn’t have a true home after Hastings Ave.—Baring St., the house itself, was home, but not the city and the goddam fucking car alarms going off every fifteen minutes. If I could have been sure somebody was actually trying to steal a car I would have run out to help them.

BLVR: Do you think the move affected your writing at all?

DD: I’ve written more up here than ever before, but much of it was the dozen plays for the arts council and the Roving Theater.

BLVR: Did you see those arts council plays as an extension of your own work, or was it more like work-for-hire?

DD: Definitely not work-for-hire, all volunteer, no one got paid. I wrote a couple short plays in Philly, fun but not good. Up here, the arts council held Renaissance feasts and I did a short play for the first one, Elizabethan court, kind of flat until Linda showed me how to make it stage-worthy. My playwriting came directly out of Linda’s experience in the theater. God is she sharp. The next year we put together a commedia dell’arte that worked beautifully, would love to take it on the road. The Roving Theater came out of a multi-county attempt to put an historical show together that never happened, but our group decided on a cycle of eight plays about specific small communities, each held in that community. I wanted real plays, not pageants, with local historical figures in character-driven scenes, interleaved with modern local scenes. I think the best one was Treeline Fever, about lumbering at the turn of the 20th century contrasted with the modern fracking scene—much humor and a guy proposing to his love in a restaurant. Rule of thumb was, every play had to have a drunk scene and a murder scene. Others wrote scenes which I’d weave together with my own. The scripts are on the arts council website.

And I forgot to mention collaborating with [his daughter, artist and filmmaker Cait Davis] on a screenplay. All the basic ideas are hers and we kicked that back and forth over fifty times. She hopes to direct it some day. Again, like with Linda, she taught me how to put a new form of writing together.

BLVR: I know that Evolution had been in the works for some time, but were any of the other novels written in Dushore?

DD: Dead Man was entirely new. No Bike was a manuscript still wrapped in cellophane from 1979 or ‘80; somebody found it in the desk drawer of a woman I’d left it with because she said she’d show it to William Styron. Obviously she didn’t do a fucking thing with it. So cleaning out stuff a few years back, I unwrapped it to use for starting the woodstove, began reading and realized it was a hell of a lot better than I’d remembered.

I retyped the whole thing into Word and made far fewer changes than I would have imagined. My granddaughter Abi did a fine copyedit on it. And Evolution, of course, I thought I’d never finish, much less publish, but I started the last once-a-decade edit and really bored into getting all the details right. Now I’m working on a novel that’s driving me nuts.

BLVR: And how does Dushore compare with the fictional towns you’ve created?

DD: The people here—the ones I know well—are mellower and friendlier than any town I’d imagine. Sometimes they’re just so nice and accepting that they seem more fictional than the people and places I’ve manufactured. But the oldster natives, and boy do we have oldsters, almost all claim it used to be almost tribal, with the different ethnic and religious groups separated into tiny communities separated by mountain roads and dueling with Trumpian vitriol. Sounds like Porky Pine in Pogo: “Don’t like anybody.”

Sometimes they’re just so nice and accepting that they seem more fictional than the people and places I’ve manufactured. But the oldster natives, and boy do we have oldsters, almost all claim it used to be almost tribal, with the different ethnic and religious groups separated into tiny communities separated by mountain roads and dueling with Trumpian vitriol. Sounds like Porky Pine in Pogo: “Don’t like anybody.”

BLVR: Back to what you were saying about Deffenburg and the characters in Evolution for a second. All of your books have been driven by a cast of characters, usually of the oddball variety, but still very real. Sometimes these personalities can overwhelm the plot, and I mean that in a good way. You’ll likely deny this, but in your books and stories you reveal, despite your self-perception, a deep understanding of human nature and behavior. Even the tribe of pygmies here are not in the least cartoonish, but perhaps more human than a lot of the other characters. Or most real people.

DD: I don’t know if I really understand human nature, but not feeling human in a full sense I must have spent a hell of a lot of time observing, trying to figure out how it all worked, being alive in the world. Something soaked in, I guess. The characters do take over for me and I’m always glad when they do, but sometimes it makes it very difficult to stick to a coherent plot. Which may be why it takes me so long to write. When you look back at what sticks in literature and what falls away, I think that’s the major divide. The potboilers hit it big at the time, when they come out, but what lasts is the examinations of human character—well, except for the Lovecraft nuts who live for scenery chewing and gelatinous adjectives.

I set up a cast of characters, and then they tend to run off and do their own thing. As for the pygmies, that’s a bit different. The whole pygmy culture [in the book] comes from Colin Turnbull’s book The Forest People. I don’t think any anthropologist has ever given more love to the people he documented, brought them as alive as your next door neighbor. He understood them at a deep level. Malinowski, by contrast, hated the Melanesians he studied, so can you trust what he had to say?

But Njonke grew out of the ground, I don’t know another way to say it. He wasn’t in Turnbull and he isn’t likely to be found in any tribe, a little too good to be true. [A friend] thought he was too “noble savage” when she read an early draft. There’s a lot about him that’s not noble at all, petty. As an example, when he says with the cards, “The game plays me,” there it was on the page and I wondered, “Can that be true, is he right?” and I had to think about it for quite awhile before I decided, “Yeah, he is.”

BLVR: Now, Evolution is set in 1979. Was that when you started working on it?

DD: Started in 1980 as I remember it. It’s a little unnerving to see that both No Bike and Evolution happen in 1979, a little too frozen in time when they come out thirty-plus years later.

BLVR: Well, having read both recently, I can say the year isn’t really an issue. They’re just as relevant and timely today. They haven’t aged at all. So, do you recall what your initial inspiration for Evolution was? That was not long after Three Mile Island.

DD: I used Three Mile Island, a very handy touchstone for the scientific aspect, but the impetus was that I thought I’d only write one novel, it was all I had in me, so it had to include everything. And everything naturally leads to evolution, the cosmos, all that inflated inner crap. I needed to bring it all together in one place, so Deffenburg, with the radiation somehow echoing the planetary evolution. Looking back on the charts I drew back then, I don’t understand some of it at all, what they represent.

BLVR: How did the novel, well, evolve over the next four decades?

DD: I’d hit at it about every ten years, shuffle events, both because they seemed out of “proper” order and because they violated my changing ideas of how evolution works or what I’d learned about, say, geology. This last major shuffle, about three or four years ago, I carefully ran the plot alongside the latest that’s known about Earth’s planetary evolution, which meant more shuffling events or a physical change in emphasis. Something that I hope doesn’t stand out is that the weather throughout—wet vs. dry, hot vs. cold—echoes what’s known of Earth back to the beginning. Of course the problem comes when, fifty years later, somebody proves that’s all crap. But for now, I like that aspect. Oh, and when I changed the plot order, I’d have to go back and change things like moon phases. Other oddities that shouldn’t be obvious—all transitions are meant to cover exactly two or three weeks, to the minute.

BLVR: In the end, does it resemble the book you wanted it to be when you started?

DD: Something like it, but hard to say. I started with pure plot and outline, but as you say the characters took over and led it along. What I started with was a general idea, rather than a real overview.

DD: Something like it, but hard to say. I started with pure plot and outline, but as you say the characters took over and led it along. What I started with was a general idea, rather than a real overview.

BLVR: Robert’s internal monologue toward the end of the novel is amazing. In fact all the internal monologues which crop up throughout the book are amazing—they come as close as anything to capturing the reality of the human thought process. Robert’s in particular reminded me of the last words of Dutch Schultz, had Dutch Schultz been a scientist instead of a gangster. You also recognize the almost obsessive repetition that seems to always be a part of verbal thought. Did you find those tough to pull off, or did it come naturally?

DD: Robert’s just happened. He didn’t go blind until about the third run-through, third decade turnover, because I realized he had let himself be blind in his confusion, his belief that something was terribly wrong with the science, which was sacred, while not realizing what he was doing to Gloria. How was he going to get out of hysterical blindness? Internally. That whole monologue just poured out of him, didn’t change much or think about it. By contrast, they other internal rumblings were hard as hell, mostly in the sense of how to present them on the page. I used multiple colons, multiple spaces, all sorts of mechanisms that looked like shit to break the thoughts down, then finally came up with the staggered ital text that seemed to work. Glad you like them. When I look back on them, I’m not at all sure they read or sound like thought—but then I don’t know how others think. My mind never shuts up unless I’m pleasantly drunk.

BLVR: Going back to your Welcomat days a moment. There was something either about your style or tone that had people believing whatever you wrote, even when it was patently satirical. I remember a first person column in which you described your experiences living under a bridge for a year. And then there was the notorious one in which you claimed a local strip club, instead of Live Nude Wrestling, was offering “Dead Nude Wrestling.” That one really got people going.

DD: Was the response to “Dead Nude Wrestling” real? It sounded like it, but how can people be that stupid? The bridge response was real, because that came from a guy at {South Philly composition and print shop} Comp Art and one or two of our writers. I wrote a mock travel review about a horse barn turned into a 400-room luxury hotel, and got a call asking how to get in touch with them because they wanted a new place to get dinner. I deliberately never labeled my fiction as such. Why did I want to create that kind of confusion or at least uncertainty in the people reading it? I don’t know. I think because humor is our saving grace, and that kind of leg-pulling, when it works, is what humor should be doing. Odd, though, that what seemed to me blatant humor was often read with such serious intent. Oh, I had a short story turned down by a little Pennsylvania mag because I’d forgotten to label it “fiction,” and they said they didn’t accept true stories—that was “Memento,” that one about the guy in West Virginia who always laughed at coal.

BLVR: While your style is absolutely unique and recognizable, all your books to date have been radically different, from the Midwestern magical realism of Dead Man to the brutal nihilism of No Bike to the stories in Back Alleys, which are all over the place, though all undeniably your own. That’s not really a question.

DD: But it’s, again, deliberate. I don’t think in “genre” terms, can’t even stand the word. Writing two things the same, or galloping through a “series” would bore the shit out of me. Every tale should be unique. Hmmm, that’s a pretty limiting statement.

BLVR: That said, where are you headed with this next novel—the one that’s driving you nuts?

DD: It’s about a math genius woman, about thirty-two, whose father wanted her to be the new Goedel, and when she failed at that level she found a way to turn off math to the point where she can’t recognize a simple equation. But she has, or think she may have, another weird ability that leads her to disasters. She’s alcoholic, oversexed, gorgeous and often nasty but hates herself for that, usually. Two problems: how to identify this ability through lab work at a hospital, keep it scientific, without drifting into the paranormal. And how to portray somebody who’s an order of magnitude more brilliant than me—I can’t do any advanced math. As for where it’s headed, God knows. That’s why it’s driving me nuts. Again, the character took over and changed the plot several times; I’ve had to ask her questions about her motivations and outlook, and her answers make me love the hell out of her.