“When are we simply imitating, and when are we metabolizing learnings into our beings in a way that makes them, then, authentic parts of ourselves?”

Forsyth Harmon and I met a decade ago at Columbia University, where we had both begun studying creative writing in the graduate program. She was tall with a blunt bob, imposing in her leather jacket. I remember being intimidated until we bonded over shared similarities—we both grew up in small towns in the late nineties and early aughts, when the media inundated us with damaging messages about the female form. Ten years later, I opened her debut novel Justine and found myself thrust back in time, surrounded by magazine ads of emaciated models, hyper-aware of my body and its deficits. In Justine, it’s the summer of 1999, and Ali is a disaffected teenager who suddenly befriends the eponymous Justine, a tall, dark-haired and blunt-bobbed teen. As Ali and Justine’s friendship quickly escalates, an unsettling energy takes over the book. These girls are like so many others of their age—drawn to self-destruction, obsession, malaise, and desire—and yet Harmon makes their preoccupations hyper-specific through detail and image.

Though Justine is Harmon’s debut novel, she has been a published illustrator for years. Most notably, her images accompany Catherine Lacey’s The Art of the Affair (2017) and Melissa Febos’s forthcoming Girlhood. Harmon’s line drawings are always precise and delicate. Often, she draws everyday objects—an opened pack of Uno cards, a cat stretching, a wilted bouquet—with such exactitude and care that they ask the viewer to stop and look again. To really examine.

In this same way, Justine demands your attention. The slim novel is populated with line drawings that require you to look. The image and the text vibrate together and apart, requiring the reader to find the connections, to excavate hard-earned truths. Over the course of a few days, Forsyth and I chatted online about writing autofiction, destructive female friendships, eating disorders, learning through imitation, and the decision to withhold interiority in the writing of Justine.

—Crystal Hana Kim

I. MOOD BOARD

THE BELIEVER: Justine is a slim, striking, and spare illustrated novel. What came first for you, the art or the writing?

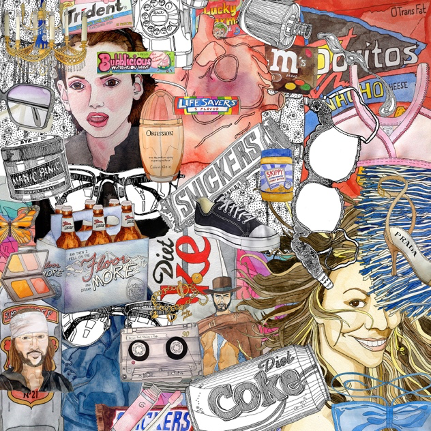

FORSYTH HARMON: Thank you. The story was inside me from the beginning, but at first, I was better able to pull out the images, sort of vomiting up a mess of illustrations: renderings of people and things that felt integral to the narrator’s world. A visual first draft, or maybe you’d call it a mood board. Here’s what that looked like:

Nothing spare about it! But you’ll see some of the objects and ideas carried through to the book: a can of Diet Coke, Walt Whitman, a cop car.

After that initial purge, I moved back and forth between writing and drawing. It was an emotional process for me—the story is autofictive—and I was grieving a lost friend. I think I was also grieving the effects of an ideology—beginning to understand and process how the conservative values she and I grew up with may have impacted our ability, as women, to be true friends to one another. It was so helpful, working through all of this, to be able to move between images and text. The process of writing tends to rile me up—it uncovers things I might have otherwise left alone—while, for me, drawing is super mellow. It’s not cerebral. It gives me time to just settle down and process whatever I may’ve kicked up in the writing.

BLVR: This visual first draft is fascinating. Thank you for sharing. I imagine there must be an immense pleasure in being able to switch between the mellow work of drawing and the harder work of writing. So you started with these drawings, which were rendered from your own life. When did you realize you were working on an illustrated book? When did the work move toward fiction? I’d love to hear more about the creation of Justine and how it might have changed over time.

FH: I always knew I wanted to do an illustrated book. I made a series of illustrated girl detective books as a child, and, as a teenager, went on to make a lot of zines. You can probably see how that black-and-white photocopied look influences the aesthetics of Justine.

Following that visual first draft, I began to work on the narrative for Justine, bringing words together with full-color images. I was in an MFA program at the time, and I struggled with doubt, especially following my final thesis conference, in which I was told by a prominent novelist to drop the images and write a traditional novel. I followed that advice and rewrote Justine without images. It didn’t quite work. Frustrated, I returned to the original illustrated project. The time away from it had been helpful. And I now had stronger skills with which to tackle my original intention. I moved toward a more consistent, minimal aesthetic, and in addition to rewriting, I redrew everything in black and white. I want to emphasize this point, because I think a lot of us struggle here: my original intention was correct, but I lacked the confidence and skill to execute it. I didn’t have to change my project. I had to practice. Too, Justine will become the first part of an illustrated trilogy, the second and third parts of which derive from that traditional novel draft.

BLVR: I’m so glad you returned to the original illustrated project. I believe the images and texts in Justine rely on each other to tell the full story. My projects often change completely from draft to draft, so I want to emphasize your point about intent, improving skills, and knowing that the work isn’t futile. The work you put in (whether or not it ends up in the final draft) allows you to get to know the characters, story and overall project more deeply. That’s never fruitless.

There’s a precision to your drawings and your writing. In my experience consuming Justine, physicality and detail unite these two forms. How do you want the illustrations and writing to work in this book?

FH: I got and continue to get feedback that the writing lacks interiority. Initially, I tried to address this feedback by adding some, but it didn’t feel honest. What did seem to work was making drawings from the point of view of the narrator as another way of representing how she saw and felt the world: up close, without much perspective. The cult objects of nineties adolescence emote for her. And so a makeup compact opens, a cassette tape unravels, a piece of loose-leaf crumples, a Tamagotchi pet expires.

II. WISTERIA

BLVR: You said that this novel is autofictive, and that the act of writing allowed you to realize the extent and faults of your friendship with the character that Justine is molded after. Your novel explores a fraught and elusive friendship between two teenage girls—the narrator Ali and Justine, who she meets working at the local Stop & Shop. What is it about female friendships that compels you?

FH: I hope it’s not too cryptic to answer this question with a passage from Tarjei Vessas’s The Ice Palace. Here, Siss and Unn hold up a mirror to their faces, cheek to cheek:

Four eyes full of gleams and radiance beneath their lashes, filling the looking-glass. Questions shooting out and then hiding again. I don’t know: Gleams and radiance, gleaming from you to me, from me to you, and from me to you alone—into the mirror and out again, and never an answer about what this is, never an explanation. Those pouting red lips of yours, no they’re mine, how alike! Hair done in the same way, and gleams and radiance. It’s ourselves! We can do nothing about it, it’s as if it comes from another world. The picture began to waver, flows out to the edges, collects itself, no it doesn’t. It’s a mouth smiling. A mouth from another world. No, it isn’t a mouth, it isn’t a smile, nobody knows what it is—it’s only eyelashes open wide above gleams and radiance.

BLVR: Cryptic but intriguing. The narrator Ali is obsessed with her new friend Justine. She copies Justine’s habits—from the magazines she reads to the yogurt she consumes. It reminded me of how vulnerable we are in our teen years, how easily consumed we become with others’ identities. Everything about being a teen feels fraught, and your sense of self is marked only in relation to others. What is it about imitation that is so alluring?

FH: It’s a little thing, but when I think about the friend I lost, I reflect on how I wore my hair like hers for years after she was gone. Was that her haircut or mine? The eating disorder definitely became my own.

I have a young son, and I see how he learns through imitation. We draw together almost every day, and we talk a lot about color. Then I overhear him tell his dad: “That’s not periwinkle Dada, that’s wisteria.”

They say Matisse had to paint like Rembrandt before he could paint like Matisse. He had to imitate the masters who preceded him before he could come into his own mastery. I guess the question is, when are we simply imitating, and when are we metabolizing learnings into our beings in a way that makes them, then, authentic parts of ourselves? I see this with reading and writing, too. Right now I’m rereading Toni Morrison’s oeuvre, and I can see how my sentences start to read very much like Morrison’s. Then I revise and the text no longer reads like a Morrison imitation…but there’s still some trace there of what I learned from her.

BLVR: You mentioned an eating disorder—how it began as an imitation of this lost friend and then became your own. Similarly, both Ali and Justine are self-destructive, particularly with regards to their bodies. They deny themselves food, purge what they do eat, and track their weight. Why is weight loss and thinness such an obsession for these two characters?

FH: It would be easy to say that the European beauty standard drives the characters’ obsession, and that’s certainly part of it. They spend a lot of time paging through Vogue, measuring themselves against the images they see. They also imagine beauty as a way out of their small, conservative town—like if they get tiny enough, they might fit through some narrow, elusive opening into a world of fame, luxury, and freedom.

The word freedom is important. The developed female body comes with a lot of responsibility—it is often pregnable—and baggage, from gender role expectations to the weight of male—and female—attention, commentary, and violence. Melissa Febos writes about this beautifully in her essay “The Mirror Test,” part of her Girlhood collection (which I illustrated), coming from Bloomsbury on 3/31. You can also read it in The Paris Review Issue 235.

The illusion of control is also material here. During adolescence, our bodies, our minds, our worlds—and the way the world treats us—are changing. How seductive, to think that simply by controlling what we do or don’t put into our bodies, we can gain control over that chaos. Self-starving isn’t that different from drinking or using drugs. It both allows for an immediate change in consciousness, and, when it becomes an addiction, narrows the radius of consciousness to a very small set of concerns. What do I weigh? What do I want to weigh? What did I eat? What will I eat next? When? Melissa Broder captures this state of mind with astonishing accuracy in her novel Milk Fed.

III. “TURN YOUR SCARS INTO STARS”

BLVR: Ali feels stuck in this town, in her small life. She seeks freedom through starvation and imitation. She’s also hyper aware of material signifiers of class and privilege. For example, while working at the Stop and Shop, she notices a girl twirling a key chain with “a big yellow Northport Yacht Club floating fob, a BMW logo. She was probably wearing real Chanel Vamp nail polish, not knockoff Revlon Vixen. I didn’t breathe until she was out of sight.” What did you want to accomplish with this specific focus on consumerism and brands?

FH: Ali is a working class teenager in a suburban culture which simultaneously celebrates material displays of wealth and forbids straightforward discussions about class. What brands someone wears, and the neighborhood in which they live, are perhaps the only ways in which Ali is able to make class distinctions. This way of seeing the world is true to my own experience. I’ll never forget being in one of my very first undergraduate seminars and seeing a classmate wearing real Prada shoes. I was shocked to see them on the feet of a girl my age. I immediately understood that while I didn’t grow up poor, I didn’t grow up rich, either.

BLVR: Are those the Prada shoes?

FH: Those are indeed the very shoes.

BLVR: Going back to class—I can see this tension between being aware of material wealth but not being able to talk about it in Ali’s observations. She is always noticing, but she doesn’t reflect more deeply on these class distinctions, even to herself. This goes back to what you referenced earlier about how you didn’t add interiority into the novel because it felt untrue to the character—and untrue to your lived experience. Does Ali’s interiority change throughout the trilogy as she (presumably) gets older?

FH: I love that you ask this question about the trilogy because yes, your guess is exactly right: each book takes place ten years after the previous, and Ali matures accordingly. In the second book, she is coming to terms with repressed trauma, and her interiority grows with that awareness. In the third, she begins to negotiate recovery, together with the sensitivity and empathy—for herself and others—that come with it. Each book gains perspective.

BLVR: Oh, that’s fascinating. I imagine it’ll be rewarding for the reader to see Ali’s interiority deepen as she reckons with her trauma. As I said earlier, Justine is quite a slim book, so I imagine you could have formed Ali’s story into one longer novel. Why did you decide on the trilogy form?

FH: I read a lot of series books as a kid, like The Babysitters’ Club. I also loved the Christopher Pike mysteries, and those covers! As an illustrator, I think about the book as an art object. There’s something about three slim black cloth-over-board books—each named for a different woman—that resonates. The first third of my own life has been very much defined by intense but episodic relationships with women.

BLVR: I can see the trilogy making a beautiful collective art piece. I love that we will be able to learn about Ali through her relationship with others, since she very much seems like a character who processes through comparison. Going back to this first book, what do you hope readers and viewers will get out of Justine?

FH: In terms of form, I hope the book reopens interest in what illustrated literature—which hasn’t really been in vogue for a century—can do. In terms of content, I hope it inspires reflections on how both provincial conservatism and the European beauty standard disable intimate relationships. And in terms of how this book contributes to the project of autofiction—well, it’s easier if I tell a story. When I was a kid, I got a necklace at the thrift store. The charm was gold-plated and star-shaped, and on one side it said “TURN YOUR SCARS,” and on the other: “INTO STARS.