“Most people who do autobiography, myself included, it seems like they’re trying to work something out. Like we’re trying to do therapy on ourselves. In that light, it’s true: we’re sort of suffering over something and working on that.”

Three of Gabrielle Bell’s Fears:

Authority

Laundry card machines

Getting caught up in the question of non-fiction versus fiction

I’ve been reading Gabrielle Bell for years. Gabrielle Bell’s books, I mean, though sometimes it does feel like I am reading the person, like I am seeing right into her life and mind.

This is the trick that she’s perfected over time, starting in the late 1990s. When you read the cartoonist Gabrielle Bell’s stories, especially the more obviously autobiographical ones, you feel like she’s giving you the gift of her world, a candid, sometimes embarrassing, often entertaining very close look. But, of course, this “trick” is a mixture of a variety of different skills and talents, honed over time: drawing, styling, observing, shaping, inserting, withholding. Her books and stories regularly engage with the pleasures and anxieties, often mixed, of living in our contemporary world. A passion for and fear of the internet; an investment in and distaste for social interaction; a constantly ebbing-and-flowing sense of self.

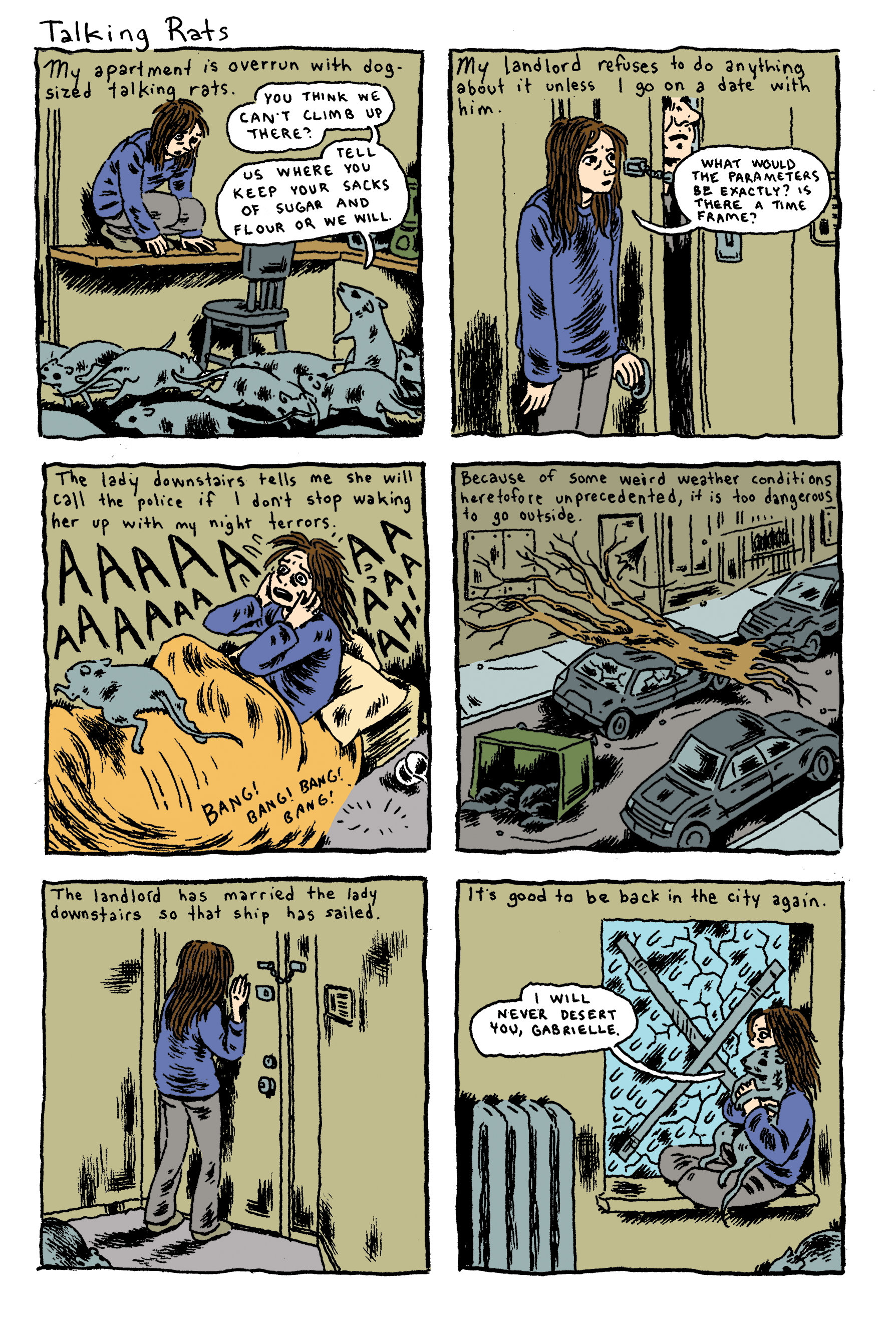

Inappropriate, Bell’s latest book, is a collection of stories once again featuring this Gabrielle Bell persona, who keeps resisting, and being resisted by, the world around her, even as she’s all in, an Emersonian transparent eyeball set loose in a modern, mostly urban landscape. The book has stories featuring bed bugs, fishermen, talking rats, and, of course, our inscrutable narrator. In one comic, having slipped on an icy pavement, she is pinned under her bags of groceries, worrying that this is a punishment for having returned a bruised apple. The final panel pictures her still splayed on the ground, expressionless and looking up at the sky. “Or maybe,” the narrative reads, “there was some other more terrible thing I’d done that I’d forgotten all about.”

Talking to Gabrielle Bell both is and isn’t like stepping into one of her comics. There are no talking cats or bears to cuddle with. But you do get to experience what happens when you spend a few hours with someone who spends a big chunk of her waking life thinking about what it means to be a person in the world. OK, a particular kind of person; in this case, a forty-something-year-old cartoonist living in Brooklyn with a bunch of published books to her name and other people’s pets flitting in and out of her life and a love of prose fiction and a fear of laundry machine card machines. It felt, come to think of it, a bit like being in an Edward Albee play.

—Tahneer Oksman

THE BELIEVER: You’re currently working on a new graphic novel focused on dating. And none of the stories in this book, Inappropriate, are obviously about dating, but a lot of them seem like they could be metaphors about the experience of dating, or oblique references to it. Do you agree?

GABRIELLE BELL: [Flipping through the book.] Let me see. Here’s a story [“The Nicest Dog”] about shopping for a dog. I go to the pound, and I fall in love with the dog, and I’m like, do I want to keep this dog? As in, do I want to marry this dog? And here’s a story [“Cat”] about this cat that comes to my apartment, and we have some kind of psychosexual drama happening and then we get into a fight.

Here’s me and a guy walking through the city together [“Late March”]. We’re basically on a date. And then there’s “Carolyn,” which is a story about a character based on a guy I was dating. This was an experiment—it’s a fictional story. I was experimenting with composite characters.

And “Little Red Riding Hood” is essentially a dating story…

OK, you’re right.

BLVR: Maybe I was influenced by the story early on in the book, “Mr. Prince,” which is not about dating per se, but it is about what your narrator calls “my princess dreams.” Could you describe the narrative?

GB: It was a fantasy in which I meet a homeless guy who turns out to be an estranged prince from the House of Windsor. It’s a princess-kisses-the-frog kind of story. It also turns out he’s a “woke” feminist and educated and enlightened in the traditional Buddhist way. He’s also politically enlightened; he goes to protests. He’s just the ideal man, and he happens to be a prince.

BLVR: I found it interesting how most of the story is about his evolution: his intellectual evolution, his travel story. There’s almost no interaction with you, the narrator. It struck me, thinking about this story, that the collection is largely about the push and pull between dependence and independence.

GB: Because at the end of story, I say I’m against marriage, and he says, me too, but we have to get married for political reasons. The fantasy is being forced into this traditional thing that as a feminist you’re not supposed to want.

BLVR: Maybe you could also read it as a fantasy about falling in love with the person you want to be.

GB: So, you’re saying, the prince is actually the protagonist, which is actually me. I’m the prince.

BLVR: Well, a lot of these stories seem to be about that theme: of wanting to be your own hero, self-sufficient, but also just struggling, even with basic self-care. For example, there’s your one-page story, “How Do You Do Things?”

GB: Just doing normal things that everybody else does seems incredibly complicated to me. The simplest thing. Even doing the laundry sometimes seems labyrinthine.

Things are hard.

In the story, I have to do laundry. I take it to the East River but because of a toxic spill I have to go to a laundromat, and I just can’t figure things out. So I end up walking home with my dirty laundry. The joke is that I don’t know how to do laundry. I don’t know how those laundry cards work, and I’m too embarrassed to ask anyone to explain it to me because I should have learned by now. It’s like when you’ve known somebody for a long time, and you still don’t know their name, and it’s too embarrassing to ask.

Rather than make it easy and ask someone, I end up doing things the long, prodding, laborious way.

BLVR: This book has fictional and autobiographical stories interwoven throughout. How would you describe it, in terms of genre?

GB: I think of all my work as closer to non-fiction. But I’m afraid of getting caught up in that question of fiction and non-fiction. I don’t know if I want to go there.

BLVR: Maybe we could approach this question from a different angle. I was just reading about Italian author Natalia Ginzburg, another writer who often played with those boundaries. At one point, reflecting on a piece of fiction she wrote, in which she drew heavily (perhaps too heavily, she thought in retrospect) from her life, she says, “When we are happy our imagination is stronger; when we are unhappy our memory works with greater vitality. Suffering makes the imagination weak and lazy.” Do you agree?

GB: Most people who do autobiography, myself included, it seems like they’re trying to work something out. Like we’re trying to do therapy on ourselves. In that light, it’s true: we’re sort of suffering over something and working on that.

I tried out fiction a lot when I was younger, and it embarrassed me because it didn’t feel true. It felt like there was this layer caked on that was unnecessary. I remember reading Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and trying to figure out which character was which person in real life. Which character was Neal Cassady and which was Allen Ginsberg? I felt like it was distracting me from the story. Why not use real names?

In my book Lucky, my early autobiography, I was changing all the names and everything else was pretty much true. And even that felt forced, or fake. And then, thinking about Kerouac made me realize why. I don’t want to say it’s a lie, but there’s a pretension about it.

There is a major prejudice about autobiography, partly because so many people use it badly. But the sincerity of it is important.

BLVR: The reader’s expectations.

GB: Yeah. I think Kerouac should have chosen fiction or non-fiction. Any kind of roman à clef takes you out of the story. A lot of fiction is trying to hide something. This is not to say—I love fiction, it’s the greatest thing in the world. But there’s a place for it, and there’s an equally important place for autobiography. With autobiography, it’s like showing the paint strokes. At some point, you can’t hide.

BLVR: Do you read more fiction or non-fiction?

GB: I read more fiction. I do think there’s an important distinction between the two. Like in my story, “The Forty-Three-Year-Old Spider.” It’s a fictional story, of course. I’m not a spider. But I am forty-three years old. And the spider is concerned about a lot of the things I’m concerned about (aging; attractiveness; relevancy). So, in a way, I’m using the spider to make fun of myself. But even though I’m using the story to illuminate my personal issues, the fictional aspect helps show my personal issues as universal ones, too.

Fiction is telling the truth with a mask. You wear a mask so you can tell the truth. In autobiography, you tell the truth without the mask—you’re vulnerable and naked.

BLVR: You have a lot of animals in this book. They’re often anthropomorphized, like in the spider story or the story with the cat that comes over to your apartment holding a toolbox to help you with your “mouse problem.” Your work has always been interested in animals, but they feel even more central here. Why do you think that is?

GB: Have you ever read Edward Albee’s play, The Zoo Story? It’s two people on a park bench talking. One of the characters—Jerry—he says he can’t connect with anyone. He’s trying to connect with people, but he can’t talk to anyone because nobody understands him. And he talks about how he’s just been to the zoo. He says, if I can’t connect with people, maybe I can start with animals, and I’ll work up from there.

Animals, for me, are like that. They’re a bit easier to connect with than people. Interacting with them is a little bit simpler, like training wheels or a tricycle or something.

BLVR: A lot of the animals in the book are borrowed animals or animals that are kind of thrust on you.

GB: I do a lot of pet sitting. In my building, there’s a cat on the fourth floor, and a dog on the fifth floor. There was another cat on the third floor that died. (I didn’t kill it.)

I don’t have much of a schedule. I work at home, and I don’t have a lot going on, so people can always rely on me to look after their animals when they leave town.

BLVR: This is also a book about returning to the city, to Brooklyn, right?

GB: All these stories are from the last ten years so some of them were from before I left the city, and some were done when I was away from the city, living in Beacon, New York, and some, equal parts, take place after I came back. But I think most of my work is urban.

BLVR: I want to talk a bit about form. I know you like using formal constraints in your work—panel boxes, sometimes a set number of them. In this collection, you have some one-page stories and some longer ones. Could you talk a bit about the process of giving the book its shape?

GB: I think the only formal constraint in these stories is the boxes (the panels). It helps that they’re square, so they can be moved around. I used to try to focus on having them fill up the whole page, but now I’m willing to let the story stop in the middle of the page. I think that came from doing comics on the internet. It can just be any length.

With comics made up of panels, it’s pretty arbitrary to say that the story has to end at a certain point. It’s like if you were a writer and you told yourself that the words had to go down to the end of the page. Why would you do that?

BLVR: I was thinking of the one-page stories as palate cleansers. Or vignettes. Do you think of the shorter pieces in a different way?

GB: Every story is as long as it takes. Sometimes it’s seven panels and that’s a problem, so I’ll add until it’s eight or nine panels to make it work. Or I’ll move the title, or make “The End” a panel in itself. Sometimes the title will be two panels long. Once in a while, when it feels like a panel needs to be extra big, I will double its size. And sometimes, very occasionally, I’ll have smaller panels.

I don’t think it’s irrelevant, but I tend to focus more on the storytelling and rendering than the design, even though the design is part of the storytelling. But it is something I tend to put on the backburner.

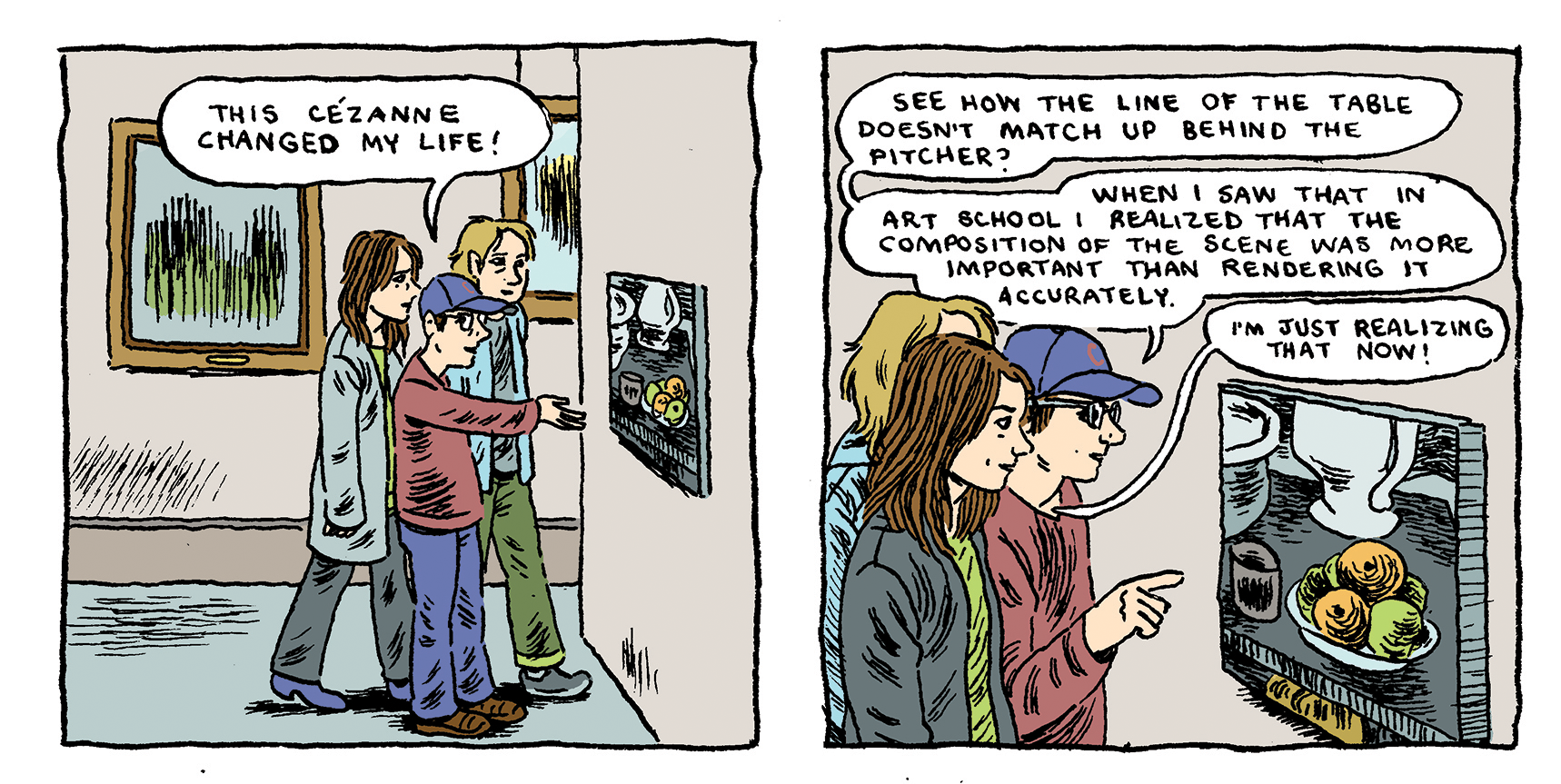

BLVR: I want to talk about the “John Porcellino” story, where you go together to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés. You have this great panel, when you’re on your way to see the Duchamp, and you stop to look at a still life by Cézanne. John says the painting changed his life—how in art school, it helped him see “that the composition of the scene was more important than rendering it accurately.” And you’re really wowed by this. You say, “I’m just realizing that now!” as you’re looking at the painting together.

GB: I was. I was realizing it in the moment that he was showing me and telling me. That was a real jump for me—a revelation. I’ve had moments like that throughout my life, where there’s a shift.

I do get so caught up in rendering, and I lose the whole point. I think I wasted years of my life just trying to get an elbow right while the rest of the image was just wrong.

BLVR: So this was a hard-won insight?

GB: Yes, I had to learn the hard way. I remember being in community college for a brief time, a semester. I started to take a design class. There were two teachers, and one of them was teaching us a color wheel. And I thought, “This is so dumb,” and dropped out. I completely regret it because all of my contemporaries who understand design have such an edge. Not just in comics, but in illustration. This is what I missed by not taking that class.

Of course, ultimately, everything is grist for the mill.

Here, it was John’s excitement that affected me. It was so thrilling because he had seen something about this painting in a textbook a long time ago, and it caused an alteration in his mind permanently. Then, when he saw the painting in person—and he wasn’t thinking about that particular thing, that memory, at that moment—but this idea jumped out at him that had caused a paradigm shift for him thirty, thirty-five years ago. That excitement poured out of him onto me.

BLVR: It’s also a nice moment of learning from, but also with, another cartoonist, another artist. Have you had mentors?

GB: I’m jealous of people who have had and who have mentors.

When I was first starting to do comics, I really wanted a mentor. But there were so few women comics artists. I didn’t know any. And I tried with men cartoonists, and I really did learn a lot in a general way. A lot of it came from flirting and just being a young, clueless female to these older, nerdy men who didn’t otherwise get a lot of female attention. I think I kind of gleaned a lot of mentorship in a way.

My method has been a lot of gleaning, just picking things up, like with John Porcellino. Picking up pieces here and there, harvesting here and there. It’s chaotic. And it has often been from men. I think the pattern was set, from an early age, probably because I had three brothers and a stepdad who was a very formidable personality. And my mom was very quiet and unauthoritative.

BLVR: In the collection, you have lots of scenes with women, especially in the first half. Like the Carl Jung reading group in the eponymous story. That story sets the tone for the whole book. It made me think of female companionship—like being with animals—as a kind of counterpoint to the alienation that the narrator often feels when she is alone or when she is seeking men or even just fantasizing about them.

GB: I think with women I feel more on an equal footing. It’s more lateral. I learn a lot from women, though I don’t look up to them as mentors in this primordial way.

During the mid to late 2000s, there was a big flux of women cartoonists that came pouring in. There had been something nice about being the only girl—one of the only ones—and it took a while to adjust. But once I adjusted, it became a really important community. Especially in the past ten years or so, there have been so many female cartoonists come up, and I’ve become good friends with a lot of them.

For me, with women, it’s more about community. With men, it’s more about mentorship.

BLVR: Have you ever seen yourself as a mentor?

GB: It’s not a comfortable position for me. I don’t like it, I think because I didn’t have any mentors in a traditional or safe way. I just picked up bits and pieces here and there.

It’s the same reason I’m not comfortable with teaching. I didn’t have much of a formal education. I think with mentorship, it’s like a relationship. And in my early years I had a hard time with any relationship. Friendships were fraught, relationships were difficult. So a mentorship would have been another difficulty.

Having skipped over being menteed, it’s hard to go straight to mentoring. I think there’s some resentment in it. But also, I don’t want to say anything authoritative; I don’t want to be anybody’s teacher. I think that’s a huge responsibility, and I don’t think I’m equipped for it.

BLVR: So what’s it like being in a classroom with you as a teacher?

GB: I don’t like it. Probably a big part of it is arrested development. But also, not everyone wants to be a teacher or mentor.

BLVR: Your work is authoritative, though. There’s a confidence not only just to how much you’ve published but also in the way you set the tone and stick to autobiography in a non-apologetic way. Your voice is strong.

GB: Within the parameters of my work, yeah. But I’m only just becoming more aware of how the things I say and do in real life have an effect on people.

Sometime in my late twenties and thirties, I became a figure in comics who had some kind of quote-unquote power. But I also felt powerless; I did, and I still do. I’m only now learning the effects of words.

When I was a young cartoonist, if an older cartoonist had said some cynical or backhanded or flippant thing, I might remember it to this day. Part of me is still that young person being affected by all those things other people said and part of me is this older person affecting other people. Which is to say, I’m too sensitive for this stuff.

BLVR: One thing I’ve always been struck by in your work is how candidly and directly you attend to your material circumstances—the costs of things, including, in two of the stories here, basic healthcare costs. Could you talk about making a living as a cartoonist?

GB: I grew up poor, and I never really learned how to sell myself. I was never a good businessperson, I never learned how to do illustration. I don’t like teaching. I pretty much live off my comics. So in that way I’m doing pretty great, even though I don’t have much money.

Cartooning is time consuming; that’s one reason that it doesn’t make a lot of money. But also, in a way, comics just haven’t caught up with the market. A comic strip in a magazine will pay, like, $100, whereas an illustration in a magazine will pay $700. Even though an illustration is just one panel of a comic strip. Those who do illustration say it’s like doing one panel of comics without having to write.

So it’s about the time that goes into the work. It might take a week to do a comic strip whereas it will take a day to do an illustration. And making a graphic novel might take five years while it might take a year to write a prose book, but the advance will be the same.

That said, most cartoonists I know are doing fine. They have a Patreon account to supplement or maybe they teach or do illustrations, which is not much different from most writers or artists. Very few people make it huge and become famous.

I don’t think making comics is a bad life choice, and I don’t think it necessarily leads to a life of poverty. It does take more time to make comics, though, which means you end up producing less. Maybe if you’re a writer you put out a book every two years, and if you’re a graphic novelist, you put out a book every four years.

BLVR: A lot of the stories here feel like they incorporate these mini autobiographies of your body. Like when you’re fantasizing about rolling around with polar bears, readers really get a sense of the bodily pleasure.

GB: Or the bodily pleasure of scratching a bedbug bite. Or rubbing the cat’s belly.

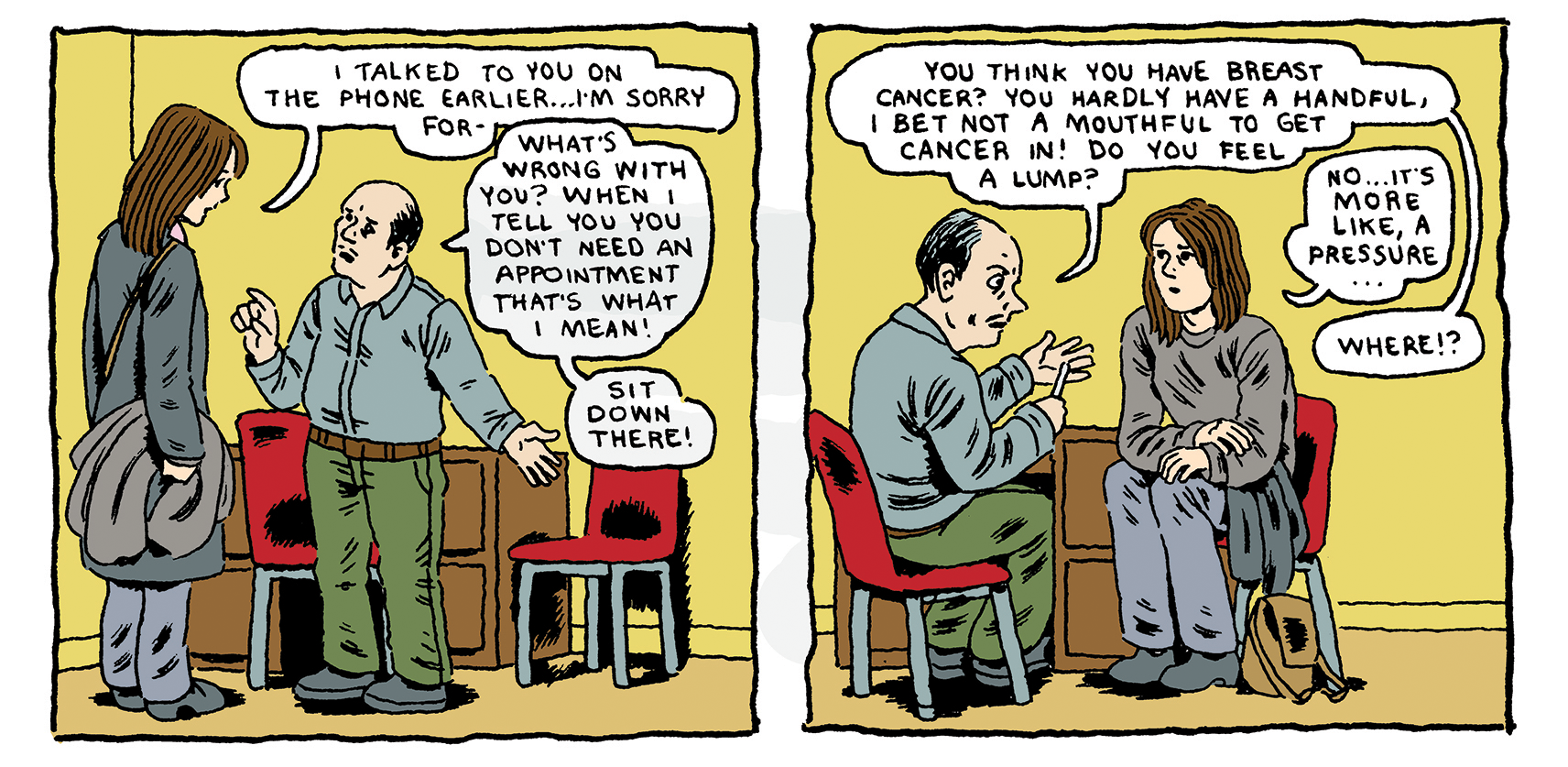

BLVR: Exactly. I was also thinking about two powerful horror stories in the collection that are about visiting healthcare professionals, a dentist (“Dentist”) and a doctor (“Doctor Emmanuel”).

GB: This doctor was out of control.

BLVR: He’s really out of line. At one point, you’re worried about something you feel in your breast and he says to you, “You think you have breast cancer? You hardly have a handful, I bet not a mouthful to get cancer in!” And yet, you seem weirdly indifferent to his behavior, at least in the midst of the scene.

GB: It didn’t even occur to me to get angry. Because of the futility of it. It’s like these people are just accidents. I get angry on the first page of the comic, when he tells me over the phone that I don’t need a mammogram, and I yell at him. And then, when he yells at me in person, I feel chastened.

BLVR: There’s a sense of you—of your narrator—feeling like she’s not deserving or worthy of this other, awful person’s time.

GB: Yeah, that fear of taking up too much space.

BLVR: But then the authority comes up in the comics—in the drawing and writing of the experience, which feels defiant and weirdly triumphant.

GB: I think it’s part of why women have done so well in comics. I don’t want to talk about women too much—I get myself all bogged down. But there’s something about publishing on the internet. Drawing a comic and putting it online. There are no gatekeepers.

If it’s even a little bit good, then you get attention for it, which gives you the energy to do a little bit more. That’s really good for people like me, who are afraid of authority, who are afraid of everything. With the internet, I can just go straight to the source, straight to an audience, without having to answer to any middleman or agent or anything.

BLVR: Did these comics first come out on your Patreon?

GB: A lot of these preceded my Patreon. A lot were on my blog. A lot were also done for Vice and The New Yorker and different anthologies. “Cody” was done for Kramers Ergot. The spider one was on Spiralbound for Medium. Little Red Riding Hood was for The Paris Review.

BLVR: Did you have to edit them a lot?

GB: A fair amount.

BLVR: People don’t always seem keyed into the humor in your work. This volume is often hilarious. Sometimes it’s the mood or tone, but there are also a fair number of punchy lines as well as understated ones that kept making me laugh out loud.

GB: When I was younger and the only female around—I mean, there were others, like Julie Doucet and Meghan Kelso, but not so many in San Francisco, where I lived. There was the feeling of being invisible, not just because of being a woman. Eventually, I felt like if I cultivated humor, it would bring attention to my work.

I didn’t start out as a humorist. In a way, with humor and autobiography both, I felt like I was selling out. My earlier comics tended to be more fictional, and I wanted to do somber short stories. But fiction, as I mentioned before, felt false and insincere. So all that stuff fell away. Doing autobiography and comedy didn’t feel like quote-unquote high art, which is what I had set out to do.

BLVR: But the humor in this book feels confident, maybe more confident even than in any of your previous books.

GB: There’s a kind of cynicism that comes with aging. In some ways, you know what’s going to happen, you can predict it. Humor comes from seeing things happen again and again. So it’s easier to be funny when you’re older because you can comment on the patterns. When you’re young, everything is new and big and important.

Did you hear Joan Rivers on NPR’s “Fresh Air” the other day? She talked about how she used humor to cope with the most horrible things in her life, like her husband’s suicide.

BLVR: When I read your work, I sometimes think about the exhaustion that comes from being an observer. The kind of elation and fatigue that comes from being the person who’s paying close attention, whether to your own life or other people or the world around you as it unfolds. Do you often feel like an observer?

GB: I think it’s only in the comics; I go into observer mode. I do a “July Diary” every year, where I make a comic every day for a month. During that month I’m just writing down every single thing that happens to me and anything even remotely interesting that anyone says. I put it all in my notebook and then try to make something of it. I try to make a little story of it, every day. That is exhausting.

It is something I used to do all the time, especially when I was younger. Everything felt so powerful, and I would try to turn it all into stories, to make meaning out of it. I used to keep a comic diary all the time. Now, I just do it once in a while.

I don’t think it’s possible to be just observing all the time. That’s one part of the creative process. And then when you’re creating something, or making something out of those observations, you really have to turn that observing part off.

BLVR: Are you saying, with time you’ve learned better ways of spending your time?

GB: I was thinking of it more as laziness. But laziness as a practical thing, in that evolutionarily we are lazy when we perceive a thing being done is not worth the effort—that we have to preserve our energy for something else, something more important.

BLVR: So it’s more about spending the time that you have doing the things you enjoy or the things that have meaning?

GB: Yeah, it’s like rationing, rationing the energy and time that you have.