“I felt like when Trump was elected, we were all just living through history. I still feel like that. We’re done with even being funny about it. Everyone is just exhausted.”

Work about the experience of motherhood:

Has to do with sex

Requires your own space

Needs to be elevated to high art

About a decade ago, I picked up a small, rectangular-shaped book of comics with a dayglo reddish-and-yellow cover, titled Girl Stories. Cartoonist Lauren Weinstein’s second book, published in 2003, includes such classic titles as “Am I fat?” and “How to really get a boyfriend.” Like much of her work, the book pushes boundaries, between humor and absurdity, between autobiography and cultural and political commentary. The cartooning style itself was something of a revelation: how could something, all at once, look so carefully crafted but also so spontaneous and free? How could a work that appears emphatically earnest also make me feel like a joke was being played, at least a little bit, on me, and on all of its readers?

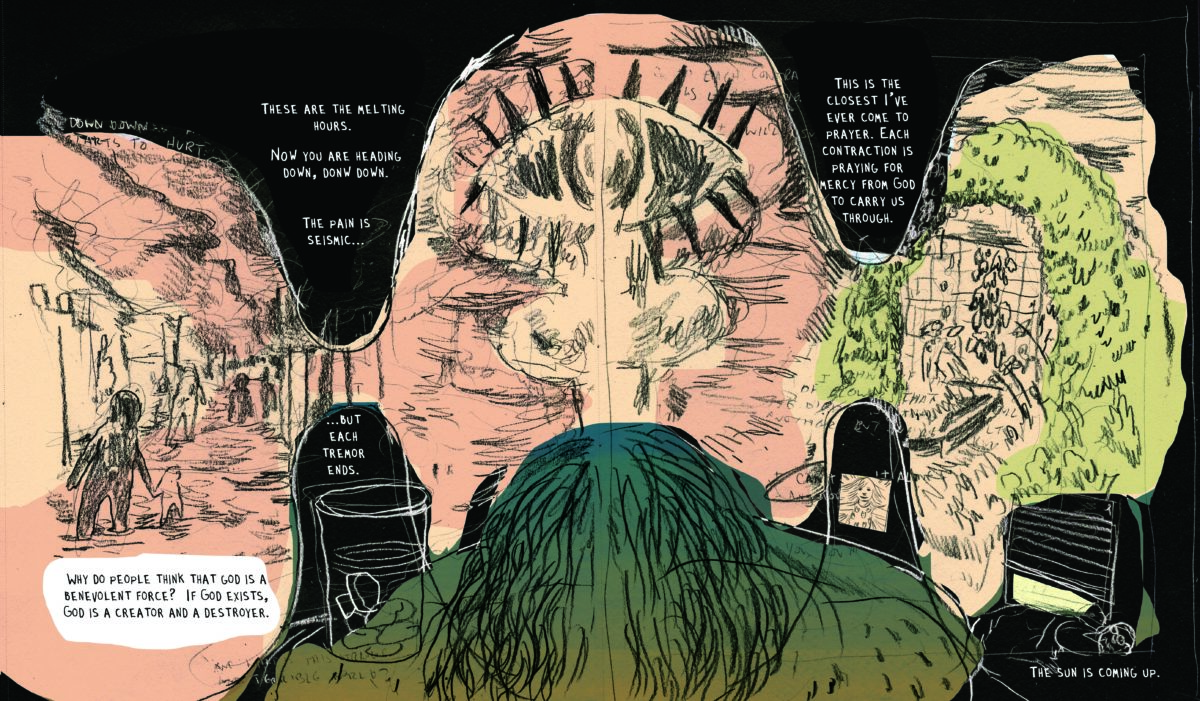

I’ve since had the opportunity to engage with the wide range of Weinstein’s oeuvre, from her “Inside Vineyland” cartoons—an early strip she did for Seattle’s The Stranger—to her more recent sometimes-political, sometimes-autobiographical, often-absurdist strip for the now-departed Village Voice. (I should also divulge: Weinstein designed and drew the cover for my first book, which includes a study of her early work.) Over the last nine or so years, Weinstein has been publishing comics about her experiences of being a mother and an artist for venues that include Nautilus, The New Yorker, and The Paris Review. Her most recent piece, a 32-page comic for Frontier, titled “Mother’s Walk” and recounting in unflinching, gorgeous detail the experience of being pregnant with, and birthing, her second child, has fittingly made it onto a number of “best of” comics lists for 2018.

Several days into the new year, I had breakfast with Weinstein in the posh second-floor café of the Freehand Hotel, just a few blocks from the School of Visual Arts, where she sometimes teaches. While a waiter fluttered around us, the tape recorder apparently making him nervous, we discussed a number of her most recent ventures. Weinstein’s easy laughter peppered our conversation.

—Tahneer Oksman

I. “I feel this too.”

THE BELIEVER: I want to start by asking about your strip in The Village Voice, which you were publishing almost every week from the end of 2016 to early 2018. How did you get involved in this gig? And where does the “normel person” tag line come from?

LAUREN WEINSTEIN: One day I heard from Tom Spurgeon, who was working with the editor from the Voice. They were looking for people to do strips, and he had thrown my name into a pile. When he told me about it, I became obsessed with the idea. I knew the history of comics in the Voice—I knew about Jules Feiffer, and Robert Crumb, and Matt Groening. And I also knew the tumultuous history. I went in with my eyes completely open.

Soon after, they contacted me and asked if I had an idea for a strip. When my older daughter, Ramona, was around six-years-old, she had drawn a picture of this degenerate creature with one eye and seventeen fingers. She’d written “normel person” beside it, misspelling “normal.” I thought it was the perfect name. It’s also now the cover of the mini-comic I published collecting those strips from the Voice. I loved the idea of the “everyman,” a “normel person” being this wacked-out degenerate.

BLVR: You started publishing in the Voice just before the 2016 election, a turbulent, uncertain time leading to an even more turbulent and uncertain era. Did you have a particular vision when you started?

LW: My idea was always to make absurdist commentary on whatever was going on in the Zeitgeist, and then, every once in a while, throw in an autobiographical strip to contextualize things. I didn’t think I would be a political cartoonist; I’m not really a political cartoonist. But when I started to do the strip, I felt like I had to respond to the crazy news cycle, even though it also felt kind of pointless.

Also, I realized going into it that the most productive part of my entire career was when I had my weekly strip, “Inside Vineyland,” for The Stranger in Seattle [from 1998-2001]. That’s when I was really learning how to be a cartoonist. I was in my early twenties, I was on the same page as Chris Ware, and every week I’d get completely schooled. When I got the job at the Voice, I thought, I’m going to do the same thing now; I’ll throw caution to the wind and see if I can just make something every week.

The other thing is that I was secretly pregnant. Eight years before, I had had this period of frustration after giving birth, where it took me a long time to get back into the game. I realized I needed to do this for my creative survival. I didn’t tell the Voice people, but I thought, if there’s something I can do throughout the whole pregnancy and giving birth thing, I bet I can get out one strip a week. Even if everything is totally nuts, I can focus on just doing this.

BLVR: Lots of your strips from the Voice were timely, in the sense that they were responding either to political events going on at the time, to national moods and occasions, or to experiences from your own life. But then you have these completely non-autobiographical, outlandish pieces. Could you talk more about what these out-of-context pieces were doing there, and how they relate to the work of the strip as a whole?

LW: I almost want to axe all of the timely strips. I don’t like them. Some of them are interesting historically, but at times I got too caught up in the moment, which for me is a disaster. Trying to be the smartest one about some sort of historical event going on is never going to work for me. There are so many people who are going to be better at it because it’s what they do. It’s not my strength, but I just got caught up in responding to the moment.

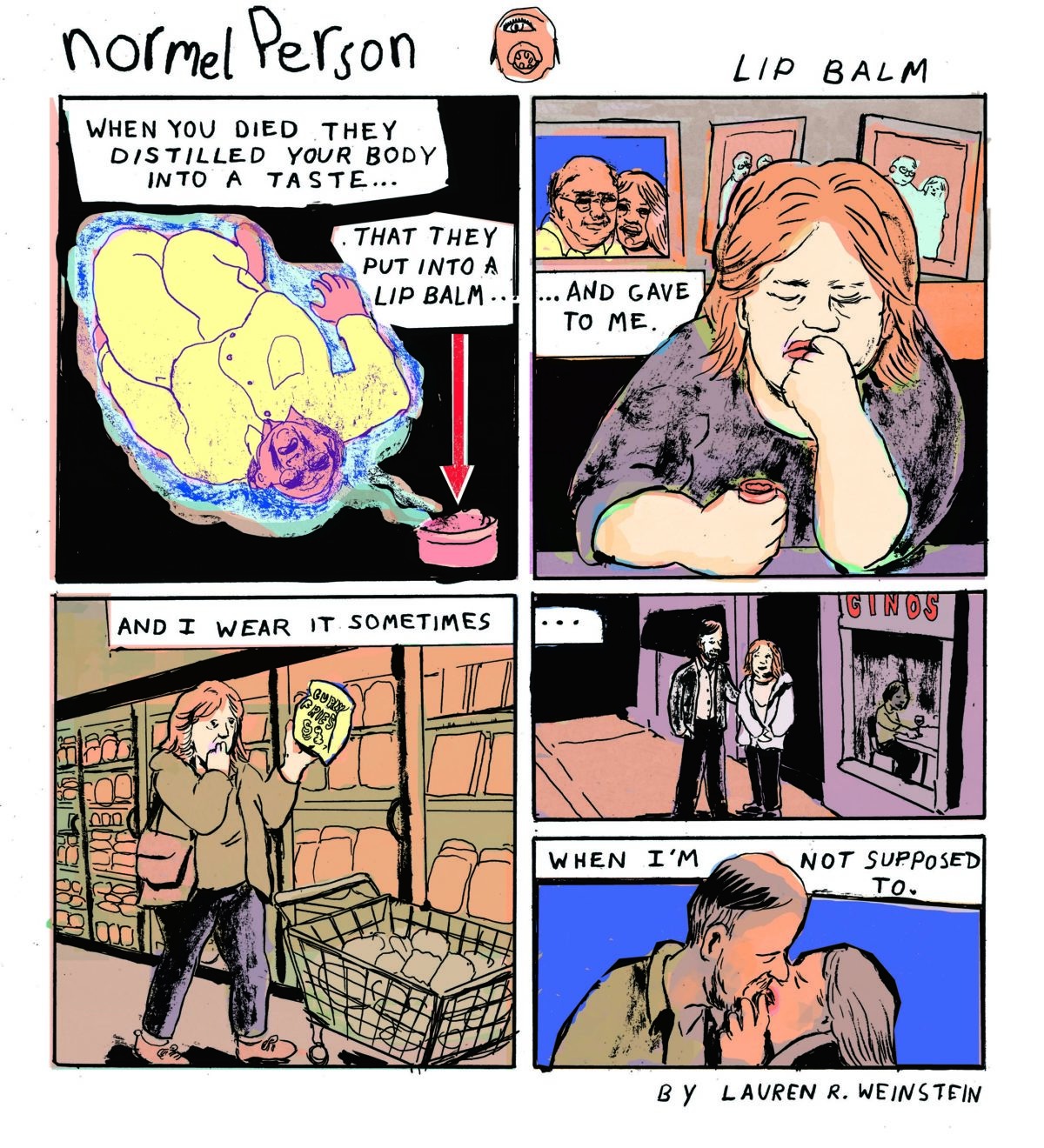

My very favorite “normel person” comic is actually the one [published December 8, 2016] titled “Lip Balm.” It was one of the first comics I made for the strip, and the Voice did not want to print it. They said it was “advertising poison” because it’s so weird and dark and not sexy. It wasn’t commenting on anything in particular. It’s just a situation where this dead man is converted into a lip balm that his widow likes to put on her lips to remember him. And then she’s dating somebody else, but she still has the lip balm on.

It’s the weirdest. But somehow, it touches on a mood, and it feels like a whole short story told in four panels.

BLVR: The strip was always composed from a square either making up one big drawing or divided into four-panels. How did you decide on that format, and what was the rest of weekly process like, from coming up with ideas to publishing?

LW: That was the space given to me by the Voice for their printed page. It was just short enough to be succinct, but I could also do a lot within it.

The process of making the strip involved lots of procrastination on my part, but there would also be a delay in printing. Each week, I would file on Monday and the comics would come out on Wednesday. By that time, the news cycle had already completely changed.

I would have three or so ideas floating in my head, and I’d have to pick one by the Wednesday before. A big part of a weekly is just committing to an idea. I found a lot of revision happened right on the page.

I worked with two editors at various points. Really, they were just trying to keep their jobs because the Voice was owned by this person who had no real vision. He had bought it because he thought it was a good brand. Like so many weeklies, there’s no model for how to keep them running.

But I loved the process of making the weekly, which was freeing because it was all about the structure of it. It’s a little scary not having it now.

BLVR: Did you get a lot of audience response or feedback to your strip, which was coming out in print for the first year or so?

LW: By the end, I did feel like I had a fanbase. I saw things getting passed around online. People would take pictures of the strip printed in the paper and then put them up on Twitter or Instagram. I think for a while people responded to the strip because it helped them through tumultuous times. A lot of people told me, “I feel this too.”

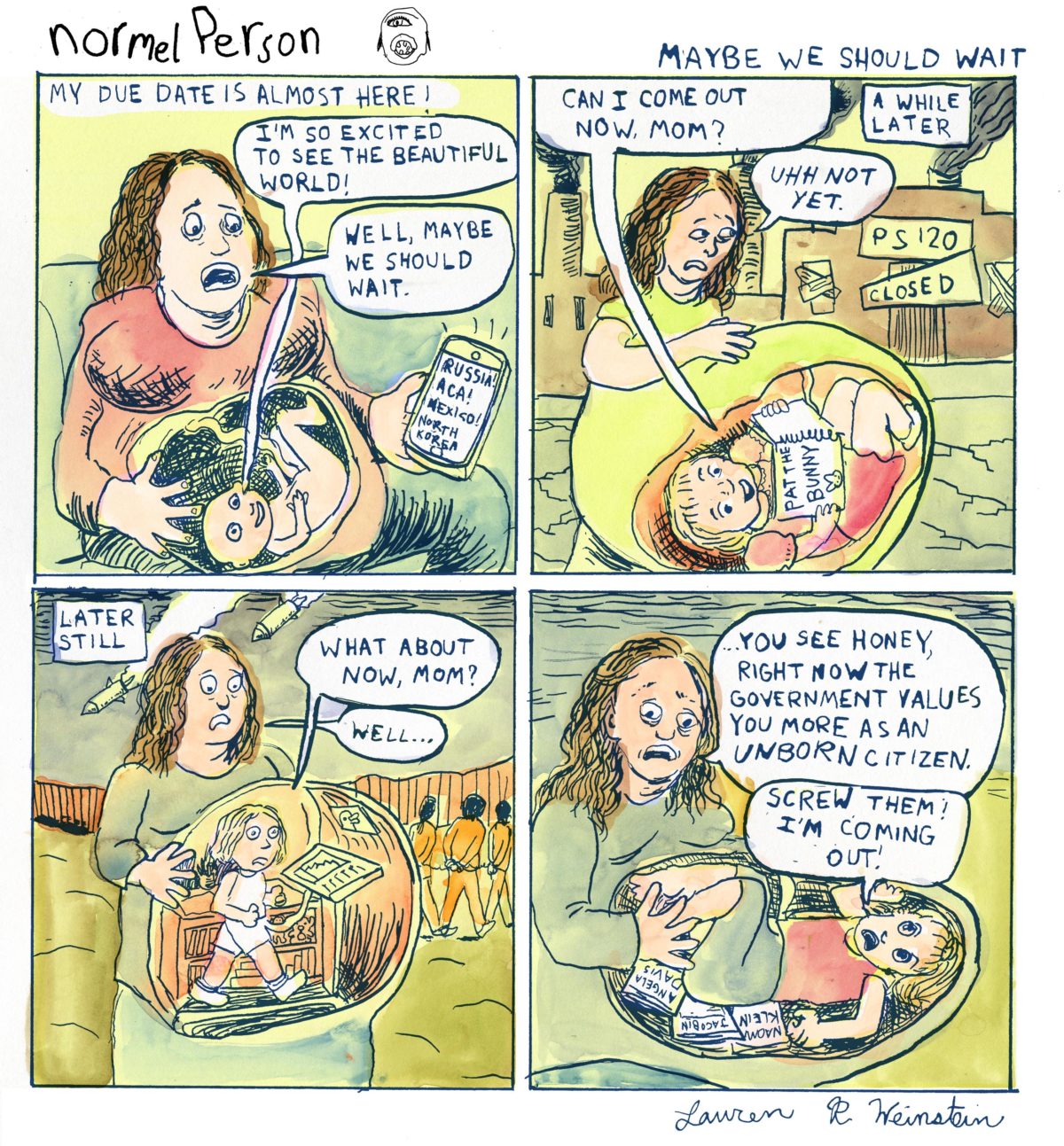

There was this one piece I did [published February 22, 2017] where, in four panels, I drew Sylvia stuck in my belly. In each panel, time was passing, and I was saying something like, “maybe we should wait to have you until after this new thing passes.” That was an example of making something absurdist about something real.

II. “Making work about the experience of being a mother needs to be elevated to high art.”

BLVR: Were you able to work on other projects while you were working for the Voice?

LW: Not exactly. I thought it would be something where I could turn over the strip in one day and then work on other stuff. But it’s not really like that. Because the most important, pressing deadline is on the strip; it becomes the thing that’s tweaking in your head all week. I’m excited now to tell longer stories.

BLVR: Some of my favorite pieces from the strip address the political via the autobiographical in a way that is somehow both direct and oblique, like a comic you did on #metoo, published October 17, 2017. In that one, you describe being physically (but not sexually) assaulted and fighting back, but you don’t actually address your own #metoo story, except to refer to a lesson you would “learn… later.” Similarly, you have a longer comic, published January 30, 2018 and titled “It Takes a Child to Raise a Village,” in which you also braid together your personal narrative with the current political climate in an unusual way. In that piece, you depict going to the Women’s March with your eight-year-old daughter. Could you talk more about this push-and-pull between autobiography and current events?

LW: I felt like when Trump was elected, we were all just living through history. I still feel like that. We’re done with even being funny about it. Everyone is just exhausted.

Writing about these big historical moments and how they affect me on a personal level was a way of giving them more of a shelf life. The piece about Ramona’s first march is about coming-of-age and not trying to tell your kids what to think, rather having them think things through for themselves. That’s the bigger story.

Days after the march, Ramona was still making up posters with slogans that she might have brought to it. And days after that, she was still talking about it, while in the bathtub washing her younger sister’s hair. I was watching all of this—the story that was being played out before me in this broader historical context.

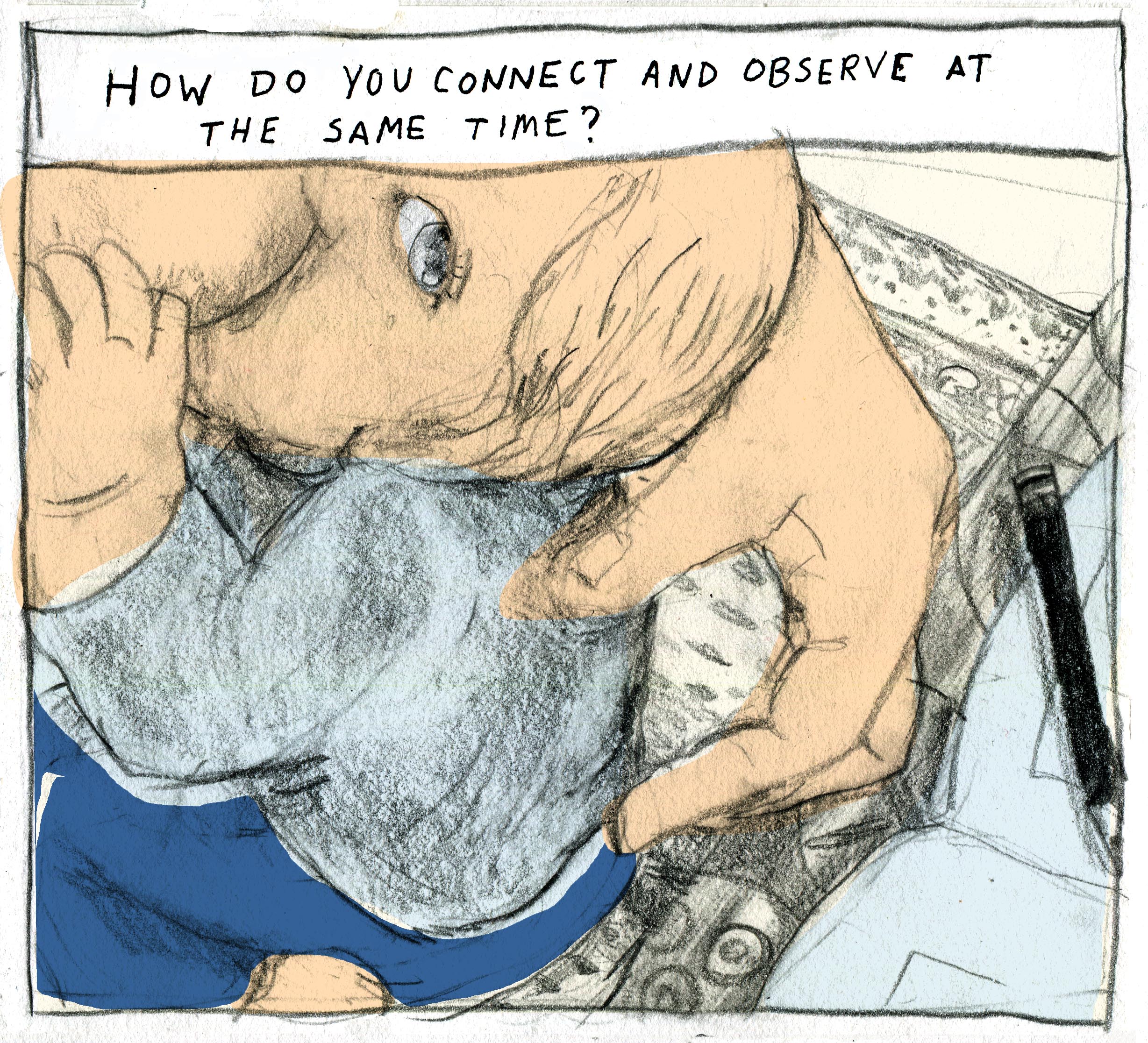

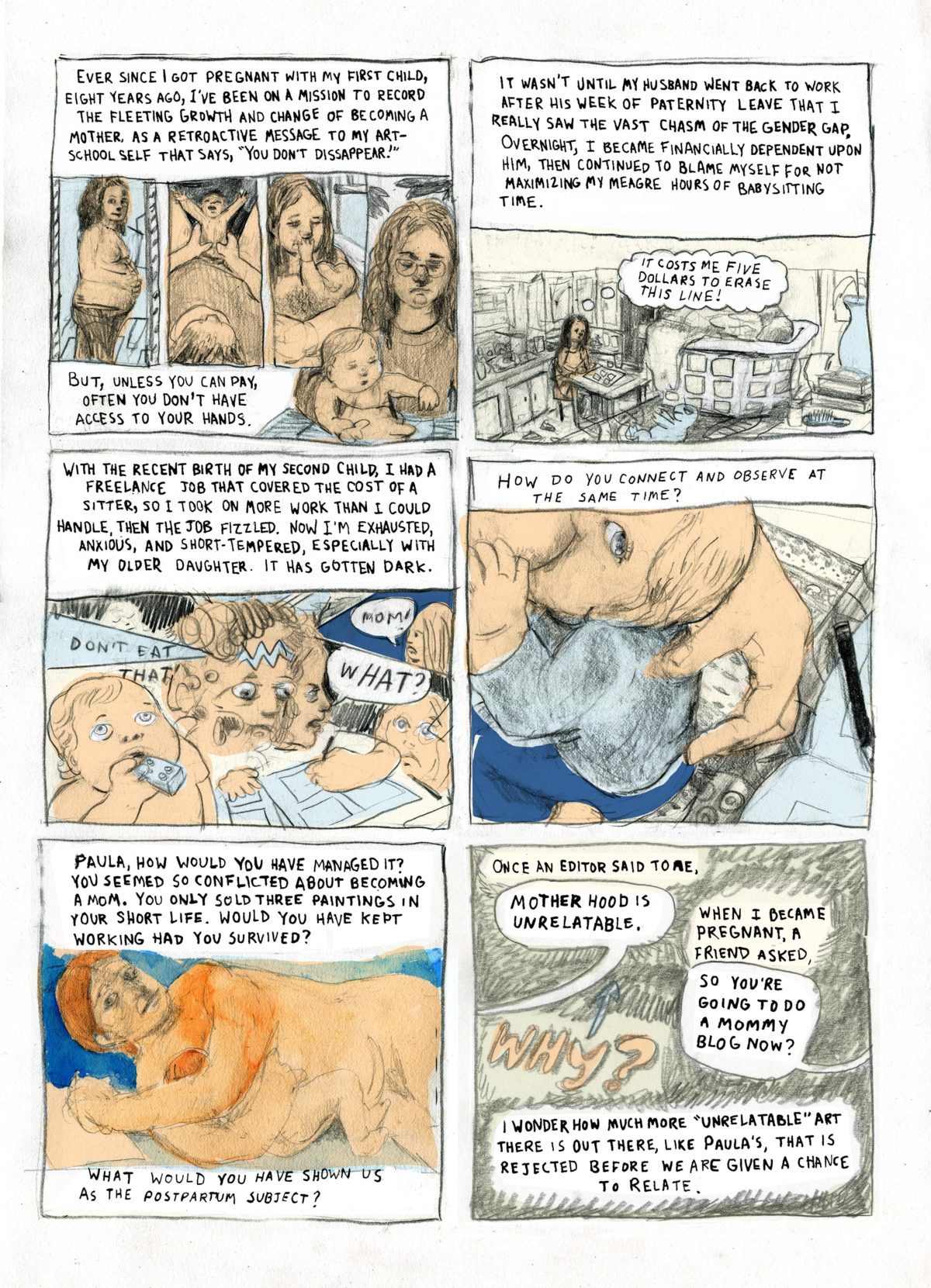

BLVR: In April 2017, the Voice went online, and a little over a year later it folded completely. You published a long comic in the “Culture Desk” column at the New Yorker just a few months later, on July 24, 2018. The piece, called “Being an Artist and a Mother,” is told in twenty-four panels and is based around a painting from 1906 by Paula Modersohn-Becker. It’s also a mix of genres—in this case, part biography, part autobiography. How did this story come about?

LW: One day, while I was lying there on my side with my little baby Sylvia, I saw this picture on Twitter of a woman also in a side-lying pose with her baby. It was the most beautiful picture I had ever seen, and I felt like it was a piece of art that should be known.

The piece was advertising an interview on The Paris Review site, by a biographer of the artist, Marie Darrieussecq, who had just written a book called Being Here Is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker. A friend of mine, who worked at The Paris Review, told me she had a galley. She also emailed me with a press release from the MoMA, about how they were finally hanging up this one painting of the artist’s. All of these pieces came into play, but at that point I still didn’t realize that I had a catalogue of Medersohn-Becker’s sitting in my basement, or that I had ever seen her work before. Had I blanked out her work because it had so much to do with mothers and children?

The piece wrote itself from there. Reading Darrieussecq’s book [translated into English by Penny Hueston], I found that she had a similar experience seeing the same painting. It made me think about how much other work is out there but never seen or catalogued. It’s funny because lately I’m seeing all of these shows advertised—which I haven’t been able to go to because of my new baby—but that seem to be along these same lines. Artists who haven’t been put into the canon for whatever reason, museums that are now trying to show that work. Like Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim, or Charles White at the MoMA. All of these people are posthumously being added to the canon.

The cool thing about the New Yorker piece is that people felt seen. It got linked on this Instagram site called @tribedemama, and there were so many comments that brought me to tears, like “I’m a struggling artist, I’m a mom…” Also, an art historian got in touch with me; and this woman named Carmen Winant had a show at the MoMA at the same time [titled My Birth, 2018]. It was made up of this hallway that you could walk through papered with photos, including pictures of her mom giving birth and other photos of births throughout the ages.

It seems like there’s a moment now where people are trying to take motherhood and being an artist seriously. Because I really think there’s nothing in place to keep women on as artists, or freelancers, once they have kids. It’s an incredibly difficult place to be. And doing work about it is also so maligned; the idea of being a mother is instantly discredited by everybody. Making work about the experience of being a mother needs to be elevated to high art.

BLVR: This New Yorker piece grapples with a number of issues related to motherhood and art, all at once. First, there’s the time and money element, the material circumstances of being creative while caring for a child. Second, there’s the problem of reception, or dealing with how other people react to representations of the experience of mothering. Third is the element that combines a bit of the first two, as when you include this central, probing question: “How do you connect and observe at the same time?” It’s almost as though the work of mothering gets internalized as somehow oppositional to the work of observing and creating—and maybe in some ways it is?

LW: Being a mother often means being there, being in that present moment. That’s what kids make you do. Creatively, that can be really exciting. You’re doing things that are non-verbal. You’re crawling around on the floor. Sylvia saw a menorah the other day, the way the lines were curved, and she said, “rainbow.” Because it is an upside-down rainbow. I find those connections wonderful.

But as an artist you also want to detach yourself. You want to have that one step where you’re away, and you’re recording everything. And I find that, even without all the other constructs, you’re always straining between those two things. The trick is having your own space. The trick is having a moment to yourself, which a lot of moms don’t get.

I just had a wonderful vacation doing no art at all and now I have that worrying thing in the back of my head where I need my own time and space to sort out my thoughts, just to disentangle everything. That’s what the Village strip did. It gave me an outlet to put everything down, whatever it was, and disentangle my brain. Now I have all these disparate thoughts, and I’m having trouble figuring out where they go.

Working [with the Voice] gave me a steady paycheck; they paid $500 for a weekly strip. Having a kid, you’re always weighing time and money. Now that that’s not a sure thing, things are more precarious. It’s interesting how that also affects the creative mind.

III. Sex and Shitting

BLVR: Your 32-page comic, “Mother’s Walk,” which was published in Frontier #17 in September of 2018 is another in which you explore this tension between living through an experience and recording it. In this case, you zoomed in on your second pregnancy and childbirth. Could you say a bit more about how this piece emerged, and what you were trying to do with it?

LW: Ryan Sands from [the publisher] Youth in Decline approached me about doing Frontier, which is his anthology of different artists. The people that had done Frontier before were my favorite cartoonists, like Eleanor Davis and Jillian Tamaki and Michael DeForge. They all knocked it out of the park with their stories, so I wanted to do that too.

The story I wanted to tell was of giving birth to Sylvia. I knew it was kind of outrageous to spend 32-pages just on the physical act of giving birth, but I didn’t know if anyone had tried it before. I had other stories to tell too. My dog died around the same time I gave birth, and it felt like this complete cosmic changeover.

BLVR: The book opens with your first doctor’s appointment—you only discovered you were pregnant with your second daughter three months in—and it ends with your two girls, the younger one now a toddler, sitting together in front of a window. Your older daughter is giving her little sister her first cider donut. How would you describe the piece?

LW: The way I like to think of it is as a short story. It’s mainly about two sisters, Ramona and Sylvia, finding each other. But I didn’t realize that was what the story was going to be about until I set about writing it.

It’s also about being a parent as well as a self-absorbed artist, and being able to create another character, who is your daughter, and seeing her outside yourself.

One of the issues I kept coming up against in making the comic is that having a baby is such a personal thing. I knew going into it I was so lucky. I had a textbook, natural birth; it was a fantastic situation. I was worried that I would alienate a lot of women because of this. I knew all I could do was focus on my experience and hope that translates to other people.

BLVR: In “Mother’s Walk,” you incorporate little bits of other women’s experiences alongside your own. On one page, when your friend Rami visits you in the hospital after you’ve given birth, you include two panels depicting scenes from her past, including a snapshot of a nurse telling her, “Don’t cry like a white woman,” when she was having trouble breastfeeding after a C-section.

LW: I had done some comics journalism before, for Nautilus. I interviewed caregivers dealing with Alzheimer’s and caregiving stress.

Rami was a friend who had a very different birth experience. I was shy about interviewing her because she’s my friend, and I didn’t know how much she’d want published. There’s a racial component, because she’s African-American, and I wanted to be sensitive to the differences in our treatment, but not make them like caricatures. At the time I was reading about mortality rates of African-American women versus Caucasian women in New York birthing maternity wards.

I was aware of all this, and I wasn’t exactly sure how to put it in there. So I kept it specific. The details of Rami’s story are what make it interesting. I found that being a brave interviewer really helped the story, and I hope to never forget that when interviewing others for future projects.

BLVR: Your Frontier piece has so many personal details, not just about yourself and your friend’s experiences but also with regards to your husband. You depict—pretty graphically—the two of you having sex to induce labor, and the parts that you both play throughout the birthing experience. How did you navigate writing about him, and why did you feel it was important to bring in that component?

LW: I feel like there is so much that’s taboo about giving birth. All of it has to do with sex—how can you not talk about giving birth without talking about sex, and shitting?

The way I depicted the sex in the beginning, it’s not sexy. Maybe it would be different if it were.

We were having trouble in our marriage at the time, and I talk about all that stuff. I felt like it was important for the story. To show everything with all of its texture, and not try to gloss over things.

Tim gets that what I’m doing is one step removed; it’s art. It’s just art you can’t ever show your parents… Although my parents did read it and sent copies to all their friends.

BLVR: Did you have a similar sentiment when writing about your kids?

LW: I don’t feel like I can write about Ramona anymore. She’s nine now, and she’s her own person. The piece about the Women’s March is the last one I’ll ever do about her that’s not in the past, looking back on things.

Coming to the end of where I feel comfortable writing about Ramona is another reason why I’m going back to this longer memoir about my teenage years that I’ve been working on. There’s plenty of stuff to mine there, and I don’t feel like I can write much more about the present world with her.

IV. “The Ghost in the Nursery”

BLVR: Could you talk a bit more about this current project?

LW: The book is called Calamity. It starts with a story about how I became an atheist during my bat mitzvah. Writing the book now has been helping me understand where my mom, who has worked doggedly trying to provide social services to poor people, was coming from, since I’m also now a mom.

But here’s a problem with it: spending all day thinking about myself as a teenager is putting me in this reckless childhood world. And I’m finding that then having to switch gears back into parenting mode is difficult. I’m trying to be receptive to the person that I was as a teenager, without revising it—though I can’t help but revise it.

BLVR: Do you feel like having a nine-year-old now and writing about yourself as a young adult changes your perception of the past? It seems like parenting can be a great opportunity for self-exploration, but it’s not often acknowledged as such because your attention is always supposed to be on the child.

LW: There are certain things I can’t help thinking about as I write the story. For example, Ramona recently decided she wants to be Jewish. At the same time, I’m writing a story about how alienated I felt getting ready for my bat mitzvah, and how it introduced me to what it means to be an artist. Ramona is giving me the chance to revisit Judiasm through her eyes, but as a writer, I have to stay true to my thoughts back then. How much of my personal development do I allow back into the story?

There’s a comic I want to do about parenting. I read this piece about something the author referred to as “the ghost in the nursery.” Where you’re parenting, you and your child are in the room but there’s also the ghost of parenting past: how you were parented. I love the metaphor of the ghost in the nursery, and I think about it all the time. When I’m with one of my kids, I wonder, how much is this me projecting something on her, and how much is this just her being her?

I remember sitting with [my husband] Tim, right after we had Ramona. We were in Colorado for a big family gathering and my parents sat me down and told me three insane bits of family history that I’d never heard. It was like, once I had kids I was allowed into this place that I could never go to before because now I was part of this continuum. I think about that all the time. Parenting and time, cartooning and time. In cartooning, you’re always playing with time. It’s something I’ve always been obsessed with and now it gets played out every day. It’s like I’m living two timelines at once. The cartooning becomes a way of holding on, because time is so fleeting.