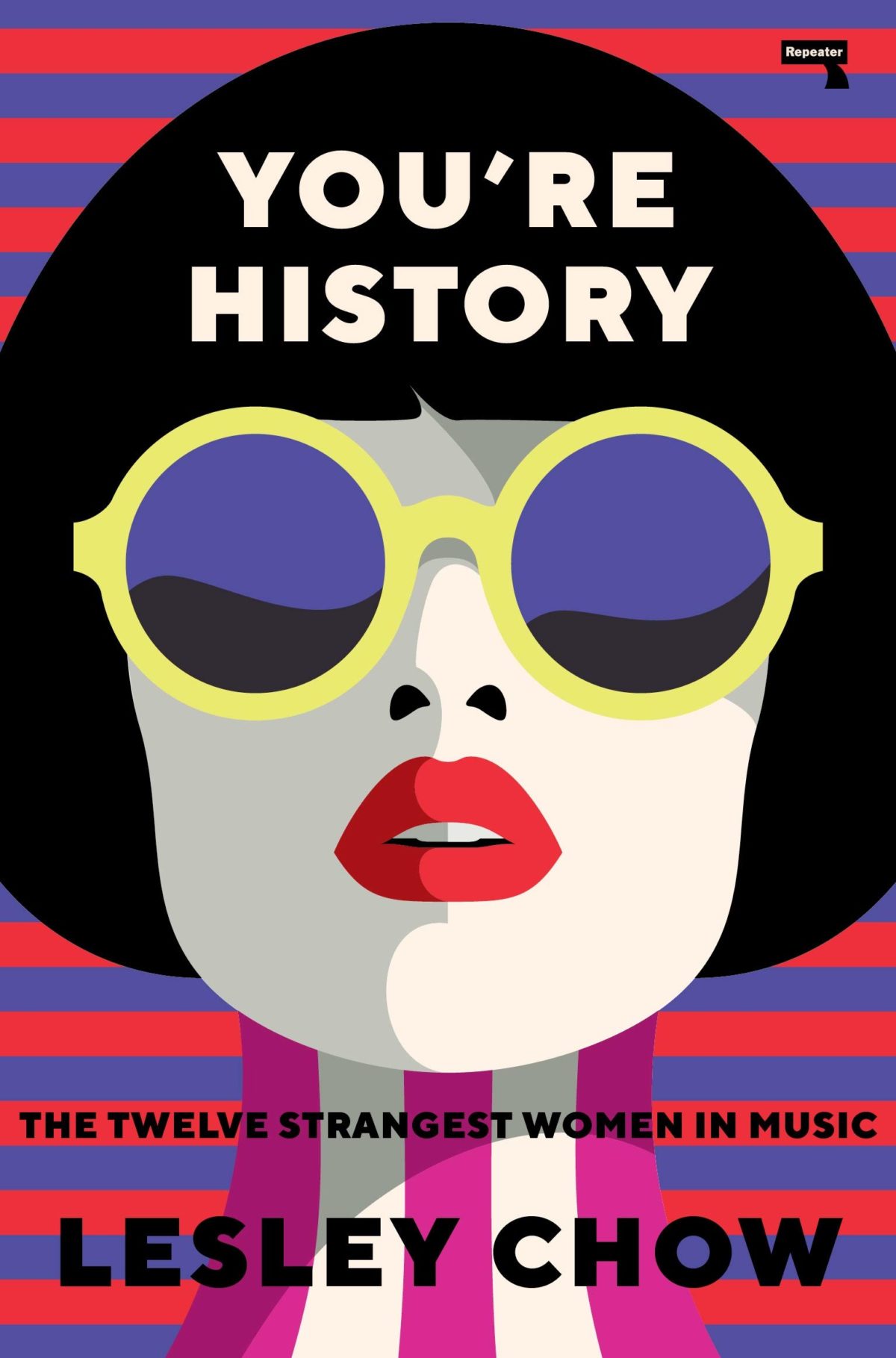

Lesley Chow likes to keep things interesting. An Australian critic, she started her career in film, focusing on soundtracks. Since then she has moved from film to music and back, uprooting herself before she gets too comfortable in either mode. This spring, she published You’re History: the 12 Strangest Women in Music, a kaleidoscopic essay collection six years in the making that highlights some of the most uncanny women in pop music from Chaka Khan to Azealia Banks. Throughout the collection, Chow’s passion for strangeness, for “the feminine sleaze” as she puts it, blazes through. Just as the women she heralds refuse to prune or polish themselves, she dismisses self-serious titans of lyricism in favor of the ecstatic “ooh” of disco or a single tic of Neneh Cherry’s voice with an infectious, wry glee.

Chow’s laser focus on the texture of a song beyond its lyrical value (or lack thereof) is a revelation. Nothing is left uninvestigated; timbre, rhythm, emphasis, even the shape of the singer’s mouth are subjects of fascination and discovery. The mystery of a perfect pop song, how and why it hits exactly right, is something she strives to capture even as she acknowledges and celebrates its undefinability.

Chow and I talked over Zoom on a sticky evening in Las Vegas and a bright afternoon in Melbourne, the “most locked down city in the world” as she described it. Talking to her, I was so impressed by her staggering, encyclopedic knowledge of pop music and film alike—the mark of someone truly obsessed with their work. She even sang a few of the lines she was referencing for me, though I swore I would never let anyone else hear the recording. You’ll have to take my word for it.

—Haley Patail

THE BELIEVER: I’ve been dying to know what you think about Taylor Swift’s newest incarnation. What do you think about the Folklore era?

LESLEY CHOW: I personally like Taylor when she has that kind of nasty glamor to her. And with this incarnation, I think there’s been some good songs on the album but it doesn’t excite me as much from a pop point of view or… The music is more tasteful than I personally tend to enjoy.

BLVR: [Laughs] Too tasteful.

LC: Yeah! I like there to be some sharpness, some abrasiveness… something puerile, that’s what I like.

BLVR: Yeah, she doesn’t seem to have a lot of fight in her this go-round, she’s not like throwing punches. She’s sort of just wearing big cardigans…

LC: Yes, but I hope that we’ll see that kind of femme fatale persona again, and maybe some of the toxic persona as well. [Laughs] Well, that’s what I like in pop, in Taylor Swift or anyone else. I like it in Shakespears Sister, I like it in Neneh Cherry, even in Azealia Banks, you know, and not everyone does.

BLVR: Is there anybody new on the scene that you think has toxic potential?

LC: Not so much, everyone is so guarded and afraid of being cancelled. Everyone is so media trained and has these kind of pithy comments for Twitter. It’s hard to catch someone off guard in that way and it’s hard for people to be unguarded in their music, I think.

BLVR: Totally. And do you feel like it’s always in retrospect… like, I was thinking about this a lot while reading your book, is it only possible to have this viewpoint after it’s over? And you can look at it without whatever the artist is saying in the media at the time or their persona when they’re releasing the album?

LC: As in, is it only possible to see the strangeness in their music, do you mean?

BLVR: Yeah.

LC: Well I think it’s possible at the time. I mean, the first time you heard Neneh Cherry’s “Buffalo Stance” or Azealia Bank’s “212” it really snapped you to attention. There’s nothing else like this. And you’re sort of driven to digest that before any part of their media persona, I think. And if a track was to come along that would arrest our attention in that way, I think it would be the same. But it’s been a long time since… I mean it’s been almost a decade since “212,” so.

BLVR: Do you think people are just afraid of being abrasive?

LC: I think that the current need to be very self-conscious and media savvy, to be very self-aware in terms of your position in the culture, isn’t necessarily conducive to producing something truly innovative. I don’t know if that’s a cause, but it doesn’t encourage it.

BLVR: Sure. And do you think Twitter… I feel like Twitter is a pretty caustic place, like, there are parts of it that are very hateful…

LC: But it’s more snark.

BLVR: Yeah, okay.

LC: Snark is a very socialized kind of strangeness or quirkiness. You don’t get that feeling of, “where did that come from? Who is this?” Most witty people on Twitter sound like the same person, it sounds like the same person could really have ventriloquized all the parts.

BLVR: That’s so true, or it’s the same joke told with like a slightly different wording.

LC: Well, it’s like learning a new language, like learning the different tenses…

BLVR: Interesting, I hadn’t thought about that before. Yeah, I guess I was just thinking a lot about how much you honor what’s strange and I wonder if, like you’re saying, sometimes you can tell right away because it doesn’t sound like anything that’s ever happened before. But do you ever find that sometimes it takes you a while? And then you’re like, “actually, this is really strange.” And it stays with you and becomes stranger over time?

LC: I think that’s true. And I think that’s a difficult thing. Strangeness is a difficult thing for music criticism to deal with because historically it’s always been more topical than, say, writing on film or literature. There’s always this tradition of covering and summarizing all the week’s new releases and being able to pin down all the references and genres in a track. So probably the temptation is to write on a song that you’re certain about, the one you can place rather than the one that puzzles you, the one that might take weeks or months or even years to decode. So I don’t think slow criticism is really encouraged in music writing. I write [about] film as well and there are so many publications like Senses of Cinema or Film Comment where a writer would take a key moment in a scene and break it down. But I’m not sure there’s as much tolerance for that kind of close analysis in music writing even though we do have sites like, you know, Albumism or Pitchfork that do look at past albums in detail. I think that might be seen as pedantic or it’s just not really valued.

BLVR: Yeah, and it’s strange that it would be seen as more pretentious to do a close reading of a song than a movie when a song could be with you so much more in your life than a movie. If you watch a movie once it’s like okay, that’s like three hours and now it’s done. But you could easily listen to a song hundreds of times and really get into every second of it, and examine every single sound.

LC: But in general, yeah, I think [the music criticism publishing schedule] doesn’t really allow for that kind of deadline.

BLVR: Right

LC: It doesn’t have those long ledes where you can really get into a song as opposed to summarizing its intentions and where you think it might be going.

BLVR: Right. And it’s more of a risk to say “I don’t know why this song makes me feel this way.”

LC: Absolutely. I think unknowingness is something that… For instance, like, you know “the Think Break,” that like “woo yeah” that samples James Brown? That’s probably one of the most haunting sounds in pop and it’s been used literally on thousands of tracks, tens of thousands of tracks, maybe, from TLC to Madonna, Big Audio Dynamite. And somehow it always works, it’s always really alarming, it’s always really compelling. But I’m not sure anyone’s gotten to the bottom of it, you know. Why is that particular sound so irreplaceable? It’s the foundation of so many tracks, not only in dance but in rock. It would be rare to hear anyone try to get to the bottom of a sound like that, even though it’s so foundational.

BLVR: Yeah! It’s almost like it needs to be examined from more angles than just description. I often find the use of adjectives in a music review to be really… they’re not helpful, I don’t find them to be helpful at all because I’m gonna hear it when I hear it and the sounds will conjure what they conjure for me. I think you’re the only person I’ve ever read who’s just talking about the sounds and what the landscape of the song is. It’s almost linguistic rather than literary, you’re looking at the actual tones.

LC: I mean it’s kind of a paradox in a way, right, because on the one hand I’m saying these effects can only be conveyed through music or only through film, but then I’m also trying to look for language to try and describe its effect. I’m basically refusing to look away or stop listening until that language is found. So, I’m sort of pointing this way and saying these can only be conveyed through sound but I’m still gonna have a go and try and explain what I think is hypnotic about it.

BLVR: It’s valiant. And I do think that for someone who didn’t hear it the first time, if you point it out for them, then they might be able to access another level of the song that they aren’t even listening to. Like I feel like I for the longest time listened to the lyrics first, because I’m a writer I think, so I just wanted to know what the words were, but talking to my friends who are musicians, they hear the song in a completely other level. And that’s so hard if you have to write a review the week before the album comes out, like you might not have time to sit with it long enough to hear everything that’s even there.

LC: Right. I mean, if you’re thinking about slow dawning strangeness, I mean, how about the voice of Rihanna? It’s pretty bizarre. People talk about it as a weak voice or a limited voice and… To me it’s kind of like listening to the voice of Isabelle Huppert or something, you sort of listen to it again and again, and it has this sort of specific flatness or deadness to it that is somehow really appealing and really versatile. So I mean, that’s probably one of the most challenging things to try and do… one of the most fun and challenging things to do as a critic is to try and decode that kind of strangeness and try to work out why that sound or that image has this specific hold on you. I think I’m drawn to writing about sounds that have puzzled me for years. So, it’s been a time of trying to work out, “why does that sound bring up these sorts of textures? Why is it so specifically tinny or tarnished?” So I think I’m looking for enduring strangeness. That’s what I’m drawn to writing, anyway.

BLVR: I was thinking a lot about the “head” vs “body” music divide that you’re talking about in the book and it rings very, very true and I think it has to do with this other thing you’re talking about which is the things teen girls love, which is pop, most of the time it’s new pop that no one else is listening to, and they get a lot of flack for that until someone who isn’t a teen girl listens to it and is like, “oh, actually, this is good.”

LC: Right, yeah

BLVR: But it seems to me like those two things are really, really linked. Because the teen girl body is the source of so much shame and outside derision. So what a teen girl body loves is not being taken seriously on compounded levels. And I wonder about your experience as a teen music listener. Did you feel those systems happening to you or were you not swayed?

LC: Well, I’ve never been overcome by, you know, Beatlemania or One Direction-mania or anything like that, unfortunately, because I would love to be in the midst of that whirlpool. But I’d probably say that what’s the most exciting to me is the loss of self and total immersion in sound. Like whether it’s Chaka Khan’s voice or the palpitations of disco, which is another genre that’s not terribly respected. So, where you know, some critics might value that really knowing voice of bitter cynicism in rock and in music generally, what I like is sort of involuntary movement, unquestioned movement in the hips and in the body, so that you’re listening to it in the heat of the moment rather than with this sort of cool detachment and this sort of refined appreciation. And the problem is that this kind of “body’ music is hard to quantify, it’s hard to grasp in any kind of literate way. Because you sort of have to pull the words apart into syllables and what they’re doing at any given time. It’s so much more about the way someone sings a line than the line itself.

BLVR: Right! Yeah, I was so struck by you talking about the singer’s mouth, and how a song could make your lips move. It’s so strange that I’ve never heard anyone else talk about how singers have bodies! A singer is a voice in a body, it’s not just this voice that’s like stuck in the track but it doesn’t exist anywhere else. The physical reality of music is something people don’t talk about when they’re critiquing a song or an album.

LC: And the way that some of the singers in this book, particularly I think Chaka Khan and Sade, make words into delicious morsels, they can’t really be analyzed in terms of literal meaning in that way. You know, Sade loves to talk about like “coast to coast” you know, “Chicago”, “Key Largo” you know and probably to some people it sounds like a very jet-set song. But you know she just loves to stroke these words again and again.

BLVR: Yeah! It’s weird to me that it wouldn’t be so obvious for other critics to think about the physical reality of singing. And how it also relates to this idea of unpredictability or surprise, that the best part of a song could be someone’s voice cracking when they’re singing it.

LC: Yes!

BLVR: And that’s where the magic is, not in what’s written down on a sheet of lyrics.

LC: Right, because I don’t think she’s necessarily thinking, you know, I’m just going to deliberately coddle every “c” sound in this song. It’s just that her voice is drawn to doing that.

BLVR: I really want to talk about one-hit wonders! I love that you say that pop “boasts” the most one-hit wonders of any genre and I just wanna know why you think we should be celebrating one-hit wonders.

LC: Yeah, well, you know, one-hit wonders are sort of generally considered to be the domain of pop rather than an enduring career in rock, and they tend to be mocked rather than celebrated. But I tend to be really interested in one-hit wonders, whether it’s Betty Boo or t.a.T.u.,cause there’s that mystery of the particular combination of sounds and textures that simply works and hits. And why is it that combination that struck a chord with the public and no other? Just once and never again? But unfortunately one-hit wonders are increasingly rare these days because the industry actually works to prevent them. If no one really makes money from music anymore, then it’s more about building up a star’s brand and trading off of that and that means consistency rather than quirks and outliers. So, if a record company comes across a potential hit song from someone who hasn’t had a hit before they’ll probably remove it from that person and give it to someone who’s considered, you know, the whole package, or visually marketable. So, in doing so, that song will usually be removed of its idiosyncrasies so that it can be sung by a star.

BLVR: Right, and fit into their album, and not be a stand-out track.

LC: Exactly. So, you know, these days a song that becomes a hit without a master plan or being hyped to death weeks beforehand is quite unusual. I mean even a song like “Boo’d Up” by Ella Mai that comes up the charts gradually just because people like it, I mean, that’s incredibly rare. It’s really lowkey, it’s not the kind of song that you win American Idol with because it doesn’t go anywhere. And I don’t think there’s much time today for songs that don’t go anywhere. What are they for? We’re not allowed to have one-hit wonders today because they don’t make commercial sense and I think music is really the poorer for it.

BLVR: And do you think it has to do with the way music is consumed, and how that landscape is changing? Like it’s maybe not so likely that you hear a song on the radio and go “wow, I really liked that” and you don’t even know who sung it, you just know you really liked it and you wait for it to come on again.

LC: Right. You’re not coming across tracks in the same way. It’s more about being presented with something that’s already been hyped and working out your own reaction to it. But the magic of pop is that it has so many one-hit wonders. It’s so unusual to have a one-hit painter or director who just hits just one and then that’s it. So, I mean, I think the genius of pop music is that it doesn’t necessarily come from, you know, very hard thinking about lyrics or sort of mapping out ideas. It really is sort of about that flash in the pan that comes from having time to rehearse or play around in the studio. Not the current conditions under which music is produced now.

BLVR: Yeah. I feel like even commercials have changed. I think a lot about those really early Apple commercials for the iPod where the entire commercial was just listening to a cool song. Like that was the whole point of it! And that doesn’t exist anymore.

LC: Right! The jingle is gone. Jingles are considered cheesy. But you know jingles are some of the most uncannily memorable tunes and phrases. That’s disappeared as well. That incidental magic of melody in pop that’s really sort of disappeared.

BLVR: Yeah, it’s like you were saying with Twitter, it’s the same grammar for all songs, like… even in like movie trailers. I feel like there used to be cool music in movie trailers and now it’s like that sound from Inception, that bass sound in every trailer!

LC: Yeah, exactly. Well, this works for people so let’s just put it in there again and again in the trailers, the same beats again. Um, I mean… You know that Prince song “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker” where they recorded it with a faulty console so it sounds really weird, it sounds like someone’s doing plumbing in the house while they were recording? It has this kind of really weird, flat, thin sound to it. But they didn’t want to interrupt Prince’s performance, so afterwards they said “record again” and he’s like “no, I’m attracted to that sound.” It’s unlike anything else in his work. That is really unlikely to make it to air these days.

BLVR: Yeah, right.

LC: Or, the song I discuss in the book, “I Feel For You” by Chaka Khan where the producer’s hand slipped on the machine while he’s working with the rap and it goes “chaka chaka khan, chaka chaka khan” and there’s this whole “chaka chaka” locomotive sound that propels the song. Something that’s addictive and unaccountable, I don’t often see that today. The alchemy of pop music.

BLVR: What a shame…. Yeah, I almost wonder if it has to do with albums…. Like I think a lot about the album and if I think it will survive Spotify’s reign of shuffling everything. But it’s almost like you’re saying, even on a song level, maybe the album is a destructive project for pop in particular because it’s eliminating the one amazing song in favor of an album that’s sort of lower level but more consistent, where every song sounds the same.

LC: Well, yeah, that’s the algorithm of Spotify, isn’t it? To pick songs that are not so much outliers? If you liked this, you’ll love that, you know?

BLVR: Are you a Spotify user? How do you listen to things?

LC: I do, just because it’s really convenient to listen to things or moments over and over, and I have no idea where most of the music in my house is. So, yeah, purely as a matter of convenience, yeah. But I’ve heard stories about how that Pavement song that even fans aren’t really familiar with has become the most played song because it represents maybe the median, the mean of all Pavement songs, it’s the most typical.

BLVR: The average Pavement song. [Laughs]

LC: Yeah, yeah. [Laughs]

BLVR: That sort of terrifies me. Because if that’s the only song you hear, and it’s the “average” one, you’ll think “oh, this is what they all are.”

LC: Right, right!

BLVR: But no, it’s really the least remarkable one!

LC: Maybe that’s an art, you know, it’s like easy listening programming. Find the most typical songs of their time or genre. [Laughs] Songs where nothing specific sticks out, where there’s nothing dated about them but at the same time there’s nothing strange about them.

BLVR: Right, well, the datedness is sometimes the best part. Like these older synths…

LC: Yes!

BLVR: They were just obsessed with the sound because it was new to them.

LC: Exactly! And so when you listen to Prince or Kate Bush you wouldn’t be like, oh, if only these could be updated with, you know, cleaner sounds or analog sounds. I mean, Kate Bush did do that with her sort of revisionist album Director’s Cut but I think the songs were much more interesting in their original incarnation. She was obsessed with the Fairlight, and there was all this kind of smoke and mirrors, it had that kind of… the sound of primitive magic to it.

BLVR: Yeah, right! Because there’s almost this encapsulated excitement in the song, of just hearing it. Because they were just excited to be playing it.

LC: It’s excitement, it’s almost a belief. You know, I don’t think it’s just nostalgia that has us looking back and finding those sounds charming.

BLVR: Yeah! Well it’s like you’re saying about disco in the book, that disco believes that the song can last forever, that you can just stay in that ecstatic place and it never has to end.

LC: Right, right. But when you listen to the modern versions of disco by Dua Lipa or Kylie Minogue, it’s very much about sampling the sound of those times but recognizing that we can only really afford one or two grooves per song. [Laughs] And we’re gonna have to stretch them out sparsely. And they’re gonna be effective but it’s not that promise of endlessness or futurism. It’s not that kind of excitement.

BLVR: Right, or like cacophony. Like it feels very… each thing has its place. Now there will be a groove, and then we’ll go back.

LC: Right, right. Curated is probably how it feels. Like, maybe tweezerfied. You know how food critics refer to dishes as tweezerfied because you’ve got this very sparse, elegant arrangement of little gels and little elements on a plate?

BLVR: Oh, sure.

LC: But at the same time your body doesn’t have the strong reaction of, I want to eat that. You’re sort of eating it as a mental exercise.

BLVR: Right, well. It’s very beautiful to look at but it doesn’t look delicious.

LC: Right, so what food critics call “tweezerfied,” that’s what I think of this kind of music, where it’s kind of carefully curated and arranged, beautifully, tastefully designed, sort of like a mood board.

BLVR: Right, I was gonna say it’s like Pinterest. A pinterest board of the 70s.

LC: Right. Yes!

BLVR: Like everything’s here but…

LC: But not… it doesn’t provoke any reaction from the body.

BLVR: Right, it’s like you were saying, the aesthetic of it. Like, “oh that guitar sounds like it could be from the 70s.”

LC: Yes, like, here’s what I would wear to Studio 54! That kind of thing as opposed to, this is what it would be like to be in the midst of that excitement.

BLVR: [Laughs] Right.

LC: More like style inspiration.

BLVR: Right, it’s staged. A pop-up, oh, this is 70s inspired, but it doesn’t have that drive.

LC: Mhmm.

BLVR: Which is so interesting because you’d think… I mean, whatever, nostalgia is an engine and it just keeps moving and now the 90s are nostalgic, but like I feel like the 70s are having a moment and you’d think it would include more of the, like, desperate social climate, this energy of being unhappy with the way the world is and wanting to sing a way for it to be different or create a world inside of your song that’s happier.

LC: No, it definitely feels like a superficial sampling of the elements of an era each time rather than the feeling behind them.

BLVR: IAre there other things you’ve been mulling over recently, since the book has come out? I know you worked on it for a long time. Are you ready now to work on something new, or are you still mulling it over?

LC: I think I’ll be ready once the press cycle is over, which has been fairly overwhelming. I think I’ll be ready to start working but I think my next book will be on film for that reason. I sort of like to bounce between the two so that each time I have to sort of find a new language or a new approach for describing what I’m looking at or listening to. So, I think that’ll be more challenging for me rather than sort of getting into a groove with either film writing or music reviewing. I’ll go back to film, which is where I started, and find it odd again to write about scenes and shots and maybe need to sort of adjust the language I use to describe those. And then come back to music again later!

BLVR: Do you spend a lot of time thinking about the way music is used in films? Or do you mostly stick to visual language when you’re thinking about film?

LC: I did start off writing about soundtracks, particularly in the work of Bertolucci, so I do think quite a lot about sound in films but I would say that soundtracks today sound, again, a lot more curated and have less to do with creating a total mood for a film. Especially now that Ennio Morricone, one of the last of the great composers who would absolutely draw you into the images, has gone.

BLVR: Yeah.

LC: It seems like more about, often, ironic use of music. Ironic use of a track that you’ve heard before. You know whether it’s the use of a 90’s girl power song, the sort of sarcastic use of that… Under the Skin had an extraordinary soundtrack I thought. The abrasion of the sound almost seemed to scrape the images on the screen, it was really that textural. But that’s quite unusual, I think.

BLVR: Yeah, I’m trying to think of some. I don’t know if you’re a Nine Inch Nails fan but I feel like sometimes Trent Reznor’s scores do that…

LC: Oh, yeah! Yeah, definitely, for sure! Especially in Gone Girl, I think, where I think part of the music was inspired by David Fincher going to a chiropractor or something and the soothing effect of the music, the sort of insincere,syrupy effect is what he was looking to reproduce in parts of the film. I think the use of sound in Gone Girl was fantastic.

Or Jonny Greenwood’s soundtrack for You Were Never Really Here. That was absolutely stunning. Really heartstopping, that’s one of the most brilliant soundtracks in years. You know, each beat seems to sort of drive you deeper into the film.

BLVR: Yeah! He’s done a few, it’s probably similar to Trent where he’s someone who is allowed to go wild, they don’t have to be pleasing anyone. It seems like also those are people whose soundtracks are almost omnipresent, like the entire film is underscored by this music. Rather than, like you were saying, ironically putting one song in to punctuate a moment. Having something that’s really fleshing out the entire sound of the film.

LC: If you have a soundtrack where it really plunges you deeper into the film and really immerses you into the film then that… why wouldn’t you have that? You Were Never Really Here, that’s probably the best example I can think of in the last decade or two. You know, Morricone with the Hateful Eight also. I mean, what a huge loss. Seeing that on the big screen. Almost the sort of parodically grand orchestration that he has. You know, normally orchestration isn’t funny, but it is with him, it’s almost sort of ludicrous, it spiralling out of control at times.

BLVR: Well, I hope that being in film mode is a breath of fresh air for you.

LC: I think it’ll be a little while before I get music out of my system because everyone wants to talk about music right now and “who are you listening to right now” and “who’s coming up that you would recommend” and… it’s gonna take me a while to get back to describing actors and scenes and shots again. It’s gonna be actually weird describing those things, and that’s probably a good thing. And not just a routine sort of film studies way of talking about them.

BLVR: Do you think that a level of discomfort like that is generative for you? To maybe not feel like you’re in the groove but rather you’re trying to figure out how to say what you wanna say?

LC: Sure, yeah. If I’m writing about something that’s very powerful, whether it’s music or film, and I think, “I might not be up to this, I might not be able to describe it,” that’s probably a good way to feel, that I’m almost struggling to get my head around it. Whereas, if you feel pretty sure how you feel about a song, how you would describe it, then I think that it’s going to be a less interesting piece.

BLVR: And you think maybe that’s something that’s in short supply.

LC: I was thinking that friends of mine who are weekly reviewers or writers, maybe some of them would rather wait for the object that really disorients them. And to be honest it would be hard for me to be a weekly reviewer because when it comes to a stunningly original track like “212” or “Buffalo Stance” that level of song comes across maybe once or twice a decade, especially since Prince died, so you know that really arresting song that stops you in your tracks and makes you focus on the strangeness of the sound. So… I’m not sure what I’d be writing about the rest of the time. [Laughs] That’s what I would be excited to write about and the rest of the time. Yeah. I don’t think I’d be pushing myself.

BLVR: Right. Well maybe it’s that the people who are assigning the deadlines are not like, “Okay, by this time next week, I want you to have discovered something that’s truly strange and inspires you.” They just want you to have something they can publish.

LC: Right. I mean maybe if they were allowed to go into the past and find great underrated movies or undiscovered tracks, maybe that could work. Butmost music that is produced is not really that interesting [Laughs]. Or most films, you know… I don’t know that most music demands to be written about.

BLVR: Yeah, I think that’s probably true. Are you choosy? Like do you listen to or watch a lot of things looking for that moment of strangeness?

LC: I’m definitely looking for that, I try to just listen to a lot of stuff and just put it on and just listen to everything maybe three or four times and see if anything comes up. I mean, in terms of writing the book, Róisín Murphy’s album which came out last year, if that had come out earlier that would have definitely been in the book because the textures of her voice are so interesting, especially as she’s gotten older. Her voice is clearly an aged and weathered voice, and obviously age today is the big taboo in music, much more than sexuality. So, to have someone not be a recognized icon like Patti Smith or Deborah Harry and yet have a voice that shows age and experience is quite unusual.

BLVR: Especially for women. Men are allowed to age.

LC: Images are airbrushed, but voices are airbrushed as well! A fifty year old doesn’t sound like a fifty year old.

BLVR: So you’re listening and waiting to be surprised?

LC: Yeah, I love to be surprised. I’ve been listening to some of the newer acts here in Australia: Genesis Owusu, his debut album just came out this year and he’s got some of the mercurial quality of Prince so he’s someone who’s super interesting. Tkay Maidza is another Australian artist who’s a shapeshifter and can shift between songs that are clearly designed to be hits on social media and songs that are more reflective. They’re both part of this growing African diaspora we’ve got in Australia that’s been very beneficial for the arts,. So… I think of other artists around today that are better known…. I think Tyler the Creator is probably actually the most intriguing. His songs are always structurally very unpredictable and ingenious. He’s someone I really want to look into more.

BLVR: Yeah, it’s hard in pop because I feel like you’re really banking on a chorus, or a hook of some kind. But it’s so fun to not get it, or to feel like it’s delayed, or somehow subverts the structure.

LC: Or for the hook to be something that’s incredibly compelling to your body, but you just can’t digest it at the time. Your mind can’t digest it at the time.

BLVR: Yeah. I feel like there’s something special about a song that you don’t stop for one second to think what it’s about because you’re just feeling it. And then someone will be like, “oh, why do you like that song, it’s about something violent,” and you’re like, “it hasn’t even made it to my brain, it’s only in my body.”

LC: The supposed subject of the song, I mean, if you listen to KLF and there’s that “e-i-e-i” sound that’s quite eerie and it’s like this widening and narrowing in front of you like a cobra— a sound like that, that is instantly naturalized by the body, that’s really unusual to come up with. Or some of the sounds of disco, you know, the “ooh” sounds or Boogie Wonderland where it’s like “ha! ha!” It’s an incredibly strange way to command people to dance, that sort of “ha! ha!” but somehow it works with the delirium of the song, it’s really inspired. I don’t know how they came up with that.

BLVR: [Laughs] Yeah like even breathing, the sound of people breathing, like a gasp or anything like that. So many songs they kind of airbrush that out.

LC: And Janet Jackson’s conventionally considered to have this weak voice, like it’s low, doesn’t have projection, doesn’t have the range of Mariah Carey or Whitney Houston, but it’s that kind of slightly asphyxiated sound that works so well, that slightly nervous sound she has when she projects. I love that about her voice. And that makes the supposed subject of her songs quite incidental.

BLVR: Yeah, right

LC: You were talking about people being like, “why are you listening to this song with this subject,” and the subject is almost surreal because you’re so absorbed in a particular part of the sound or the voice. Like if you think about that Salt N Pepa song “Let’s Talk About Sex.” The way they sing it, the keyword is not “talk” and it’s not “sex,” it’s “about”! “Let’s talk abooout sex,” it’s like there’s a whole world of detail and gossip in the word “about,” and “about” is the keyword. But if you were reviewing it, it would be hard to make it apparent that the song is about the word “about.”

BLVR: Right! It’s true, I love the word “surreal” for it, because if the bassline is telling you something totally different… You can say the song is “about” something else, but….

LC: Well for me it’s like when Lawrence Fishburne is in a film: he can be talking, and someone else is, in theory, speaking as well but I’m listening just to that bass. I’m listening to the sonority of his sound. I can’t concentrate on whatever exposition is supposed to be taking place.

BLVR: [Laughs]

LC: Or Viola Davis! You know: “how to get away with murder!” That voice! I don’t care about plot, I just want to hear Viola talking.

BLVR: [Laughs] That’s most of that show, I feel like…

LC: The best scenes are not the ones with other actors, the best scenes are Viola talking in front of a chalkboard! [Laughs]

BLVR: It’s more about the voice and the person than it is about the architecture around them.

LC: If my next book is about film I’ll be talking a lot about actors’ voices and the way that they can either draw you into a film or take you out of it. And why we don’t discuss that more. I mean everyone talks about Morgan Freeman’s voice or Cate Blanchett’s voice, that sort of, you know, grand Shakespearean voice, but there are other voices that are sort of weirdly attractive. Mark Wahlberg, I’d say, Diane Lane, Rebecca de Mornay. People who have this timbre that’s really unusual and really draws you into a film. It’s not really… it’s not a highly discussed aspect of film.

BLVR: But I feel like even subconsciously people pick up on it. Like, without even being someone who does impressions, there are some lines or speeches in film that everybody can hone in on and that’s a hallmark of that particular voice. The way it’s said is so easy to recall.

LC: Right.

BLVR: So Mark Wahlberg, okay.

LC: I don’t wanna be giving too much away. [Laughs] I have a lot to say about that but since this is being taped I’m just gonna you know keep it to myself for now. [Laughs]

BLVR: [Laughs] Okay, I’ll have to wait and find out. But I’m gonna think about it next time I see him. Did you ever watch Hail, Caesar!? I love the narration in that movie so much, it’s so funny.

LC: Yeah! Scarlett Johansson’s voice in that movie was really funny. I love her comedy accent—I don’t even know what accent she’s doing, like, it’s sort of like a dream of a Queens accent I think? That’s a purely movie accent that doesn’t exist in nature, but it’s no less compelling. Julianne Moore’s accent in The Big Lebowski, purely a movie creation. Or Judy Davis in Barton Fink. I don’t know why in Coen brothers’ movies women just seem drawn to putting on these odd voices but it works so well! Catherine Zeta Jones in Intolerable Cruelty. It comes from the language of movies, it comes from the tradition of screwball or noir.

BLVR: I know you are in the middle of this press cycle—are there things that you wish people were asking you about?

LC: People have been really quite thoughtful actually! It’s nice to be talking to someone who’s like a huge Neneh Cherry fan, like, thank god you’re talking about Neneh or Chaka Khan or whoever it is. I do get asked a lot why I didn’t include Laurie Anderson, why didn’t I include Siouxsie Sioux, and I think it was more interesting for me to find strangeness that was sitting right in the mainstream. The devil you do know rather than the one you don’t. The songs that you hear, probably have heard in Ubers and supermarkets and everywhere and yet somehow because they’re ubiquitous, they haven’t struck you as unusual. Those were the artists I was looking for more than the obviously avant garde people.