“I think my real talent is for being quick and impatient. I’m not someone who should be spending all her day doing something slow and painstaking.”

Situations on which Liana Finck’s Cartoons Have Commented:

The Fine Line Between Being Responsible and Overbearing

Hearing a Ghost Click a Pen

The Terror of Being

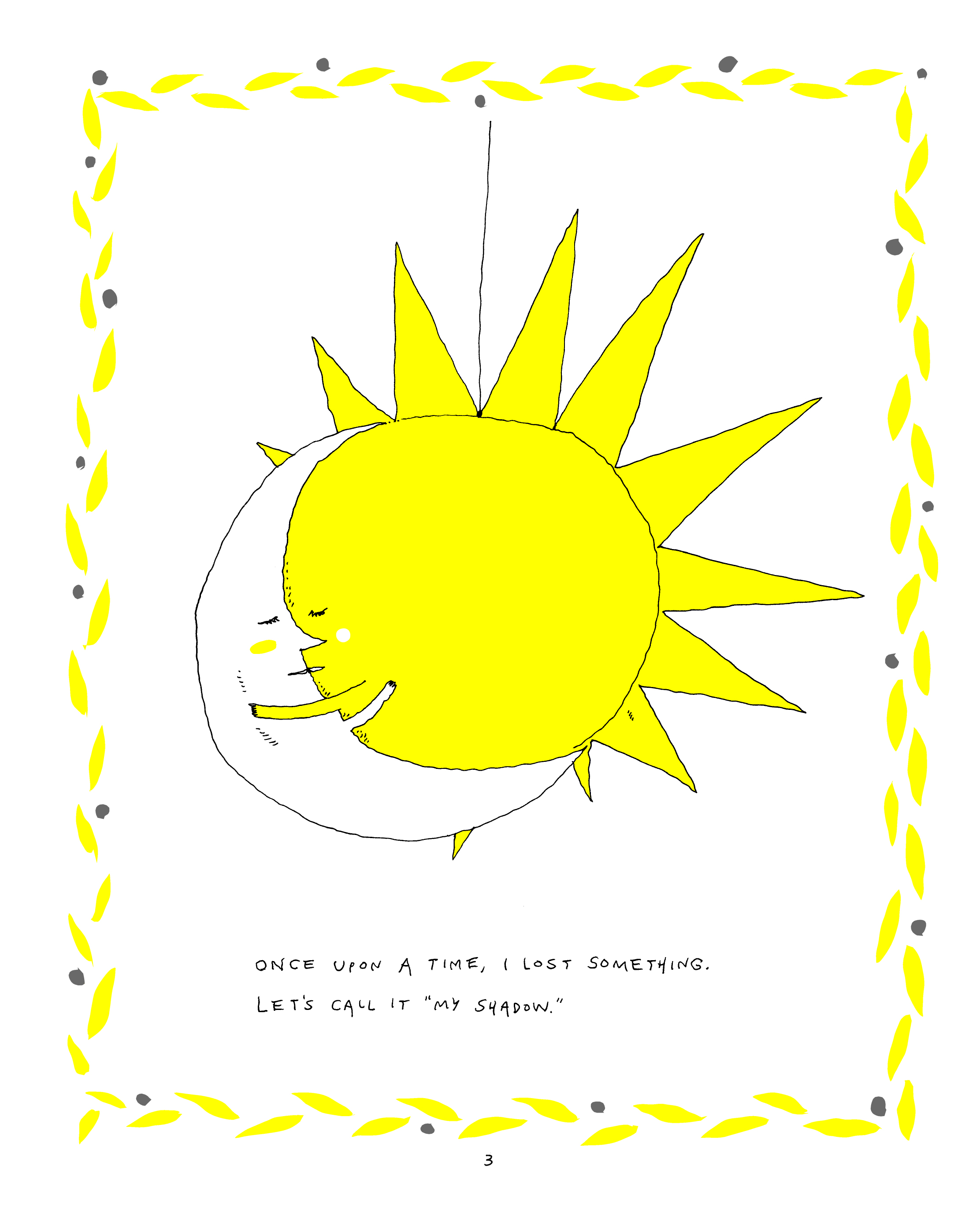

Liana Finck has a knack for noticing, and interpreting, human behaviors. Her quick-witted, quirky sense of distillation and humor is frequently on display, whether in her The New Yorker cartoons, on her Instagram (188k followers and counting), or in her longer published works. Passing for Human is her second book-length work of comics, and in it she turns her observational skills on herself. A graphic memoir, the story it tells is as much about the complicated process of piecing together a life as it is a narrative conveying the details of that life. In fact, the book is mainly composed of beginnings. Each central chapter tackles the protagonist, Leola’s, autobiography from a different vantage point, as she searches for her shadow, lost to her somewhere in the throes of adolescence.

Drawn in a serious, simple style reminiscent of Saul Steinberg, or some of Edward Gorey’s sketchier illustrations, the book’s recursive structure provokes more questions than it answers. When do our stories begin? To whom, or to what, do we owe our senses of selves as distinct from those around us? What, indeed, makes us human?

I sat down with Liana on a late summer day, over a bowl of fresh blueberries and two strong cups of coffee. We discussed her latest project, including her process, the motivations behind her book, and her favorite places to work.

— Tahneer Oksman

THE BELIEVER: What were the roots of Passing for Human?

LIANA FINCK: It started out a long time ago. I was very slowly finishing my other book, A Bintel Brief. In the gaps, while it was slowly grinding to a halt, I needed a new project. I really hate not knowing what I’m doing, so I chose to just give myself an assignment. The project was to adapt Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight. I was doing it pretty straight up. I was doing it badly. I was young, and I didn’t know I’m not someone who should be adapting novels.

And then my agent at the time asked the Nabokov Estate if I had permission to do it, and they said no. So, I started changing things around. I changed the two brothers to two sisters. And then I changed one of the sisters to a shadow. I’m very...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in