I met Megan Culhane Galbraith on Twitter several months into the pandemic when I was quarantining in isolation on the coast of southeastern Massachusetts and she was doing same in Troy, NY. I tweeted something about naps and Megan replied by posting a sleep chart with various figures in repose and explained that she was a “Supine Starfish,” to which I replied that I was a “Foetus” because I sleep on my side with a giant sturdy bed pillow between my legs, like a pregnant woman. This led to long exchange with Megan about the value of body pillows for sleep and self-care and within a week, she had procured the exact same body pillow I have.

As a fierce advocate for body pillows, I was impressed.

We ended up talking on the phone about body pillows and then other subjects and these were roving candid talks that cut against the ghoulish shadow of isolation that had settled over our newly traumatized souls in November 2020. Looking back, I cannot speak for Megan, I think I was in much worse shape than I realized at the time––I think I was starting to come undone––and am therefore moved when I consider of what value our phone conversations were in terms of me being OK. Those conversations with Megan offered the very real sense that we were navigating forward through the treacherous waters of the pandemic, which seemed to birth new trauma and horror every day.

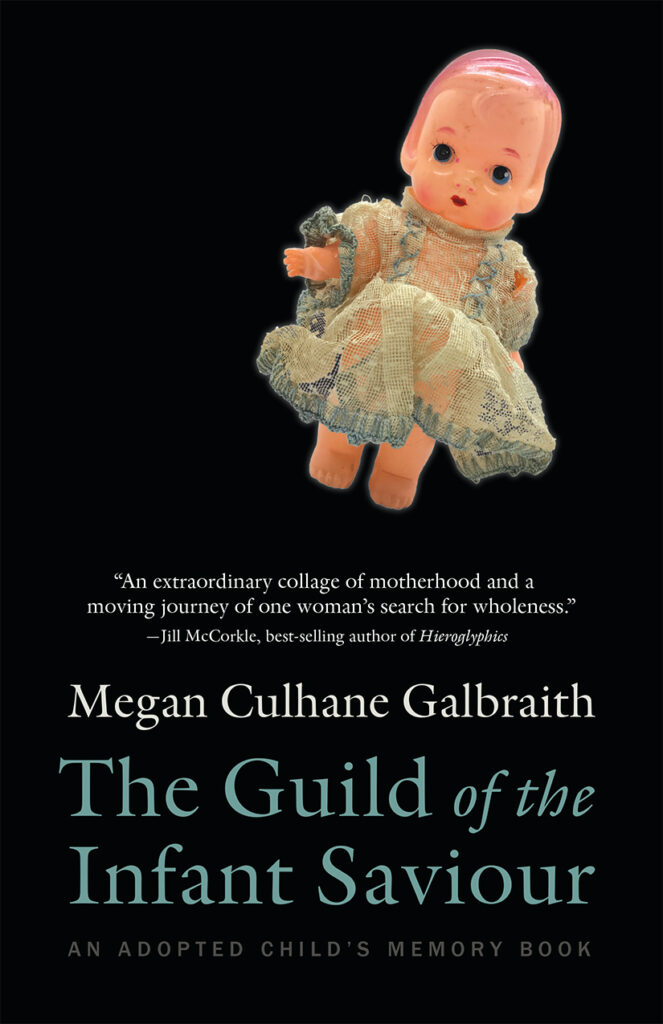

In her delicate and vulnerable debut, Megan was excavating her own trauma as an adoptee coming to grips with a life stitched together from the coping mechanisms of others’ memories and her own. What emerged is a deep exploration of self that is shot through the lens of stories we tell ourselves in order to live, as Joan Didion says. Using dolls and a dollhouse as the framework and structure for her hybrid memoir-in-essays, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book, she lets us wander through rooms that had previously been locked—where adoptee’s secrets are kept. Her writing weaves deeply vulnerable and personal stories with cultural research and substantive reporting. In it, she explores the “primal wound” that adoptees wrestle with––caused by the initial separation of baby and mother––and explodes the myths and the savior complex that muddy the voices of adoptees who speak up.

This is a stunning debut that, to me at least, signals the emergence of a major literary artist. Sort of like if Anne Carson wrote a police procedural in which she tried to solve the riddle of who she was in a previous life. It bears mentioning this book is published under Ohio State University’s new Mad Creek Book series, edited by Joy Castro, who is committed to publishing daring and experimental writing by diverse voices.

As we collectively emerge from this ghoulish shadow of isolation, Megan’s book reminds us to hold ourselves tight and to make peace with the inner child in each of us.

––Gabe Hudson

THE BELIEVER: You created a visual art project The Dollhouse where you staged small dolls in dollhouses and photographed them. In your book of personal essays about your lived experience as an adoptee The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book, you write of the Dollhouse art project, “It gave me the space I needed to examine my adopted life through a different lens.”

Would you run into a burning house to save your dolls?

MEGAN GALBRAITH: I would only run into a burning house to save my children and my laptop. Those dolls can burn; my art can burn; everything can burn; but I must save the words. I’d derive so much joy in filing insurance claims to buy myself new creepy dolls and another dollhouse. It reminds me of the year I filed my taxes and wrote off two pairs of handcuffs I’d used for an art show. If there’s one power we have as artists and writers it’s to use the system against itself whenever possible.

If my house were to burn down I’d begin again, but I’d probably buy fewer black t-shirts. I seem to have a hoarding problem with those.

Anyone who grew up with trauma, like adoptees, has likely wanted to burn down his or her childhood home at some point (or imagined wanting to do so), haven’t they?

Go ahead. Let the house burn.

BLVR: Do you feel any emotional attachment to the dolls? I have to confess after reading about your dolls and seeing their images in your book they do seem alive to me in a unique way. Like if I accidentally stepped on one I’d feel terrible.

MG: These dolls don’t have an emotional significance to me, per se, as much as they do an artistic and metaphorical one. Wait, I take that back. The doll on the cover, the one I call “Little Megan,” is one I have a deep attachment to. She is the embodiment of me. I remember picking her up out of a huge box of dolls my friend Elizabeth gave me. She’d sent me two boxes of dolls that were given to her mother when she was in the hospital for a year recovering from polio. This doll represents so many things at once—she is fragile, fierce, innocent, and resilient—like me.

The quote by Erik Erickson that I use in the prologue of my book is deeply meaningful for this very reason.

“Children are innocent before they are corrupted by adults,” said Erickson, “although we know some of them are not and those children—the ones capable of arranging and rearranging the furniture and dolls in any dollhouse—are the most dangerous of all. Power and innocence together are explosive.”

I’d say my “Little Megan” doll is irreplaceable. I wouldn’t forgive you if you stepped on her and my Scorpio besties would definitely come for you in the night and burn your house down.

BLVR: In your book, you describe how the experience of playing with dolls as an adult was a life-changing experience. You write that in playing with dolls you became, “curiouser and curiouser.” How did the experience of repeatedly going down your own personal rabbit hole inform the writing of this book?

MG: There’s a freedom to creating art through play. I was reading about one of my artistic influences, the surrealist painter and writer Leonora Carrington. Her work is whimsical and weird and always in the context of a fantasy world, or the confines of a structure that mimics a dollhouse. She’s a world builder. That’s what a dollhouse allows me to do: construct my own world-view.

I was interested to learn that Salvador Dalí had to unlearn his classical art training in order to tap into his “child brain” which is what generated the lasting works of art we have today. There is such power in play and returning to that beginners mindset. There is great strength in tenderness of a child; there is resilience and power in innocence.

Curiosity can be a double-edged sword when it is never satisfied. At the heart of the adoptee narrative is that our curiosity is endless because every new answer begs a new question. The searches for our birth identities become like rabbit warrens: dead-ending and doubling back upon themselves. We can become buried in those holes if we don’t come up for air.

Part of the life-changing nature of my particular form of play was the gift of understanding the depth of my trauma from having been adopted. Playing with these dolls helped to unlock that for me and that’s no surprise. Dolls and play are used in many forms of trauma therapy … a therapist might use a doll to ask; “show me where he touched you,” or another might use play therapy to alleviate anxiety for a child or to help them voice their feelings through the safety of the pretend.

BLVR: At times your sentences, graceful and stylistically compelling, also have a strong “I wish a motherfucker would” energy to them. Like you weren’t going to let anyone (including yourself) keep you from writing the truest version of your story in all its horror and glory?

MG: This is so true. In the late stages of editing I tried to channel Cheryl Strayed who said, “Write like a motherfucker.” It was hard when I had the negative voices in my head from my relatives, not to mention my own negative self-talk. I worried every damn sentence thinking, “What is so-and-so going to feel or think about this,” until I finally relaxed into the idea that I couldn’t carry that burden. I am not responsible for how someone else thinks or feels.

All we can do as nonfiction writers is write into the truest version of our story. I say this with humility, but I know my story was powerful because of the messages I received from other adoptees and readers who have been touched by adoption. It feels very lonely sometimes as an adoptee. When readers write to say my words had positive resonance for them it makes me feel less alone.

I opened my veins in writing this book. I made myself bleed a lot, but it was a necessary bloodletting.

Honestly, I wouldn’t give my detractors the satisfaction of fighting with them.

BLVR: Making art with dolls for you seems almost to be a way of entering a different dimension. What for you is the value in making art that directly accesses your “primal wound”?

MG: World building is part of the adoptee experience and it is also a child-like, innocent way of self-soothing directly related to the “primal wound,” which is a term coined by Nancy Verrier to represent the deep trauma of a child being separated from its mother at birth. That separation happens when a child is pre-verbal so it’s interesting to me that when adoptees begin to speak about this wound many of us are disowned, discredited, and distanced and cut out of our adoptive and our birth families again, which results in secondary abandonments.

When we go deep into our wounds as a form of self-discovery it should be celebrated not shamed.

Who wouldn’t want to build themselves a safe world? Who wouldn’t want to seek power in another dimension?

BLVR: This might sound corny, but I mean it sincerely. Is there a way in which your experience with the dolls imbues you with sense of extrasensory perception and understanding?

MG: That’s not corny at all.

When I was a child, I built dioramas, and made small worlds out of sticks, stones, and leaves next to the riverbed in the forest where I’d go to play. Perhaps it was a way of disappearing, but the woods––with the sun dappling the leaves and the fiddlehead ferns––became a magical fairyland. The time I spent in my own head was safe. It became a form of magic: a kind of divination. I still go to the woods and gravitate to water when I am hurt and want to be healed.

It was Einstein who said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand.”

All there ever will be. Isn’t that boundless and beautiful?

I’m thinking of the tarot right now and how I often I pull the Fool and the Death cards. To me, the Fool represents beginners mind. I want to always be beginning. Death is not literal of course, but a metaphor for rebirth. If I can channel my child-like imagination I have the opportunity to be reborn every day. That’s magical.

BLVR: These dolls are tiny, two inches tall or thereabouts: is there any significance for you in the fact that you or your doll experience are strongest when the dolls are miniature? Personally I find idea of what is smallest is strongest to be a seductive way of processing things.

MG: Miniature is mighty, indeed. Dolls are inanimate objects onto which humans project all sorts of ideas about sex and sexuality, motherhood, trauma, body image, and even murder (you have to whisper ‘murder’ out loud and draw out the u; ‘muuuuurder.’) If you haven’t heard of The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, take a look. Frances Glesner Lee’s miniature dioramas depict composite crime scenes and are so detailed they seem life-sized and gruesomely real. They became the basis for modern forensics and have been used to train crime scene investigators.

I recently had an art show called RELIQUARY in a 1:12-sized gallery. I beheaded and bedazzled dolls in homage to female Saints who’d been corporeally mutilated because they wouldn’t bow their bodies to the will of men. I can’t tell you how many people thought it was a full-sized gallery. Friends wanted to come for the show’s opening and I had to tell them the entire gallery was atop a small table in the studio owner’s house. It’s delightful to be able to trick people’s perception like that. It feels powerful. Shifts in perspective can cause some tremendous mind-fuckery.

BLVR: In the same vein as the trickster archetype, that sort of mind-fuckery?

MG: Oh, for sure. The trickster is a dark archetype. But put the trickster up against a bunch of dolls and he becomes laughable. These booby, leggy dolls defuse the trickster’s power. I use them as a shield against the darkness. I play with hyper-sexualized dolls in a 60s-era dollhouse. These toys are typically associated with femininity and home, yet what I’m conveying challenges those foundational beliefs. I’m giving them great feminist power in order to subvert the dominant patriarchal paradigm.

In his essay, “The Philosophy of Toys,” Charles Baudelaire writes “All children talk to their toys; the toys become actors in the great drama of life, scaled down inside the camera obscura of the childish brain … the toy is the child’s earliest initiation into art, or rather it is the first concrete example of art …”

There’s innocence, control, and intentionally in using dolls this way.

BLVR: What about that shift in perspective for the creator, the artist––are you intentionally performing mind-fuckery on yourself as well?

MG: Hahaha! We’re writers. We’re always intentionally performing some sort of mind-fuckery on ourselves, aren’t we?

The beauty of the miniature is that it forces us to not just “look,” but to actually “see.” Taking a photo of a scene captures that scene in the third person. By looking you become a voyeur. Coupled with the immediacy of the essay it creates an unexpected whiplash for the reader.

By recreating my baby book photos in The Dollhouse at front each essay (and then using my original photos as artifacts at the end) I hoped to create an invisible thread for the reader that felt umbilical. My hope was that as a character, the reader would see me in multiple dimensions and from the same prismatic angles through which I was examining myself. I wanted the book to evoke the feel of a children’s picture book, like The Lonely Doll, which has been a huge influence on my work.

BLVR: At one point in your book, the author Mary Gaitskill tells you about her doll Beautiful Sue that she kept from childhood on into adulthood and how she eventually put this doll in a shoebox and buried it. Then Gaitskill says, “I feel like she wants me to come back for her. But I can’t be sure I remember where I buried her.”

To me this quote seemed like an apt description of your undertaking in writing this book. As an adoptee, the vigorous detective work you chronicle in your book in order to discover the truth about your past––did it ever feel as if there were another version of yourself that wanted you to come back, one that you had buried?

MG: In fact there IS another version of me. That’s exactly what being adopted is about. I have two identities, two names; two different versions of myself exist in a parallel universe. For adoptees, it is our life’s work to wrestle these two very different angels. I felt largely invisible as a child. I tried to not make waves for the perceived fear that I’d be abandoned again. It’s a primal fear that lodges itself in your pre-verbal cortex.

We adoptees have rejection baked into us. We are told to hush; to bury our pain and to be grateful for being rescued. This is a burden. This is what we bury. Adoptees are four times more likely to attempt suicide.

BLVR: While I was reading your book, I was struck by powerful sense of how immensely useful this book would be to other adoptees who have writing aspirations.

To that end, there is a chapter where you describe going to a writing residency and we witness your writerly pain and despair. But also the joy in how your writer’s mind could save itself. To use the vernacular of the internet, that chapter seemed to me a very complicated and fascinating flex.

My question: were you consciously modeling an example for other writers in chronicling your process in writing this book?

MG: It has been a great gift to hear from adoptees who have read my book. They’ve told me how resonant my experience was to them and that feels so validating because as I was writing it I hadn’t yet fully tapped into the adoptee community. I was writing in a vacuum and feeling alone in my thoughts. I was trying to honestly wrestle with my own pain while sitting in the “poopy diaper” of my grief. That’s what writers do isn’t it? That struggle is universal. Perhaps that’s why that particular essay felt like a flex. But to me a flex implies a performance. I wasn’t performing pain or grief; I was IN terrible pain and grief.

BLVR: Conversely, can you tell me what other books helped you in the journey of writing your book?

MG: My book list ranged from children’s books like The Lonely Doll, to The Girls Who Went Away by Ann Fessler, to scholarly books like Abandoned: Foundlings in Nineteenth Century New York City by Julie Miller. These were influential to, along with Mark Wolynn’s It Didn’t Start With You about the effects of epigenetic trauma.

I am a huge fan of Karen Green’s, Frail Sister. She’s a genius. And art books for Hieronymus Bosch and Hilma af Klint helped me think about form and structure. Seeing Betye Saar’s work at MoMA validated my use of found objects and reminds me of how mystical the process is. I love her phrase, “you can make art out of anything.”

I read a lot of census data and crosschecked birth records via genealogy websites. Much of that may seem dry, but when I stumbled on the census listing for, say, the “crazy Hungarian boarding house” that my birthmother told me about it was visceral to see the names of the immigrants who lived there, written in old-style cursive. Going back into the genealogy wing armed with my birthmother’s name was also grounding. Seeing my birth name listed there (my middle name was my given name) made me feel “real” in a way that’s hard to describe to someone who’s not adopted.

BLVR: Personally, I am stupefied by and admire to no end the courage and strength that you summoned in order to write this book. To any adoptee writers out there deep in the struggle, or on the verge of quitting, can you offer any perspectives that enabled you to power forward and keep writing?

MG: Thank you, Gabe. Anyone who is writing from a place of trauma deserves all the praise and support because this shit is hard. I’m not much for giving advice, but I will say I am glad that I didn’t give in to the negative voice inside me that said this book or my voice wasn’t worthy.

Right before the pandemic set in I thought, “I don’t want to regret not trying my hardest to get this book into the world.” It had been sitting in a file, untouched, for at least two years because the subject matter was so tender and I was afraid of it. Fear is a great motivator to keep myself small. I faced my fears writing and publishing this book. I’ve been transformed in ways I’d not imagined. I’m stronger for all of it.

BLVR: As a reader, it felt like you encountered an enormous of resistance to you writing this book, from some of your family members as well as the world at large. What did it feel like when someone close to you who ostensibly is supposed to have your best interests at heart discouraged you from writing the book?

MG: As essayists and memoirists know, writing about oneself and one’s family is a fragile endeavor. The people closest to me were the ones capable of inflicting the most cruelty and they did. In my case my siblings (one biological, the other adopted) and my birth mother all abandoned me for using my voice (ironically my siblings aren’t even identified in the book.) Those closest to me in adoption were the ones who reacted most negatively. As I say in the book; shame is spring loaded.

After the initial shock and betrayal, I realized my focus is better served with those who support me like my best friend and cousin, my father, my stepdaughter, my sons, my friend family, and other adoptees. As adoptees we’re told to hush. It hadn’t occurred to me I could choose to set boundaries. There’s immense power in boundaries especially in witnessing who respects them versus who continually crashes through them.

Gina Frangello, author of Blow Your House Down, is a writer whose courage and voice I greatly admire. She inscribed her book to me with two powerful words: “Never hush.” While that’s sometimes easier said than done, I may just tattoo that phrase on the tender skin on the underside of my arm.

BLVR: At one point in the book, by examining your birth certificate and other documents, you discover a chunk of time early in your life where you were not accounted for. You had literally disappeared. How did you feel when you realized this? Was it terrifying, in that you had to wonder if there might be other times from your life that were unaccounted for?

MG: Well, I had to chart my first months on a Day-Planner calendar in order to realize a gap of almost six months. My whereabouts was unknown. That was, uh, weird to say the least. It’s a bit like an out-of-body-experience. Seeing that first-ever photo of me, the one I talk about in the book, felt like adult-me was floating over the body of baby me.

My mom referenced “the home” once or twice when I was young, but I didn’t think to ask her what that meant at the time. That she noticed the “flat spot” on the back of my head and guessed that I hadn’t been picked up a lot is interesting and sad in retrospect. I wonder if my parents knew where I was? My Dad always thought I was “with the nuns.”

My training in journalism taught me how to dig for details, but it was sheer luck that I got a caseworker on the phone that empathized and gave me information she wasn’t supposed to about my foster family. Had she not told me where I’d been, I’d still have a huge gap in my life.

BLVR: This book would appear to mark the end of a long artistic and spiritual journey. Are there any remaining aspects of your lived experience as an adoptee that you want to uncover the truth about?

MG: I do want to find the children of the foster family I lived with so I can ask questions about what it was like for them to have fostered children like me. I’m curious about what they think and would love to fill in the blanks about what their parents had been like. Were we taken in for money? Were they benevolent and kind and just wanted to be temporary parents to adoptees in transit?

Access to this kind of information is a basic human right. As adoptees, we shouldn’t have to guess, or ask questions. Life is hard enough. We should be able to know where we come from.