“Now that I’m older, it strikes me as incredible that I went into those places as a young woman. Meanwhile my friends in New York were hanging out with Chloe Sevigny at the chicest, prettiest parties. I was like, ‘I’m at a Best Western in the middle of nowhere with bikers, going to a prison tomorrow!’ I thought, What is wrong with me? I must be a fucked-up person.”

True Crime Has Been Perceived As:

A Sophisticated Area of Inquiry

Lurid and Sensational

A Testing Ground for Moral Clarity

Rebecca Godfrey was twenty-seven, finishing her first novel and living in downtown New York City, when she returned to Victoria, the idyllic small Canadian island town where she was raised, to report on a previously unprecedented act of teenage violence: the murder of fourteen-year-old schoolgirl Reena Virk, who was beaten and drowned at the hands of her peers in the November of 1997. All but one of the teenagers involved in the crime were girls. What began as a magazine article became Under The Bridge, a literary non-fiction book about the events and their aftermath, which will be reissued this summer.

Girlhood, throughout Godfrey’s body of work, is a space of violence as well as vulnerability—she recognizes that one does not discount the other. In one scene from her first novel, The Torn Skirt, she describes a teenage prostitute who cradles a bottle of Love’s Baby Soft perfume “like a tender grenade.” In Under The Bridge one could say that grenade explodes, and there is an eerie echo of that moment when, after fleeing the scene of their crime, the real-life characters rifle through their victim’s backpack and smash her bottle of Polo Sport on the ground. The glass shatters, the sweet smell evaporates, but later detectives will return to pick over the shards, looking for clues. Sometimes art doesn’t merely mirror art; it precedes it, like a premonition.

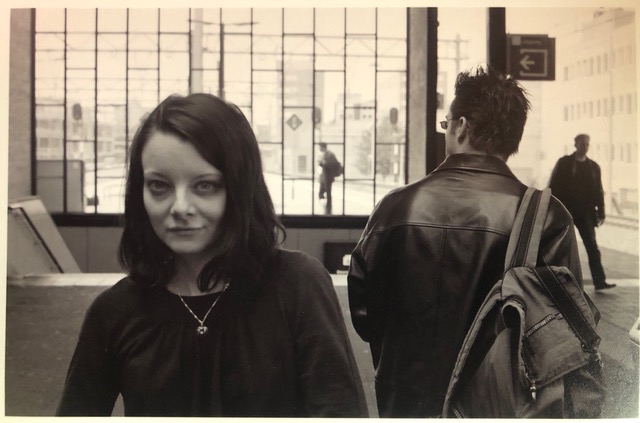

If being “physically small, temperamentally unobtrusive” was an advantage for Joan Didion, the same might be said about Godfrey, who is petite, with a soft speaking voice and eyes of ethereal blue. She is shy, though often disarmingly frank, in a way can be both charming and quietly intimidating. It is easy to see why the youth of View Royal would have been drawn to her and chosen her as a rare confidante, with her cool intelligence, her empathy, and above all, her grace when confronted with life’s darker subjects—the same reasons I have counted on her counsel since my days as her student in the graduate writing program at Columbia University.

For the first time, we sat down to discuss the events of twenty years ago and the process that took her deep into the world of the youth involved—to police stations and detention centers, courtrooms and foster homes, to classrooms and bedrooms in suburban View Royal full of the regular detritus of teenage life: snapshots from sleepovers taped to the walls alongside posters of Leonardo di Caprio, Calvin Klein jean jackets discarded on the floor. Places where girls dreamed and wrote poetry, listened to hip-hop, and two best friends first talked on the phone about how to carry out and cover up a murder. In conversation Rebecca Godfrey is as generous as she is as a professor, mentor and friend. We gathered in her best friend’s room in Chinatown, a little like two teenage girls, and talked for hours.

—Madelaine Lucas

I. Beware of Young Girls

THE BELIEVER: I was surprised to learn that before writing Under The Bridge you’d had little experience as an investigative journalist. What compelled you to seek out the teenagers involved in the murder of Reena Virk and tell their story?

REBECCA GODFREY: When I first heard about the case, I was living in New York City. I had graduated from the Sarah Lawrence MFA program and was writing The Torn Skirt, a novel about runaway girls getting into trouble in Victoria. Friends called me and said, this girl was killed in Victoria, and they’ve arrested a bunch of girls. It’s just like your novel. I read the article in The New York Times and the teenagers they interviewed were very vague—saying “something happened,” and that the motive for the crime was “rumors.” It was fascinating to me that something had happened in my hometown involving young girls.

I was given an assignment from a women’s magazine to write about the fourteen year-old girl who was accused of the murder, Kelly Ellard. The media said her school nickname was “Killer Kelly” but in photographs she looked very prim and delicate.

I went back home to Victoria, and sort of bluffed my way into the juvenile detention center. I didn’t know enough to call the warden or go through any official channel—I called the head of youth programs. I guess my voice sounded young because he assumed I was working on a school project. He gave me a tour, and when I was leaving, I bumped into a reporter I knew who was writing about the case for GQ. He said, “How did you get in there? The warden isn’t letting journalists in.” I think that was my first hint that not being part of the established media could be helpful.

BLVR: What was the atmosphere like in the prison?

RG: It was co-ed, and they were used to having one or two girls there for vandalism or prostitution, but they’d never had girls in for murder before. And now there were seven of them. They were running out of space, so girls were sleeping in the TV room. It was a very chaotic scene.

There were signs that said “KEEP ELLARD AWAY FROM OTHERS.” I went up to the cells and the girls were like animals in a zoo—they would come up and look at you against the glass. They had posters of Aaliyah or Tupac on the walls. They were all different races—some looked terrified, some looked really defiant. I thought, how did they get involved in this? Who are they?

The crime was front page news around the world, but no one could provide any details about the girls because of Canada’s Young Offenders Act, which prohibits publishing the identities of minors. Reporters would call them Girl X or “Sally.” Because I’d seen them, I was very aware of the disconnect between who they seemed to be and who the public wanted them to be. I remember a movie producer calling me, and asking, “Are they cheerleaders? Or are they gang girls?”

BLVR: What first drew you to writing about rebellious teenage characters in The Torn Skirt, and then Under The Bridge?

RG: I had a fraught and very difficult teenage experience—my brother drowned when I was thirteen. I went a little wild after that and lost interest in high school, and got into the punk scene in downtown Victoria. Being in that scene was great because I could hide behind this mask of anger and coolness and toughness, and think, “Oh, I look scary, so everyone will leave me alone.” In retrospect, I’m sure I didn’t look as tough as I thought I did [laughs], but the music and that crowd was a good disguise. My first novel, The Torn Skirt, was very autobiographical. I started it at Sarah Lawrence, when I was twenty-one.

BLVR: Why do you think people are so unwilling to recognize the anger or frustrations of young girls? Why are those experiences so often ignored or not represented?

RG: It’s hard for me to answer because I’ve always been interested in that. Even in high school, I was drawn to outcasts. There was this punk girl gang, the Speed Queens, in Victoria who wore motorcycle jackets and black lipstick; they had a fanzine, bands. I was very intimidated by them but also fascinated. I also loved reading murder mysteries with female detectives or suspects. I loved all the femme fatales in the Chandler and Hammett noirs.

I think there’s a resistance to the rebel female, which is something I was trying to get at in both [my] books. It’s part of the social contract. The idea that young girls could be violent, could perpetrate violence isn’t shown as often as we see girls seducing older men or killing themselves. It’s like, “This is what we want girls to be.” When Under The Bridge was optioned for film in 2005, I think studio heads couldn’t imagine that anyone would want to see girls who were murderous or brutal. It’s been interesting that since then there’s been The Hunger Games, Gone Girl, Big Little Lies.

But, as Mary Gaitskill gets at in her new introduction, the reality is so different. We’ve all known how cruel teenage girls can be, we’ve all experienced that. I think Megan Abbott has a good grasp on how right that reality is for murder mysteries. That actually the true narratives of girls’ lives, whether they’re cheerleaders or whether they’re gymnasts or whatever they are, there is a lurking violence there.

II. Capote For Girls

BLVR: You’d written a novel before working on Under The Bridge. When you started researching the Reena Virk case, did you ever consider writing this book as a fictionalized account of events?

RG: No, I didn’t. It was so incredible as truth. I wanted to have the reality of an investigation and a trial. I found the courtroom fascinating. The collision of the very official world of police, judges and lawyers—which was, in this case, almost one-hundred percent male—coming up against these young girls was so unusual.

BLVR: What were the challenges, as a fiction writer, of dealing with real events and real people?

RG: The interviewing was easy for me. I think I had an instinct or knack for it, and I wasn’t threatening to people because, at the time, I looked very young. There’s an investigative reporter who talks about how being small and delicate made all these men open up because they just didn’t take her seriously. I certainly found that to be the case. When I look back, it was actually quite an effective device to be a young woman.

BLVR: How was this different to interviewing the young people involved in the crime?

RG: It was a very different dynamic with the teenagers. I wasn’t as interested in getting official facts from them. I was more interested in getting a sense of what their lives were like, who they were. I think they trusted me more instinctively because they could tell my interest was genuine and I stuck around. Most of the reporters who were chasing them flew in for a weekend, for a “hit” and were gone. I was there for years and years. [Laughs] Many of them didn’t have adults they could talk to, particularly about events they were ashamed of, so I think it was cathartic for them to have these conversations.

I really liked these kids and I felt a real responsibility to them, but as a “journalist” you’re not supposed to have any emotional attachment. I think any reporter who spends a lot of time with their subjects who are in difficult circumstances comes across these type of ethical conflicts. There’s a certain intimacy with interviewing if it’s done well—there’s concern and understanding and honesty—and then you have to draw back.

There’s the famous Janet Malcolm line about how journalists prey on people’s vanity and ignorance, and then betray them without remorse. I really disagree with that notion. I think it’s very cynical and cold. I left things out of the book if I felt they would endanger or humiliate anyone. The story was good enough that I didn’t think I needed to betray anybody.

BLVR: What was the process like of earning the trust of the teenagers involved?

RG: It was a slow process, I was very scared. I’d interviewed Julie Dash, or Cherie Currie from The Runaways—whoever I found interesting—for different magazines, but I hadn’t done reporting on this scale at all. I read some books and sort of tried to teach myself how to interview, but that all fell away because this was so specific and unique in terms of talking to teenagers. I think I was a good listener, and I knew how to talk to them about their lives because it still felt very close to me. For example, when I called Warren, [who was serving time for his involvement in the murder of Reena Virk], the first thing he said was “Who have you talked to?” He really just wanted to hear about his friends: “Does Tommy still live there?” “Who’s Marisa dating?” He wanted me to be a conduit to that lost world of his, and I did know all the kids and gossip, so I was able to do that. It was very unconventional interviewing.

BLVR: The main narrative in Under The Bridge is the story of the murder of Reena Virk, and all the ways in which forces collided for that happen. But there is almost a subplot of this teenage love story between Warren, the fifteen year-old boy who is accused of the murder, and his girlfriend Syreeta. What did their story reveal to you, and why did it feel important to include it?

RG: I needed a counter balance to the more ruthless girls and I found Warren’s girlfriend, Syreeta, to be a really moving character. I also found their love story important as a dramatic event. They had this dreamy, adolescent moment of first love, and it was interrupted by such terrible violence. I had a lot of compassion for the aftermath of a death when you’re young and how difficult it was, when I was that age, to make sense of it, and to feel so much guilt and loss and grief.

BLVR: Syreeta shocks the police when, after her giving her police statement, she begs to see Warren—who has just been arrested for murder. As incredible as it may seem from an adult point of view, I don’t think a lot of the young people involved could really grasp the permanence of what happened. In that moment, her feelings of her first love are so much more real to her than the fact of the murder.

RG: Yes, that’s right. The police were saying to all the kids, “This is murder! A mother has lost her child.” And the teenagers still didn’t want to talk. They just did not want to cause harm to their friends. Those friendships were so fierce in a way adults can’t understand. There was this ferocity of loyalty. I think that’s something you lose as you get older, you have different things in your life that take priority. And they didn’t know Reena—it would have been one thing if she was one of their friends,; I think it would have had more reality to them.

Once police found Reena’s body, things began to change. At that point, it did become more real. Before that, it was just “187 on an undercover cop”—it was just a word in a song.

BLVR: In the book there’s a photo of you visiting Warren in prison. What was that experience like?

RG: I had to drive to the prison by myself on dark mountain roads. I got to the Best Western in this town called Mission and there was a motorcycle convention that weekend, so the entire place was full of bikers. I think I was the only woman at the hotel [laughs]. And then I had to go to this all-male prison.

I went as Warren’s guest. He didn’t want people to know that he was being interviewed because that was against the code of prison—he would have been seen as a rat. His story was that I was a friend from the island. On later visits, I concealed a recording device with his approval, but I remember the first time, we spoke for a bit, and then I went to the bathroom and wrote everything down.

At that point, he was in a medium security prison. It wasn’t like you see on TV, we weren’t separated by a glass wall. It just had this aura of being a perfectly normal place, it wasn’t institutional. In Canada, prisons are a bit more humane. At first, we sat in an open room, with other men nearby. I would start talking to someone and Warren would say, “Don’t talk to that guy. He decapitated his wife.”

BLVR: Did you ever consider including some of those experiences in the book?

RG: I thought about it. I mean, I think that’s a very American thing—to interweave your own story into the reporting. When it was optioned for film, my agent called me and said, “They want to do Capote for girls.” But I hadn’t written my experience into the story. I don’t know if it was an issue of ego, or an artistic choice, but either way, I didn’t think my role as reporter was interesting or necessary. I suppose I was also skittish about the parallels with my own life. I didn’t want to talk about my brother’s death or my own troubled adolescence in Victoria.

Now that I’m older, it strikes me as incredible that I went into those places as young woman. Meanwhile my friends in New York were hanging out with Chloe Sevigny at the chicest, prettiest parties. I was like, “I’m at a Best Western in the fucking middle of nowhere with bikers, going to a prison tomorrow!” I thought, What is wrong with me? I must be a fucked-up person.

III. To Catch a Killer

BLVR: There is an emphasis on the power of narrative in Under The Bridge. A group of girls plan to punish Reena for making up rumors; the murder itself is revealed through gossip and whispers in schoolyards and bedrooms. That would have been really interesting, as a novelist.

RG: Yeah, definitely, the role of story-telling within this story fascinated me—that the motive for the murder was tied to the fact that Reena told stories about some girls. Then after the murder, Kelly told stories about what happened and these stories were elaborated as they were passed around. My favorite scene in the book is when Kelly stops this boy on the street who she doesn’t know and starts telling him what she did. Her confession-slash-boast, the way it’s delivered, and the way it’s received by this boy, was really incredible. He’s just listening to this teenage girl go off, thinking he wants to hit on her, and she’s talking about blood in the water.

BLVR: There’s a chapter in Under The Bridge that almost reads like a vox pop of people in the community that really illustrates how a story about a group of individuals can be repurposed for various moral, or political ends. How did you come up with the idea for that chapter?

RG: I used actual letters to the editor to create a montage of voices of the town. When I was promoting the book, I did a lot of talk radio interviews and they would just say [in the voice of radio announcer] “Why’d they kill her? Thirty seconds!” And then they would go back to the weather. They would hit me with these questions—“Kelly Ellard’s a monster, isn’t she?” That was the way of processing this incredibly complex thing.

Looking back, there are two ways you can view something like that. You can view it as a criminologist, which I wasn’t. I viewed it more as a tragedy, as we see in literature. There were certain forces acting on these characters, who found themselves in this unlikely, heartbreaking story. And so, when I was on radio, I couldn’t give the answer a criminologist would give or a social scientist would give, and that’s what people wanted. I just wasn’t viewing it that way.

BLVR: There are references throughout the book to Romeo and Juliet, especially in the Warren and Syreeta relationship plot. They even nicknamed him “Little Romeo.” A lot of the events do come across like a classic tragedy— there’s so many points when things could have gone the other way, but for whatever reason they didn’t. There’s that sense of “if only”.

RG: Definitely. As a story-teller that was really interesting. These twists of fate, and how one thing led to the next. Also, I always loved the idea in Crime and Punishment of, do you get away with it? And the chase of trying to catch the killer, and in this case, it was quite hard for them to catch the killer.

BLVR: What was the process like of covering the trials?

RG: The teenagers all told me different stories than they told on the stand, and I found that really revealing and significant—it showed me how a novelist can get at a much larger story. I would sit at the trial and see all kinds of details that would strike me—emotional moments, or uses of language. Then I would go back to the hotel and it was always the first story on the news, and it would be reduced to the most sensational line: “Today, a school friend of Kelly Ellard’s said Kelly boasted of smoking a cigarette while drowning Reena.” All these other details, like Kelly’s mother handing her daughter a lipstick over the barrier, weren’t told—they don’t have the space for it in a headline. And the same with these kids when they were talking to the police. They would be asked facts and they would give the facts, but the stories they told me had much more richness and emotion.

BLVR: I’m interested in this idea of these two parallel investigations—your process of search and discovery would have been so different, and the kinds of truths you were looking for would have been different kinds of truths, I imagine.

RG: It really altered my sense of justice and criminal trials. We believe it’s a truth finding mission, and that’s absolutely not true. Lawyers are there to convict or to get someone off and they do what they have to do, but they really aren’t interested in truth. The truth is a complex, shifting, intangible thing. I do feel, with art, there is a different kind of truth, compared to the legal truth, or the conventional narratives the media spins out. There is perhaps a deeper truth in art.

IV. A Village Full of Sweethearts

BLVR: When Truman Capote wrote In Cold Blood, he’d read about the murder in the paper and moved to Kansas from New York to cover the case. You, however, grew up in Victoria, where the events in Under The Bridge take place. What were the advantages of being a local?

RG: I think Capote had more of a romantic idea of the small town. Because I’d grown up in Victoria, I didn’t come to it as an outsider. I had an ability to slip back into a life there, and then I would go back to New York. It was very jarring to go from this downtown life in New York, where no one knew about this case or these people, and then return to this intense world of trials and prisons. I moved between those two worlds for many years.

BLVR: I love the way you describe the town of View Royal as a “a village full of cousins and old sweethearts and drinking buddies and lifelong friends.” There’s an interesting tension in the setting between idyll and violence. In what ways do you feel like the character of the town was changed by the murder?

RG: Unfortunately, I don’t think it changed. I really thought that with the collective questioning of an entire community asking, “Why did this happen?” and “What can we do?” there would be more of an effort to improve the support systems for girls who are, as they say, “at risk.” That didn’t happen. They shut down Seven Oaks [the youth home where several girls involved in the crime, including Reena, had stayed] because it was getting bad publicity [after the murder.] And then when I talked to the mayor he was saying, well, we’re going to start a casino and with the funds from the casino we’ll build a youth center. That seemed like a really bad idea to me, to put a casino in this hard-partying town.

There was a really disturbing level of rationalization that I saw, and I think you see it often—that people find a way to rationalize their own lack of good behavior. People kept talking about the kids being monsters, but I was surprised the adults didn’t look at themselves and the way that they were raising or not raising their kids. When I spoke with teachers or principals or people who were in a parental position, nobody acknowledged any kind of responsibility. There was a lot of adult hypocrisy and hand-wringing. And they still haven’t built that youth center.

BLVR: With some distance and perspective, why do you think the case became such a media sensation?

RG: It was really shocking. It was before all these cases of violence in high schools. It was before Columbine. A group of teenagers not only killed another teenager, but that they kept it quiet for a week, and nobody came forward to the police.

Also, it was in Victoria, which has a reputation in Canada as this postcard-pretty place, where you go for vacation to look at the forests and go sailing. It’s a former British colony, named after the Queen, so it has an aura of being very proper and stuffy, with tea rooms and perfect gardens. If it had happened in another city in Canada, I don’t think it would have received the same attention.

And it was really a mystery. Nobody knew what happened or why it happened. None of the kids confessed. There wasn’t a typical villain at work, like a disheveled old… who is the killer in Twin Peaks?

BLVR: I think it was like, the spirits of the forest.

RG: There wasn’t a Ted Bundy, or a bogeyman.

BLVR: It wasn’t supernatural.

RG: It was like, your son or daughter did this. And that’s what one of the lawyers said to me. “I was looking at my own kids.”

V. Bard of Bad Girls

BLVR: What do you make of the recent rise of true crime, with the popularity of shows like Making A Murderer, or podcasts like My Favorite Murder and Serial?

RG: Now that true crime is considered a prestigious or sophisticated area of inquiry, I realize that when I was writing Under The Bridge, the genre was looked down on as lurid and sensational. It was associated with books like The Stranger Beside Me, and seen as a little trashy. I didn’t have this attitude, because I had loved In Cold Blood—and it didn’t interfere with what I wanted to write—but there wasn’t the same attention or interest in crime that there is now. I had so many people say to me, “Why would you write want to write about that?”

BLVR: Why do you think that feeling has changed?

RG: I think true crime is an engaging way to get at hidden aspects of human behavior, particularly anger and desires. Also, it raises an essential question about guilt and innocence. Right now, in the era of Trump, I think there’s a longing for moral clarity. We want to know who the good person is, who the bad person is. Whereas, I think there used to be more of a romantic fascination with the outlaw.

BLVR: We talked about In Cold Blood before. Were there other models you looked to as inspiration for how Under The Bridge might take shape?

RG: I really tried to find a book that had done what I wanted to do. I read everything from Ann Rule to Norman Mailer and I really couldn’t find any model. Most books were dealing with an adult male killer, and there was a certain voyeuristic quality to the killing of women that I wanted to avoid. I found more inspiration in literature—in Wuthering Heights, in Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, in Passing by Nella Larsen, these really extraordinary novels with violent female characters. There is actually quite a lot of crime and violence in writing by women, even though it’s often not presented that way.

BLVR: It does strike me that what we hold up as the biggest examples of literary true crime, In Cold Blood and The Executioner’s Song, are both books by men, and they deal directly with ideas about masculinity. The popular examples of violent young girls are usually in cults, like the Manson family, or there’s a boyfriend involved. What’s so different about Under The Bridge is that there was only one boy involved, and the murder wasn’t motivated by the love or attention of a man.

RG: Yeah, the crime was for other girls. Even in Twin Peaks, which captures the particularly weird Pacific Northwest vibe I grew up with—of forests and rain and strange characters—all the teenage girls are essentially vixens and victims. It was exciting to write about girls who really defy all the stereotypes. Some of these girls wanted to be gangsters; they wanted to have power. Some of them were incredibly moral and bold. Reena herself was bullied but also had a lot of verve and courage.

BLVR: Under The Bridge was first published in 2005. Since that time, you’ve had a child of your own. I’m curious how the experience of motherhood and raising your own daughter has impacted the way that you look back on those events.

RG: I remember when I was writing the book and friends of my parents or older people would ask me what I was working on, I’d mention the Reena Virk case, and they’d say “Oh, I can’t even read about that!” When I was in my twenties, I would think, you should be a witness, this is your society, it’s your role as a citizen to know what’s going on in the world! I could not understand their aversion, and now I’m exactly the same! There is no way I could write about a murder involving a young girl now that I have a daughter. Whatever damage and violence I was drawn to, I’m just not drawn to it anymore. Though there’s violence in my new novel, so maybe I am [laughs].

BLVR: I actually wanted to ask about that, because I know you’re currently working on a novel that’s based on the life of Peggy Guggenheim. When did you become interested in her story?

RG: After Under The Bridge, I had a few editors approach me to write for magazines or do more investigative reporting. I really wasn’t interested in crime—I was interested in that crime. I was very haunted by those kids and that story, and it took me a while to get it out of my system and figure out what to do next, and then I had a child. At some point, I had the idea of wanting to write a love story or something completely different. I had been tagged as the “the bard of bad girls,” and I didn’t want to do that anymore.

My grandmother had just died, and I found in her closet Peggy Guggenheim’s autobiography. I started reading it and was like, “How did I not know about this woman before?” There was so much in her story that drew me to want to write about her—her relationships with these very radical women like Emma Goldman and Djuna Barnes, and particularly the fact that she had an affair with Samuel Beckett, who is my favorite male writer. I’ve always been fascinated by him, and wrote a very pretentious college paper on Krapp’s Last Tape [laughs]. They seemed like such an unlikely couple, and I loved the fact that they had this torrid, insane love affair before they were both famous. It’s not something many people know about; I certainly didn’t. So, initially, I thought, I want to write about this love story. Having a child, I didn’t want to be in that space of darkness anymore, but of course, Peggy Guggenheim’s story also has a lot of violence.

BLVR: Her story is marked by tragedy as well.

RG: Tragedy and loss and grief. So I kind of ended up back there, writing about dark stuff [laughs]. It’s a novel, but my curiosity about her has led me to end up doing a lot of research. It’s detective work, I guess. Going to archives, tracking down missing manuscripts, interviewing people who can provide the kind of details that we spoke about earlier, poetic details that are real but haven’t been part of the historical narrative. There are so many myths about Peggy Guggenheim—that she was a terrible mother, that she was some sex-starved, kooky socialite, but I don’t see her that way at all. It really is about finding the untold story. It’s very similar to reporting.

BLVR: Your books have centered around unconventional, unruly female characters. Would you consider Peggy Guggenheim, also, to be an antiheroine?

RG: Oh yeah, completely. And that’s what’s fun about the book. I don’t think there are many epic books about women moving through history. I think of the movie The Aviator as a model—stories about these legendary American men. Her story is intertwined with these great moments of social change from the Titanic, through anarchism and modernism, Hitler, and American postwar exuberance. She was very unconventional in her time and within her milieu as the daughter of a very powerful Upper Class Jewish family. Even as a teenager, she was shaving off her eyebrows and working at a downtown bookstore.