“Art is something you use to define yourself.”

Things considered “boring” that Seth finds really quite interesting:

Annuals of the Rose Society of Ontario

Two old men who sell electric fans

Anything, if you look at it the right way

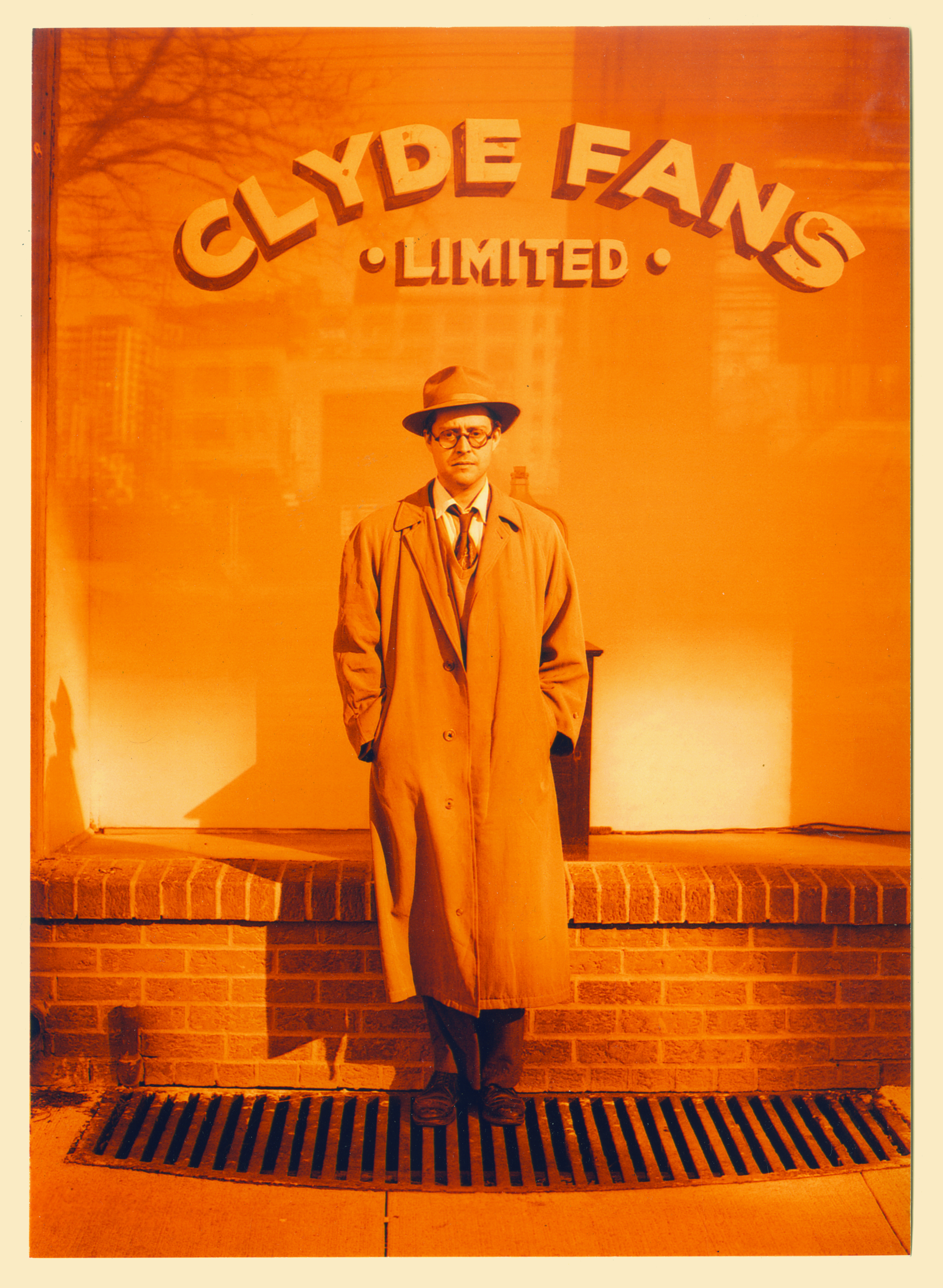

Twenty years ago, everyone was preparing for the end of the world by upgrading their computer software and wearing loose polyester pants that could literally be “torn off” in the event of some pantsless emergency. But Gregory Gallant, the artist known as Seth, was just beginning work on the graphic novel that would eventually become Clyde Fans—an ambitious melancholy, fictional history of a real, family-owned electric fan business. Set mostly in the 1950s, it is narrated by two brothers, the inheritors of the business, who struggle in different ways to make sense of the decline of a specific era of capitalism and, as a result, themselves.

If you know Seth’s work, it feels nothing other than extremely appropriate that, at a time when everyone was worrying about the future, he was looking towards the past. All of his comics and graphic novels are threaded thickly with nostalgia, from his cartoony 1950s drawing style, to his post-war settings and modernity-resistant characters.

But you won’t find anything sentimental or folksy about Seth’s work. He’s wary of romanticizing earlier eras, in a way that often leaves you pondering the strangeness of reality. Clyde Fans is no different. It is their very inability to adapt to change that kills the two brothers’ business—and sets at least one of them off on a mystical inward journey of self-discovery.

In some ways the book is the pinnacle of his thirty-plus year career so far, and contains all the hallmark “Seth” features we’ve come to know and love. Does it interrogate nostalgia? Check. Does it contain lots of Canadian memorabilia? Check. Does it describe the interior life of its characters more than a plot? Check. Does it delight in the mundanity of everyday existence rather than fantastical events? Check. Does it push the limits of what we expect from comics and stories in general? Check.

After twenty years of working on Clyde Fans on-and-off, however, Seth is embracing change. When talking to him over the phone last week, Seth admitted to me that Clyde Fans marks the end of a phase in his career—and he didn’t sound sad about it. What it means to create comics post-Clyde, he’s not quite sure. But he drops a few hints in our conversation below.

—Shannon Tien

I. Canadian Ephemera

THE BELIEVER: So what is it like to work on a book for twenty years?

SETH: It’s funny. I didn’t really think about it in those terms while I was working on it. I was certainly aware at some point that it was taking way too long. But initially, it was just a book that was supposed to take about five years. And then because of the way I was working—working on this, working on that, many different projects going—it started to take a lot longer than I anticipated.

So a couple of points. I felt dread when I looked at how long time had passed and at how much more I still had to do. I was like, “This is going to take a really long time” and I was both embarrassed and horrified that it wasn’t going to get done in any time soon. At around the ten year point I realized I still was barely halfway. So I think my main concern during this time was that I would not quit on it.

And I did feel that my thinking about how I do my work changed during this period too. Because when I started out, I had the idea that every project would have a deadline of five years or so. And then it would be done and you’d move on to the next one. And there was a kind of schedule the way that periodicals used to exist. But as time went on I started to think of myself more as an artist in the sense that I’m working on a variety of works and they’re a body of work. Not a publication in the true sense. And things will take the time they take.

So now when I think about Clyde, I realize it took a really long time, but in another way it just felt like a project I was working on while I was working on a lot of other projects.

BLVR: Do you think of yourself as someone who is committed to finishing what you start always?

S: Yeah I think so. I think the way my mind works—it might be a problem—is that I always plan things that are too ambitious. If I do a drawing, I think to myself, “I should do fifty of these.” Or I’m doing these paper cutouts I started a few years ago and I said to myself at first, “Oh, I’ll do a few of these and see if I enjoy them.” And then I was like, “Oh I like these. Let’s see if I can do fifty of them.” And then at fifty, which took no time at all, I was putting them into little portfolios, and each portfolio held about fifty drawings, and I said, “Well I’m going to do a hundred of these portfolios.”

So I’m at about the forty-fifth portfolio right now and I’m like, “I’m getting tired of these.” I think to myself, “Why did I plan that I have to do a hundred portfolios of them?” There’s always something in my mind that makes the project get bigger. So, with everything I’ve worked on, from my cardboard buildings to my comics, I always get a little too ambitious and then set myself up for failure.

But I do think that ultimately I really don’t like not doing what I planned.

BLVR: How do you know, generally, when something is finished? When you just feel like you can’t make anymore? Or you’ve done the thing you’ve set out to do?

S: Sometimes I feel like I’ve wrung everything out of it. That there’s nothing left. I kind of feel that with the paper cutouts at the moment. I kind of feel like I’m just doing the same thing over and over again.

I worked on this thing a few years ago where I decided to collect a lot of Canadian ephemera—like published pamphlets and books and stuff. And I wanted to study them and figure out what it was about them that appealed to me and what made them Canadian in my mind. So I spent about eight years gathering this stuff up and pasting them into books and writing about them, kind of expecting I would have some big epiphany of what it all meant. And it never really quite happened.

So, at the eight year point I said to myself, “This is done.” And the reason I knew it was done was just that I had nothing more to think about it. I feel like the last drop of whatever was in it has now been squeezed out.

BLVR: I like that analogy. So, what are the paper cutouts?

S: About three years ago I was looking at these paper cutouts of Hans Christian Anderson. When he would tell a story, he would fold a big piece of paper because he often told his stories to a crowd of people or an audience. And he had a big pair of scissors and he would just cut out an elaborate folded paper cutout while he was talking to them. And then at the end of his telling the fairytale, he would open it up, and it would be quite a beautiful and elaborate paper cutout.

But it was also really interesting because it was really bold and not finicky…It was actually very modern in the way it looked. It was just like “snip, snip, snip,” and then you’d open it up and there would be like–I don’t know—two mermaids and a tree. Very angular.

So this was very beautiful and I thought to myself, “I wonder how difficult that is.” So I started to take big pieces of paper and try to do essentially the same thing. Not try to be precious. Not plan things out. Just see if I could do like a negative space kind of drawing with cutting out paper.

What’s been interesting about it is that I think it’s changed my drawing. I think a lot more now in shapes and with negative space than I ever used to—and less with line. They seriously take like 5 or 6 minutes to do one. But it’s funny, I like to see things pile up, too. So it’s been valuable.

II. “ Even the most prosaic objects have a kind of power to them when you think of how you’ve carted them around for your life.”

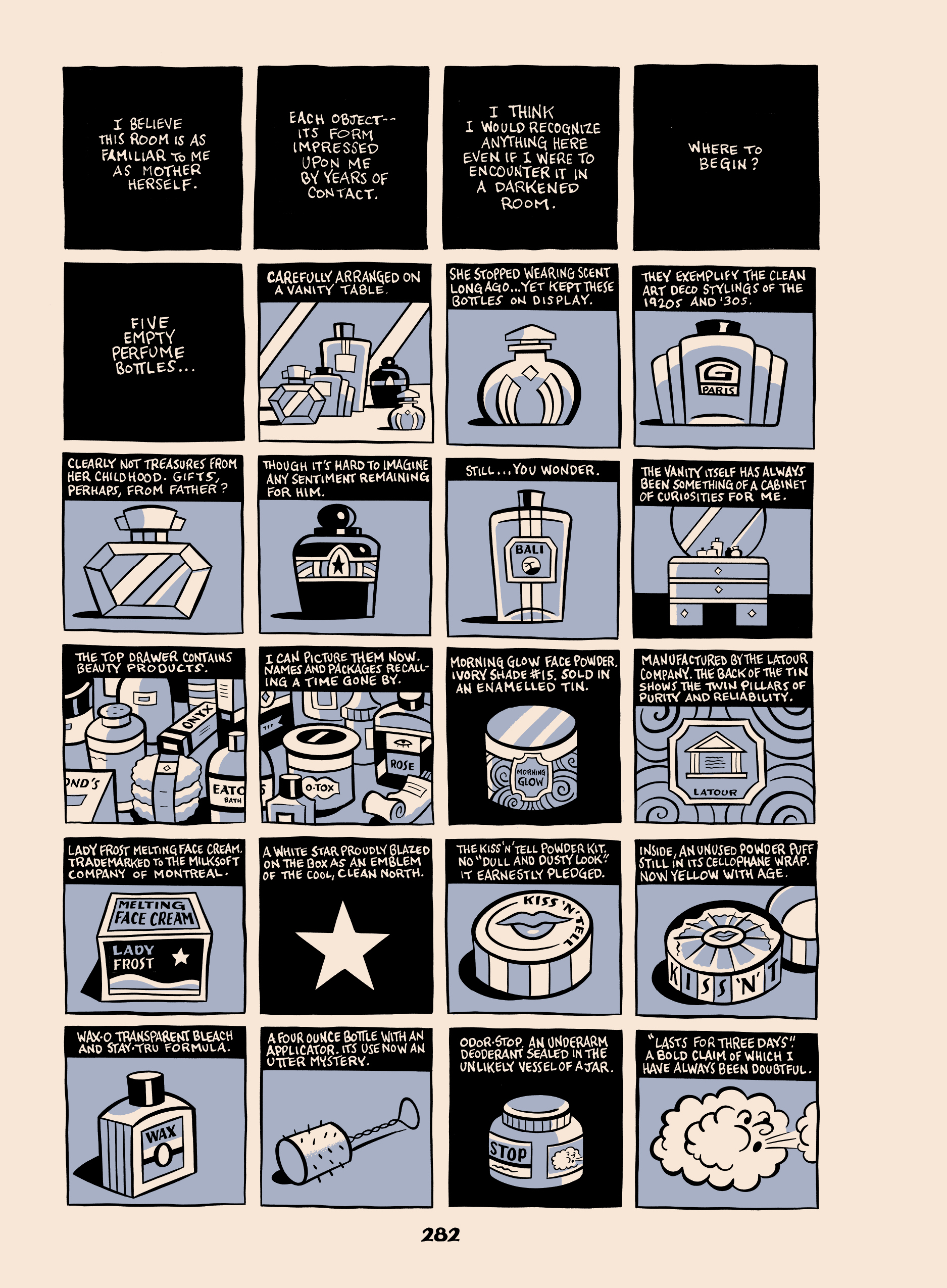

BLVR: Speaking of things piling up and all the Canadian memorabilia that you had collected, one section of Clyde Fans that I found really beautiful was the inventory of all the items in the mother’s bedroom. Can you tell me a little bit more about including those kind of items in your work?

S: I’ve always been really interested in objects. Sometimes I think I’m more interested in objects than I am in stories. There’s something about the description of things that is extremely appealing to me.

Eventually the more you write the more you come to question “What is a story?” Around the time I was working on that section of Clyde Fans I became more interested in the idea that a story doesn’t need to be all just about plot or about being concerned with the reader. I thought to myself, “I’d like to just talk about the objects in the room rather than draw them. They would be there anyway, but why not focus on them instead of just having them in the background detail?”

I thought I would experiment to see—and much of Clyde Fans is like this—how much you can do before the audience stops paying attention. I’ve heard a couple people say they really liked that section and I’ve read a couple people say that it went on two pages too long. So it’s hard to say. I wanted to really get into the idea that a life can be described by the things you own.

I’ve done this a few times in my work. To be honest I think the next couple of stories I’m going to work on are more description than they are plot.

BLVR: It’s a really interesting entrance into character, like how to tell the story of someone, or let the audience get to know them a little better—through the objects they collect.

S: It’s true.

BLVR: Now I’m just looking around at all the objects in my room. What do they say about me? [Laughing]

S: Yeah, it’s true. Sometimes I think it would be a perfectly sufficient story to just sit down and describe the things that are around you and where you acquired them. What they mean to you. Why you bothered to get them. I mean some of it would be pretty boring, but even the most prosaic objects have a kind of power to them when you think of how you’ve carted them around for your life.

BLVR: I used to work for a bookstore that sold weird memorabilia and they had a lot of art catalogs from the 50s. Auction catalogs for Sothebys and Christie’s. And they would sell for quite a lot of money. And I just found them to be a fascinating glimpse into “What were people really into in terms of art back then?” Or rich people, specifically. I’m not sure where I’m going with this, but it reminds me of that phase of my life.

S: Yeah I know what you mean. I’ve read a couple of books on auction houses and it’s pretty fascinating to see that weird shift of what is considered valuable in art.

S: Yeah I know what you mean. I’ve read a couple of books on auction houses and it’s pretty fascinating to see that weird shift of what is considered valuable in art.

BLVR: Exactly! And you can kind of glean some of that narrative from those catalogs.

S: For sure. A lot of things that are considered “boring” are really quite interesting. I’ve been looking at these annual books that came out from the Ontario Rose Society. They’re a horticultural society. But the book on the surface looks super boring. It’s just a bunch of pictures of roses and descriptions of meetings and listings of get togethers at nurseries and stuff. But as you read through it, it’s pretty easy to start constructing a whole world out of these speeches that you’re reading or the minutes of the readings. Suddenly characters are forming.

Clyde Fans I think was an example that I always joke about to people when they asked me what my book was about. I would say it’s about two old men who sell electric fans. That sounds so dull. But anything is interesting if you look at it from the right perspective.

BLVR: I totally agree. Speaking of Clyde Fans, I read in a couple of other interviews that the story idea also came from the physical world, like these two portraits that you saw inside a shop.

S: Yes, Clyde Fans really is inspired exactly by the real business Clyde Fans. It did exist in Toronto from the 50s to probably sometime in the 80s. Actually I don’t know the real history of it, but as an aside, I recently got an email from a guy who says he’s researched the company and going to send me all the information on it.

BLVR: Wow.

S: I actually kind of avoided learning anything about it while I was working on it, because I didn’t want it to influence the story I was writing. But basically that storefront that I use in the book is exactly like the real storefront. And I used to walk by it all the time.

But one day when I looked inside and saw the two photographs of two businessmen, black and white 60s portraits I started thinking, “Who were these men?” By the time I was ready to start Clyde Fans I’d pretty much figured out what the whole story was going to be. I certainly didn’t anticipate that I would work on it for decades, but I did have it figured out.

I wish I could see those portraits again because I’m sure they look nothing like the characters that I came up with.

BLVR: How are you feeling about finding out the so-called “real” history of Clyde Fans?

S: At first I almost thought maybe I shouldn’t see it. I wasn’t really 100% sure. But I figured the project is done now. It’s really done. So, I think I would be interested to see it.

I don’t think I’d be interested to meet anybody from the family or the company though. I think that would be weird. If there’s anybody left. I was always kind of amazed no one ever contacted me.

BLVR: How much did you have to learn about fans to write the book?

S: Well actually I only really read one book on electric fans. And that was a pretty minor education in fans. What I really had to learn about was salesmanship.

I didn’t want my knowledge of sales to be based only on “The Death of a Salesman,” so I bought a lot of books on salesmanship [published] in the 50s and 60s. But the one book that I bought at that time that turned out to be really great had a title like The 40 Best Sales I Ever Made. It was a series of articles by different salesmen telling the story of their most successful sale… and they were good stories, told well, unlike the other sales books which were just techniques on how to sell. And that was a book that I still own and I think I could still reread that just for pleasure.

BLVR: Nice. Has it ever come in handy to you in your real life? Have you ever had to sell something?

S: Not much. The funny thing is I don’t think I would enjoy being a salesman. It’s a very tough job. I always feel pity for telemarketers when they call me because I won’t talk to them, of course. That’s the really difficult part of sales is you gotta force people to listen to you and trick them basically.

I do think it’s a skill. And I’m not sure it is something you can learn. I think you do have to have a natural talent for communicating with people or for manipulating them—might be the better term.

III. “Language is a very poor way to communicate.”

BLVR: Do you often write about introverted characters in your work?

S: Yeah it’s funny, I’m not really an introverted person. I’m more of an extrovert by nature. But I value introversion. Most of my friends have been people who are more on the introvert scale than the extrovert scale. People get along easier in life I think as extraverts. But for myself, I find it one of my least appealing qualities. I much prefer being by myself and I’m less tortured when I’m by myself.

What I’m really interested in—maybe more than introversion—is actually the interior experience that everybody has, which is such a strange experience when you think about it. That we have an inner life that can’t really be shared with anyone else except through language. And language is a very poor way to communicate. It’s an approximation.

To some degree we’re so used to having an interior experience that we don’t give it a lot of thought. But, when you spend a lot of time alone, which I do in my studio, it does bring home to you how much of this idea of who you are is an interior construction of some sort. I think most of my work is about trying to write from that experience, to describe what the inner world is like. Or just about the strangeness of real life.

BLVR: Right, I can see that a lot—what you just described—in Simon’s part of the narrative of Clyde Fans. His inner life was so rich that it overtook the so-called “real world”… I really like that tension in your work because I’m always drawn to genre-bending literature that asks what is fiction and what is not fiction. And why is this a dichotomy that we keep insisting upon?

S: Yeah I know exactly what you mean.

BLVR: How do you play with that as an artist?

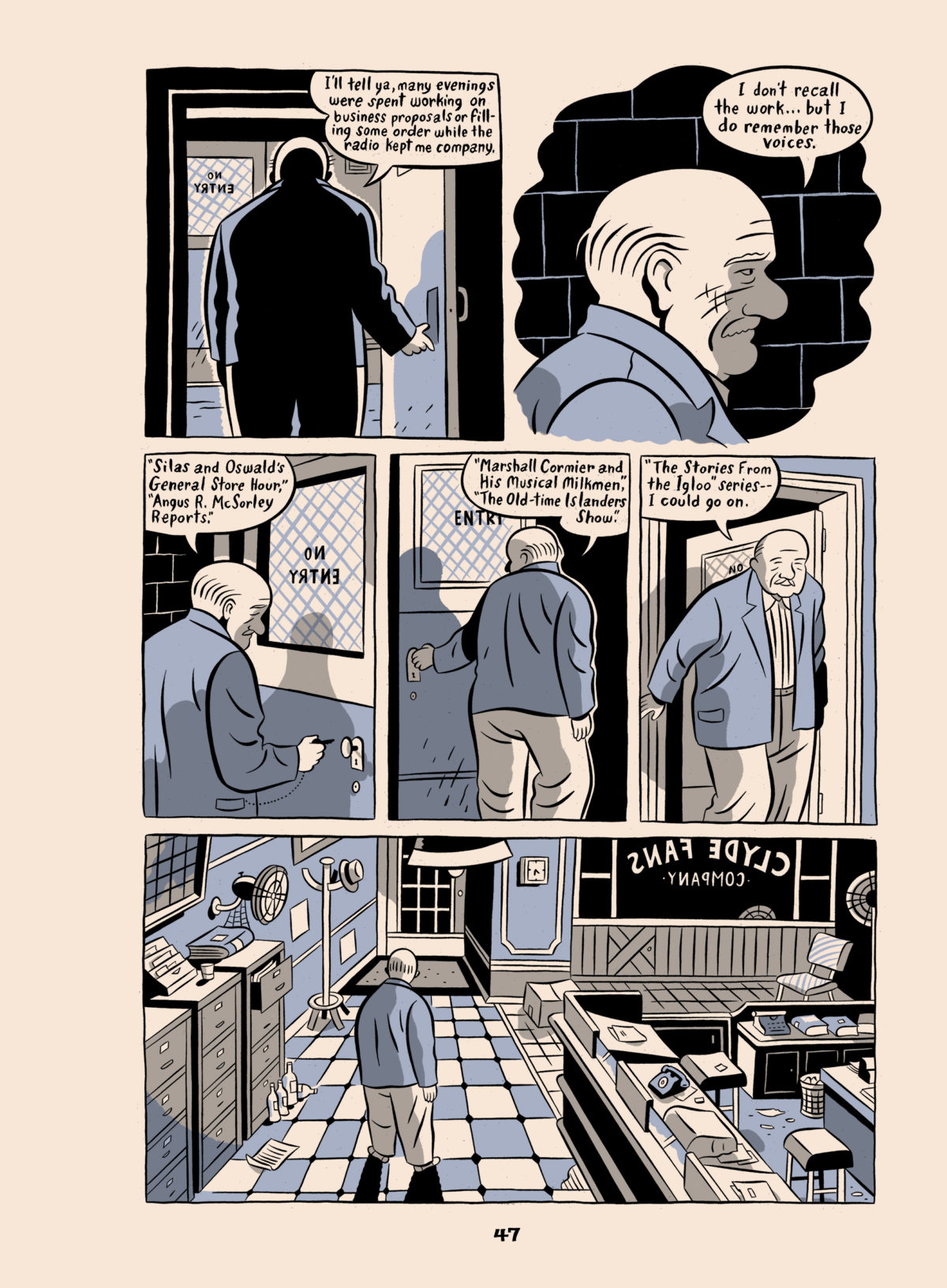

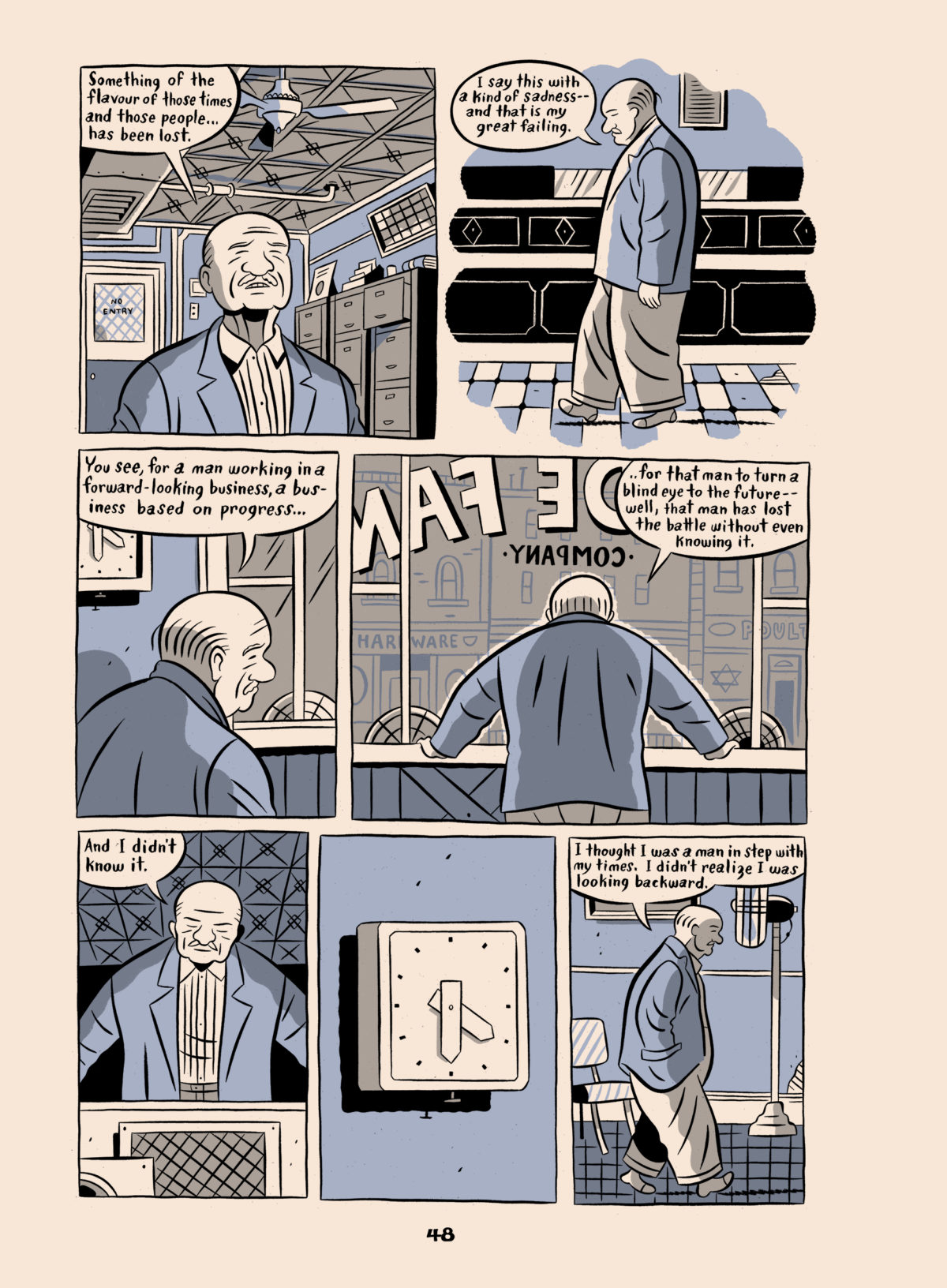

S: That’s a good question. So in Clyde I was trying to play with different ways of getting at the interior experience. At the beginning of the book there’s a very long monologue by Abraham and that was one way to try and talk about the interior experience. But later when you move into Chapter 3 with Simon, all the talking is in his head. I think it’s more trustworthy… What we talk about and what we feel, our interior experience and how we describe it, are very different things.

With Simon I was trying to create this slightly surreal world that he was involved in as well to put an edge on what was reality in the story and what wasn’t. There’s a few places in the book—and I won’t mention them specifically because I’ve left that for the reader—where I’ve made a few decisions that seem to say there is another reality going on in the book, a kind of mystic experience. I think a lot of it could just be Simon is mentally ill or he’s having hallucinations. But there’s another interpretation, which is that this is real.

So I didn’t want that to be fully determined, but I did want there to be a couple of points where you could point one way or the other to make a decision on it.

BLVR: Yeah I remember reading [in an online review of Clyde Fans] a description of Simon going through a breakdown by the end of the book and I was surprised. I was like, “That’s not what I thought happened at all!”

S: Good!

BLVR: But yeah, I think the set up of a fictional history of a real store is already so interesting and it pushes that idea of what we know to be reality from the start.

S: Yeah to some degree what was frustrating to me about Clyde was because I was working on it for so long, people had a certain idea of what the book was about and it wasn’t really accurate. And that was kind of my own fault.

People basically thought the book was about the mundane lives of two old men. And I knew that when I did the last chapter it would finally pull it together to have a much more mystic experience to it.

BLVR: Do you feel like that perception is changing now that everything is together in one volume?

S: Yeah I feel like it’s made a tremendous difference. It’s funny. I’d kind of given up on the book myself. When I finally finished it and put the package together of course I was glad it was done and I was proud of it as a book. But I was so used to the fact that no one ever paid any attention to Clyde Fans and hadn’t really talked about it to me in a decade that when it came out I wasn’t expecting anything.

Then I was a little surprised afterwards for people to start talking to me about it and I’ve done a lot of interviews since then and people have really looked deeply into it. They’ve read it. They’ve understood it. And it’s almost made me feel better about the book itself in the sense that now it’s not just something to cross off the list. I feel like people have paid enough attention now to recognize that it will probably be the biggest and most major book I ever do. I’ve kind of come back around to liking it again.

BLVR: Wow. How does it feel to be done the most major book you will probably ever do?

S: Good. There’s a certain sense in which that sounds like everything from here on in I will be less interested in or will be less ambitious. But I did learn working on Clyde that it might be better to focus on books that are only a couple of hundred pages long. And things that I can draw quicker.

I feel like a phase is over.

BLVR: If you had to pick, which of your books would you say you’re the most proud of so far?

S: It’s tough. When I say “proud” it’s like I’m glad I did them and I feel connected to them, but things quickly go into the past for me. So it’s a complicated answer.

Probably the book that I would put into most people’s hands would be George Sprott because that book is very focused. And I’m happy with how it came together. I don’t know that I would say it’s my best book or anything. I don’t really know what I feel about those kinds of thoughts.

BLVR: Interesting. That’s always hard to answer. I feel like whenever I’m done with a piece I often don’t like it anymore.

S: Yeah it’s pretty hard to look at your own work.

IV. “If anything seems interesting you should pursue it.”

BLVR: Did you grow up around other artists? How did you become a cartoonist?

S: No. I don’t think I ever met an artist until I was in art school. I grew up in small towns and my parents were not particularly interested in the arts. We only had a small amount of books and I feel like I grew up mostly interested in pop culture.

In the 70s when I was growing up there were really only three places where you would go for entertainment and that was television and the library and the news stand where you would buy magazines and comic books.

But it was sometime in the end of grade school when I became really interested in comic books and decided I’d be a cartoonist. Of course that meant I wanted to draw Spiderman or something like that. So I spent most of my teen years working hard on making my own little amateur comic books that were mostly superheroes and monsters.

I went to art school because I didn’t even know what to do when I got out of high school. It didn’t cross my mind to go to New York and try and get a job at Marvel Comics or anything. I figured you had to go to school. I really didn’t know much about art at all. And it was really art school that changed my life because in art school, even more than the teachers it was the other students that really changed my life. Going to see foreign films, getting interested in reading literature. Really learning about painting, photography, and all that stuff really changed my life and changed what I thought about comic books.

In the first year of art school I totally lost interest in the idea of drawing superhero comic books, but I still was interested in the idea of comic books. I was actually completely perplexed on what to do with a comic book if it wasn’t based on fantasy.

But I was lucky around that time that I discovered the work of R. Crumb and the underground comics and also that I discovered the work of the Hernandez Brothers. Those two influences really showed me that you could do comics about real life. And that really started me on a path towards the kind of cartoonist I eventually ended up as.

BLVR: Right. So speaking of false dichotomies, is this when you started thinking of comics as art?

S: Not immediately, but pretty quickly. When I think back on it now it was the beginning of me understanding even what art meant. With all that description of discovering film and literature and stuff, I’m still not sure I even really understood at that young age what I thought the purpose of this kind of work was. But I was responding to it really strongly.

Ultimately I came to understand the power of trying to use art to communicate what your life is about. And that took a long time to figure out. I came to realize that comics are a really good communicating tool for describing true life experience. And that in some ways they might be the best tools, even better than writing a novel—that combination of words and pictures is extremely powerful.

I got lucky in being seduced into being a cartoonist because if I’d grown up in a different kind of world I probably would have wanted to be a novelist or a painter or something that was considered more serious to begin with. And I might have missed out on working in such a great medium.

BLVR: What do you think the purpose of art is then?

S: Well it’s complicated. I’m not sure that there’s a simple answer to that question. But I do think one of the big powerful elements of it is art is something you use to define yourself.

It’s a way to express this deep quality of the inner self that is really a hard-to-define-thing, which is why I think it’s much easier to define the self through these indistinct forms than it would be to try to directly use the self as an art form. So by writing stories, by making music, by drawing pictures, we’re somehow taking this totally complicated interior experience and presenting to people through a mask.

Whenever I’m working on a project I never worry about what it means or what I’m trying to say because I think that just slows you down. That’s something you figure out later. If anything seems interesting you should pursue it. I was just reading a quote from Claes Oldenburg where he said that an artist has to have the confidence to follow a stupid idea to its logical conclusion. I think that’s very true.

BLVR: Right. Yeah that’s so hard. Coming from an academic background I’m always like, “What does this mean? What am I trying to say?”

S: No absolutely.

BLVR: But I agree. You definitely have to let go of it for a moment, at least.

S: I think so. It’s funny though that like you said academia or art school is like that too. You’re constantly being put in the position of having to explain what it’s all about. And in some ways I think that’s a terrible mistake.

BLVR: You’ve written compellingly about nostalgia a lot, the dangers of falling into it, not resisting it, etc. Which era would you say you’re most personally nostalgic for?

S: Well when I was younger I probably would have said that I felt deeply attracted to the mid 20th century, the 40s and the 50s. Maybe even back to the 20s. But as I get older, much like almost anybody, the real nostalgia I feel is for my own childhood era, for the 1970s and the 1960s. Even though I don’t think they’re the most beautiful of eras aesthetically compared to the other eras I was interested in.

I consciously calculated my drawing style when I was younger and it was mostly based on works from the 1930s to the end of the 1950s. But I’d say the 50s strangely is probably where its clearest where my influence comes from. And I don’t even think about it any longer. When I sit down to draw something I don’t think to myself, “I’m trying to make this look old fashioned.” Now it’s just a drawing style. But I am sometimes aware that I’m not including any contemporary details.

BLVR: I like that. I’m not not trying to be old fashioned.