“I’m a spirit master,” avant-garde jazz composer and bandleader Sun Ra once said in his own inimitable fashion. “I’ve been to a zone where there is no air, no light, no sound, no life, no death, nothing. There’s five billion people on this planet, all out of tune. I’ve got to raise their consciousness, tell them about the wonderful potential to bypass death.”

For four decades, from the early fifties until his death in 1993, Sun Ra and his Arkestra baffled, dazzled and aggravated jazz fans with an uncompromising and unpredictable musical style that wandered the spectrum from finger-popping bebop to the harshest of atonal free jazz (sometimes in the same piece), and a mythology that often kept audiences off-balance and guessing. Sun Ra didn’t sell many records in his lifetime, but along with the Arkestra, he nevertheless became the stuff of legend.

The artist who would adopt the name Sun Ra was born Herman P. Blount in Birmingham, Alabama in 1914. Raised mostly by his grandmother and an aunt, Sonny, as he was called, with very little formal training, taught himself to read music and play piano. The first major hint that Sonny was headed in his own singular and mystical direction came while attending Alabama A&M, where he began to tell people he’d been abducted by aliens. The extraterrestrials, he said, returned him to Earth with a mission to save mankind and bring peace to the world. Although the details of the story, as well as which specific humans he’d been charged with saving, would evolve over the next several decades, the core idea that he was not completely of this earth would remain at the heart of his persona until his death.

He dropped out of college in the early 1940s and moved to Chicago, where, under the name Sonny Blount, he began playing piano with a number of small jazz outfits around town. His unique, often puzzling and cryptic version of jazz lingo, as well as a musical style that pushed far beyond the standard bebop parameters of the era, led his fellow musicians to dub him “Moon Man.”

Around 1953, having by then adopted the name Le Sony’r Ra, he began to pull together the ensemble that would eventually coalesce into the Arkestra. Shortly after being discharged from the Army, tenor saxophonist John Gilmore joined the fledgling band. Fellow sax players Pat Patrick and Marshall Allen also joined around that time, and all three would remain central figures in the Arkestra for the next four decades.

The Arkestra featured over a dozen musicians by 1955, and Sun Ra finally settled on the name that would follow him for the rest of his life. A small, moonfaced man who spoke in enigmatic riddles, he fully inhabited the persona of a science fiction jazz Buddha. Sun Ra now claimed he had been born on Saturn, and had come to Earth to offer a message of peace and salvation through music, as well as hope for a better life elsewhere in the universe.

“Somewhere in the other side of nowhere is a place in space beyond time where the Gods of mythology dwell,” Ra said. “These gods dwell in their mythocracies as opposed to your theocracies, democracies, and monocracies. They dwell in a magic world. These Gods can even offer you immortality.”

Ra’s compositions grew more eclectic and adventurous, moving deep into uncharted sonic territories. He and the Arkestra settled in New York’s Lower East Side, hoping to crack into the city’s more radical jazz scene. Several years before Miles Davis’ game-changing Bitches Brew, however, the Arkestra’s often impenetrable atonal experimentation scared off even the most boho jazz fans and critics, and the band remained in obscurity. In the late sixties they relocated to Germantown in Philadelphia.

Although Sun Ra himself insisted they moved because his mission on the planet required he go to the worst place on earth in order to save it, the more likely explanation is that he and the Arkestra had been evicted from their place on the Lower East Side, and Marshall Allen’s father had given them a rowhouse in the West Philadelphia neighborhood.

Saturn House, as it was dubbed, became the site of almost round-the-clock rehearsing and recording, with Sun Ra overseeing things like a cult leader. Having split from the Nation of Islam but remaining a staunch believer in black empowerment, he refused to hire white musicians or women (a strict rule he broke later when he brought in vocalist June Tyson in 1968). He also forbade members of the Arkestra from drinking, smoking, using drugs or cavorting with women. Despite the strict rules and the fact they were paid little or nothing, most of the musicians stayed on, as they fully believed in Ra’s mission.

With the help of his long-time business manager Alton Abraham, Sun Ra created his own record label in 1956, Saturn, to release Arkestra recordings. The albums, which were usually pressed in very small batches, were sold exclusively at live shows and through a tiny smattering of hand-picked record stores. “Stuff from three different years and three different sessions would appear on a record,” Jerry Gordon, co-founder of Evidence music, told journalist Mike Walsh in 1993. “Almost always the records listed the wrong personnel. Some had no titles, no dates, no documentation. Everything to do with his label was confused, and I believe it was intentionally confused.” Over the years Sun Ra would release over a hundred albums on Saturn.

Arkestra recordings were also licensed and sub-licensed by a number of labels around the globe, including Savoy, Transition and, perhaps most notoriously, Bernard Stollman’s ESP-Disk. Since the time of Sun Ra’s death a number of other labels including Evidence, El Ra Records, Art Yard, Atavistic, Scorpio, Transparency, and Universe, began releasing Sun Ra recordings. Some, like Evidence, were legitimate, others less so.

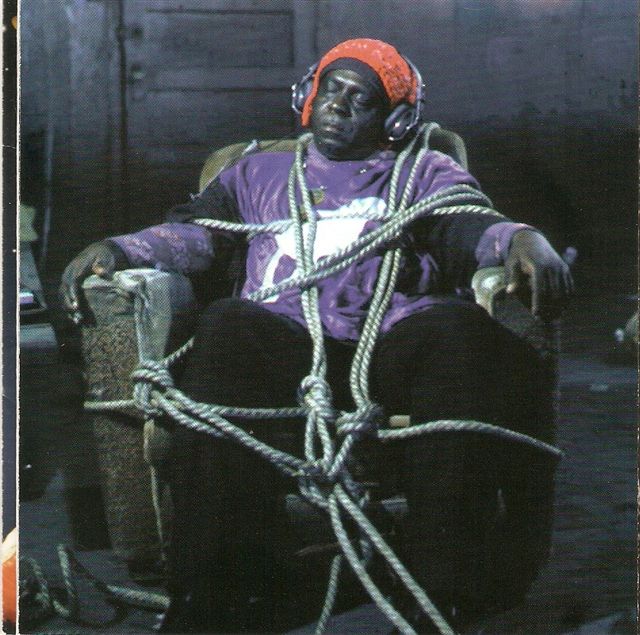

The Arkestra became a reflection of Sun Ra’s mythology. Live performances became outrageous spectacles, marked by elaborate sci-fi costumes and headgear, acrobatics and extravagant light shows. Performances, some thought, took precedence over the music, and more mainstream jazz aficionados and critics tended to dismiss Sun Ra as less a composer than an eccentric showman. As far as jazz composition is concerned, however, nowadays most critics agree Sun Ra was decades ahead of his time, and remains there to this day.

In 1976, then-sixteen-year-old Michael Anderson was hosting a Big Band show on Temple University’s radio station when a friend suggested he get in touch with Sun Ra. “I was playing him, but had no idea he was listening to my show,” Anderson says. “This guy said, ‘Look him up—he’s in the phone book.’ So I called, and we ended up talking for hours.”

After the call, Sun Ra invited Anderson, who’d been drumming since he was five, to join the Arkestra. Anderson moved into Saturn House, becoming the Arkestra’s youngest percussionist.

“It was beautiful,” he says. “A real communal atmosphere. At college I was used to living with people from all over the world, so it was no big deal. See, I knew the music where Sunny’d come from. I knew the history. A lot of these musicians didn’t know the music. I brought Sunny a bunch of records, which he later transcribed.”

The product of a deeply troubled and abusive childhood, Anderson left home when he was fifteen. The move into Saturn House, he says, was a godsend. “It gave me direction. Way I was going, angry as I was, I might well have ended up in prison. Sunny pretty much adopted me, becoming a real father figure. The other musicians were like uncles.”

After rooming with Marshall Allen for a bit, Anderson says Sun Ra eventually invited him into his room. “He told me to familiarize myself with the [Arkestra’s] music. I was listening to My Brother The Wind, Vol. 2, when I started looking around. The room was full of tapes. There were tapes everywhere, and it was a mess. A lot of them were unspooled, and they were stacked six feet high. So I started straightening things up and putting them in order. When Sunny came in and saw what I’d done, he was very happy I’d taken the initiative. Later someone came in and messed things up, and Sunny got really mad at me. He said, ‘You’re supposed to take care of this—you’re the archivist.’ I had no idea I was the archivist.”

Anderson left the Arkestra in 1983 to take another radio job in New York. “I was on the radio at the same time I was drumming,” he says. “I was the only one who was playing him on the radio. You don’t hear Sun Ra on NPR.”

Anderson stayed in touch after leaving the band. While helping care for Sun Ra after a series of strokes in 1992, “[Sunny] made a gesture. He couldn’t speak anymore, but I knew he was telling me to take care of the tapes. Someone had been stealing them. I didn’t want anyone to think it was me. I’d been working with Alton [Abraham], so first thing I did was send some to him for safekeeping. When I told Sunny, he got really angry and pounded the bed. I wasn’t supposed to do that. He and Sunny had had that big split in the Seventies over Space is the Place.”

Anderson packed up most of the tapes and has been at work archiving the contents ever since. “I’ve been listening to them for over twenty years now, and I’m only up to the 1970s,” he says.

From the start the idea had been to release the material in order to get the music out into the world and keep Sun Ra’s legacy alive. “I have things here no one’s ever heard. I have outtakes and false starts. I have the original stereo masters that were mixed down to mono. The stereo masters don’t have that distortion. I was telling Jerry Gordon at Evidence that he released a track that was three and a half minutes long, but I had the original, which runs over six minutes.”

Apart from the technical aspects, there were all the legal issues at play. Digitizing, remastering, and releasing all that material was a monumental task far beyond Anderson alone.

Which brings us to Irwin Chusid, preservationist. Veteran champion of outsider artists, and host of his own long-running show on Jersey City-based freeform radio station WFMU. In the past he had single-handedly introduced the work of Raymond Scott and Esquivel to a new generation, and now as administrator of Sun Ra LLC, he’s poised to do the same for Sun Ra.

Chusid admits that despite all his years in the business, he never fully appreciated the vast scope of Sun Ra’s output until recently. When he first met Michael Anderson some twenty years ago, he had no idea Anderson had been a percussionist with the Arkestra, nor that he was in possession of the tape archives.

“I met Michael when he arrived at WFMU to enlist as a DJ in the early 1990s,” Chusid explains. “We hit it off immediately by our shared love of Raymond Scott’s music and old school R&B. His music offerings were eclectic and unpredictable. I recognized a kindred free-form radio spirit. On an overnight shift, he once played an hour of Grand Funk Railroad live, followed by an hour of bebop. We became and remain great friends. I have tremendous respect and affection for Michael, who has lived a precarious life preserving the Sun Ra session tapes.”

In the fall of 2013, Anderson contacted Chusid in hopes of enlisting his help on the project.

“He was having financial and health issues, and was owed money by a number of labels,” Chusid says. “He put me in touch with Thomas Jenkins, Jr., Sun Ra’s nephew and managing member of Sun Ra LLC, comprised of the heirs of Ra. Some fans seem surprised that Ra had an earthly family, and that his descendants were lawfully entitled to inherit his rights. Ra remained in contact with his sister Mary Jenkins—Thomas Jr. is her son—and there was great affection between the two. This extended to various nieces and nephews. These exchanges were kept out of the public spotlight, but Mary was always proud of the musician she referred to as ‘her “little brother Sunny.’ When Ra needed money, he occasionally turned to Mary. After Sun Ra suffered strokes in 1992 and the Arkestra members in Philadelphia could no longer manage caretaking for him, they sent him by train down to Birmingham, where he was looked after by his family. He passed in May 1993 without leaving a will. It took five years to settle the estate, but the Probate Court of Jefferson County decreed that there were lawful heirs who inherited the rights to the recordings, writings, publishing, contracts, and any outstanding royalty streams. And the house in Philadelphia.”

The Sun Ra estate, established at that point and overseen by Ra’s niece Marie Holston, was dissolved in 1999 and eventually replaced by Sun Ra LLC with Jenkins in charge.

“Thomas—a man I love and admire for his diligence, humor, and strength of character—explained to me the parade of unscrupulous characters who, after Ra’s departure, emerged from the shadows to assert rights without lawful claims,” Chusid says. “Jenkins provided conclusive, documented proof of chain-of-title on Ra’s rights for Sun Ra LLC, as well as a chronicle of dubious, and in some cases provably fraudulent, claims by those who felt entitled to a financial stake in Sunny’s artistic legacy. And when I say financial stake, I should add, such as it was. Ra died impoverished, and owed the IRS—are you ready?—$146,799.95.”

After investigating, the IRS declared the debt “uncollectible” and dropped their claim. “During Ra’s life he never made much money on his music,” says Chusid. “People like ESP-Disk’s Bernard Stollman made sure Sunny’s heirs never made much on it either.”

“There are people sitting in jail now who are collecting royalties that should be going to the band and the project,” Anderson says. “There are snakes everywhere. Even inside the organization.”

One of the figures who attempted to claim a chunk of the Sun Ra empire was his long-time business manager, Alton Abraham.

Despite having gone through a contentious split with Ra in the Seventies, “Abraham tried twice in court during the 1990s to claim administrative rights over the estate,” Chusid says. “However, he couldn’t produce a single document proving an active business partnership with Sun Ra at the time of the latter’s death. Judicial decrees were issued denying his claims. That said, anyone who knows the history of Sun Ra acknowledges that without Alton Abraham, the world might never have known about Sun Ra, whose career might not have progressed beyond the strip clubs of Calumet City. They went through a nasty professional divorce, and Sunny ended up owning the store. It was, after all, his music.”

After his death in 1999, most of Abraham’s belongings—including his own extensive private archive of Sun Ra material—were unceremoniously tossed into a dumpster. The archive was salvaged, the story goes, by Ra researcher John Corbett, who then donated it to the University of Chicago.

“They just went in and demolished Alton’s house,” Anderson says. “And after that these boxes of tapes started showing up on my doorstep.”

Seriously complicating matters is the level of contention Anderson perceives between himself and Sun Ra’s heirs. “The nephew won’t talk to me,” he says. “No one in the family will deal with me. I brought Corbett in to help with the project, but then he went over to their side. I worked to get some of the musicians paid, but nobody notices that. I’ve done all this shit, but they continue to deny me. They even claim I was never a member of the band. They point to the discography, but the discography is so incomplete it’s crazy. They may have all the records, but I have the masters. They never lived in the house. I did. But they keep denying me.”

(For the record, it should be noted that Thomas Jenkins has in fact remained in contact with Anderson.)

At the heart of the matter, Anderson believes, is racism. “People have actually said to me, ‘What do you plan on doing with the tapes?’ It’s just that old idea, right, that niggers can’t do shit. I was at Sirius radio from the beginning. I helped develop the technology that made Sirius possible. I judge people by their character, not the color of their skin. Why can’t people get beyond that? I’m just doing what I can to keep this music alive and get it out there.”

Chusid admits he had no idea what he was getting himself into when he agreed to step inside Sun Ra’s universe to try and sort a few things out. “I did it to help Michael, because he asked,” he says in retrospect. “I did not comprehend the scope of the task ahead and had no idea where it would lead. To be honest, I foresaw a tremendous expenditure of time and labor without any prospect of making it profitable. Just about every project I’ve developed—Raymond Scott, Esquivel, Jim Flora, Langley Schools, Shooby Taylor, outsider music—started as a labor of love, a challenge, something that intrigued me, and that was grounded on a unique artistic legacy that appealed to me. It was that way with Sun Ra. He’s one of the great, unsung musical geniuses of the 20th century—easily dismissed as a crackpot or a charlatan by those who barely know his music. And if all you know is ‘Space is the Place’, you don’t know his music.”

One of the immediate problems, Chusid saw, was the fact that, though Anderson owned all the tapes, he didn’t own the music recorded on those tapes.“That’s when I reached out to Ra’s heirs.” It was agreed by all the involved parties that Chusid would officially become Sun Ra LLC’s administrator, handling all their business affairs.

“I then set about defending their respective interests, which involved going after numerous malefactors. I put my own money on the line—paid the attorneys’ fees. Yes, that’s attorneys, plural. And we prevailed. But I would be ungracious if I didn’t acknowledge the help and support I received from the “Ra professoriate”: Robert Campbell, Christopher Trent, Peter Dennett of Art Yard, John Szwed, Paul Griffiths, Hartmut Geerken, John Corbett, Craig Koon, Howard Rosen, Christopher Eddy, and others. These guys were orbiting the cosmos with Ra decades before I came along. They taught me a lot.”

Chusid also discovered that despite the deliberately confounding and misleading nature of so many of the Saturn releases, in business terms, Sun Ra knew what he was doing.

“Ra knew he was dependent on his copyrights for income,” he says. “But he left a large part of the number-crunching and contractual arrangements to Alton Abraham and others. They did register his compositions with the Library of Congress Copyright Office, and—this is something of a miracle—Ra retained ownership of his publishing, under Enterplanetary Koncepts (a BMI-affiliated entity), and the rights to most of his master recordings, including everything on his Saturn label. So his heirs inherited a huge catalog of recordings and compositions. I’d estimate that Ra retained rights to ninety-eight percent of his publishing, and ninety percent of his recordings. Most artists sign those things away for a pittance. Ra didn’t—whether from distrust of music industry predators, a sense of pride in ownership, or a combination thereof. That both sides of the rights were owned by one party simplified my job immensely. And when I say ‘simplified,’ I should add, ‘such as it is.’ It’s been anything but simple.”

Making his job a bit more complicated still, a number of recording projects were off the books, cash-only deals.

“Contracts were signed, then disappeared. Or maybe there were no contracts to begin with. Misinformation was circulated—sometimes by Ra himself. He was part-sorcerer, part-jester—Mystery, Mister Ra—and seemed determined to inflict sleepless nights on historians trying to pin down dates, recording venues, personnel, and accurate titles.”

“Ra was analogous to a five-tool ballplayer, unconcerned about the leaderboards, who says to the statisticians, ‘I’ll hit ’em, you guys count ’em.’ There were a number of lingering outside claims that had to be resolved, including ownership of masters on other labels, and one pestilential and deluded miscreant in Europe who continues to attempt to claim Ra’s publishing despite a total absence of authority.”

Of all the villains attempting to lay claim to Sun Ra’s legacy, few were more widely storied or despised than ESP-Disk’s Bernard Stollman. Founding the label in Brooklyn in 1964, Stollman originally envisioned ESP-Disk would release albums exclusively in Esperanto. As those were relatively rare, and given Esperanto never really took off as the international language it was intended to be, he soon branched out. ESP quickly established itself as the premiere label for free jazz and underground rock, with a catalog that included Ornette Coleman, The Fugs, and The Godz.

Stollman, who seemed at least somewhat earnest, prided himself on allowing artists on his label full creative control over what appeared on their albums. In exchange for that freedom, he held onto the universal rights to their work and rarely if ever paid any of them a dime.

“Stollman issued two historic albums by Sun Ra in 1965—The Heliocentric Worlds of Sun Ra, volumes 1 and 2—and two live albums in the 1970s,” Chusid explains. “So he knew Sunny and released some of his recordings, but it’s open to debate whether Ra ever fully trusted him. I can’t address Stollman’s business practices regarding other artists. I can only speak from my own experiences: I found the man crazy, creepy, and vulturous. He tried for years to get the Ra heirs to allow him to represent the estate, but they rejected him each time. So in 2001 he drafted a clumsily worded one-page “notice of retainer,” got a relative of Ra to sign, and with this bogus document managed to convince a number of foreign sub-publishers, record labels, and performing rights organizations that he was the legit administrator. He pocketed all foreign and some domestic revenue for 13 years. We’ll never know how much he siphoned off. Talking to him on the phone was Kafkaesque. I’d ask a simple question like, ‘Bernard, where’s the money?’ In response he’d offer an evasion followed by a dodge, which transitioned to a non sequitur followed by an anecdote and a digression, then a remembrance, a philosophical observation, and another non sequitur. He’d continue in this dizzying manner for fifteen minutes, after which you’d realize he never answered the original question. So I threw him to the lawyers. When we forced him to relinquish his claims in late 2014, he paid a token sum. He died three months later.”

Part of the tension between Sun Ra’s heirs and Anderson may arise from the fact Anderson had not only worked with Alton Abraham, but also worked with Stollman at ESP from 2004 to 2013.

“I don’t think the nephew trusts me because I worked with Bernard. But I didn’t steal any of Sunny’s money. Bernard asked me to give him the tapes, but I wouldn’t do it. They didn’t belong to him. I didn’t just work with Sunny there, I worked with everyone on ESP. I had to put up with [Stollman’s] shit all that time. Again, I think it was racism. But when someone messes with me, they’re gonna get hurt. When Bernard fucked me over, that’s when he started getting sick. And now he’s dead.”

To put Anderson, Chusid, and Sun Ra LLC’s task in perspective, in 2000, researchers Robert L. Campbell and Christopher Trent published the second edition of a discography, The Earthly Recordings of Sun Ra. The book runs over eight hundred pages and contains 788 individual entries. Seventeen years later, the pair has amassed enough new and revised material that any third edition would run an estimated 1200 pages.

Which goes to show how invaluable Anderson’s methodical, if quixotic, cataloging of the archived tapes has been to the entire enterprise. Having been on the scene in Saturn House, he not only knows what pieces he’s hearing and when they were recorded, but the historical context and the back stories of those involved, both official Arkestra members and otherwise. Some of this he has compiled on a computer database, some on paper, but most of it remains in his head alone. He’s understandably extremely protective of the tapes, which are presently maintained in less than ideal conditions at his suburban New Jersey apartment. As Chusid puts it, “Anderson doesn’t have a job, he has a commitment.”

With the rights issues for the most part properly corralled at last, Chusid, Anderson and Sun Ra LLC have now shifted their focus to upgrading the recordings and once again making them commercially available to a new audience.

“The Evidence label—Howard Rosen and Jerry Gordon—performed a noble mission in the 1990s preserving Ra’s music and introducing it to new generations on CD,” Chusid says. “If not for their efforts, would we even be having this conversation? However, the Evidence reissues were produced during the early days of digital restoration, and they didn’t always have access to best-source audio. They worked with what they could find. We have access to a wider range of source material — Michael’s tapes and vintage Saturn LPs from our extensive network of Ra collectors, who have been very generous in sharing material.”

In 2014, Anderson digitized some two dozen classic Sun Ra recordings and Chusid remastered them, posting the collection on iTunes. To date they have posted sixty digital releases on the Enterplanetary Koncepts label, available at all digital retail platforms, and at present they’re in the process of expanding the project, with a slew of upcoming official reissues.

“We’ve partnered with two labels,” Chusid says. “Modern Harmonic, a Sundazed spinoff, and Strut, based in the UK, and have released a number of successful collections, with more in the pipeline. We’ve also set up a pressing and distribution deal with Virtual Label, through whom we will be reissuing a classic Saturn catalog on our new imprint, Cosmic Myth Records. There will be previously unreleased bonus material, and new liner notes and graphics. Ben Young and Joe Lizzi, working closely with Michael, are handling the transfers and remastering, and we’ve got authorities like Christopher Trent, Brian Kehew, and others penning historical chronicles about these reissues. The first two releases on Cosmic Myth will be 1965’s The Magic City, a transitional album for Ra, and 1970’s Moog-centric My Brother the Wind, Vol. 1, in a 2-LP expanded edition. Both have never sounded crisper, or had such extensive annotation.”

He does warn, however, that modern listeners shouldn’t dive in expecting the same kind of flawless crystalline sheen that marks so many contemporary digital remasterings. “There’s only so much you can do to improve most Ra recordings. His catalog—indeed his style—is redolent with wrong notes, indifferent mixes, ad hoc mic placement, ill-tuned instruments, distortion, and dollar-store acoustics. Ra never recorded in a Dave Brubeck studio with a Miles Davis budget. Searching for perfection in Ra is a fool’s errand. With Sun Ra, it’s all perfectly flawed. But where it lacks sonic purity, it offers something more gratifying: soul.”

In a way, the struggles undertaken by Chusid, Anderson, and Sun Ra’s heirs have made large strides toward offering the singular composer the immortality that was always such a central tenet of his space age philosophy.

Jim Knipfel is the author of Slackjaw, These Children Who Come at You with Knives, The Blow-Off, and several other books, most recently Residue (Red Hen Press, 2015). his work has appeared in New York Press, the Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice and dozens of other publications.