“And it was then that fear, and with fear serious reflection, began.”

—Albert Camus,The Plague

What have you done as COVID-19 spread—first slowly, and then very, very fast—across the United States, shutting down theatres and professional sports leagues, businesses and schools and universities, driving us into our homes? I’ve turned, as is my tendency, to books. My wife and I had already laid in stores (“I went and bought two Sacks of Meal,” notes Daniel Defoe in A Journal of the Plague Year, “… also I bought Malt, and brew’d as much beer as all the Casks I had would hold,”) and shut down all but the most essential face-to-face encounters. Time loomed before us, like it always does, as a question mark. “There was a serene blue sky flooded with golden light each morning,” Albert Camus observes in his novel The Plague, “with sometimes a drone of planes in the rising heat—all seemed well with the world. And yet within four days the fever had made four startling strides: sixteen deaths, twenty-four, twenty-eight, and thirty-two.”

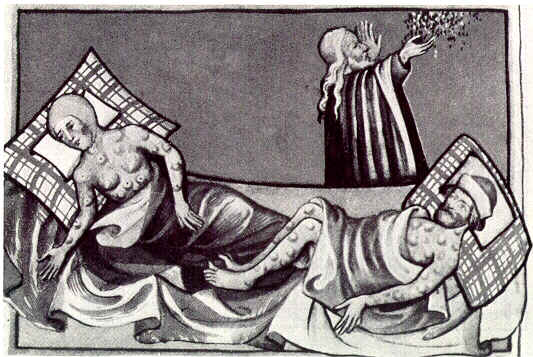

The Plague was Camus’ second novel, published in 1947, not long after the end of the Second World War. It has long been considered an allegory referring to the Nazi occupation of France (as well as the ensuing French Resistance), yet while I don’t dispute that, it is not what I am looking for. What interests me, instead, is the experience of reading the novel in the midst of an equivalent situation, as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds. The Plague is just a single example; the literature of pestilence, of contagion, is rich, going back hundreds, if not thousands, of years. I think of Boccaccio’s Decameron, composed in the 1350s, a confluence of stories shared by ten young people who flee Florence during the Black Death epidemic of 1348 and isolate themselves in a villa outside the city for two weeks. I think of John Edgar Wideman’s The Cattle Killing, with its core narrative about the 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic in Philadelphia: “[c]ircles within circles,” Wideman writes. “Expanding and contracting at once.” I think of A Journal of the Plague Year, an account of the 1665-1666 London plague that killed 100,000. Defoe survived that epidemic as a child—he was born in 1660—although his book, published in 1722, is fiction as opposed to autobiography. What this suggests is that, even if art cannot ultimately save us, our humanity depends on its expression just the same.

Something similar might be said about The Plague, which Camus began writing in the early 1940s, before the outcome of the war was clear. This is a key point, for it requires that his focus, much like Defoe’s, is not on how we die under duress but how we live. Taking place in the Algerian port city of Oran, the novel unfolds in the 1940s and involves an outbreak of bubonic and pneumonic plague. At first, neither the authorities nor the populace are worried; later, they downplay their fears. “In this respect,” Camus writes, “our townsfolk were like everybody else, wrapped up in themselves; in other words they were humanists: they disbelieved in pestilences.” The culture he’s describing is not unlike ours, with its cars and public transport, its shipping and newspapers and hospitals, a society in which modern technology, modern medicine, have seemingly rendered the risk of mass contagion obsolete. This is among the most terrifying and compelling aspects of the novel, that it takes place not at a historical distance but in a world recognizably similar to this one. As the plague spreads, all those familiar structures quickly reach the point of crumbling, stressed to the verge of collapse. “A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure,” Camus continues; “therefore we tell ourselves that pestilence is a mere bogy of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away. But it doesn’t always pass away and, from one bad dream to another, it is men who pass away, and the humanists first of all, because they haven’t taken their precautions.”

This is quintessential Camus: a case for the absurdity of human arrogance in the face of an indifferent universe. The first time I encountered the novel, it was with a deep appreciation of its humor, as embodied by, say, Grand, a middle-aged ascetic, who writes and rewrites the first sentence of his magnum opus, trying to make it perfect, or Tarrou, a kind of existential penitent, who seeks discomfort so he will be aware of every second as it passes, and, thus, not “waste” his time. Still, if I am tempted to read it through a different lens now, such absurdities remain at its heart. On the one hand,both Grand and Tarrou are punchlines, so extreme in their pursuit of the engaged that that become parodies of themselves. On the other, it’s impossible, in this moment, not to recognize that they want the same thing we do: to live a life of meaning, however that may be defined. The desire doesn’t evaporate in a time of pandemic; in fact, it may become more profound. Regardless, Camus is not only pointing out the absurdities of our cosmic situation, he is arguing, always, for humility and love. In his essay The Myth of Sisyphus, he frames this in the most personal terms: “Happiness and the absurd are two sons of the same earth. They are inseparable.” What he’s saying is: meaning is what we make it. We must be responsible for ourselves. The implication is “that all is not, has not been, exhausted. It drives out of this world a god who had come into with dissatisfaction and futile sufferings. It makes of fate a human matter, which must be settled among men.”

Ultimately, such a statement applies equally to everyone, the characters in The Plague as much as those of us outside the book. We do not get to choose our times, our circumstance. All we can choose is how we live. “What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men to rise about themselves,” the novel’s protagonist, a physician named Rieux, insists… correctly, I believe. We must look for a way to go on. But then, there is the corollary; “All the same, when you see the misery it brings, you’d need to be a madman, or a coward, or stone blind, to give in tamely to the plague.” Throughout The Plague, we confront both sides of this moral equation, defined equally by humility and fear. Representing the former is Rieux, who treats patient after patient, past the point of exhaustion, or the magistrate Othon, consumed with helping the quarantine efforts after the death of his young son. As for the latter, there is Cottard, who spends the novel profiteering, only to shatter once the virus recedes. “Was it supposed,” Cottard wonders, “that the plague wouldn’t have changed anything and the life of the town would go on as before, exactly as if nothing had happened?” If he is asking for himself, out of his own corruption, his question, too, belongs to all.

And yet, why not? This is the most important issue, or perhaps the only one. Like A Journal of the Plague Year—or The Decameron or The Cattle Killing—The Plague is narrated in retrospect, after the pestilence has gone. The same will happen this time, although we cannot say how long it will take or how much misery it will cause. And then eventually, as Camus suggests, it will come back again. What this means is that we can’t rely on false illusions, but must engage with the world as it is. What this means is that we can’t involve ourselves in magical thinking, but must take each day on its own terms. That, of course, is only as it should be. I don’t come to literature to be consoled, nor to be distracted; I resist, as well, the notion of books as somehow bettering: guides for living, as it were. What I am seeking, rather, is connection, a to participate in a larger human conversation, from which I can draw if not strength then resolution by encountering, from the inside, other lives. In that sense, The Plague has much to tell us about the dignity of human endurance and perseverance, especially in the face of (mass) mortality. “What’s natural,” Camus writes, “is the microbe. All the rest—health, integrity, purity (if you like)—is a product of the human will.” Contagion, then, is not the exception, but an ongoing state of being, in which we exist at the mercy of each other and the world. That world does not end in Camus’ Oran, just as it did not end in Florence in 1348, or London in 1665 and 1666, or Philadelphia in 1793. Apocalypse is overstated. Or it never happens. Or it is happening every moment—in the biggest and the smallest ways. I say this not to minimize but to offer context, which is the only solace available to us. “[W]hat does that mean—‘plague’?,” Camus asks. “Just life, no more than that.” Contagion or no contagion, in other words, we have no choice but to live.