THE UNIVERSE IN YOUR HOMETOWN

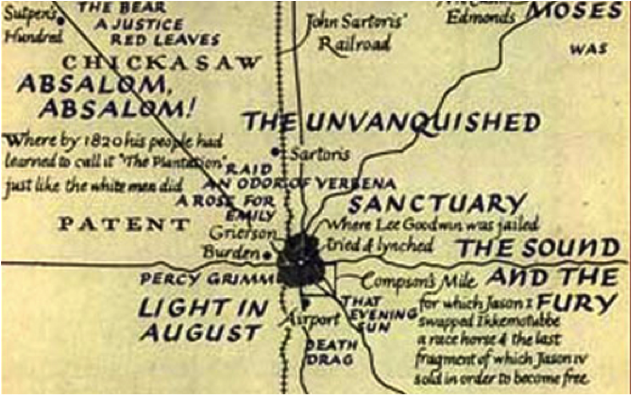

For as long as I’ve been drawn to art, I’ve been drawn to artists who set entire universes in their hometowns, literally or symbolically mythologizing the houses they grew up in, the streets they grew up on, and the people they grew up with. I have a special regard for artists such as Joseph Cornell, Bruno Schulz, William Faulkner, Gabriel García Márquez, Gerald Murnane, and Guy Maddin, who turn the specific wonder and horror of their childhood homes and towns into universal epics, thereby conflating their personal coming-of-age with that of humanity itself. It’s at once a humble and a staggeringly egotistical conceit to use one’s remote hometown as the setting for a novel as universal as The Sound and the Fury or One Hundred Years of Solitude, or a film as aesthetically sophisticated as Guy Maddin’s My Winnipeg, yet this paradox is precisely what animates the singular works of art discussed here.

Collectively, I call these artists the “basement boys,” because the basement is at once the root of the house—thus the innermost point of the individual’s life within the town, and the deepest site of reclusion—and also an access point into the groundwater below, which flows away from the house, through the town, and out into the wider world. By burrowing into the basements of their houses, these artists likewise burrow into the basements of their minds, where it becomes possible to transcend solitude not by moving away from it, but by diving all the way in, down to the realm of myths and symbols where individuation dissolves and a rarefied form of mass communication becomes possible.

There are female analogues to the basement boys, such as Emily Dickinson, who exerted a profound influence on Cornell, but her work, though written while secluded in her house in Amherst, focused on much vaster concerns, rarely if ever using the town as a container for her poetic vision. I have searched for others, but so far haven’t found examples that quite embody the “basement” aesthetic. Perhaps the extreme egotism of electing oneself to preside over an imaginary version of one’s hometown has been inculcated and encouraged as a primarily male characteristic throughout Western history.

This paradox of size, whereby the town contains the universe, is a model for the general paradox of consciousness, whereby we all grapple with how we can exist as specks within the universe and, at the same time, experience the universe as existing within us, as one thought among many. This is the paradox that enables Alan Moore to write a 1200-page metaphysical extravaganza entitled Jerusalem, set entirely within a single section of his hometown of Northampton, England (namesake...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in