I’m in Williamsburg, Virginia, eating lunch with my mom and younger brother when the Olympic dressage competition begins. “I don’t understand how this is a sport,” my brother comments, twisting around to watch a muscled bay with rider spring forward on the HDTV behind us. Neck reined to a curve, the bay completes a neat turn and transitions to bouncing sideways. “The horse does all the work.”

The TVs are muted, so we don’t hear the jaunty backbeat that informs us what a fun time this is. We only see: the unnatural gaits, the stupid display of control. “Is that horse frothing at the mouth?” my mom asks. At first I think the flash is light catching the bit but she’s right: it’s foam. The temperature’s high in Tokyo. The next, unusually glossy horse, we realize, is saturated in sweat. The riders appear just as miserable: their bodies smothered by tailcoats, breeches, and gloves, their movements as tautly restrained as their horses’. No, they’re not the only ones working, but the horses are working hard.

“Doesn’t the horse do all the work?” is a question that circulates throughout T. Kira Madden’s “I Don’t Love Horses,” the stunning first essay in the new anthology Horse Girls: Recovering, Aspiring, and Devoted Riders Redefine the Iconic Bond. As she contemplates the question and her own equestrian history, Madden powers through a harrowing index of human betrayals of horses. The most prominently featured is the story of Sonora Webster, the horse diver whose memoir was the basis for the 1991 film Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken. Though Webster went blind after hitting the water with her eyes open, she eventually dove again. The gutting addendum to Webster’s triumphant story of human overcoming, Madden tells us, is that her horse Lightning was later made to dive into not the usual water tank but the Pacific Ocean. Confused by the currents, Lightning swam out and out until she drowned. “Yes, is the true answer,” Madden concludes. “The horse does all the work.”

Madden is one of many former horse girls contributing their insights and experiences to this anthology. What is a horse girl? Put simply: a girl who rides horses—and who is maybe a little in love with them. Because of the queerness of this ostensible romance, the horse girl is viewed as “unfashionable, out of touch, unsophisticated”—as awkward and ungainly as a long-legged colt. Stuck in the fantasy of horse love, she trades off between rereading Misty of Chincoteague and rewatching Black Velvet—when she’s not in the stables or the corral. Because the love of horses is associated with girlishness and immaturity—in the same way a fangirl’s love of boy bands or a popular TV show might be—the horse girl’s horse-girl-ness becomes seen as increasingly embarrassing as she ages up. That’s the type, anyway—which these writers are attempting to correct. For example, Maggie Shipstead rejects reading equine love as a precursor to or substitute for heteronormative desire: “When a love of horses gets conflated with romantic love or sexual passion,” writes Maggie Shipstead, “the underlying implication is that girls aren’t capable of really knowing what they’re interested in or what they want to do with their bodies.”

Edited by Electric Literature founder Halimah Marcus, Horse Girls collects fourteen absorbing, varied personal essays, each stretching the bounds of the horse girl as a category. For what may initially seem like a niche topic, the anthology offers an impressive range of experiences, together expanding significantly how we think about this type and how it’s shaped by not only gender, but also race, class, region, and ability—while at the same time (and here’s where it gets really interesting) opening up into an inquiry about horse-human relationships overall. What does it mean to glean a sense of freedom from animals we have domesticated to carry us? What does it mean to love so fiercely these magnificent creatures whom we are essentially putting to work?

Though not all of these essays are as devastating or as decisive in their judgments as Madden’s, a streak of uncomfortable ambivalence runs through most, the authors balancing their love of the equine with a clear-eyed view of the unevenness of the horse-human bond. Describing an upbringing spent horse-showing with her mother, C. Morgan Babst laments the normalized cruelties of the sport—bad trainers using weighted shoes and soring to break in new gaits; grooms setting tails by stretching the tendons—as well as the control to which women riders subject their own bodies. Allie Rowbottom reminisces about her beloved horse, Ham, whom she once rode in a racing competition despite the hives lumping over his body. Others are less bothered: “I feel happiest when I can control a horse,” writes Courtney Maum, who plays polo. The essays in Horse Girls simultaneously romanticize and deromanticize the horse-human relationship. One cannot love these animals, these authors suggest, without acknowledging the many harms we have enacted upon them.

Not all horse girls are legible as such. In her kinetic, wide-ranging essay, Carmen Maria Machado describes the type as “lithe teenage girls with impossible French braids” who “smell like heterosexuality, independence, whiteness, femininity.” Not Machado, whose fatness, queerness, and Latinx-ness, she writes, kept her out of the category. Braudie Blais-Billie, who grew up on the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Hollywood reservation, similarly disidentifies with the type, writing, “Sure, I was the weird girl in middle school who kept to herself, read horse-themed YA, and sketched wild stallions on ruled paper. But I wasn’t a horse girl—I couldn’t be.… I couldn’t relate to the privilege or sheltered existence that people around me projected onto the young women who openly loved horses.” She settles on the subcategory “Seminole horse girl,” explaining that “in our family, horseback riding is more than show titles and prestigious stables—horses are how we survive.”

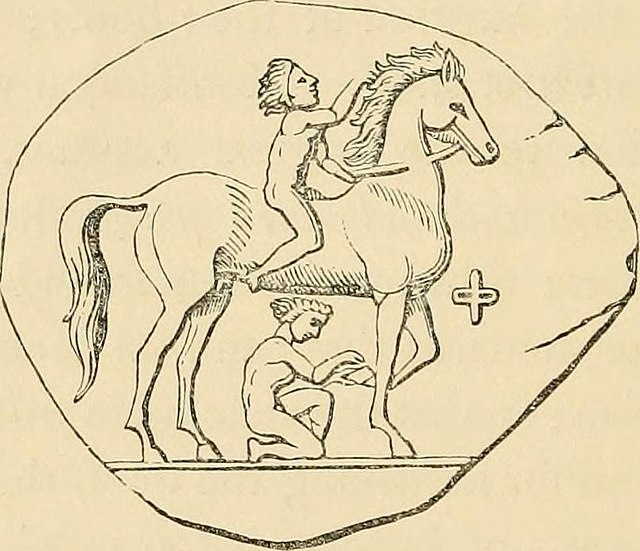

Some of the freshest takes on the type come from those, like Machado and Blais-Billie, who consider themselves furthest from it. Sarah Enelow-Snyder’s essay on her youth as a Black cowgirl in Texas is another highlight, as much for its critical examination of race and class bias in Southern horse culture as for its discussion of Western style contests like barrel and keyhole racing. Alex Marzano-Lesnevich contributes an excitingly transhistorical approach, connecting their trans history of horses with the stories of nineteenth-century gender transgressors. As a whole, the essays are appealingly distinct, even those by writers who perhaps more easily fit the ‘horse girl’ type: Laura Maylene Walter chronicles a trip to Breyerfest, a three-day festival celebrating the iconic Breyer horses; Maum writes about polo horses being set free in Mexico; Maggie Shipstead, about her adventures in riding-related travel assignments.

I was not a horse girl—though like many people assigned female at birth, I developed a fascination with the animal, drawing floating horse heads on my notebooks and taking up riding lessons long enough to learn to canter and fall off, long enough to realize how much time and money it would take to get serious. I may have wanted to be a horse girl, but I felt heavy and uncomfortable in my body in ways that riding generally exacerbated. If my time in the saddle and in the stables was fraught, it was formative enough that I’ve written about it in fiction: in my novel Margaret and the Mystery of the Missing Body my protagonist’s alienation from the horse girl type resonates with Machado’s.

As a kid, I didn’t know loving horses was considered culturally weird, that this was a shameful way to be. But in Horse Girls, shame comes up again and again: the shame of inhabiting (or failing to inhabit) this particular type that is the horse girl; the shame of being recognized as such. Many writers also describe their guilt over having given up—which usually means selling—their horses when riding no longer fit into their lives. In her essay on riding horses in Nathiagali, a resort town in Pakistan, Nur Nasreen Ibrahim explores a different kind of shame, one more related to class and caste privilege. In her introduction, Marcus wonders if this common theme has to do with the “girl” part of “horse girl”—“perhaps shame is a defining characteristic of girlhood,” she writes. “It would follow, then, that girls who experience acute shame are motivated to seek relief for it on horseback.” There, connected to something huge and powerful, a person could feel free.

Back at the restaurant, watching the dressage competition: My brother and I are both wearing shirts emblazoned with wild ponies, souvenirs from a family trip to Chincoteague a few days earlier. The wild ponies live on neighboring Assateague Island, also known as Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. Most years, Chincoteague is the site of the famous Pony Swim, but not this year. In the first break in the tradition since World War II, the event, a huge tourist draw, was cancelled in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At first, I was disappointed to be visiting on this unusual off-year. Like many who grew up reading Marguerite Henry’s Misty of Chincoteague, I’ve longed for decades to witness the spectacle. But I understand now that I misremembered—or reimagined—the swim as an astounding seasonal horse migration, a natural phenomenon that humans simply supported. In fact, what happens is that dozens of foals are rounded up and herded across the channel to be auctioned off to buyers the next day. (See Heather Radke’s essay “Horse Girl” for a fuller description of this event.)

The pony swim is not a natural phenomenon, and neither is the horses’ presence on Assateague. As nonindigenous animals to the island, the annual auction has become an important tool for population control—too many ponies would wreak havoc on Assateague’s delicate salt-marsh ecosystem. The idea for the auction came from the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company. When a 1920 fire destroyed multiple houses on the island, the firefighters realized how ill-equipped they were to do their job and came up with Pony Penning Day as a way to raise funds.

Though this year’s public gathering was canceled, the pony auction went forward, raising a record-breaking $420,000, an average of $5,634 per pony. No, I don’t regret not witnessing these horses’ transition from wildness to domestication. I did see Misty’s taxidermied carcass in the museum, stuffed. When we drove by the fire station, I gasped. It’s a five-garaged palace, massive and gleaming.

Donna Haraway defines “companion species” as a type of kinship defined by “co-constitution, finitude, impurity, historicity, and complexity.” The writers of Horse Girls all describe the specificity of the horse-human bond in this way. There’s no escaping the impurity, historicity, and complexity of the power dynamic in which humans, though lesser in strength and size, always come out on top. Still, the kinship can run deep, and the majority of essays explore it quite movingly.

Writer and horsewoman Jane Smiley understands the bond as collaborative friendship, and unpacks the relationship in her essay “No Regrets”: “As domesticated animals, they are not our servants, they are our collaborators, and they have feelings, or, let’s say, opinions, about collaborating.” Rosebud Ben-Oni’s wonderful tale of her time with Odin, an Icelandic horse, illustrates this dynamic. Odin is a mighty, mischievous tank who has chosen Ben-Oni to be his rider on a five-day trek in Iceland, and the relationship that develops between them is playful, affectionate, deep—and collaborative. Ben-Oni, who lives with a disability, is taking risks with this journey, and chooses to place her trust in Odin. He comes through, and she is rewarded with what feels like friendship—a friendship characterized by mutual respect and even love.

Is this another example of the horse doing all, or the bulk of, the work? Maybe so, but Ben-Oni’s work doesn’t end with this ride. There’s the riding, and then the writing it sparked, which, she tells us, has included numerous stories and poems over many years—and finally this essay, which advocates passionately for Odin and his kind, and which handily justifies the fierce attachments they inspire. It’s a fitting close to a book that is, on the whole, a labor of deeply felt love for this companion species that has supported and surely improved our own.