Little Maurice Gibb, before he was a Bee Gee, fell into a river with the family pomeranian, his siren suit bloating with water. His brother Robin crashed his bicycle into a van, going unconscious for two hours and amnesiatic for six. Ten years later, he survived the Hither Green train accident, in which forty-nine people died. An eighteen month old Barry Gibb yanked on the tablecloth, dousing himself with a full, freshly boiled pot of tea. He fell into a coma, and gangrene grew in his burns. Barry didn’t speak, sing, or even audibly cry for over a year after he returned home from the hospital. A photograph of Barry, decades later: he wears tight jeans, the faded denim pulled taut over his bulging crotch, a thick gold watch and gold necklace, and a red track jacket fully unzipped, lifted open by the wind to reveal pink glades of scars across his woolly chest.

From birth, The Bee Gees were both cursed and blessed to hover on the edge of ruin. As wondrous as their mastery of pop music was their refusal to fade away, their ability to reinvent themselves after dead ends and failures. Their five decade career of music-making was motivated by something different from ambition and more like survival, a fear that to stop is to perish.

How Can You Mend a Broken Heart?, the documentary about the Bee Gees from HBO, is as true to their story as Barry’s veneers are his real teeth. Unlike their generational peers Fleetwood Mac, The Beatles, and Cream, the brothers didn’t generate much gossip. Since childhood their focus was always on each other and their music. Their real spectacle was not that they got sick of each other, but that the general listening public got sick of them over and over again; yet each time, they managed to pull themselves back from the brink and into the charts. Unfortunately How Can You Mend a Broken Heart? focuses on just one of their many nine lives, that of their rebirth from a washed up Brit Pop act into an American disco phenomenon, one which you’ve likely already heard.

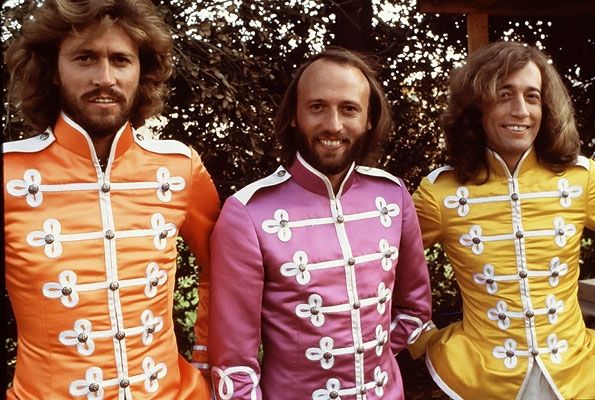

The black sheep of their career, and the most glaring omission from the documentary, is a different film with a story that mirrors their own: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Released just a year after Saturday Night Fever, which the Bee Gees infamously soundtracked, it was a disaster. It has a 17% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Newsweek said it’s “a film with a dangerous resemblance to wallpaper.” Technically, it wasn’t a financial flop. The budget was thirteen million, and it made twenty million at the box office. The film is a 1970s mad lib fever dream: a jukebox musical of Beatles songs, starring Peter Frampton as Billy Shears and The Bee Gees as The Lonely Hearts Club Band, with supporting roles played by, among others, Alice Cooper, Aerosmith, Steve Martin, and George Burns, with the music directed by “the fifth Beatle” himself, George Martin. There are janky singing robots with breasts, a hot air balloon chase, a Hitler Youthesque army, a so-lazy-it’s-genius deus-ex-machina, and the masculine sartorial equivalents of Las Vegas showgirls. It’s an overdose of bubblegum glitz, absolutely gooey in color, and childishly slapstick. It is corny. It is fabulous. It is the height of fashion without being a shade of cool.

The Bee Gees had, from childhood through the 60s, emulated the slightly older and much cooler Beatles. The first time the two groups met was at The Speakeasy bar in London, in 1967. The Beatles had just come from shooting the cover for the Sgt. Pepper’s album and were still wearing their neon silk uniforms. Maurice recalled, “I walked in and John Lennon said, ‘Bee Gees!’… and I said, ‘Hi.’” They made small talk and The Bee Gees slinked away, not wanting to embarrass themselves. Over the next decade, the bands would circle around each other, eventually becoming friends and collaborators. Maurice and Ringo became so close that they moved next to each other, and joked about forming a tunnel between their two houses. The Beatles were the guiding light, the paragon of pop with an undertone of weird in sweet harmony, the first line of the British Invasion that created a path for the Bee Gees to roam, even if they did get lost. Unlike with Fever, The Bee Gees were involved with Sgt. Pepper’s from start to finish. It is their true self-portrait, hidden away in the attic as it distorts and ages through the decades.

Robert Stigwood, film producer as well as their shrewd music manager, always had multiple fires going. While producing Saturday Night Fever and orchestrating The Bee Gees’s turn towards disco, he announced plans for another film, a jukebox musical of Beatles songs. He could pull in his darling boys, add the heartthrob Peter Frampton, and the kitchen sink of 70s celebrities. Considering his success in using the Bee Gees and the handsome and relatively unknown John Travolta to spearhead a film, it is perhaps understandable that Sgt. Pepper’s would seem like a guaranteed hit, but there were warning signs he chose to ignore.

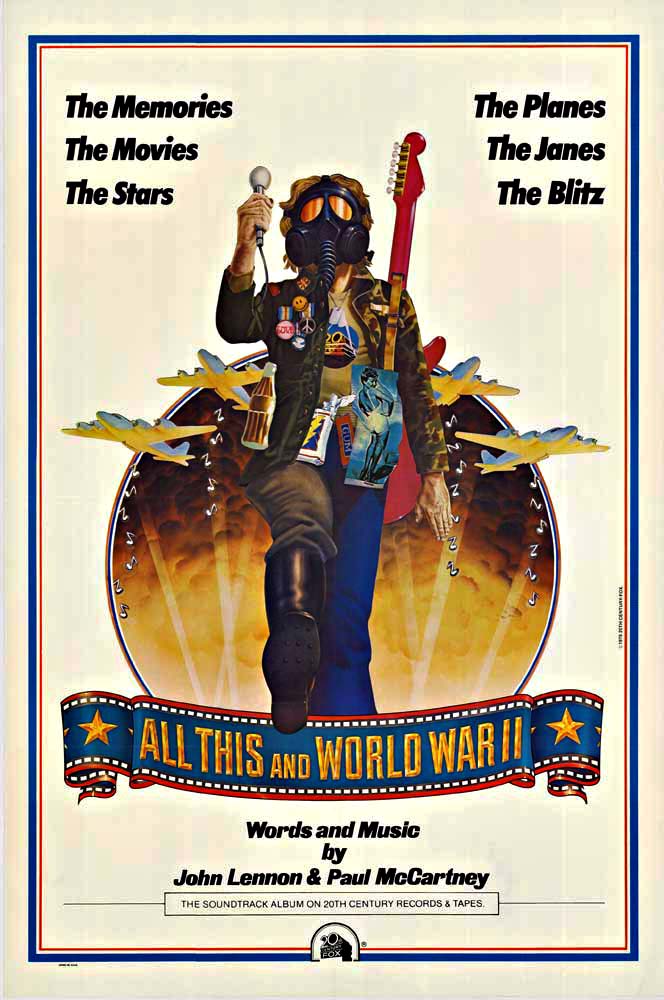

The Bee Gees’s first occasion to cover The Beatles for a film was All This and World War II, a documentary combining old newsreel footage of the war and 20th Century Fox films with the music of The Beatles played by other popular artists, including Bryan Ferry, Tina Turner, Elton John, Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons, Keith Moon, and Rod Stewart. The Bee Gees covered “Golden slumbers / Carry That Weight,” “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window,” and “Sun King,” songs they would later also play for Sgt. Pepper’s. It was directed by Tony Palmer who was famous for his rock documentaries, including a similar project, All My Loving, which combined newsreel footage of the 60s and the music of Cream and Jimi Hendrix, among others. All This… bombed, playing only for two weeks in theaters before being pulled.

The Bee Gees were similarly and surprisingly undeterred when Stigwood approached them with a new Beatles cover project. It had been a dream for years to star in a film. The brothers had been making and starring in their own ambitious home movies since boyhood. Robin had semi-professional equipment and would screen his own films in his home theater. Maurice collected police uniforms and badges, which served as costumes in the little films he made with Barry and Ringo Starr.

Stigwood had produced several highly successful projects before Fever: Jesus Christ Superstar, Tommy, and Bugsy Malone. Had Stigwood won the bidding for the film rights to Hair, the Bee Gees would have made their film debut earlier. When he was with NEMS, Stigwood commissioned a film that the Bee Gees were to star in, Lord Kitchener’s Little Drummer Boys, about some hapless young English men wrapped up in the Boer War—somehow this was to be a comedy. The project languished for years before it was finally dropped. This was their chance.

After Saturday Night Fever, Stigwood had enough cash flow to put serious weight behind his other projects. Michael Schultz was called to direct. He was known at the time for making films about African American life featuring prominent Black authors and comedians, including Greased Lightning, a biopic of the first African American NASCAR driver, Wendell Scott, played by Richard Pryor—not to be confused with Stigwood’s production of Grease, for which Barry Gibb wrote the titular soundtrack song. Sgt. Pepper’s had the largest budget ever entrusted to an African-American film director to that date.

George Martin was persuaded to direct and arrange the music even though, as he said, he knew in his “heart of hearts The Beatles would not have approved.” A few important factors: he admired The Bee Gees immensely, the price was right, and if he wasn’t going to do it, someone else would do it worse. It’s hard to say just how at fault Martin is for the final product. He wasn’t in charge of casting and had to work with what was given to him. Most of the actors are inarguably terrible singers. Frankie Howerd, playing Mean Mr. Mustard, pushes out a painful caricature of “When I’m 64.” George Burns literally shuffles through a version of “Fixing a Hole” that will bore you to tears. Donald Pleasence’s part in “She’s So Heavy” is nauseating at best. The closest we get to the disco sound is Steinberg and Stargard’s cover of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”, which isn’t terrible. Stargard had provided the theme song to Which Way Is Up?, also directed by Schultz, which became a minor disco hit. Unfortunately, Steinberg dominates “Lucy” by wobbling painfully off key. They weren’t all bad. Sandy Farina’s cover of “Strawberry Fields” is lovely; her soft, lilting voice gives sense to the lyrics, although unfortunately the production doesn’t hold a candle to the lush, almost aggressive orchestration that textures and completes the original. Earth Wind and Fire’s cover of “Got To Get You Into My Life” transcended the film into a classic.

Martin enjoyed working with The Beatles’s “junior rivals” as he called them, but there was some problem with recording. He was satisfied with a rougher, more human sounding cut, while the brothers insisted on doing take after take until it was polished perfection. Martin wanted to make double tracks, in which a performer sings over a recording of their own voice to give it a fuller, richer sound, but the brothers’s accuracy made it still sound like a single track. The Bee Gees ultimately got their way. In some instances it’s a plus; a montage of their rise to fame is set to playful a blend of “Polythene Pam,” “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window,” and “Nowhere Man,” which sound fresh with the added satiny funk. Robin’s crystalline, melancholy voice is a perfect match for “Oh! Darling.” Many of their contributions however sound like they took The Beatles songs and dipped them in several layers of glossy wax, and their acting was just as stiff.

Variety called Sgt. Pepper’s a “cotton candy melange of garish fantasy and narcissism,” which is intended as a slight, but this same qualification is a proof that it is a camp masterpiece. It was all it set out to be—a dazzlement of technicolor polyester and nutty comedic romp. The film is truly a marvel, a seemingly never-ending rabbit hole of bizarre choices, all in search of good, tacky fun. Where else would you see Steve Martin playing Maxwell with his silver hammer that magically transforms old people young again, or Peter Frampton wrestling with Steve Tyler on a giant tower of coins? By 1978, tastemakers were well past engaging in good faith anything The Bee Gees touched.

A cultural shift took place in 1979 on Chicago’s Comiskey Park field. Disco Demolition Night was a promotion for a doubleheader game between Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers; admission was discounted to ninety-eight cents for attendees who turned in a disco LP. In-between games, the records were put into a crate and exploded. After that, radio stations started offering “Bee Gees free weekends.” Fever was everywhere, unavoidable, and it got to be just too much; as the brothers had experienced with 60s British folk, their success was the harbinger of the end of a cultural era.

At the end of Sgt. Pepper’s (can something so plastic be spoiled?), a gold weather vane spins into a real life Billy Preston, who belts out a soul version of “Get Back” that is so spectacular, so unlike anything we’ve heard, that he brings the dead back to life. The same year of Disco Demolition Night, The Bee Gees released Spirits Having Flown, their first studio album after Sgt. Pepper’s and Saturday Night Fever. It was the hit they longed for: for the first time ever they had a number one album in the UK. It was also their last. On Spirits they pivoted towards soulful ballads, but it still had residue of a sticky disco label. Their next, Living Eyes, was a far cry in success from the previous decade’s albums, and didn’t release another album for six years, the longest break in two decades. But fear not, gentle reader, for our unbeatable boys: each of their six (not at all disco) albums after went either gold or platinum.

In 1968, Barbara Gibb shared a box at the Saville Theater with Paul McCartney and Jane Asher to see The Bee Gees perform. After the show, according to Barbara, all the girls waiting outside rushed past Paul to swarm her sons, and Paul remarked, “Oh well, it’s their turn now.” What Sgt. Pepper’s tells us about the Bee Gees is that despite how much they wanted to be The Beatles, and were even handed the torch, they couldn’t pretend to be The Beatles forever. They became disco kings in the charts, until they overstayed their welcome there as well, and moved onto the next sound, rising from the ashen glitter, born again and again, getting better all the time.