Early Work

A novel by Andrew Martin

The characters in Andrew Martin’s splendid first book are hungry. Hungry for booze and good food, for transcendence, for success and sex. They are, in other words, normal human beings. But for all their hunger, nothing much happens to them. They hang out and talk and smoke weed and try to write fiction. There’s a love triangle. Despite this minimalist framework, Early Work is utterly enthralling. The book moves at a leisurely, almost Victorian pace, while simultaneously presenting a vivid portrait of our hectic, info-saturated lives. This dynamic is somewhat paradoxical, but it cuts to the heart of what Martin has done: married the shape and texture of a more classical work with modern subject material. The result is an undeniably elegant debut, full of humor and insight and, most crucially, the life of the mind, a thing that many writers attempt to capture but seldom do.

—Daniel Gumbiner, Managing Editor

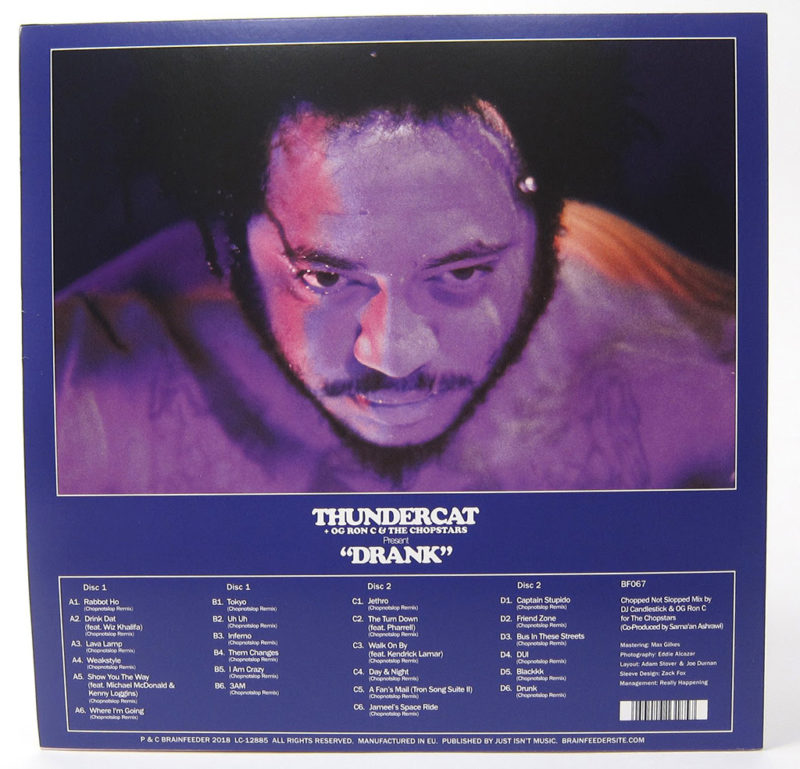

Drank

An album by Thundercat

We talk a lot about slow food and slow eating and slow sex and slow art but rarely, in this day and age, do we talk about slow music. In spite of our collective disregard, there is a history of leisurely modern grooves. In the ’70s, some soul and dance songs were a counterpoint to disco’s frantic clip. Among many others, there were epic vamp-outs by Weldon Irvine (“Morning Sunrise”), and Donna Summer, whose seventeen-minute version of “Love to Love You Baby” probably resulted in the eventual gestation of many many babies who are now forty-two-year-old people. Or how about the sexy, meandering first third of Diana Ross’s “Love Hangover”? Outside of alternative R&B and doom-metal, a lot of contemporary music is uptempo, or at least thematically so. This is especially true of the non-ballads played on the radio. Thundercat’s Drank, released earlier this year, is the chopped-and-screwed remix of his 2017 album, Drunk, and moves at the sedate pace of those ’70s slow-drags.

On Drank, all of the songs are made, with the help of collaborators DJ Candlestick and OG Ron C, using the chopped-and-screwed technique. The method involves a DJ slowing a track’s tempo, or screwing it, to somewhere under 70 beats per minute, and intermittently scratching and skipping it, or chopping it, in order to create more texture within the music. Created by DJ Screw in the early ’90s, the subgenre continues to influence Houston’s rap scene, and hip-hop culture at large. Drank is a play on both the title of the original album and the nickname of the codeine syrup that played a big part in the music’s creation. Chopped-and-screwed tunes make one’s surroundings phantasmagorical, as does the drug that influenced it. To that end, Thundercat’s glorious bass-playing and falsetto are made more ethereal and disorienting by being spliced and rendered in slow motion. “Bus In These Streets” a tongue-in-cheek ditty about staying up-to-date in our hectic era, plays even more ironically given the song’s glacial pace. “Them Changes” resonates differently in its remixed incarnation. When Thundercat demands that “nobody move,” it’s comical. Even if you wanted to, it seems impossible to get anywhere at this sluggish speed. “A Fan’s Mail (Tron Song Suite II),” about what life’s like for a cat, makes you feel like one, especially if you can imagine yourself “sitting in the sun, letting the rays wash over [you].” Drank evokes what it’d be like if David Lynch’s poky-paced, eighteen-hour Twin Peaks: The Return was set at H-Town’s Rap-A-Lot Records circa 1995. Or! If instead of presenting cows grazing for nine minutes in one unhurried long take, the opening scene of Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó showed party people sipping cups of purple drank inside a dirty South club.

Walking around Las Vegas this summer in triple-digit heat while listening to Drank (sober, by the way) felt like wading in water. With Thundercat’s noodling in my earbuds, I often wondered, Is that a mirage? Nah; turns out it was just smog or the smoke sizzling out of a food truck’s pay-window. Drank affects the way you experience the world around you, and this genre of hip hop; the album distorts time in the most delightful way. Moonlight illuminated the rhapsodic beauty of chopped-and-screwed music, but Drankhas made it appropriately intoxicating. “Bittersweet memories, cloud my faded mind / If I was so lucky, I could press rewind” the bassist sings on “I Am Crazy.” I don’t know about Thundercat, but I can press rewind, and I have been. I’ve been rewinding Drank and luxuriating in its sluiced rhythms. It occurs to me that a more fitting title for such a deliciously disorienting morass might be something a bit more saccharine, like molasses, which is sweet and spills long and slow. If you’re lucky, life is like molasses, or, depending on what you like, drank.

—Niela Orr, Interviews Editor

Black Dog in My Path

An album by Yowler

Stubbornly lovely, openly haunted, biblical in scope and vernacular, poetically overblown and also poetically devastating, Maryn Jones’s second album as Yowler cloaks its dark existentialism in lush, lilting ambivalence. You could, as I did, nod along to “WTFK” for a week before noticing she’s been saying “I’m shedding ounces of blood.” Jones, also active in the great rock outfit All Dogs and the baroque jam band Saintseneca, has such an intuitive knack for patient troubadour-folk that it’s surprising, at first, how metal this album’s disposition is. But she sells the apparent contrast both lyrically (“If all we are is sorrow, if all we are is dust, then what?”) and musically, starting with grainy lo-fi warmth and layering in a slow undertow of scorched-earth distortion. “Petals” is an achingly pretty lover’s lament; “Holy Fire” is a prayer circle held above an active volcano; “Where Is My Light” is the Cranberries’ “Zombie” recalibrated for a moment when the tanks and the bombs and the guns are both literal and psychological. Not that Black Dog in My Path is a zeitgeist album: it’s hopeful and despairing and wise in the shifting proportions of any great pop album, which is to say it’s timeless. But it also happens to pinpoint beautifully the schizophrenia and indecision of the present, the sweet airy highs and the blackened lows, the unhurried majesty of being alive and of knowing one day you and everything around you won’t be.

Stubbornly lovely, openly haunted, biblical in scope and vernacular, poetically overblown and also poetically devastating, Maryn Jones’s second album as Yowler cloaks its dark existentialism in lush, lilting ambivalence. You could, as I did, nod along to “WTFK” for a week before noticing she’s been saying “I’m shedding ounces of blood.” Jones, also active in the great rock outfit All Dogs and the baroque jam band Saintseneca, has such an intuitive knack for patient troubadour-folk that it’s surprising, at first, how metal this album’s disposition is. But she sells the apparent contrast both lyrically (“If all we are is sorrow, if all we are is dust, then what?”) and musically, starting with grainy lo-fi warmth and layering in a slow undertow of scorched-earth distortion. “Petals” is an achingly pretty lover’s lament; “Holy Fire” is a prayer circle held above an active volcano; “Where Is My Light” is the Cranberries’ “Zombie” recalibrated for a moment when the tanks and the bombs and the guns are both literal and psychological. Not that Black Dog in My Path is a zeitgeist album: it’s hopeful and despairing and wise in the shifting proportions of any great pop album, which is to say it’s timeless. But it also happens to pinpoint beautifully the schizophrenia and indecision of the present, the sweet airy highs and the blackened lows, the unhurried majesty of being alive and of knowing one day you and everything around you won’t be.

—Daniel Levin Becker, Reviews Editor

A nonfiction book by Jesse Ball

“How will you be expected to interact with these readings?” Jesse Ball asks halfway through Notes on My Dunce Cap (Pioneer Works Press, 2016), his slim, artful, and stimulating book on pedagogy. The accomplished forty-year-old writer’s response is an assignment: to deliver a “short letter, no more than a page, discussing something pertaining to the book in question,” written to him “in a clever way.” In a sense, this note could be considered one such letter.

“How will you be expected to interact with these readings?” Jesse Ball asks halfway through Notes on My Dunce Cap (Pioneer Works Press, 2016), his slim, artful, and stimulating book on pedagogy. The accomplished forty-year-old writer’s response is an assignment: to deliver a “short letter, no more than a page, discussing something pertaining to the book in question,” written to him “in a clever way.” In a sense, this note could be considered one such letter.

The book opens with a disclaimer: “It is crucial that what happens when we teach be of the same value as time spent alone.” For Ball, teaching (and thinking about teaching) should be joyous, virtuous, and pleasurable as “sitting somewhere in the grass.” And, for the most part, in Ball’s nimble hands, it is. Other tips are similarly radical: “The teacher should at all times resist authority,” one’s own authority included, and later: “A good teacher says as little as possible.” The idea of value shows up again: “Try to make the materials that you give the students be as valuable as possible,” he writes. Your handouts, even your emails, should be beautiful, modular, encouraging, and “redolent of your own joyful life.” It’s an exacting standard, to be sure, and perhaps not entirely realistic. But a lazy teacher is never an inspiring one, and Ball is ceaselessly diligent as an instructor and exemplar.

The second half of the book consists of syllabi to courses the self-identified fabulist and absurdist has taught at the School of Art Institute of Chicago on topics like lying, lucid-dreaming, and Kafka. Adventurous, thorough, painstakingly written—Ball admirably refuses to traffic in boilerplate—these syllabi are also a major blind spot. “The teacher must see to it that those who would ordinarily be excluded by the group are included,” he exhorts, but the syllabi exhibit a near-exclusive reliance on reading white male authors. Still, as Ball writes, “the principal thing that you should attempt to give students is an opportunistic bent, that there is always something to learn in every situation, and that the student must devise a way to learn it. Those who do this cannot be stopped from creating wondrous frameworks and filling them effortlessly with data.” Notes on My Dunce Cap is one such framework, filled with useful data, and we the readers could do much worse than to engage it, with interest and intent, ideally someplace in the grass.

—James Yeh, Features Editor