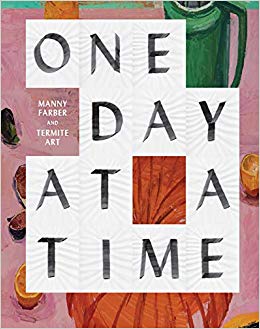

One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art

Museum of Contemporary Art, Companion Book by Helen Molesworth

Walking into “One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art”—the final show at Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art with former chief curator Helen Molesworth at the helm, unfortunately, but what a way to go out—I found that my first task was to get my bearings. Painter Manny Farber’s canvasses are crowded with stuff: notes with obscure directives that take the character of mantras (“Order everything in place,” reads one), suggestively placed eggplants, broken chocolate bars scattered across a desk, staplers perched next to asparagus stalks, miniature women shimmying out of or into bikinis, tiny cowboys strutting cutely, out of context. Standing before ones of these paintings, it can be difficult to figure out where your eye should land, where Farber’s compositions want you to enter.

Take a painting like “Rohmer’s Knee:” its circular canvas is populated by bikini-clad women wandering a landscape of watermelon slices, rulers precariously balanced upon cheese wedges, and magazines thrown wide open to the viewer. It is composed as a closed loop of incessant action; there’s no obvious resting point, no static moment. A model railroad track—circular, of course— sits like a halo at its center; picking up on its cue, my eye wanders in circles around the canvas.

Before he traded his New York apartment for a position teaching art at UC San Diego in 1977, Manny Farber worked as a film critic, and there is indeed something filmic about his paintings. They’re imbued with a chaotic sense of movement that goads the viewer into unceasing motion. It’s the only way to enter these paintings, which free-associate Farber’s obsessions (included but not limited to Westerns, candy, the films of Fassbinder, and women) into miniature dramas. In his most famous essay, “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” (which Molesworth includes in the exhibit’s companion volume), Farber decried the lethargy of “masterpiece art” that subdued an artist’s personal interests to the requirements of monumental compositions obsessed with grand statements. Such art found an artist’s vision “squandered in pursuit of the continuity, harmony, involved in constructing a masterpiece.” In the masterpiece’s place he lionized “termite art,” which was concerned only with giving voice to quotidian “in a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor that isn’t anywhere or for anything.”

Farber’s paintings feel like a visual companion to his critical notions. Every corner of a canvass has the potential to house a minor drama: the interplay between black and yellow that animates “Patricia’s a Legend,” for instance, or the tension springing from the way a ruler balances upon the model train set in “Rohmer’s Knee.” You’ve got to let your eye wander, though, and you’ve got to pay close attention. As much as Farber’s work seems to encourage cinematic motion, it also feels like a call to allow the eye to rest upon the stray detail, without any need to absorb it into a larger structure. Walking through the exhibit, I felt myself enveloped in something soft, sumptuous, a feeling like nuzzling up against velvet. It felt like the opposite of the Internet’s totalizing grind.

—Ismail Muhammad, Reviews Editor

You’re Wrong About…

A Podcast by Sarah Marshall and Michael Hobbes

Anna Nicole Smith. Jeffery Dahmer. Lorena Bobbitt. These are names I last saw in out-of-date copies ofPeople magazine while waiting for a dentist’s appointment a very long time ago. You’re Wrong About… is a podcast that seizes on such figures from the past and sends them hurtling into the present. And it’s making me understand why I might want to remember them. Hosts Sara Marshall, who has written forThe Believer and many other publications, and Michael Hobbes, a reporter for the Huffington Post, are our savvy and rigorous guides through one-time media frenzies that have now reached the status of folklore. The titles for each episode read like shorthand for wider cultural phenomena: “Stranger Danger,” “The 2000 Election,” “Columbine,” “Amy Fisher.” The weekly premise is to re-investigate one such person or event, which seemed to hold everyone’s attention for a time, usually at some point ca. 1980-2005, not uncoincidentally during the rise of the 24-hour news cycle.

Sarah and Michael find out where the dominant narrative went wrong or just went weird. But despite the title, the investigative exercise isn’t about finger-wagging from a safe critical distance. Yes, villains appear—namely lazy reporting and capitalism. But some of the most captivating episodes have the hosts caught up deeply caring about people they probably stopped thinking about a long time ago, like the NASA scientists involved in the Challenger disaster, or Crystal Gail Mangum, who was at the center of the Duke lacrosse rape case. Sarah says in one episode: “We are in a real sense Ghostbusters, because we’re going around and finding these pieces of dangerous lore and superstition, and [we’re] neutralizing them.”

Like a good mystery, there are usually surprise twists, and the show is often laced with dark humor and hard truths. You’re Wrong About… is a study of the stories we absorbed into the fabric of our collective memory, but never had the chance to fully understand. I recommend starting with “Stranger Danger” or “Lorena Bobbitt.” The podcast is less than a year old, so you can catch up fast.

—Michael Ursell, Associate Publisher

Through a Life

A Graphic Novel by Tom Haugomat

This nearly wordless graphic novel out from Nobrow this month is like one extended gut punch over the course of 200 pages. Comprised of single-image vignettes, Tom Haugomat builds the biography of a boy who grows up to be an astronaut, and all the minutia that takes place below the sky he longs for. Constructed of gorgeous, flat screen-print style drawings, a whole life comes to pass without a line of narration or dialogue—love and its failings, depression, and a tragedy in space that keeps the protagonist tethered forever to earth.

This nearly wordless graphic novel out from Nobrow this month is like one extended gut punch over the course of 200 pages. Comprised of single-image vignettes, Tom Haugomat builds the biography of a boy who grows up to be an astronaut, and all the minutia that takes place below the sky he longs for. Constructed of gorgeous, flat screen-print style drawings, a whole life comes to pass without a line of narration or dialogue—love and its failings, depression, and a tragedy in space that keeps the protagonist tethered forever to earth.

—Kristen Radtke, Art Director

A Wild Yeast

Sourdough Starter

When my family became tenants of our friends’ house this winter, they asked if we’d be willing to tend to their sourdough starter. (Sourdough starter, for the uninitiated, is a ferment of flour and water that becomes a medium for wild yeasts, and is used to leaven bread.) “It’s easy,” they said. “Just feed it. Use it once in a while.” We were  apprehensive. But since we’d already declined to dog-sit their mini goldendoodle, minding some yeast seemed like the least we could do. However, as Sam Sifton puts it, sourdough starter can become “a pet you maybe didn’t know you wanted until someone hands it to you.”

apprehensive. But since we’d already declined to dog-sit their mini goldendoodle, minding some yeast seemed like the least we could do. However, as Sam Sifton puts it, sourdough starter can become “a pet you maybe didn’t know you wanted until someone hands it to you.”

Sourdough starter needs warmth, food, and attention—just like any living thing. If you’re not baking with it, it hibernates in the fridge. Once a week, though, you have to pour out a cup of it, discard the rest, and feed it with two cups of flour and one cup of water. If it starts to separate and liquefy, consider it a cry for help, and you need to give it more warmth and feedings until it begins to bubble and emit a yeasty smell once again. After a few weeks, you may find your starter has a name, and a wool blanket, and a coveted spot by the heater. You may even start to feel the stirrings of love.

—Caitlin Van Dusen, Copy Editor