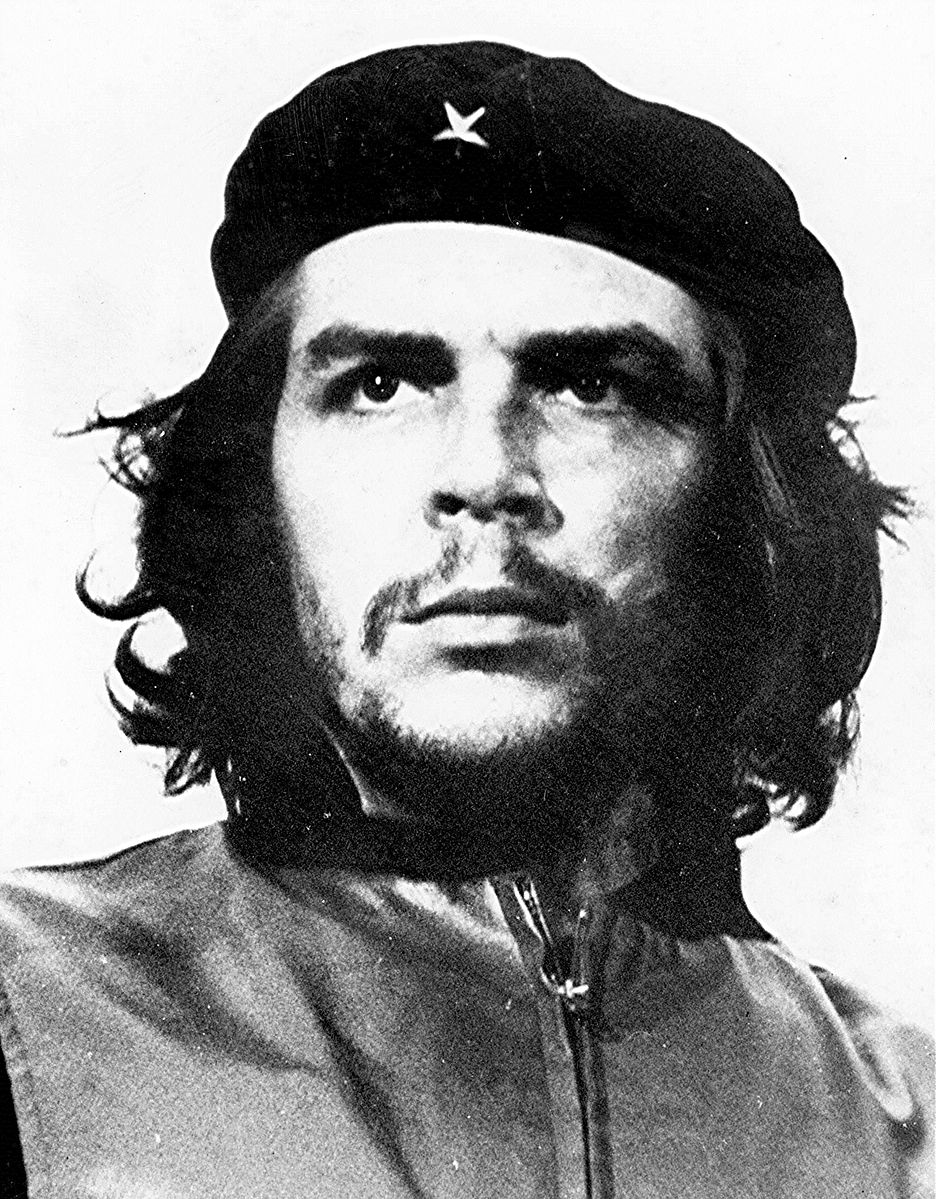

It was a late September afternoon in 2017, and a 25-year old officer in the U.S. Army had just tweeted an image of himself in a Che Guevara t-shirt. The photo showed him at his West Point graduation in 2016, his neat dress grays parted to reveal a silkscreen of “The Heroic Guerilla,” Alberto Korda’s iconic 1960 photograph of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the fire-eyed Argentine militant and hero of the Cuban Revolution. Che was pictured from the chin up, his dark hair flowing behind him, his eyes blazing beneath the man’s vest and his brass-plated service medallions.

Once a proud enlistee in an elite Ranger unit, Second Lieutenant Spenser Rapone had lost his faith in the Army, outraged by the abuse of civilians he’d seen on a tour in Afghanistan. Now stationed at Fort Drum, New York, with the 10th Mountain Division, he hoped his Che Guevara tweet would accomplish three objectives: expose the US Military as a “force of imperialist aggression”; express support for national anthem protests at sporting events; and prod his commanding officers to grant him an early discharge. These broad, somewhat disparate, aims found a common expression in Che, who’s been a potent, and pliable, emblem of dissent since his death in 1967.

The response to the tweet was overwhelming. Military boosters rushed online to voice their disapproval, Che admirers far and wide tweeted their support, and the West Point selfie morphed into a viral Rorschach Test. We viewed “The Commie Cadet,” as journalists dubbed Rapone, through the same blurry lens that millions view Korda’s photo: with little knowledge of the man in the picture; as a blank canvas for our hopes, fears and beliefs.

When Rapone’s post entered my timeline one chilly autumn night, I shivered with recognition. I had spent much of my youth in a “Heroic Guerilla” t-shirt and I was starting to gather the stories of people like me and him, the restless Millennial youth who have dragged the “Korda Che” into the digital age. They represent a staggering range of cultures and subcultures—Salvadoran doctors and Yazidi refugees; Siberian paintball players and Bosnian “biker chicks”; Marxist students in India and neo-fascists in Italy, to name just a few I’ve interviewed over the past three years—and their posts on platforms like TikTok, Twitter, and Instagram have been viewed millions of times.

But amid all the furious tapping of picture and video apps—all the selfies, the hashtags, the parody memes—no post has received a stronger response than Spenser Rapone in his Che shirt. An utterly singular image, unique in its stunning blend of imperial symbolism and revolutionist chic, it thrusts us into a virtual world where photos are social currency; where politics hinge on aesthetics as much as on inner conviction; where an image can mean anything to anyone.

And like the global youth who wed their lives to Che’s picture, an image widely considered the most reproduced photo in history, “The Heroic Guerilla” moves through this world in a state of revision and flux. It has long outlived its subject. It has left its creator behind. And now, as it enters its seventh decade, it is having its next great awakening, a dizzying digital renaissance on the outer limits of meaning.

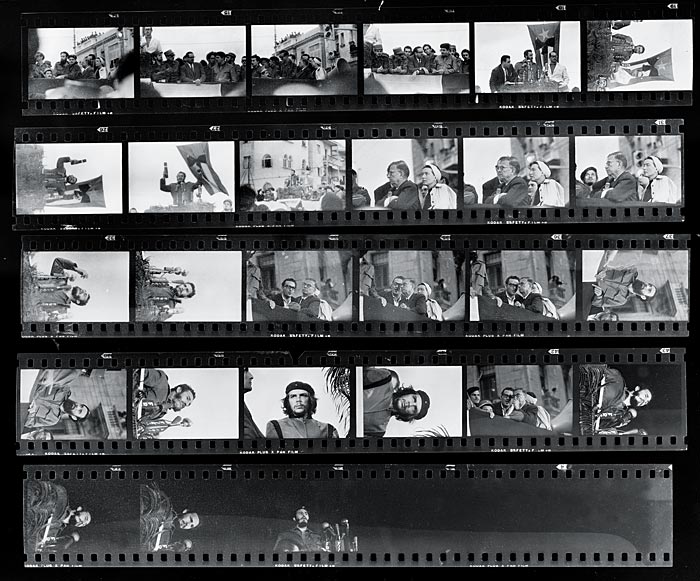

On the cool, windswept afternoon of March 5th, 1960, the Cuban photographer Alberto Diaz Gutierrez—known to friends and colleagues as “Korda”—was sent to cover a state funeral in Havana. A French freighter had just exploded in the city’s harbor, leaving seventy-six dead, and the editors of Revolución, Cuba’s most prominent newspaper, were requesting photos of the ceremony.

When mourners gathered outside the gates of the historic Colón Cemetery, Korda’s eye was drawn, inexorably, to the most photogenic official in the country’s new regime. Thirty-one-year old Che Guevara was framed against a slate gray sky, his swarthy features crowned by his signature beret. As Fidel Castro blustered his way through a combative eulogy, and feverish cries of Patria o muerte rang across the crowd, the face in Korda’s viewfinder seemed, as he would later recall, to gleam with “steely defiance.” Korda pressed the shutter.

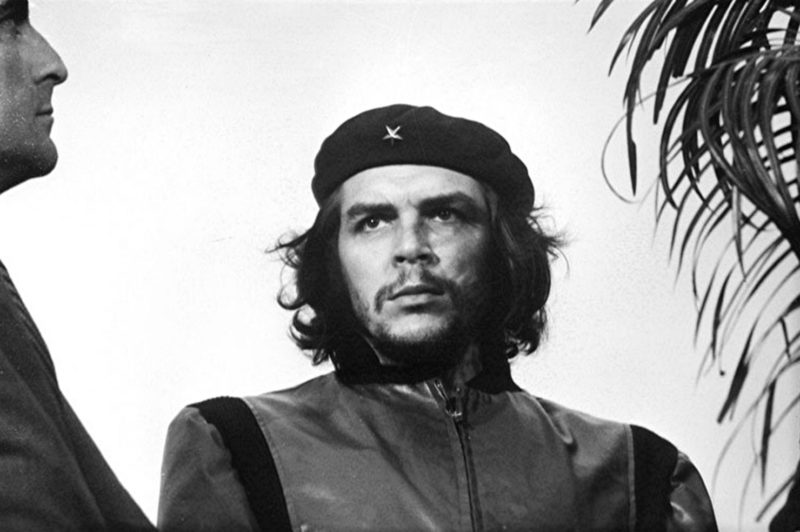

The image that bloomed in his dark room that night was a wider version of what became known as the Guerrillero Heroico, or “Heroic Guerrilla”: Che’s torso anchored the centre frame; an Argentine journalist filled the left foreground. A successful fashion photographer before the Revolution, renowned for his glossy spreads in Vogue and his reverence for female beauty, Korda had learned to adapt his skills to the rigors of daily journalism. Faced with the space constraints of the Revolución news section, he made the pragmatic, and fateful, decision to crop this original picture, separating Che from his surroundings. The result was an image untethered to time or place, an image whose subject could be whoever we wanted—or needed—him to be.

But there was nothing predestined about its journey around the world; nothing fated or certain. The image’s youthful following, and the historical milestones that sustain and renew it, must be traced back in time to a massive contingency.

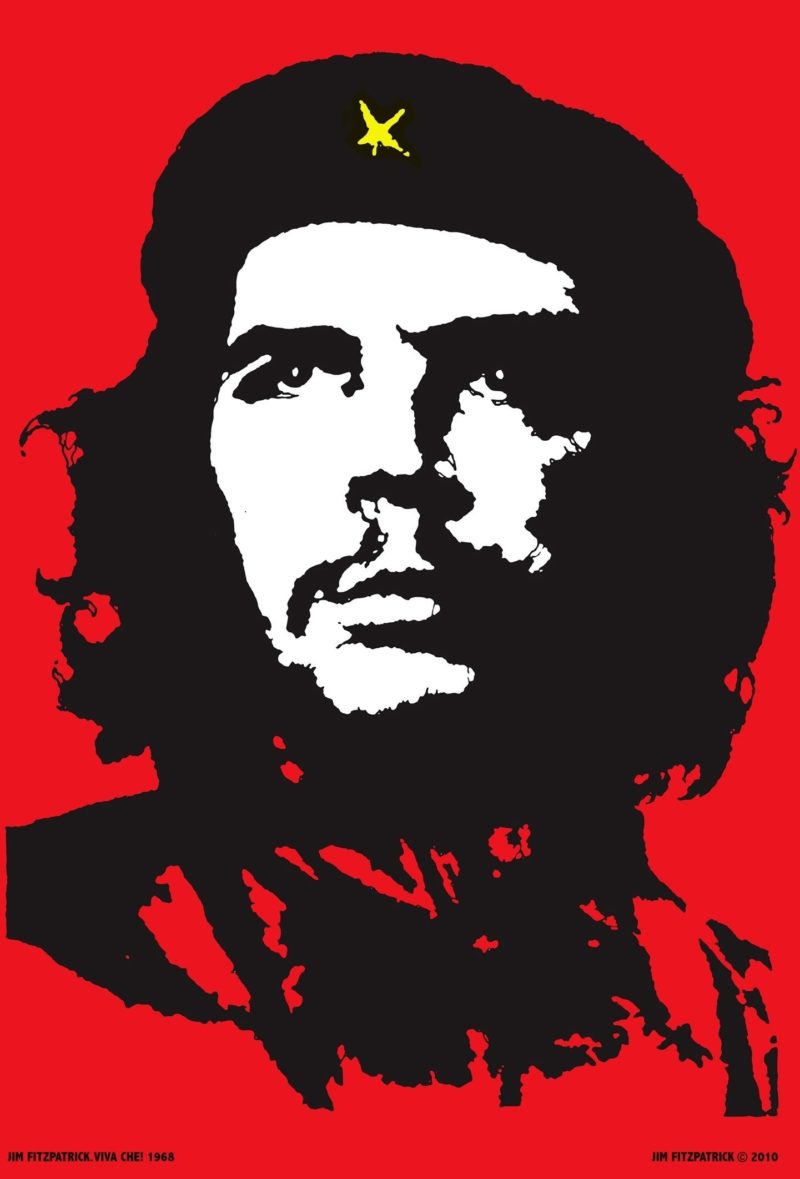

Che’s killing by the Bolivian Army in October, 1967, was a Cold War watershed—and the moment that thrust the Korda Che in the global spotlight. As news spread of the leftist heartthrob’s final, failed revolution, Italian publisher Giacomo Feltrinelli seized the moment, selling millions of copies of a print he’d been gifted by Korda. (Korda received no attribution or compensation.) The following year, Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick’s stencil, a two-tone reproduction modeled on Catholic icons, scattered across student barricades from Mexico City to Prague.

“Long before the internet, I set out to proliferate [Korda’s] image,” Fitzpatrick, now seventy-six, told me from his Dublin studio. “I wanted it to breed like rabbits.”

Unconstrained by copyright law, which Castro deemed anti-socialist, this goal was quickly realized, and the fall of global communism did nothing to impede it. “The Heroic Guerilla” remained a fixture on countless t-shirts and posters, while also becoming a popular logo on new consumer products. There were Che snowboards from Switzerland, air fresheners from Peru, and a notorious ad campaign for a “spicy” Smirnoff vodka, an application so grotesque it prompted the aging Alberto Korda to file his first copyright claim.

By the late 1990s, many historians and curators designated the Korda Che the most reproduced photo in history, a distinction it still maintains. Quantifying this label has always been “a bit hazy,” said the curator Brian Wallis, a former director of the New York-based International Center of Photography, but “it was hard to think of another photo that had such a wide array of [uses].” As the image swept through the open markets of a unipolar world, a question whispered since the late sixties grew to a deafening roar: why embrace a Marxist icon at the nadir of his cause?

The answer lay, at least in part, in Che’s postmortem mystique, which recast his political failures as heroic defeats. But it also lay in places too mysterious, too shrouded in contradiction, to sustain a cohesive theory; the very places where, as Wallis noted, Che’s biographers, Korda’s curators and score-settling pundits of every persuasion have never bothered to look: the hearts, minds and internet profiles of people like me and Rapone.

Like many of my millennial peers, I can’t recall the first time that I saw “The Heroic Guerrilla”; only that by the fall of 1997, when I entered the 8th grade at my Toronto middle school, the image had filtered throughout my world, as bold and omnipresent as the Nikes on my feet.

That July, Che’s remains had been found in southern Bolivia, ending decades of speculation on the site of his burial. The international fanfare that greeted this discovery and its eerie proximity to the 30th anniversary of his death combined to give the Korda Che its greatest cultural currency since the late 1960s.

As it splashed across new Che-themed books, and anchored photo exhibits, and loomed above the crowds at Che memorials that fall, young people around the world were meeting the Korda Che—and loving what they saw. The image became a talisman, a symbol of our porous world and its seething discontents. We wore it to school on the crimson shirts of Rage Against the Machine. We hoisted it high at rallies in London, Brazil and Seattle, pledging support for workers movements challenging corporations. At home, at night, in the privacy of dial-up-connected bedrooms, we brought it into the chat rooms where we nurtured these passions online.

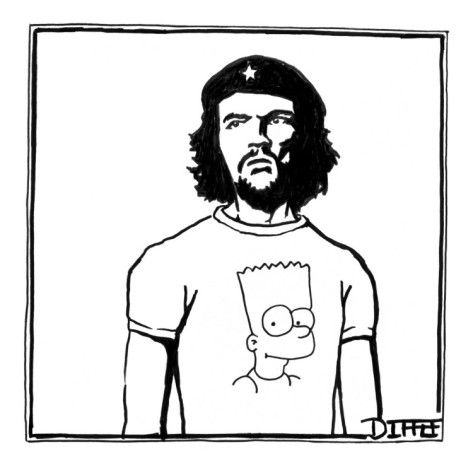

As our visibility grew, cultural critics like Paul Berman, writing in Slate, and the Peruvian pundit Alvaro Vargas Llosa, writing in The New Republic, began to call us the new “Cult of Che,” reviving a term that Time had used for his Western fans in the Sixties. Alarmed by our tendency to tie the image to a romantic creation myth, in which the young Ernesto Guevara rejects his bourgeois privilege and topples a Cuban tyrant, they asked us to widen the frame. What of the La Cabaña prison, where Che oversaw executions at the end of the Cuba campaign? What of his failed insurrections in the Congo, Argentina and Bolivia, aptly described by Jon Lee Anderson, in his masterfully reported Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, as “a miasma of blood and wasted lives”? There was a growing sentiment, expressed everywhere from conservative blogs to parody t-shirts to sitcoms and New Yorker cartoons, that we were looking at half the picture.

Of all the lessons I had to absorb when I moved to the US for college—a washroom was a “bathroom”; a Colt 45 was a drink—none were more of a wake-up call than the perils of wearing a Che shirt. Even though my campus was widely viewed as a liberal hotbed, I couldn’t rely on the Korda Che to bring me the love that it used to—the fistbumps from strangers at concerts; the nods of fraternal approval while protesting Bush’s wars.

This was made clear early on by a hallmate whom I’ll call “Carmen,” the scion of a Cuban family that fled the Castro regime. Carmen saw pain in Che’s image that I was too smitten to notice: the summary trials of loved ones, the confiscation of land, the violence he had overseen from the ramparts of La Cabaña. And though I tried my best to laugh and shrug her off, this grim sartorial critic planted a seed of doubt. She forced me to project an island’s bitter history onto the hyper-modern global icon I admired.

By the winter of 2005, when guitar legend Carlos Santana performed at the Oscars in a Che shirt, the picture in my head had shifted. The soaring coming-of-age tale I’d built around the image had acquired a gut-wrenching postscript—a montage of shackled dissidents, sun-baked prisons and blood-streaked Bolivian arroyos. That summer, as the first Che fan pages started to pop up on Facebook, I took a trip to Toronto and left the shirt in a drawer, next to the baggy jeans I’d retired after high school. For a brief and bittersweet moment, “The Heroic Guerrilla” held a place among the relics of my youth.

It didn’t stay there long. When I moved to DC after school to start a career as a journalist, I couldn’t seem to escape it. It was appearing at anti-austerity rallies all over southern Europe, at the Occupy protests on Wall Street, at the surging demonstrations known as the Arab Spring. And when I stared through the glowing portal of my first-ever smartphone, I saw youthful scenes that far eclipsed Fitzpatrick’s dreams of multiplying stencils: the Marxist youth on Instagram in India and Turkey, sharing Korda’s image over fiber-optic cables; the goofy online videos like “50 Grades of Che,” in which Che’s portrait burst to life on school yards and report cards.

Despite the belated efforts of Alberto Korda’s estate, which had started asserting more copyright claims when he died in 2001, the Korda Che was scattering at algorithmic speed, propelled by young adherents of every creed and culture. By the fall of 2017, when Spenser Rapone went viral, there were Che-themed hashtags with posts in the hundreds of thousands. Then, as now, the maelstrom of images summoned a difficult question: what connects the members of such a disparate tribe?

For some I’ve met, Che’s iron gaze offers a visual anchor, a source of inner ballast during times of personal flux. When Zhao Jin moved to New York from China in 2013, the 29-year old software engineer sought a private totem, a symbol that would reconcile her family’s Communist values with the freedoms she enjoys today in the Western middle class. A Korda Che tattoo now glowers from her shoulder, and in the frequent selfies she posts on Instagram—a constant daily reminder to not “lose sight of [her] dreams.”

Others describe the image in the language of survival. When Kherallah Suliman Neamah first saw the Korda Che, emblazoned across a baseball cap at his local bazaar, he was only three years removed from surviving an ISIS massacre. Now living in harsh conditions at a refugee camp in Zakho, a city on the Turkish border in Iraqi Kurdistan, the 16-year old Yazidi boy has found a measure of comfort, and a welcome distraction, in crafting black-and-white paintings of the famous image. “I really liked the picture,” he told me in an email, sent from the local art workshop he attends through an Irish charity. “Then I went to read [Che’s story] and I like it more.”

For Teodora, a 35-year old Serbian woman in Bosnia, the Korda Che will always be linked to another recent war: the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia at the end of the 1990s. While American Tomahawk missiles were raining down on the Balkans, she was attending a high school in which she was the only Serb, and a frequent target for bullies when sectarian tensions flared. After weary days of fending off insults, punches and rocks, she’d turn to the Korda Che in a family encyclopedia, asking the man in the photo to grant her some of his strength. Now a successful dentist and self-proclaimed “biker chick”, she’s kept the image close to her for over twenty years—first on an early flip phone, then on her Facebook profile, and today at the biker festivals where she buys Che Guevara t-shirts and posts them on Instagram. “I wear his shirt because he was such a big part of my life,” she said. “Like a long lost friend.”

As touching as it is to observe such an intimate bond—the link between subject and viewer that Roland Barthes used to call a photo’s “umbilical cord”—it can also be disorienting. Hear enough of these stories from different parts of the world and Korda’s once-monolithic portrait starts to break apart, a photo made up of photos, each with its own bitmap. The more its competing versions proliferate online, the more the conflicts between and within them grow increasingly stark.

Consider the examples of Georges Fadel, a 23-year old security guard in the suburbs of Beirut, and Ezio Palermo, an unemployed 34-year old in Catania, Sicily. On June 14th of last year, the day that would have marked Che’s 91st birthday, these two strangers separately posted the photo on Instagram. But where Fadel described it to me as a symbol of peace and tolerance—“I fucking hate RACISM”, his profile proudly declared—Palermo applied the jaundiced gaze of an ardent neofascist. Like many supporters of “CasaPound”, a far-right movement in Italy notorious for its harassment of migrants and journalists, he treats “The Heroic Guerilla” as an emblem of anti-state rage, hoisting it at rallies, and posting it on online, next to graphics of Mussolini.

Since I started message threads with these two men over the summer, I’ve felt as though I’ve entered an interpretive abyss. I’ve come to think of the Korda Che as an image without a story, imbued with so many meanings that it’s starting to lose its meaning. I’ve wondered if the dangers of the social media age, embodied in so many ways by the anger of men like Palermo, require new symbols of resistance.

Or as the curator Trisha Ziff, one of the photo’s leading historians, put it to me when I called her at her Mexico City studio: do we really need more “images of hot men with cigars pontificating?”

These are points that Spenser Rapone has been pondering since 2018, the year he left the Army with an “other than honorable” discharge. When we connected last year, two years after his tweet, he said he’d been reflecting on his history with the image.

As a working class kid growing up in the Pennsylvania Rust Belt, the Korda Che had struck him as a colorful enigma. It wasn’t until he’d fought in a war, and begun his studies at West Point, that he acquired the “political consciousness” to put the photo in context.

In the summer of 2015, while reading The Motorcycle Diaries, Che’s famous memoir of political self-discovery, the image started to merge in his mind with memories from Afghanistan—with visions of innocent Pashtuns shackled and shrouded in hoods; with the dreams of “fight[ing] for freedom” that were dashed by the mission he’d served. Two years later, he channeled his outrage into his viral tweet.

The scope and fury of the response came as a bit of a shock, but even though it exposed him to the dark side of online politics—to insults and death threats; to the censure of a U.S. Senator—Rapone told me he saw it as proof that the Korda Che still has meaning. If a simple tap of an iPhone could anger so many people, and win him the solidarity of strangers around the world, then didn’t that show “the spirit of Che [remained] alive and well”? Now a graduate student at the New School in New York, and a committed activist in the Democratic Socialists of America, Rapone was more convinced than ever the image would stay a “beacon,” inspiring the many young Americans who, recent polls suggest, have grown fed up with capitalism.

Not every admirer retains such firm conviction, and I’ve encountered other stories closer to my own: the 26-year old Irishman who’d spent his youth in a Che shirt and told me he now considered the Korda image “a little passé, a little adolescent”; the Bangladeshi college student who called it a “picture of courage” but felt that Che “should have had more proper technique on his revolution.”

Yet for every aging cynic who drifts away from the frame, there is a young admirer who is ready to take their place, a breaker in what Trisha Ziff called the “digital tsunami.” Georges Fadel in Lebanon said he’d never heard of Che until the day last spring when a YouTube algorithm introduced them. Two weeks, and countless TED-X videos, later, he was posting his birthday tribute, using the Korda image to honor “the revolutionary king that challenged America, that changed the course of history.”

Examples like this are what give hope to the photo’s oldest custodian. “90% of the people using the image today have no idea who Che is,” Jim Fitzpatrick said, “but even if only 1% do, then I’m a happy boy.” He continues to keep a high-res version free for download on his website, and to take immense satisfaction from the global youth who embrace it.

Like Zhao Jin in New York, rubbing her tattoo for luck. Like Kherallah in Iraq, who sends Fitzpatrick sketches through an aid worker they know. Like the young man formerly known by the nickname “The Commie Cadet,” whose journey from Army Ranger to spirited “war resister” inspires Fitzpatrick every time he reads about it online. “You tell Spenser I say hello,” he said the last time we spoke.

These are the changing faces of one of the world’s most visible, yet increasingly unclassifiable, subcultures—a cross-cultural, post-ideological tribe for whom his graphic, and the photograph that inspired it, are the sole remaining touchstones.

And this, in Fitzpatrick’s fading eyes, is the natural order of things. When Alberto Korda cropped his photo on that cloudy night in Havana, it no longer belonged to a moment or movement in history. When Fitzpatrick traced it against the pane of a frost-tipped Dublin window, he ensured the resulting stencil would soon “belong to the world.”

“When you open Pandora’s Box there’s no point in trying to shove it all back in,” he said. There are certain images so powerful they “demand to be reused and reborn and reinvented.”