Early April, 2020. Kids are upstairs rewatching Steven Universe; they’ve eaten dinner. One of them’s in their pajamas. Jessie is reading in our bedroom. A couple of hours from now, after everyone else in our house has gone to bed and been tucked in, I’m going to put in my earbuds and load the dishwasher and scrub the counter and return to bed by, oh, 3 a.m. Before bed and then after bed I’ll be corresponding, via email and Twitter DMs and open messages and Discord and Slack, with the people outside our house who buoy me up and mirror my worst moods and then explain or solve or ameliorate them, the people—some of them exactly my age, others not quite out of their twenties—whom I’ve found since coming out as trans, since announcing social and medical transition, since telling anybody who would listen that I’m a girl, that I have always wanted to be a girl, that I see myself in an achingly direct way not only in some of the poems of W. B. Yeats and Walt Whitman and Elizabeth Bishop and in Shakespeare’s Celia and in Mrs Dalloway but also in Rachel Gold’s Emily and Rachel Hartman’s Seraphina and the Pirate Red Queen Katherine Pryde, and in the articulate, close-knit, sometimes needy fan communities around them.

I have a community now. And I have more and closer friends, and they’re from more places, with a wider range of ages and backgrounds, than the friends I had before I came out. Some of my best friends are poetry people, just like they were when I started to try to write books, but at least as many are X-Men fans. Some of us—OK, six of us (R and Z and E and A and V and me), but we’re trying to make it catch on—have a semi-private term for the help established trans adults can give young trans people, especially those met through fandom. We call it wolverining, after the kinds of help that Logan, the older of the two X-Men named Wolverine, gives the younger one, and gives teen mutants more generally. You can wolverine any young or needy trans person, but only some such people are eggs. (The older and far more broadly used term egg refers to trans women, or girls, who are just now realizing they’re trans.) I was once an egg; my friends and I build incubators together for the safe hatching of fragile ones. I have my people, and I see them, and they see me, even if it’s only online.

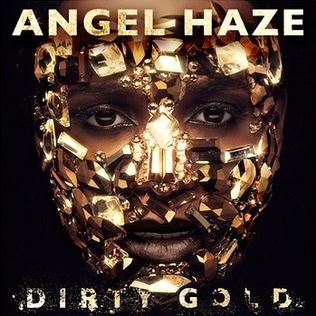

I also have my music, and it’s music I wouldn’t have discovered before. It’s music I found through my new friends, and some of it is by Angel Haze, a rapper, singer, and all-around musician who came up in the 2010s. Angel Haze is pansexual and agender and takes the pronouns she and her. In 2018 she began to release new music as Roes, an abbreviated version of her birth name, though her best-known work and her social media handles retain the earlier chosen name. A good place to start—the first song a dear friend who’s good at wolverining threw at me—is “Angels & Airwaves,” a hip-hop–pop hybrid openly addressed to lonely queer and trans people, people in danger, especially people younger than me. “If you’re contemplating suicide this is for you / See this is for the moments you alone with emotion/ So fucking bold leaves you mentally frozen…”

There’s no subtlety in this at all. There can’t be. Not in the commandingly bold hip-hop verses, nor in the anthemic chorus: “I’ve been running all my life / And I need you to stay, I need you to stay.” That final long a stretches out like a climber’s tether, a timeline, a lifeline, leading back to the post-chorus invitation where Angel says her words are a shelter, a safe place to hide, as well as a trail of breadcrumbs if you need them: “Put your headphones on, put your headphones on…” It’s specific about reaching people in danger, and equally specific about its outreach to people of many backgrounds and many genders trying to fend off the hooks of the patriarchy: “when the girl that you love won’t look in your direction / when the guy you like adds you to his fucking collection…”

It’s a song made to be shared, a song that knows how teenage self-importance is really a form of self-protection and adults are too often just numb to the damage. And it’s a song that says—in English, and in a way backwards—what’s said on all those millennia-old tombs. Classical inscriptions say “remember that as I am now, so shall you be, for I was once as you are now.” What they mean is you’ll die someday; nothing matters that much; expect less. But what Angel means is I was there; stay alive, ’cause you’ll join me here, and I need you. Expect the world.

And Angel has absolutely been there. Even the most privileged kids, like me, can find something to hear in her big sound, but she’s been through a lot more than most, and her life has been frankly nothing like mine (you can look it up). Out of earlier isolation and pain she’s made a tool for communities—and a song about how songs work, about radio, and about all the other kinds of long-distance community stretching across time and space, for which radio’s airwaves give us a modern metaphor.

*

Twenty-five years ago I was in another kind of enclosed space: a radio studio, with two turntables, two CD decks, two reel-to-reel players, and room for two or three people. There was one Plexiglas window—covered with Post-It notes, paper schedules, and reminders—looking out on a record library, any source of sunlight at least three rooms away. Not that the distance from the sun mattered much: I was there at night, sometimes all night, doing my best impression of an on-air expert in all things indie rock and supervising other college students who were pretending to do the same. We were a real community coming to you, wherever you were in the greater Boston area, over the airwaves at WHRB 95.3 FM, bringing you obscure, antisocial, or low-budget punk, post-punk, rock, pop, and so on from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. each weekday night, and I loved it more than words can say.

When I did a radio show, or planned one (rule of thumb: two hours of planning for one hour of good air), I could be one of those angels on the airwaves; I could bring the music to people who never had to see me. I could be a teacher and a prize student, offering up expertise to people who chose to be there, in their cars, late at night, or maybe under covers in their bedrooms, people who would never give me a grade, though when they called in with a thank you or a request it felt a lot like getting an A.

I loved it because I got to discover good music that almost nobody else knew about, or at least that’s how it felt. I got to accumulate subcultural capital, to feel cool, according to certain nerdy metrics of cool. And I could do it all where nobody had to see me, where it didn’t matter how I looked, where I had a great rock and roll excuse for not wanting to go out on Saturday night, not wanting to dance, not wanting to date in any way that looked like dating to the outside world. These are definite assets if you like your life but hate your body, if you’re happy in friendships but baffled by romance, if you’re trans and you don’t know it and nobody’s telling you because it’s 1992. Better to stay in a basement and spin more tunes.

Better still if some of your favorite tunes describe your life, the good parts (when I started dating someone I ended a show with Big Star’s “I’m in Love with a Girl”) and the absurdly appropriate parts (“Someone Else’s Clothes” by Ultravox and “When You Were Mine” by Prince: the trans girl new wave), and the parts that were just too right for words, and so obscure that no one else would play them. Did anyone know my radio shows were shaped around my own so-deep, so-sad feelings? Probably not. That was another reason I did them. They let me present those feelings in a code no one bothered to break.

The Lines were a crisp, melodic, minimal, very English post-punk act—think Wire’s Chairs Missing or R.E.M.’s first singles—whose reedy songwriter-guitarist, Rico Conning, found later success as a producer and sound-design guru. Conning’s singing sounded achy, awkward, slightly nasal, anti-macho, uncomfortable with the real world, unlikely to enjoy a night on the town but unlikely to calm down enough to stay in. My favorite Lines song was, and is, “Not Through Windows,” an ultra-catchy deep cut from an EP so hard to find that our library didn’t own it. “I want to see for myself / But not through windows,” Conning intones. “I never hoped for anything / Except for what there was.” His vocal melody leaps up and then falls back, disappointed, over a bass line that just keeps chugging along, like a commuter train rushing right past your stop.

Conning was singing about feeling stuck indoors, like a DJ in a studio, about looking for a real life that never quite came, about an uplifting, crowd-unifying scene and music that he—like most of his great white English post-punk compatriots—would never be able to make, though he knew, his song knew, that somewhere it could be made. Had been made, while he stayed home.

The Lines were looking inward, paring rock music down to its slightest elements as Wire had before them, playing a song you could dance to, or rather sway along to, on your own, in your English bedsit or your US dorm or your college radio studio. They didn’t expect an answer. They didn’t get one. Angel Haze, singing with far more drama about another kind of loneliness—or is it the same kind?—mixes up hip-hop and diva vocals and slow burns and insistent accelerations, static and clarity, aural collage that fills up your earphones and any empty space left open for her listeners. She knows there are angels on the airwaves because she’s heard them; now she’s singing back to you.

Twenty-five years ago I could have gone out but I stayed in; I knew what I liked but what I liked was homogenous, and I didn’t know where I belonged. Now I can’t go anywhere, literally, because it’s early May 2020 and you know the drill. But I feel like I’ve joined a party. I’m calling out to people I care about because they resemble me—in newsgroups, in published work, in chats online—and those people sometimes call back. We take care of one another, from far away. We are heterogeneous, at least a bit (not all of us are white! not all of us are good at school!) and we have somebody to tell if something goes wrong, or right.

I still like the Lines. But I like Angel Haze more.

— Stephanie Burt

Belmont, MA day 54