It’s incredible to think of what I didn’t know then. On the first day of college, I asked a black man from Brooklyn to Harlem Shake for me. In 2005. You’re from Maine? people kept saying, underlined and italicized. I was almost afraid to speak, for fear of what new ignorance I might reveal. All through my teenage years I had been trapped in cycles of Wilco and Modest Mouse, Parliament and Oscar Peterson; I was not prepared for Atlanta at the dawn of snap music.

D4L’s “Shake Dat Laffy Taffy” was the first of those songs I remember. It sounded like it had been made on a Casio keyboard, two index fingers jabbing out a two-note beat. My roommate, who didn’t say it but really wanted me to know she was blacker than me, insisted that the dance we had all started doing—a three-beat shuffle, a ti-ti-ta, ti-ti-ta—was not called the Laffy Taffy, just set to a song by the same name. My mother lamented that my generation would have no true music to look back upon, as if George Clinton weren’t famous for singing about a flashlight.

But even amongst ourselves, debate raged—were these songs dumb? There were so many of them—“Snap Yo Fingers,” “Wait (The Whisper Song),” “Knuck if You Buck,” “Oh I Think They Like Me,” and, as I recall, both “Ho Sit Down” and “Do Your Dance on That Ho.” They certainly were misogynistic. I was at the women’s college whose students had once vanquished tip-drilling Nelly from campus during his own bone marrow drive! The problem was that, though the songs were about nothing more than women and clubbing and money, they were catchy. My mother had the mashed potato, the popcorn, the jerk. Our dance was made of candy.

I spent the fall of my junior year taking classes in New York, hanging out with all the black people who wanted to be hung out with. Columbia parties were different—they were in the dorms, and often got shut down by campus police. They played a lot of Swizz Beatz. They sometimes had DJs but the Southern music they played was… delayed. This was 2007. The internet was ripe but Twitterless. Facebook was still just for us. Talking to strangers, sharing unfounded opinions, wasn’t as simple as it is now. If Soulja Boy released a song, it took some time to swim upstream from Atlanta. That’s what I noticed that semester: New York was just now hearing songs I had heard six months earlier.

But there were whole tracks, whole branches of the genre, that didn’t make it out of the A. How I loved the Jumprope Boys, and that song (with accompanying dance) “Jump the Rope.” Who were those young men? (When I asked someone what had happened to them, all I was told was that they were “Brittny’s friends.”) Or “Check My Footwork” a DC-adjacent, feet-beating track that got quickly remixed into “Check My Facebook”: “Ye ain’t friend me, Ye ain’t poke me / Stop looking at my pic ’cause Ye ain’t know me.” What happened to those songs?

Last year I found myself wondering about one such song. I posted an appeal to Instagram, asking for help identifying something by Young Jeezy. Like so many Jeezy songs, it was defined by his signature “Chea!” adlib. It was a slow, melodic, Southern groove. But all I could remember was the beat’s duhn duhn duhn duhn… duhn duhn duhn duhn and the lyrics’ “Big___, big____, big something-something.” Impossible to Google. According to my DMs, perhaps it was “Dey Know” by Shawty Lo? It was not.

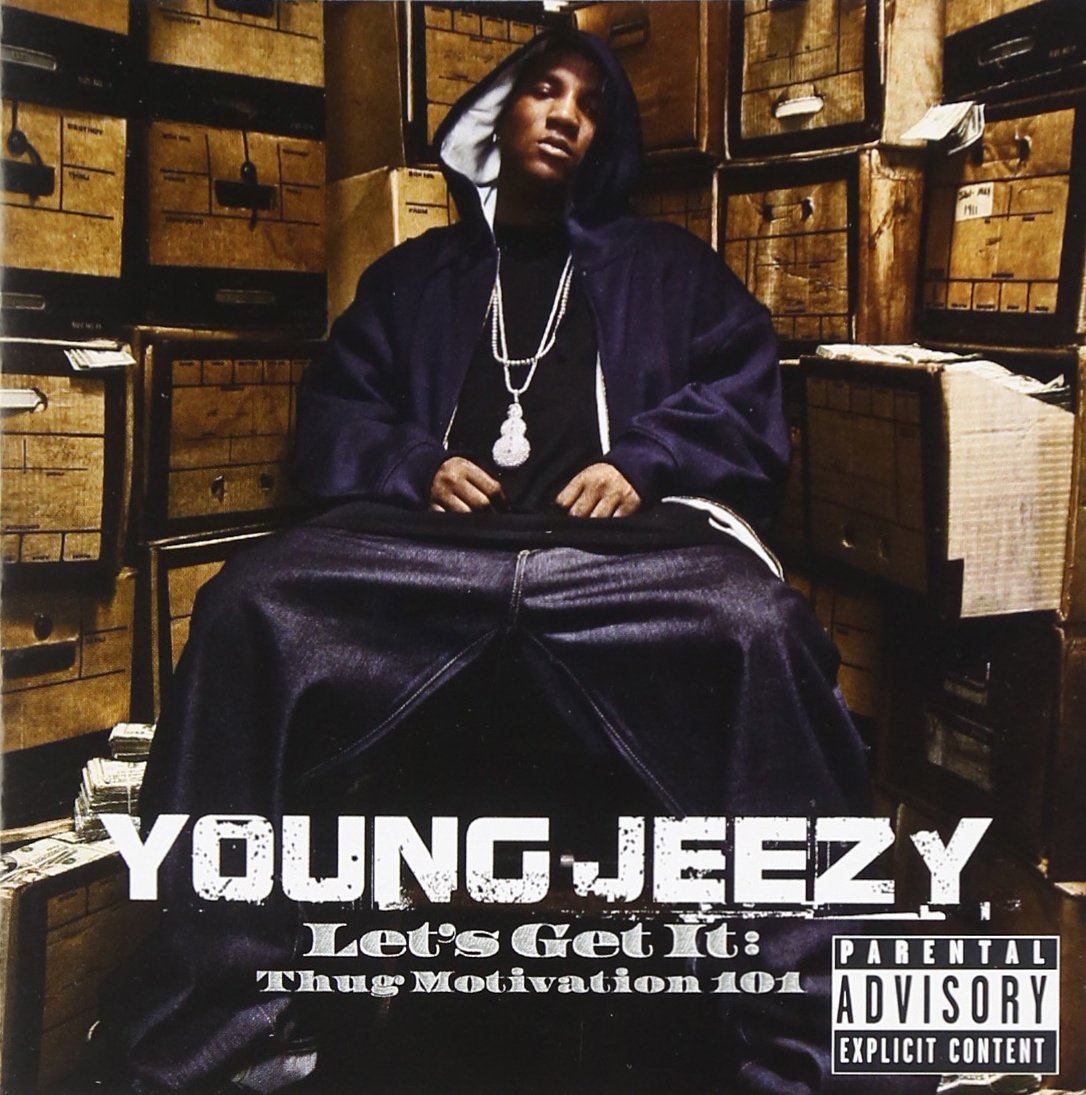

Then came Corona. Then came a certain wistfulness for the man I didn’t marry, who had moved to Atlanta. Then came time. And Wikipedia. A careful scouring of Jeezy’s discography, including his features, then a methodical search of the streamers. A-ha. I had found it—but not before a revisit to Let’s Get It: Thug Motivation 101. This was Young Jay Jenkins’s major label debut, July 2005, when I was still in Maine and my mother and I were doing the ultimate back-to-school shopping as I prepared to start college at her alma mater.

These were the songs from my earliest adulthood. “And Then What,” whose refrain I had been unwittingly singing back to people all these years: (“First, we’re going to the museum.” “And then what?”). There was “Trap Star.” There was “Bang” (muthafucka, bang!) and “Soul Survivor” featuring thee Akon. How many times had I dreamed of being at a fancy event, on stage at soundcheck, letting out that clarion call “Akon and Young Jeezaaay”? It had been a while, but I remembered these songs. I remembered them as songs I never intentionally listened to—they just were, like air and pollen. They were on tinny laptop speakers and in restaurants and at BBQs and in the cars of dudes who drove around campus and didn’t even pretend to go here.

These were our gravelly anthems. And they were songs that, unlike anything by Drake or Usher or Lil Wayne, didn’t completely escape the pocket of time in which they originated. I know because I hadn’t heard them at nan club, bar, or house party since. Maybe I’m not the best judge. How many of those places do I frequent? How many did I frequent back then? I don’t know. Enough to know what it’s like to finally be out, reveling in the pleasure of hearing a beloved song for the first time in fifteen years. A song you loved, that we all loved together, but that wasn’t a single, wasn’t a radio hit, didn’t make it up the coast.

I’m sure I could have found the mystery song sooner than I did. But I let it linger in that liminal space between memory and recall, that place zapped nearly to death by the pervasiveness of the internet. My age is somewhere between having had all these technologies at my fingertips since the dawn of my adulthood and needing to remind myself to never again call something crunk. For as long as I could, I chose to savor the pleasure of an unanswerable question—an image that disappears as soon as you open your eyes.

Whenever I want to remember those days now, I put on a homemade playlist called “Fresh Woman” and, in a moment, I’m back on the yard where we all crouched down, rose up saying Awwwwwww… Boo! on the beat drop—something I thought people did everywhere, something I tried to bring to New York but which turned out to be, like so many things, specific to a place, to a time, to the people in the room.

— Kyla Marshell

Brooklyn, day 88