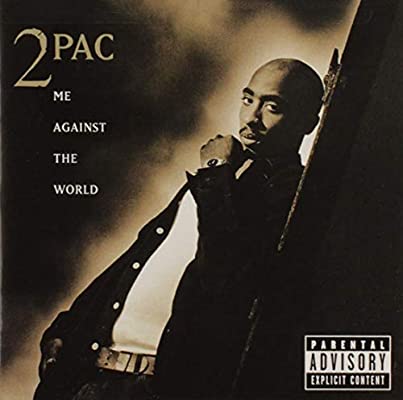

In 1996, you couldn’t walk two blocks in Morningside Heights without hearing rap or hip-hop. It was the heyday of Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, the summer of “California Love.” Of the three CDs I owned—along with Mariah Carey’s Daydream and TLC’s CrazySexyCool—my favorite was 2Pac’s Me Against the World. I listened to it on repeat when I was alone; something about the syncopation of the rhymes and the density of the lyrics helped anchor me to the ground.

I spent a lot of time transiting alone from one place to another that year, in buses or in cars or on foot. I attended two schools: one for the “gifted and talented” and, on Wednesday nights and all day on Saturdays, a program downtown that helped marginalized students secure scholarships to private schools. Most days after school that fall, I would stop at the bodega for an Arizona Iced Tea, turn the volume up high on my Discman, and make the uphill walk home to begin a night of homework.

At first, the music was mostly about blocking out the catcalls from men on the streets who did know, or did not care, that I was twelve. Those cheap foamy headphones were a sonic shield, and I needed it: that was the year I would get my first period and learn the new shame of walking home with a borrowed sweatshirt tied around my waist. I was pinballing between different kinds of overwhelm: the chaos at home (my exasperated mother chasing my bawling toddler sisters up and down the halls of our apartment), my workload (I seemed to be bombing math in both schools), my social life (or lack of time for one).

I didn’t know much about Tupac Shakur besides what I heard on the radio. I wasn’t interested in his life story or the East Coast/West Coast rap rivalry; I didn’t even know the rest of his discography. All I knew was his youth, good looks, and insouciant braggadocio. As an awkward, unsure pubescent girl, I envied that confidence, which seemed to be the birthright of boys. But infused in those verses, too, was a sweetness, an earnestness, a desire to be understood. And so in the little time that was my own, I gave myself over to the pure pleasure of playing Me Against the World on repeat, the syncing of footsteps to beat, the green reverence for the verse.

When Tupac was gunned down in Las Vegas that September, I couldn’t wrap my mind around it, even though I lived in a neighborhood plagued by gun violence too. In fact, it seemed everyone else in New York was in the same shock that fall, heads bowed low at the radio. On Hot 97, the DJs talked incessantly about the shooting between replays of 2Pac songs.

When I was growing up, we spoke only Spanish in my house. (We still do.) That year I rarely spoke at home, beset as I was by anxiety. But when I told my parents about Tupac on a drive to BJ’s Wholesale Club, my sisters quieted down in their car seats. I was talking a lot, which was rare, and I was talking about death. My parents, immigrants from the Dominican Republic and Cuba, asked a lot of questions. How could a flashy music star fall prey to the horrors they themselves had come to America escape? They started letting me play Hot 97 on family car rides. Through my updates and translations, we all followed the drama that culminated in Biggie’s fatal shooting the following spring.

By sixth grade, I must have read poetry in school, but I don’t remember it. My first memory of English-language poetry is rap. It’s 2Pac. I read The Odyssey that year, but telling my family about Tupac, and translating into Spanish his significance, his talent—that was my first experience of storytelling, of mythmaking. Who could have known it then? Tupac made me a writer.

Is it Joan Didion who writes about staying in touch with the person you used to be? The years have flowed like water between my fingers. Now I live in a sleepy suburb of DC and have spent much of the past two decades living and working overseas. My partner is stranded in Russia for the duration of the shutdown. My parents and sisters are still in New York. On the phone, they describe the parks and churches turned to clinics, the round-the-block lines for testing. Alone in self-isolation, I am writing a book in frantic fits and starts. The air conditioner broke this week, in the middle of a heatwave. My dog lies on the bathroom floor, desperate for coolness.

I’ve mostly avoided listening to Me Against the World since 1997—avoided that lonely, scared kid, the weight of a too-full backpack on her shoulders, trudging up Broadway with her headphones on, Discman blasting. But it’s as easy as a couple clicks on Spotify. I’m there again. I know that girl.

— Yohanca Delgado

Bethesda, day 136