I’m an English teacher, and like many other off-white-collar professionals, I experience fear and loathing every Sunday night. No matter how relaxing the weekend was, my computer gnaws at the good vibes as I respond to emails and plan lessons and psych myself up for five more days of convincing people that words matter. I’m grateful for my calling, but that late-night scramble is as inevitable as it is depressing.

Honestly, the only time in my life I ever felt free on a Sunday was when I spent a year between college and grad school selling CDs at the mall. (In fact, Monday was usually my day off at F.Y.E.) My shift might look like this: open the store with one other coworker—sometimes Tiffany, who got ridiculed for carrying hand sanitizer. Organize new and used products, the best of which I might set aside for myself. Point people toward CDs and DVDs I genuinely thought they would like. Take lunch at Subway, where everybody knew my name. Continue to ring people up and answer questions about half-remembered album art. Be the master of my domain and remind people they could save 20 percent by registering for a rewards card.

I didn’t make much money, but the hours flew by as I bounced around in all-black Air Force Ones, eager to talk and, yes, teach about the silly things I loved. We were two years away from carrying the internet in our pockets, so being able to name a song from half a bar of humming had real value, maybe for the last time ever. Nothing brought me more joy than when an overmatched coworker called me over to bail him out with a customer. If that doesn’t sound like the ivory-tower gaze of a budding teacher, then I don’t know what does.

Sure, there were minor frustrations, like the constant mandates to push magazine subscriptions or ESPN cellphones. Some devious customers might peel a $9.99 sticker over a $15.99 sticker and feign surprise when Akon rang up at his actual price. We employees also had to numb ourselves to the same company-curated compilations for a month at a time. (I dare you to listen to Trace Adkins’s “Swing” four times a day for a month, then return to this paragraph and see if you still know how to read.)

But unlike today, when my inbox count rises as I sleep, I had no responsibilities when I took off my nametag. I doubt my bosses even knew my landline number. After clocking out, I went home to the second floor of my mother’s house to chomp on gummy worms, watch late-night NBA, and blog about whatever rap music had come out that day.

At the time, “whatever rap music had come out that day” probably involved Lil Wayne, a fellow New Orleanian whose dizzying recording schedule yielded over a hundred songs in 2007. Some of them were official features for performers as disparate as Lloyd and Enrique Iglesias, but most of them were debatably improvised tangents over the instrumentals of popular songs, compiled and slapped onto free, self-released mixtapes.

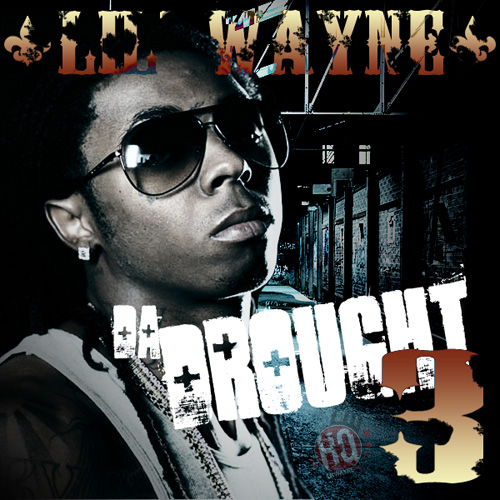

Yet these weren’t the leftovers we had come to expect from the mixtape medium: this music was undeniably his best work. Wayne hurdled over whatever expectations even he had built when he dropped the “viscerally satisfying” Da Drought 3, the mixtape equivalent of Sgt. Pepper’s but with more drugs. This “idiosyncratic blast of sunshine” was “confident in attitude but warbly in delivery.” “Weezy [strung] together imaginative, hilarious couplets that not only [justified] the mixtape’s running time but [left] the listener wanting more.” “His buoyant flow and singular croak [expanded] over the bass-heavy selections, which [were arranged] in delicate sequence.”

I’m quoting myself there. There was plenty more giddy mythologizing where that came from. For example, I spent a whole paragraph decoding an allusion to an early-’90s Rosenberg’s Furniture ad that ran during Saturday morning cartoons—just one obsessive rant on a blog that covered Chris Paul free agency rumors, camera movements in crime movies, the #32 album of the decade, and a one-act play about Brett Favre. With trial-and-error HTML and a surfeit of Miller High Life, I wrote until I couldn’t keep my eyes open. Reviews and lists bled from my fingers. More than once I woke up my mom because I was making myself laugh so hard.

I wish I could still produce like that. I pretended that someone was holding me to thousands of words a week, that out there was an ideal reader cracking up at my references. I pretended that a societal good was achieved by my assessment of the metaphor “yellow-white diamonds, call it cheese on them grits.” And presentation was just as important as content: I cared so much about uploading MP3s for my readers that only elusive “CD-quality” files satisfied me. If Web 2.0 proved anything, it’s that it took a lot of work to have fun.

Like most other people writing for the internet at the time, I lied to myself about my rabid audience. For the purity of the delusion, I didn’t track visitors with analytics, and I didn’t reach out to the satellite of bloggers I considered, in a new and difficult-to-define way, friends. No, despite the effort at my computer, I wasn’t trying to translate my writing into a career. (I probably wouldn’t have borrowed dozens of thousands of dollars for a teaching degree months later had that been the case.) I just felt a desperate creative pull, one I haven’t been able to rebottle since. In fact, like Lil Wayne, I found some transgressive appeal in scratching the inside of my brain and pouring it out for no monetary gain. I was on autopilot for my actual livelihood, and the savings went toward creating this product that may as well have existed for only me.

Now that I am a busier but less creative man, I remember that frivolous lifestyle fondly. The superficiality might be why I was so attracted to music that was purely virtuosic in the first place. Wayne wasn’t trying to weave a narrative or build cohesive themes or touch your heart. He just wanted you to laugh at “yellow diamond ring lookin’ like a little Funyun” or marvel at his ability to stitch a whole verse together with the same double rhyme. Is it true that all he rapped about was women and drugs and status? Maybe so. But he had ways of bragging about those things that no one else had thought of. And in my best moments I had ways of bragging about him that no one else had thought of.

Even then, retail, the music industry, and the music retail industry were dying. The Wendy’s in the food court was holding on, but the Sbarro had been converted to a Papa Something’s. My coworkers sneered at the people we called scribes, who were just writing lists of albums they would go home and download illegally. But customers could just as easily turn their noses up at us: after all, we didn’t sell Da Drought 3. No matter what kind of credibility he had among rap listeners, no matter how many people could quote “You don’t want to crash like La La La Bamba,” Wayne was strictly gray market. We could not sell the best music, the music people were begging to buy, and that’s why F.Y.E. turned into a gym, which turned into a bounce castle, which turned into a cell in a Coronavirus-stalled complex that will probably never reopen.

When I got serious about teaching, I wrote a post called “Nothing Left to Say” and deleted my website. I had to protect myself professionally, and my opinions about Thaddeus Young’s readiness for the pros were irrelevant by then. Of course, I’m being precious about the intentions behind the work, but maybe you had to be there, or maybe the final product wasn’t as profound as I thought. In the abstract, of course I became a better writer by practicing with all my spare time. But this, right here, is all I have to show for it.

Around the same time of the big deletion, Lil Wayne released the long-awaited studio full-length Tha Carter III. His fans, fueled by fond memories of his apex, pretended it was a classic and made it the best-selling album of 2008. Really, though, expensive production carried a record on which the star sounded lost, oversexed and woozy. His figurative language was neither as compact nor as cogent as it once was. Even its strangest contrivances—“Dr. Carter” centers on how he might “operate” on ailing rappers to save them, and “Mrs. Officer” is a ballad to a sexy cop—have none of the serendipitous joy of even the throwaway lines on Da Drought 3.

A wise musician from my city told me once, “One life to live: never ask for a mulligan.” I don’t regret turning my attention away from double-checking links on a dead-end Blogspot account if it means I’m able to educate my students, love my wife, or raise my children. But in the same way Wayne was born to dribble non sequiturs and drawl double entendres, maybe those late nights spent bobbing my head along to tinny computer speakers were me at my truest self.

We all dust off our favorite records and interact with them differently as adults. For specific reasons, though, I almost never return to Da Drought 3. It’s not on streaming platforms, and I lost the CD when I… intentionally threw away all my CDs. Once a month or so I’ll remember a line but not the song it’s from, and I’m forced to sit with that tiny indignity in a world that supposedly has all the answers at my fingertips. More than any other piece of media, that music persists in my memory, just beyond my grasp, unable to convert to new ways of living, no more or less real than the name of the Smoothie King manager I used to flirt with. What was once the most important thing in the world to me is now just a thing I remember as important. But maybe that isn’t as profound as I think either. Maybe it’s just aging.

— Christopher Bowes

New Orleans, day 110